Touring the West Point campus under the drizzling, early-winter rain during my ten-year reunion, I was struck by the passage of time. It felt like yesterday that the class of 2013, shivering under spring showers, tossed our covers into the air in Michie Stadium, jubilantly anticipating our follow-on service throughout the world. And indeed, not long after that day I found myself leading an infantry platoon in Iraq. Then, before I knew it I was pinning captain, deploying to Europe, writing my first MWI article, commanding an infantry company, and making a leap into the foreign area officer career field. Ten years passed, all seemingly in the blink of an eye. As I transition from company-grade to field-grade officer, I would like to share some lessons I learned in those ten years to help current and future company-grade leaders find their versions of success and personal satisfaction throughout their careers as military professionals. I offer this from the perspective of officership but hope that these insights can broadly apply to service members of all stripes. From a decade of opportunities, successes, struggles, and camaraderie I offer ten pieces of advice.

1. Put first things first.

As a newly commissioned officer, it can be tempting to focus on future, highly selective opportunities ahead of the more mundane and immediate. As a young lieutenant, a member of my IBOLC (infantry basic officer leaders course) class eagerly asked an instructor what we needed to do as infantry officers to best set ourselves up for a career in Special Forces. “Triumph at IBOLC and graduate,” replied the instructor. His response, while not likely what most of us expected (or wanted) to hear, was exactly what we needed. It highlighted the fact that the gateway to special opportunities begins with excellence in the basics. If you are initially assigned to serve on staff before platoon leadership or company command, focus on being a great staff officer. You will benefit tremendously from understanding how your higher headquarters operates. You will build relationships of trust and respect with your commander and other experienced officers, noncommissioned officers, and soldiers who will be critical in supporting your future platoon or company’s success. Strive to be the best officer you can be where you are now and seize the next opportunity when it arrives.

2. Get your systems in order.

As a new platoon leader or company commander, there will be no shortage of events that seemingly require your immediate attention. Perhaps you arrive to your office determined to write your unit operation order for an upcoming training exercise. You turn on your computer and open last year’s order to use as a template—so far so good. Then emails begin trickling into your inbox. Motivated squad leaders stop by your office. Your cell phone is ringing—it’s the boss (again). Before you know it, it’s meeting time at the battalion. You look at your watch, the day’s hours are running out, and you haven’t changed a word from last year’s training order. Where did the day go?

Time management is one of the most challenging yet important skills for a new leader to develop. This is where developing a battle rhythm can help. This document provides a predictable series of operations, key meetings, and events tracked at daily, weekly, and monthly frequencies. Battle rhythms inform subordinate leaders of expectations during physical readiness training, command maintenance, training meetings, and other key events—to include dedicated time for troop-leading procedures and the military decision-making process. Leaders should ensure that important cyclical events of higher headquarters are reflected in their own battle rhythm so their unit actions are properly aligned. Of course, surprises occur and Murphy will always take his share of the day. However, establishing and enforcing a battle rhythm will help to create order from chaos and much-needed predictability for both you and your subordinate leaders.

3. Delegate and do your part.

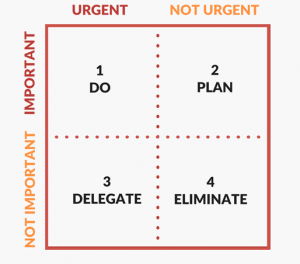

Now that you’ve managed your time, how are you managing tasks? There are several techniques, but I believe that all leaders can benefit from the Eisenhower matrix. When a task arrives, ask yourself whether it is truly important, and if it requires urgency or not. This should clue you in to whether you should either immediately do the task yourself, plan to accomplish it, delegate it, or eliminate it entirely. For tasks that are important but not urgent, for example, once you’ve conducted your initial planning you can delegate it to a subordinate by giving clear guidance. As a commander, this approach enabled me to focus on items that centered on my duties. This included training week management, short- and long-range training calendar updates, troop-leading procedures, and corresponding with my higher headquarters. As a battalion assistant operations officer, this enabled me to complete essential planning efforts and liaise with both brigade and company elements. To be sure, there are many factors that shape how you will conduct task management, to include the experience, talent, and preferences of your subordinates. Adjust your approach as the mission and circumstances require, and you will be able to manage your tasks and not let your tasks manage you.

4. Have the hard conversation.

Another critical challenge for officers, especially new lieutenants, is assessing the competence and character of their noncommissioned officer counterparts. From my experience, the vast majority are outstanding leaders who are experts in their craft. Personally, I owe my success in platoon and company leadership time to these phenomenal soldiers. That said, over my ten years I’ve seen a small handful of peers who had difficult relationships with their noncommissioned officer counterparts due to issues of character or competence. The most important thing new officers can do in recognizing and alleviating this problem is to ensure that they are of high character and competence themselves. If you know what right looks like, it’s easier to spot it (or its absence) elsewhere. Secondly, seek out other senior noncommissioned officers and officers that you trust to discuss your observations and to receive professional feedback. Perhaps it’s just a personality clash that will ease over time. But perhaps it’s something more. While initiating the conversation can be particularly difficult, early, candid, and professional dialogue is key to salvaging success from potential disaster. You owe it to him or her, your soldiers, and yourself to ensure your unit is one of high competence and strong character.

5. Write about your thoughts and experiences.

“The palest ink is better than the best memory.” The Chinese proverb reminds us of the imperative behind writing down our experiences—for yourself and those that follow in your footsteps. Whether you just finished a tour in command or staff, your successor will be very grateful for your notes and reflections upon your experience. Where did you succeed? Where could you have improved? What surprised you? Who, or what, were the key resources to your success? Answering a few questions like these is a great way to provide helpful guideposts to your successors as they navigate the journey you just completed. Never doubt the value of your experience or the ability of your writing to positively affect other service members. With renewed senior Army leader emphasis and grassroot efforts such as the Harding Project, there has rarely been a better time to write for the profession. I have had the opportunity to write about my experiences as a staff officer, as a company commander, and as a liaison officer, and I hope those articles were as useful to others preparing for those roles as they were in helping me to identify and reflect on the lessons I learned during each.

6. Tackle your weaknesses.

I have a confession to make. Remember the infantry lieutenant too eager to join Special Forces? It was me. I was too focused on what kind of workout would best prepare me for Special Forces selection to be bothered with mastering the infantry basics. Sure, I graduated and knew how to brief an operation order—but I was still struggling to properly lead an infantry patrol. Don’t take my word for it, though. Ask the Ranger School commander who kicked me out of Darby Phase on my first attempt. It was a really rough day, but I had no time to feel sorry for myself. I had to figure out how to improve my patrolling competence and confidence—fast. I had one month before the next class and the stakes couldn’t have been higher. An officer from my follow-on unit informed me that no tab meant no platoon. And no platoon meant no deployment. I printed off all the ranger patrol cards, laminated them, and reviewed them everywhere I went for the next month. I mentally rehearsed my actions on contact, leader’s reconnaissance, and actions on the objective until I knew that I could pass all graded patrols in Ranger School. And thanks to those efforts in tackling my weaknesses (and thanks to my Ranger buddies), I passed—but I did it the hard way.

7. Take care of those who take care of you.

As a new army leader, you will likely find both challenges and opportunities spread across some good days, some tough ones, and everything in between. You may be surprised, though, at just how many people are invested in your success. From the soldiers in your platoon to your family at home, your peers, and senior officers, all have an interest in your professional success. Try finding out what they value and see if there’s any way you can give them a token of your appreciation. Perhaps your soldiers really value their time (who doesn’t?). When you anticipate a hard week of training, plan an appropriate period of down time once recovery operations are complete. Be sure to brief your boss at your training meeting. He or she will likely approve, commending your desire to reward hard work and your ability to forecast this in advance. Be sure to say thank you to the peers who got you out of a hot situation (on multiple occasions). Call home and thank the ones who are supporting you on this journey. Send them the photos you’ve been taking and you will likely make their day.

8. Foster a culture of cooperation.

I have one last confession. The company battle rhythm I previously mentioned wasn’t my idea. I adopted it from a fellow commander who was achieving great success through his organizational skills. In the initial weeks of my command, I was dousing daily (or hourly) fires while he was reserving land and ammunition months in advance. Touring his office one day, I noticed his battle rhythm product, and suddenly his organizational dominance all made sense. He deliberately set aside one afternoon a week to complete troop-leading procedures for the various operations his company was conducting. Knowing how much I could benefit from his system, I asked for his product and adjusted my processes accordingly—ultimately to the benefit of my soldiers and leaders.

Another peer had an excellent company maintenance system. From fault to fix, he had a detailed system for tracking broken vehicles, ordering parts, and ensuring their expedited repair. He invited me and my executive officer to observe his weekly maintenance meetings. From this opportunity we adjusted our processes, which resulted in greater predictability, more efficiency, and ultimately a higher level of operational readiness. And of course, I shared my own innovations as well.

Perhaps the most important takeaway is how much more effective and enjoyable it was to work in an environment of cooperation. Everyone had each other’s backs and was eager to help. Of course, we were always highly competitive (and sometimes cutthroat) when it came to certain events like battalion physical training competitions. But in terms of collective readiness, we were always willing to help out our peers to our left or right. Among company commanders, no one was unwilling to give out a product or share advice, afraid that a peer’s success would negatively affect his or her own evaluation. In a matter of just eighteen months, my brother and sister commanders became some of my best friends. As we each passed down our guidon, we were all able to celebrate a successful journey together as company-grade officers with amazing follow-on opportunities, the privilege to promote to field-grade ranks, and unforgettable memories together.

9. Have an open mind.

When one door closes, be ready to open all the others. You may be all the happier for the outcome. Personally, I was a bit disappointed that after my career course I was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division at Fort Riley and not Fort Hood. I wasn’t too keen on the upcoming Atlantic Resolve deployment to Europe, and I definitely did not want to serve as a liaison in Lithuania away from the unit. And yet, I am infinitely grateful for each of those experiences. My time serving at the US embassy in Vilnius inspired me to compete for the foreign area officer program. My peers at Fort Riley became my best friends. I commanded an amazing company—filled with outstanding officers, noncommissioned officers, and soldiers. Of course, one could suggest that I was incredibly lucky. I would agree. But I would also say that keeping an open mind and doing the best I could went a long way toward finding that luck. When one door closes, be ready and willing to open the other.

10. Take photos.

I saved perhaps the easiest recommendation for last. When training conditions permit, take as many photos as possible—especially with the friends you make along your Army journey. The only photos I regret are the ones I didn’t take. Each photo tells a unique story of soldiers, colleagues, and experiences of a lifetime. My favorite feature is to scroll across a map of the globe and review the incredible places my Army journey has taken me. Through infantry training and parachute jumps at Fort Liberty to Bradley operations at Fort Riley and deployed experiences around the world, the photos are a reminder of how lucky I am to have had such amazing experiences, and to have met the best friends in the world. I’m really looking forward to capturing photos of what the next few years will bring, and I hope you are too.

Captain Harrison (Brandon) Morgan is a US Army foreign area officer for the Middle East and North Africa. As an infantry officer, he served in command and staff roles overseas in Iraq, Lithuania, and the Republic of Korea. He also served as an MWI nonresident fellow between 2019–2020 and 2021–2022.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Scott Fletcher, US Army National Guard