Maybe it was the thrill of the smoke-filled cave, leading a team of well-trained soldiers each carrying sixty pounds of oxygen tanks and wearing sweat-filled gas masks as they methodically cleared enemy forces from a mock chemical weapons bunker. Or perhaps it was the feeling of extraordinary accomplishment as our vehicles returned to our home-station motor pool after nine months of service overseas. It could have been fist bumping a newly promoted sergeant whose platoon leadership coached and mentored him to success. More likely it was a combination of all of these moments and many more that affirmed my belief that company command was the most challenging, rewarding, and demanding duty I have undertaken in my eight years of Army service.

Across the force, captains serve dutifully in critical staff positions in anticipation of the opportunity to take command of companies. The Army has a vested interest in their success, as their companies’ readiness depends on these officers’ leadership. From eighteen months as the commander of a Bradley mechanized infantry company, I offer these future company commanders four recommendations.

Prioritize Prioritization

As a company commander, prioritization of missions with effective resource and composite risk management is the foundation of all other duties and responsibilities. Commanders who understand, visualize, describe, and direct priorities through clear and concise communication enable leaders to allocate time, personnel, and equipment to accomplish their objectives efficiently. Conversely, commanders who fail to prioritize or clearly articulate often risk creating confusion, misdirection, and mission failure.

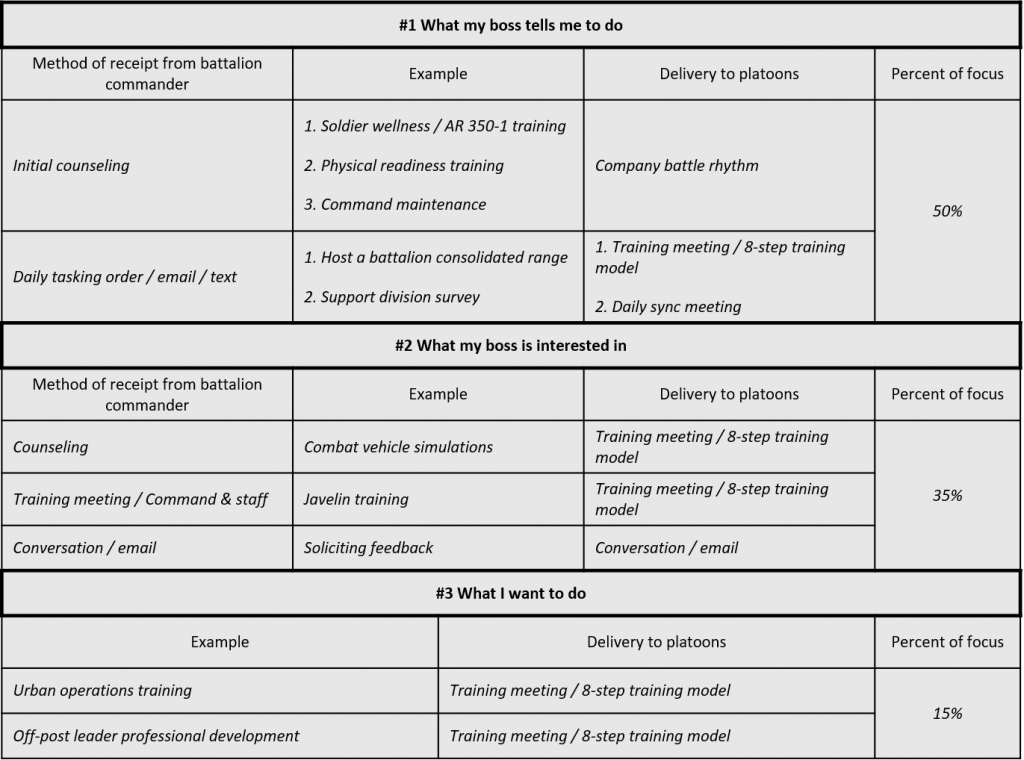

In my experience, I found that the best way to conceptualize my priorities was to think of three categories:

#1: What my boss tells me to do

#2: What my boss is interested in

#3: What I want to do

First and foremost, directives from the battalion commander or the institutional Army (e.g., Army Regulation 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development) always come first. Swift execution of command directives builds the foundation of trust required to lead organizations of a hundred-plus soldiers, dozens of combat vehicles, and millions of dollars in special equipment. Commanders’ directives are generally straightforward and easy to understand, whether communicated verbally or electronically.

Secondly, I was guided by a simple idea: what interests my boss fascinates me. While this is perhaps the most difficult priority to interpret and take action on, it is the most important for subordinate company commanders to understand. By discovering and executing their commanders’ interests, company commanders purchase time, maneuver space, and trust to further execute their own objectives. Typically, battalion commanders express their interests in initial counseling, verbal feedback during meetings, or within written communication. Personally, I recall during my initial counseling when my boss described his interest in focusing on companies conducting dismounted Javelin training. While I did not disagree with the importance of this training, it required a deliberate allocation of time that could have been spent on other important dismounted squad tasks, such as conducting offensive and defensive urban operations. However, by building a deliberate Javelin gunner train-up using the principles described in Training Circular 3-22.37, my battalion commander trusted our company with the time to train on other important dismounted tasks.

Finally, after accomplishing their commanders’ directives and interests, company commanders execute their own priority training objectives. This consists of training outside mandatory requirements of Training Circular 3-20.0, Integrated Weapons Training Strategy, Army Regulation 350-1, and other Army-wide regulations that fall into priority number one—what your higher headquarters mandates that you must do. For a company, this may include any follow-on squad or section tactical training that requires additional repetitions. For my company, we achieved success in traditional offensive and defensive operations, but required additional training in both movement to contact and consolidation and reorganization activities. By initially securing my higher headquarters trust in accomplishing their directives and interests, we earned the trust, time, and resources to execute a training exercise focused on movement to contact and reconsolidation activities.

Future company commanders may correctly note that this prioritization often leaves little or no room to execute their own training objectives—in my case this was mostly true. Company commanders in a traditional brigade combat team achieve their unit’s training objectives through disciplined execution of Army mandates and the imperatives of their higher headquarters. This focus allows company commanders to build well-trained, disciplined units ready for live-fire exercises, combat training center rotations, and global deployment. Efficiently accomplishing the first two categories of priorities is the best way to maximize time for the third. I have created the chart below to encapsulate my advice for how company commanders can conceptualize execution of priorities. It begins at receipt of directives or guidance from their commanders, continues through delivery to subordinate platoons, and concludes with my recommended share of focus for a company commander.

Establish Systems of Success

To achieve unit objectives in garrison and operational missions, new commanders should quickly establish their systems of success.

In garrison this includes a company battle rhythm, a short-range training calendar, and long-range training calendars. A company battle rhythm provides a predictable series of operations, key meetings, and events tracked at daily, weekly, and monthly frequencies. The document informs subordinate leaders and their expectations during physical readiness training, command maintenance, training meetings, and other key events. Company commanders should ensure that important battalion and brigade cyclical events are reflected in their own battle rhythm so the company’s actions are aligned to their higher headquarters. For example, during daily physical readiness training my company rotated platoons through the two mobile gyms Monday through Thursday, with Friday reserved for off-post training and competitions. We conducted Bradley vehicle maintenance weekly, every Monday. During the first week of the month, dismounted soldiers conducted weapons maintenance from the arms room, with the first platoon leader or platoon sergeant leading the effort and reporting the result and way forward at the close of business. We continued this cycle for each week of the month accordingly. This provided our leaders predictability and a degree of ownership in having well-maintained equipment.

Commanders use short-range training calendars to provide the “five W’s” for the next three training weeks. Color categorizing events by type (field training, maintenance, organizational health, etc.) and sharing the calendar with subordinates provides real-time situational awareness and predictability to platoon and squad leadership. Company commanders should include key end states for each day in their short-range training calendars to guide and assess mission accomplishment.

Company commanders use long-range training calendars to provide leaders and soldiers predictability out to six months into the future. These calendars must begin with higher headquarters operations, to include combat training center rotations, collective exercises, and block leave, among others key events. Company commanders should plan according to the 8-step training model and the PERL system—planning, execution, recovery, and leave—to ensure thorough planning, quality execution, and deliberate post-exercise recovery.

Build Your Team

Company commanders build their teams through a range of activities, including counseling their subordinate leaders, conducting leader professional development, and hosting squad-level competitions. These components provide leaders with expectations and enable constructive training, all while building unit pride and esprit de corps.

While commanders have the freedom to design their counseling within the guidance contained in Army Techniques Publication 6-22.1, The Counseling Process, commanders should consider framing their expectations in the context of the attributes and competencies described in Army Doctrine Publication 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession. Commanders describe what they expect their platoon leadership to “be”—in terms of moral and ethical character. They describe their expectations of what they should “know”—how they should apply judgment, innovation, and interpersonal tact in solving problems. Lastly, commanders describe their expectations for what their platoon leadership must “do”—lead by example, develop their subordinates, and achieve their commander’s enduring priorities.

New commanders, like new platoon leaders, will likely not have all the answers for what they expect from their platoon leadership. That is okay. What is important is for new commanders to establish a framework for continuous dialogue, constructive feedback, and ongoing leader development. New commanders should use their initial counseling to conduct an overview of their systems of success, expectations for enforcement at echelon, and how the company can enhance those systems over time. Informal counseling through constructive feedback during physical readiness training, preventative maintenance, battle rhythm meetings, and field training after-action reviews provides platoon leadership continuous opportunities to grow as Army leaders.

New commanders should build a leader professional development program focused on growing squad and section leaders as competent, capable leaders in both garrison and field training operations. In garrison, commanders should focus on how these leaders communicate with their soldiers, conduct counseling and corrective training, and fix issues identified by subordinates. In the field, commanders should design leader professional development that is grounded on squad tactical tasks that nest within platoon and company mission-essential tasks.

Finally, a new commander should consider hosting squad-level competitions, ideally monthly. Competitions, especially battle-focused physical readiness competitions, accomplish multiple objectives. First, they develop platoon leaders’ collaborative planning skills as they actively solicit feedback from their NCO leadership. Secondly, the battle-focused components hone soldiers’ and leaders’ tactical capabilities and expertise. Lastly, competitions build a sense of teamwork, unity, and esprit de corps throughout the company as squads actively compete for supremacy and bragging rights among their peers.

Support Your Fellow Commanders

Commanders, especially those new to the role, should focus on standing with their peers instead of standing apart. Collaboration, cooperation, and unity of effort are the watchwords and guiding principles in peer relations. When the battalion commander asks for recommendations on a course of action, company commanders should strive to come to a consensus and unified recommendation when time permits. When one commander has an idea to share with the battalion commander, he or she should share that plan with the battalion’s other company commanders, and ideally present a unified course-of-action proposal. Five or more company commanders “maneuvering” in the same direction in “combined arms” support of one another provides decisive confidence to the battalion commander that he or she has a cohesive, collaborative team. Even if all commanders happen to be moving outside of the battalion commander’s intent, it is far easier for him or her to correct the entire team at once than it would be if all company commanders were moving in different directions—whether administratively or tactically.

For those who are about to have the privilege of company command, I encourage you to embrace the opportunities, challenges, and friendships ahead. Thank the soldiers you get to serve, and make the most of every moment, because before you know it, you too will transfer the guidon and move on to the next challenge.

Capt. Harrison “Brandon” Morgan is grateful for the opportunity to have commanded the soldiers of Attack Company, 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. His operational experience includes a nine-month rotation to the Republic of Korea as a company commander, a nine-month rotation as the 1st Infantry Division’s liaison to the Republic of Lithuania, and a nine-month deployment to Iraq as a platoon leader with the 82nd Airborne Division. He served as a 2019–2020 Modern War Institute fellow, and tweets at @H_BrandonMorgan.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Sirrina Martinez, US Army