It was all about speed. Russian Army planners assessed that their combined-arms battalion tactical groups could cover the two hundred kilometers from the Belarus border to Warsaw quickly, in a few days, taking the direct approach along European Route 30. The Russians expected local resistance, but nothing that could stop the concentrated thrust of armor before it reached the objective. Once in possession of Warsaw, Moscow assumed NATO would have to negotiate, unwilling to stomach a brutal fight to retake a NATO capital. At that point Moscow could trade this prize for the ending of all post-Crimea sanctions—sanctions that had Russia’s economy on the brink of collapse. The plan was risky and bold, but offered the promise of saving Russia. Time was the key.

But Russian campaign planners failed to account for a crucial element—urban defense. As the lead Russian battalions bypassed a series of modest-sized cities—each inhabited by between fifteen and eighty thousand people—on the way to Warsaw, scattered Polish light forces were left behind the Russian advance. Clearing every city took time the Russians did not have, and forces they could not spare from the main thrust on Warsaw. While the NATO senior leadership was focused on the threat to Warsaw, and thus made that the focus of heavy NATO mechanized units, they managed to reinforce those bypassed small cities with a smattering of additional light forces. Helicopter or fixed-wing transport was too risky, given the Russian air defenses, so these light forces drove themselves into the various cities on side roads, perpendicular to the Russian advance, where gaps in the enemy forces allowed it.

From these urban sanctuaries the NATO light forces were able to both slow and attrit the Russian resupply convoys following the lead battalion tactical groups. The lead heavy Russian formations were well-armored, fast, and possessed excellent firepower, but that came with a high demand for resupply—both fuel and ammunition. When the roads passed through the built-up areas, ambush was easy from the cover of buildings. Where the roads bypassed the cities, the Russian resupply convoys were still no more than a few kilometers from urban terrain that NATO light forces could use for cover in creating their small anti-access bubbles. Against unarmored transports NATO forces could use heavy machine guns, light mortars, and guided antitank missiles to cause losses in these resupply convoys. Hit and run was the modus operandi, as NATO forces would knock out a few vehicles and then melt back into the maze of buildings, breaking line of sight within seconds.

The Russian convoys had some armored vehicles as escorts, but far less than the lead battalions had, and they rarely spotted the NATO forces until they engaged. Some Russian convoys opted to swing wide around these hazardous areas, but this cure was worse than the disease, as these new routes were longer and used poor secondary roads. For a campaign built on speed and achieving a fait accompli, these resupply delays were fatal.

The effect was similar to how light Iraqi forces in 2003, operating from the cover of Nasiriyah, harassed American supply convoys, and upset the larger American campaign timeline for the drive on Baghdad. These attacks on Russian supply lines quickly forced Moscow to make some difficult decisions. The lead Russian battalions had reached the outskirts of Warsaw, some even penetrating a few kilometers into the city, but NATO forces were now swarming to the fight. The battalion tactical groups had used considerable fuel, ammunition, and time to get that far, and now a major fight for Warsaw looked possible. Supply shortfalls forced Russian leaders to make a choice: fight forward for the rest of Warsaw or conduct a fighting retreat back to Belarus while they still could. Faced with the potential catastrophe of having its best forces cut off and destroyed, Moscow quickly dialed back its objectives and offered to negotiate.

Urban operations are both challenging and fascinating, generating no small amount of commentary within the national security community. This rich discourse is valuable and essential, but the focus is usually on tactical considerations, leaving relatively little attention to how these considerations connect to the operational level of war. The notion of the strategic corporal is commonly known, where one soldier’s error can turn a city’s population against a military force, but this is only a narrow portion of that larger campaign perspective. The difficulty of those urban tactical challenges makes them captivating, but much more attention must be paid to the connections between the urban tactical and campaign design. Retired Maj. Gen. Robert Scales made a similar point more than twenty years ago, when he called out the American tendency to bypass “core conceptual aspects of war” on the way to the tactical details of urban warfare.

Commanders and planners of real-world operations—along with wargamers (players and designers), scenario designers, and concept developers—all have to wrestle with connecting the urban tactical and campaign levels. A tool for establishing that connection could be a structured list of questions, designed to apply to any particular urban battle or campaign, involving any type of combatants. The answers to these questions, as they relate to a specific case, would help establish that connective tissue between the tactical and operational levels. Joint Publication 3-06, Joint Urban Operations does discuss how urban battles relate to larger campaigns, but this concise list of questions is aimed at complementing existing doctrine.

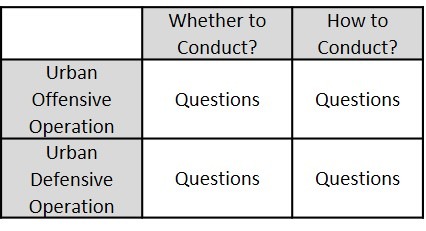

Two broad categorizations can be used to structure these questions.

- Offensive vs. Defensive Urban Operations: This refers to the type of urban operation being contemplated, not the nature of the larger campaign.

- Whether to Conduct vs. How to Conduct: Some questions relate to the decision to conduct some part of a larger campaign inside an urban area. Others shape the way an urban operation is conducted, to ensure it supports the campaign’s overall goals. This second type of questions deals with the tactical, but it links to the operational level.

These two categorizations form a two-by-two matrix (see Table 1), with four sets of questions. While this structure will result in redundancy, with some questions being useful in more than one context, this does not detract from its overall utility.

The following are four sample sets of questions, corresponding to each of the boxes in the matrix. The list is not a comprehensive one of all useful questions, but offers a good start.

Offensive Operation / Whether to Conduct

- Is bypass viable and useful?

- How do friendly forces avoid being sucked into an unwanted urban fight?

- Is isolation viable and useful?

- What is the resiliency of enemy forces if isolated in the city?

- What is the value to enemy forces in possessing that city?

- What is the value to friendly forces in capturing the city?

- What is the likely cost to friendly forces, in casualties, to capture the city?

- What is the likely cost to friendly forces, in time, to capture the city?

- What is the value of an urban feint?

- Do enemy forces have the intent and capabilities to reinforce the city once friendly forces’ intentions to attack are clear?

- What characteristics of the city make offensive operations more or less difficult?

- Do friendly forces need to capture the whole city, or just part(s)?

- What are friendly and enemy forces’ sensitivity to collateral damage and civilian casualties?

- Are friendly forces available for the attack?

- For how long?

- Are those forces needed elsewhere?

- What is each friendly force unit type’s utility for an urban offensive operation?

- What enemy forces are in the city?

- What is the enemy forces’ utility for urban defense?

- Who does the population favor, and to what degree would they lend support?

Offensive Operation / How to Conduct

- Relative to the larger campaign, how do these factors rank in terms of their importance for this urban fight?

- Time to clear the city

- Friendly losses

- Gaining use of the city for friendly forces

- Collateral damage and civilian casualties (by any cause)

- Enemy losses

- Denying use of the city to enemy forces

- Do friendly forces need the whole city, or just part(s)?

Defensive Operation / Whether to Conduct

- What is the value to enemy forces in capturing that city?

- What is the value to friendly forces in possessing the city?

- Do friendly forces need hold the whole city, or just part(s)?

- Can enemy forces be pulled into an urban fight they do not want?

- Can enemy forces bypass the city?

- Can enemy forces isolate the city?

- What is the resiliency of friendly forces if isolated in the city?

- What is the likely cost to enemy forces, in casualties, to capture the city?

- What is the likely cost to enemy forces, in time, to capture the city?

- What characteristics of the city make defensive operations more or less difficult?

- What are friendly and enemy forces’ sensitivity to collateral damage and civilian casualties?

- Are friendly forces available for defense?

- For how long?

- Are those forces needed elsewhere?

- What is each friendly force unit type’s utility for an urban defensive operation?

- Are enemy forces available for attack?

- For how long?

- Are those forces needed elsewhere?

- What is each enemy force unit type’s utility for an urban defensive operations?

- Who does the population favor, and to what degree would they lend support?

Defensive Operation / How to Conduct

- Relative to the larger campaign, how do these factors rank in terms of their importance for this urban fight?

- Time the city is held

- Friendly losses

- Preserving use of the city for friendly forces

- Collateral damage and civilian casualties (by any cause)

- Enemy losses

- Denying use of the city to enemy forces

- Do friendly forces need the whole city, or just part(s)?

- Is there potential for disrupting enemy forces and activity outside the city, from urban sanctuaries?

Campaign planners must consider a vast array of factors, while thinking jointly and accounting for Red capabilities and intent. I will leave to professional planners the above question of how structure would exactly fit into that complex orchestration. Joint experimentation and wargaming could provide a venue for testing both the question structure and content. Such testing could also yield insights for joint concept development. For example, contested logistics is now a popular topic in the concept development community, but generally from the perspective of how Blue will preserve its logistics capabilities versus a Red force with advanced capabilities. By shifting focus to near peer opponents, there may be a flip slide to contested logistics. Foes with large advanced ground forces share some of the same logistics challenges of US ground forces. As described in the earlier scenario, could US defensive operations in urban terrain offer an option for countering Red logistics, executing its own Nasiriyah?

In sum, the challenge of tactical urban operations draws a lot of attention, but the interface between the urban tactical and larger campaigns needs more. Getting to the right answers requires asking the right questions. The question framework presented here is designed to help users better understand the connections between urban battles and their respective campaigns.

Dr. Alec Wahlman has been an analyst for twenty years in the Joint Advanced Warfighting Division at the Institute for Defense Analyses, in Alexandria, Virginia. He holds a PhD in Military History from the University of Leeds (UK), and is the author of Storming the City: U.S. Military Performance in Urban Warfare from World War II to Vietnam.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Institute for Defense Analyses, United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Capt. Jennifer Cruz, US Army