The US military has embraced great power competition as its organizing principle, but cannot seem to agree on what the term actually means.

While the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) has driven a monumental shift toward great power competition, the document failed to define the term in any meaningful fashion, nor did it build a common understanding across the US military regarding what it means to actually compete. Beyond the oblique directive to do more against China and less against terrorism, America’s military has been left to organize around a defining principle that gets defined differently in the eyes of each beholder.

Take, for example, the public statements of America’s military leadership regarding great power competition. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper has declared that competition with China requires deploying troops abroad to new bases in the Indo-Pacific. Yet Gen. Mark Milley, as chief of staff of the Army, declared instead that competition requires forces at home to reorganize, refit, and retrain to prepare for high-end conflict.

The NDS itself, echoing former Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s own views on irregular warfare, asserts that part of great power competition involves information warfare, ambiguous or denied proxy operations, and subversion. Yet Secretary Esper has since declared that competition means irregular warfare is a thing of the past.

Even if competition was intended as a rhetorical big tent, these contradictory views have wildly different implications for an organization as large as the US military. Should forces be postured abroad, or trained at home? Should they prepare for high-end conflicts, or gray zone aggression? Should they do all of the above, or nothing at all?

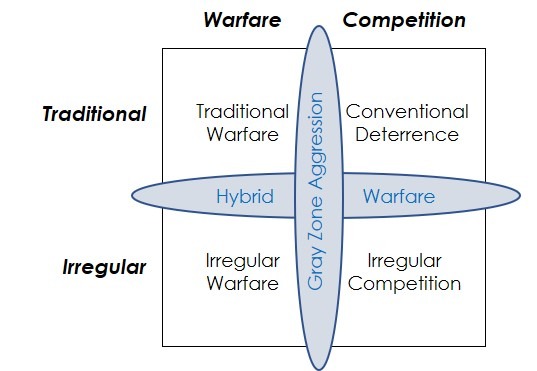

To succeed in the competition it so desperately hopes to undertake, the US military must learn to bridge the gaps between these competing visions, and embrace a new framework for understanding competition through the lens of its current approaches to traditional and irregular warfare. In so doing, the Defense Department can finally move beyond its myopic focus on preparing for great power conflict, and embrace the missing, irregular aspects of great power competition.

Back to Basics: Traditional and Irregular Warfare

A clearer understanding of the US military’s role in competition should begin with how it approaches conflict. America’s capstone military doctrine recognizes just two forms of warfare—traditional and irregular.

Traditional warfare is defined in the classic Westphalian sense, where states seek to use the military instrument to achieve “domination” over adversaries when unable to resolve differences through peaceful means. War is easily distinguishable from peace, and is waged by uniformed soldiers on clearly defined battlefields, with tangible objectives.

By the mid-2000s, however, in an effort to diagnose why military domination was the wrong strategy for Iraq and Afghanistan, the US military realized it needed new doctrine for a second, and coequal, form of warfare known as “irregular” warfare.

Rather than compelling an adversary through force, irregular warfare seeks to defeat an adversary by building legitimacy and influencing populations. Irregular wars are fought not for tactical victories in the Suwalki gap, but for influence in eastern Ukraine, and for legitimacy in contested areas like northeastern Syria and the South China Sea.

These two forms of warfare represent different approaches to compelling an adversary in conflict. As a result, they also offer insights into how the US military can employ its warfighting capabilities—both traditional and irregular—to succeed in competition.

Conventional Deterrence and Competition

The application of traditional warfighting capabilities in competition is more easily understood by the US military. Practically speaking, this is conventional deterrence.

At its core, deterrence is about discouraging states from taking unwanted actions. As a broader concept, states can deter both conventional threats, as well as nuclear and even gray zone aggression. And yet, the primary contours of America’s military-industrial complex since the start of World War II have focused on deterring conventional aggression against Western Europe, from both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Today, record Pentagon budgets are now justified by the need to deter an increasingly capable Chinese military from a conventional invasion of Taiwan, along with other similarly conventional threats.

But is deterring conventional aggression synonymous with great power competition? America’s military leaders sure seem to think so.

As secretary of the Army, Mark Esper declared in 2018, “We are in an era of great power competition [with] China and Russia and . . . we must be prepared for a high-end fight with them in the future.” The former chief of staff of the Air Force, when asked about great power competition, cited homeland defense, nuclear deterrence, and preparing for conflict as areas for further investment. Even the commandant of the Marine Corps’ ambitious redesign efforts for great power competition are premised upon “naval expeditionary warfare in actively contested spaces.”

When viewed through the lens of conventional deterrence, competition is reduced to the correlation of forces between the US Army and China’s People’s Liberation Army, the vulnerability of allied airbases in the Indo-Pacific to missile attack, and the posture of NATO-led rotational battlegroups in the Baltics.

But if America recognizes two forms of warfare—traditional and irregular—should it not also recognize two forms of competition? Phrased differently, if the US military focuses solely on deterring conventional threats in competition, is that sufficient to challenge China’s and Russia’s competitive strategies?

The Irregular Half of the Competition Equation

While much of the Pentagon remains laser-focused on the conventional threats posed by great powers, the NDS itself pays considerable deference to the irregular aspects of competition.

In its diagnosis of the strategic environment, the NDS declares that “China is leveraging . . . influence operations, and predatory economics to coerce neighboring countries,” and that Russia seeks “to discredit and subvert democratic processes” throughout Eastern Europe. It also emphasizes that great power competitors have “increased efforts short of armed conflict by expanding coercion to new fronts, violating principles of sovereignty, exploiting ambiguity, and deliberately blurring the lines between civil and military goals.”

These asymmetric threats fall well outside the US military’s understanding of its role in deterring conventional aggression. And yet, the NDS makes clear that the military’s failure to address the full spectrum of great power competition “will result in decreasing U.S. global influence, eroding cohesion among allies and partners, and reduced access to markets.”

Given the NDS’s discussion of these irregular threats, the lack of public rhetoric from US military leadership to this effect is troubling. This is perhaps a consequence of the NDS’s failure to define this space clearly. More likely, it is a symptom of the US military’s historic struggles to understand its role in irregular conflicts beyond the tactical defeat of an adversary.

But the United States has clear doctrine for irregular warfare, borne out of the realization that not all conflicts can be won through the linear application of force. Applying this approach to competition, rather than conflict, makes the missing half of the competition equation much clearer.

Just as irregular warfare seeks to gain legitimacy and influence in conflict, the NDS embraces a form of competition in which states vie for legitimacy and influence through coercion and subversion, malign influence, proxies, and predation. Viewed in this context, Chinese island building in the South China Sea is just as much about forward staging of air defense capabilities as it is about challenging the legitimacy of Vietnamese and Philippine claims to sovereignty on China’s periphery. Similarly, Russian aggression against Ukraine and Georgia is just as much about challenging NATO posture as it is about eroding Western soft power in the former Soviet sphere.

In fact, when viewed on a continuum, a holistic understanding of competition emerges. Just like the divide between traditional and irregular warfare, the US military must acknowledge competition’s two, coequal parts—the threat of military domination through conventional deterrence, and the contest for legitimacy and influence through irregular competition.

This approach would allow policymakers and planners to design strategies that unleash America’s own irregular warfare capabilities in great power competition. Moreover, it would allow Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps leadership to invest in irregular warfare capabilities most relevant for competition, rather than eliminate these capabilities simply because they were once used to support counterterrorism.

Hybrid Warfare and Gray Zone Aggression

This framework also helps reconcile two other terms that are used interchangeably with competition—hybrid warfare and gray zone aggression.

In this context, hybrid warfare can be defined as the application of both traditional and irregular approaches in a given campaign. In this way, hybrid warfare describes the ambiguous methods used by a state to achieve its objectives. This is demonstrated best by Russia’s use of “little green men,” an irregular tactic, to pave the way for an otherwise conventional annexation of Crimea. US doctrine actually embraces this logic, noting that “warfare generally has both traditional and irregular dimensions.”

Gray zone aggression, then, describes a state’s limited use of violence to advance its interests, intentionally blurring the line between peaceful competition and all-out warfare without provoking escalation into conflict. In this way, gray zone aggression describes the ambiguous intent behind a state’s escalation in a given campaign, rather than the methods used to escalate. This approach is seen clearly in China’s recent violent confrontations with India near Aksai Chin.

While the United States prefers to operate along the edges of this continuum—swinging wildly between its embrace of counterinsurgency in 2007 and its singular emphasis on high-end conflict under the 2018 NDS—the reality is that America’s adversaries prefer to exploit these seams.

Filling in the Seams of Great Power Competition

The implications of failing to understand the two halves of competition, and the seams between them, could be catastrophic for efforts to achieve the NDS’s vision for great power competition.

While America prepares for a traditional war neither Russia nor China seems eager to fight, these competitors are busy shaping conditions to their advantage through proxies, denying the United States military access to key terrain through coercion, and eroding American influence through disinformation—all without firing a shot.

This does not mean that the United States should abandon conventional deterrence as a fundamental priority. Without this strength, an adversary could prioritize conventional aggression once again to great effect.

However, because of this strength, America must acknowledge that shrewd adversaries will emphasize indirect approaches in response. Sophisticated adversaries may even pursue investments in high-tech capabilities to incentivize the United States to spend ever-increasing sums of its own wealth, chasing declining marginal gains in lethality.

A myopic understanding of competition risks rendering the American public’s $730 billion annual investment in its military useless against significant threats to America’s security. It risks unwise resourcing choices that de-emphasize missions and skills needed to gain legitimacy and influence in competition, such as information operations, intelligence and logistics support to allies, special operations forces capable of working with local partners, and even policy expertise within the Pentagon and National Defense University.

While still nascent, some concrete steps have been taken toward embracing the irregular half of the competition equation.

The Irregular Warfare Annex to the NDS, endorsed by Secretary Mattis and approved by Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan in 2019, declares that America will proactively employ its irregular warfare capabilities in great power competition “as a means to help expand the competitive space, defeat our adversaries’ competitive strategies, and set the globe for transition to crisis.” The Pentagon has begun to implement this strategy, the only annex to the NDS, seeking to dictate “the character, scope, and intensity of our competition with adversaries.”

Similarly, the US Army’s continued investments in the growth of its security force assistance brigades retain critical expertise in building partner capacity, and free up conventional brigade combat teams to focus on traditional warfare requirements.

The 2020 National Defense Authorization Act also establishes a principal information operations advisor to the secretary of Defense, and opens up a legal framework for the US military to engage in the types of non-attributable messaging that have come to define modern information statecraft.

These changes are a start. But the Department of Defense and its leadership need to publicly embrace both sides of the competition equation, drive this thinking into budgets, and push back against the impulse to reduce competition to preparing for conflict alone.

Until then, America risks losing the competition it faces today, while waiting for just the right type of war to come tomorrow.

Eric Robinson is an analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation. Previously, he was the Irregular Warfare Policy Chief in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy from 2017 to 2020.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: 1st Lt. Benjamin Haulenbeek, US Army