Recently, Modern War Institute Non-Resident Fellow ML Cavanaugh wrote an article for this site called “Fifty-One Strategic Debates Worth Having,” in which he lists 51 debate topics he felt were important to those that think about national security. These topics run the gambit from “Pushbutton, standoff warfare is cowardly” to “Iraq was worth it.” I agree wholeheartedly with Cavanaugh that we should have a lively discussion on many of the topics he proposes. With that in mind, I would like to start by weighing in on one of those topics, that “there will never be another need for a mass airborne drop.” Although such a premise will surely have doubters among airborne ranks, a quick look at the nature of the world in which we live and fight makes clear that it is true.* In the spirit of debate suggested by Cavanaugh’s list, I’m looking forward to hearing from those of you who wish to prove me wrong.

In the potential Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) environments created by Russia, China or another near-peer competitor, and with the proliferation of accurate and effective air defense weapon systems, attempting a mass airborne operation today would result in a substantial loss of lives and aircraft, significantly reducing its tactical and strategic impact. This type of operation, which calls for a C-17 carrying approximately 100 paratroopers to fly low (planning altitude of about 800 ft. AGL) and slow (130 knots is ideal), plays right into the hand of an enemy that values air defense over air supremacy.

The Vulnerabilities of Airborne Operations

The Army’s manual on Airborne and Assault Operations, FM 3-99 lists the following vulnerabilities inherent to airborne operations:

- Attack by aircraft and air defense weapon systems during the movement and airborne assault phases.

- Attack by chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons because of limited chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear protection and decontamination capability.

- Attack by ground, air, or artillery during the assault and landing phases.

- Air strikes if air superiority is not gained before the airborne assault.

- Electronic attack, to include jamming of communications and navigation systems, and disrupting aircraft survivability equipment.

- Small-arms fire that presents a large threat to the aircraft during the air movement, airborne assault and landing phases.

For this discussion let’s focus on the first vulnerability, attack by aircraft and air defense, because you can’t have an effective airborne operation if all your aircraft are shot down before the paratroopers can jump out. Not since the Vietnam War has the U.S. Air Force had to contend with an air defense system that was effective in shooting down aircraft. The Vietnamese were successful because they used an integrated air defense system created by the Soviet Union. Over 120 aircraft were lost during the Vietnam War to surface-to-air Missiles (SAM). Iraq, on the other hand, used an air defense system during the 2003 invasion that was comparatively older and less capable, and relied more heavily on guns. With that said, I can only find reference of one fixed-wing aircraft being shot down by a SAM during the recent war in Iraq.

The Russians, and others, learned from our experiences. They determined that while they probably can’t match our air-to-air capability they can compensate for it with an overwhelming integrated air defense system. Unlike U.S. forces, the Russians and other near-peer militaries incorporate air defense from the strategic down to the company-sized unit level.

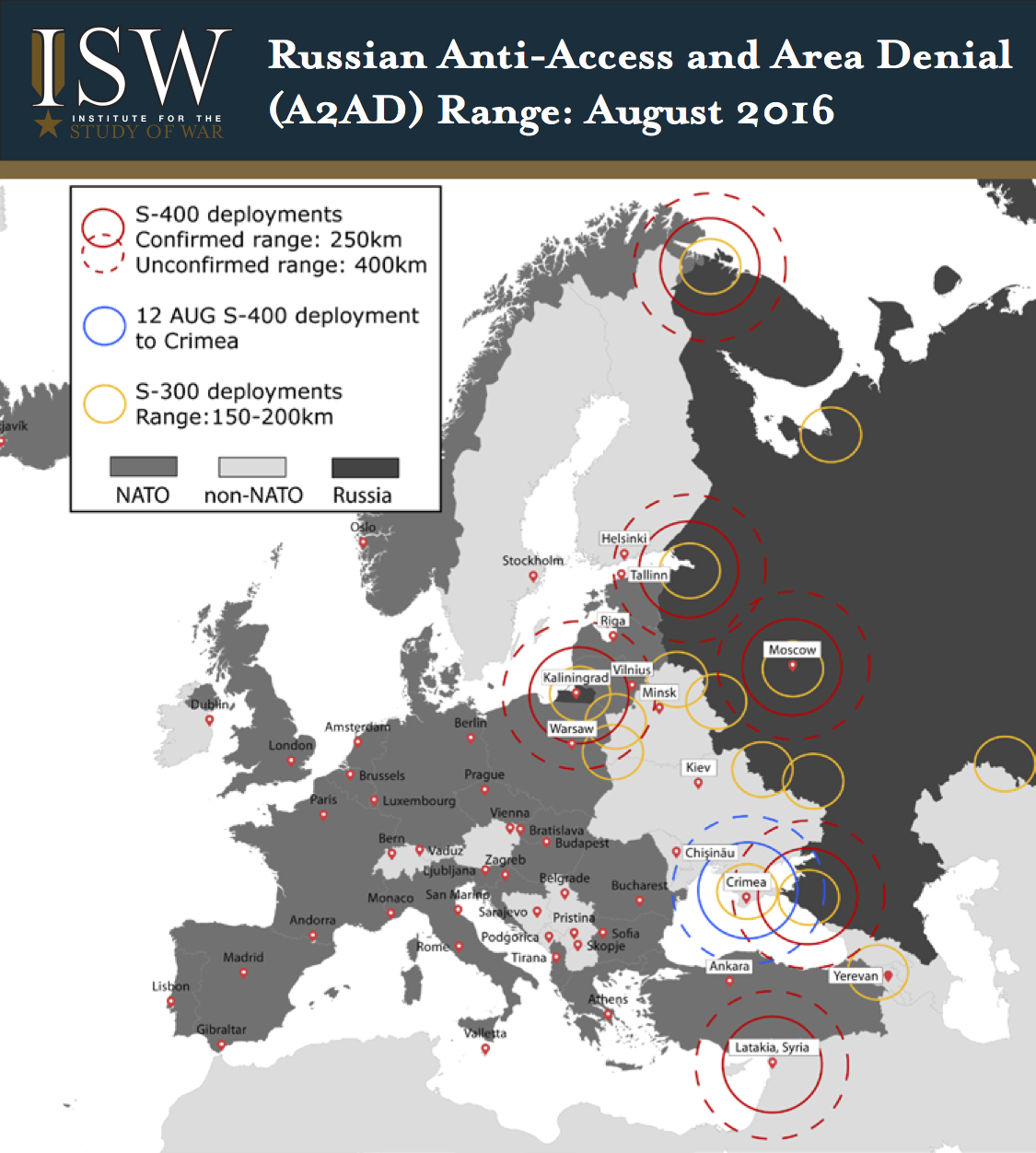

For the purpose of this argument let’s focus on Russian forces. At the strategic level Russia has at their disposal the S-300 and its upgrade the S-400. As shown in the figure below this system has been deployed to create a bubble of defense along Russia’s border with NATO.

According to open sources the S-400 is equipped with multiple missile variants, which are capable of hitting aircraft or missiles at a range of between 40 and 400 km. It’s possible that if enough of the S-400’s associated radar systems are working in conjunction they could be capable of tracking stealth aircraft like the F-117, F-22, and F-35. With over 150 systems currently deployed they are slowly replacing the S-300, which is capable of tracking over 100 targets (compared to 300 for the S-400) at a range of up to 150–200 km.

At the operational and tactical level Russian forces have at their disposal several different systems, including the SA-17, which has a range of up to 30 km. These systems can be found at the corps and division levels of most orders of battle. They are typically tasked with defending higher-echelon headquarters and other high-value targets. Another system, the 2S6, can also be found at the division level, and possibly task-organized down to brigades. In addition to the 2S6, many brigade-level units will have older ZSU-23-4’s. These systems can range targets out to 10 km and engage targets out to 2.5 km.

The disadvantage to all of the above systems is our ability to conduct effective Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses, known as SEAD, through either electronic or kinetic fire means. Most large, vehicle-based, air defense systems are vulnerable to SEAD operations. Successful SEAD gives a window of opportunity for airborne forces to pass through the enemy’s large air defense systems without completely destroying the integrated defense network.

There is, however, an air defense system that SEAD is ineffective against — man-portable air defense systems or MANPADS. One of the most well-known MANPADS is the Stinger missile. The Stinger gained notoriety as the weapon that helped beat the Soviets in Afghanistan after the CIA began supplying them to mujahedeen fighters to help protect them against Soviet helicopter gunships.

The Russians and other militaries today field a weapon similar to the Stinger in the SA-24, and Russia also fields the newer SA-25. Both of these systems fire a heat-seeking missile capable of hitting targets up to 5–6.5 km away. These systems are fielded down to the company and platoon level making this system, one that litters the battlefield, nearly impossible to conduct effective SEAD operations against.

This means that even if effective SEAD allowed an airborne force to make it through the strategic- and operational-level air defense systems, it would have to contend with dozens of MANPADS when its aircraft were at their most vulnerable, on its run over the drop zone. These MANPADS would not be locatable until they were fired, so overcoming the threat they pose would require aircraft to take evasive action, which is not possible while in their drop run, or rely on the heat-seeking countermeasures that are only semi-effective.

The problems for the airborne force don’t stop after it gets through the air defenses. Since many of the aircraft that were used for transporting paratroopers will also be used to send in resupplies, logistics plans will have to be adjusted to account for lost aircraft and personnel. The Little Groups of Paratroopers, or LGOPs, will have to find ways to consolidate, inevitably while under fire from significantly overmatched weapon systems. Without large weapon systems being brought in with resupply missions, these LGOPs will be outgunned and easily defeated.

The glory days of D-Day and Market Garden-sized airborne operations are no more. The dramatic increase in accuracy in air defense weapon systems has significantly decreased the potential survivability of aircraft involved in this type of mission. This is particularly true during their runs over the drop zone, when they are required to fly low, slow, and steady. Simply put, the limited tactical advantages of large, modern-day airborne operations are overshadowed by their potential strategic loss. The Army should therefore shelve mass airborne operations, instead limiting them to small drops of special operation soldiers.

*To head this accusation off at the pass, I am airborne qualified and I have been on jump status. So we can get past the “he must be a dirty, nasty, leg” comments and on to a more lively debate.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Jason Robertson, U.S. Air Force