The modern Army has access to more information than ever before on the battlefield, saturating leaders with a constant bombardment of data that shapes decision-making. Technology makes things change at an ever-increasing rate, putting leaders under pressure to make the correct and timely decision. In a world where data-informed and experience-driven leaders want their formations to remain lethal on the battlefield despite bureaucratic necessities, efficient staff processes can influence success or failure of an organization. A battlefield necessity for higher-echelon formations, an effective staff can be a combat multiplier that shapes a conflict phases beyond the current fight.

It’s a common experience in most Army organizations to spend a large part of day-to-day work fighting off last-minute tasks and dealing with crises that pop up, seemingly from nowhere. The chaos that exists in most Army organizations is like a knife fight in a phone booth, leaving leaders, staff, and troops feeling exhausted and anxious. The feeling of success after surviving another day may create a euphoric sense of accomplishment but the only real accomplishment is just that: surviving. The Army is full of different tools and methods to develop plans that help the organization manage workflow within the organization and increase predictability across the formation.

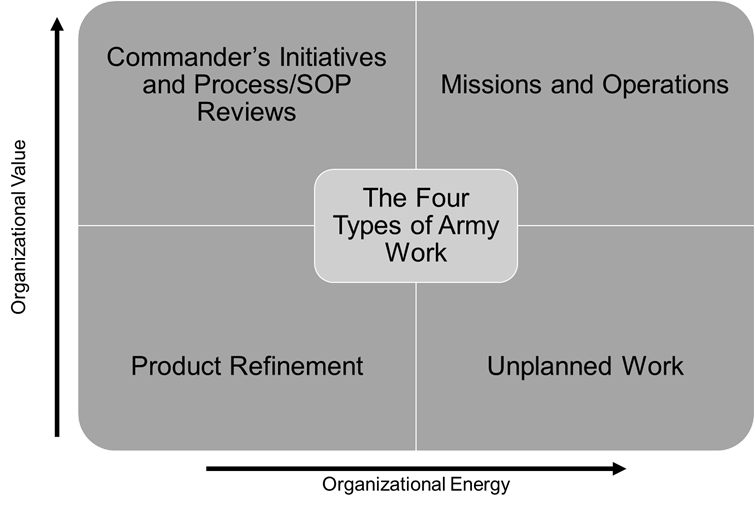

Why then, with all these tools and methods, do so many organizations face the challenge of maintaining predictability and planning beyond the next few weeks? That predictability is elusive. It always seems just out of grasp—if we can just get past this one last hurdle, then everything will slow down. That unpredictability comes from an inability to see the actual amount of work in process across the organization. In an Army staff, that work in process revolves around the flow of useful information. Much like a manufacturing plant, an Army staff has a workflow that can be managed and prioritized, but only if the unit tracks and prioritizes what is important. To do that, staffs should borrow a couple of ideas from the manufacturing field: (1) the four types of work and (2) the theory of constraints.

The four types of work, popularized in the book The Phoenix Project, establish a way to categorize work that the organization is trying to accomplish at any given time. Written as a novel, the book centers around IT operations and puts work into four categories: business projects, internal projects, changes, and unplanned work. The novel’s characters learn about the four types of work and how to improve their organization while experiencing scenarios any staff member can associate with. These types of work have a direct correlation to those found in an Army headquarters.

The Army equivalent of business projects is missions and operations. The main things any Army organization does are the missions and operations it is assigned. These are direct orders received from a higher headquarters or implied orders from tasks given from a higher headquarters. These almost always receive an operational planning team and some degree of the Military Decision-Making Process. They (should) receive the highest amount of organizational energy and dedicated staff planning support. The goal is to conduct a deep analysis of what needs to be done and a thorough plan-generation process, while receiving leader feedback throughout. Ideally, this results in early notification of a plan that is well thought out to subordinate units who can then execute that highly rehearsed plan. In reality, a staff frequently faces time constraints, delayed decisions, or unforecasted issues that force staff members to abbreviate steps, miss key details, or delay publication of an order.

The Army equivalent of internal projects are things like commander’s initiatives and standard operating procedure reviews. These are generally things that make the organization better or are required to remain in compliance with policies. They typically are managed by either a special project officer or as an additional duty and executed around regular missions and operations. They may be required by regulation and frequently have checklists. A common one, filled with checklists, is the Command Supply Discipline Program. These are things designed to keep the organization running smoothly at a high readiness level (if you maintain good supply discipline, you can find and use your equipment when ordered to execute a mission) but also demand a certain level of leader and staff commitment to maintain compliance with regulations. In the Army, these quickly gain leader visibility when they fail but are not the primary reason for the existence of the organization. If the project is a review of procedures, it typically will ebb and flow based on other events and priorities in the organization. Unfortunately, if given too much dedicated effort, these projects can quickly become the sole effort for an organization—to remain in compliance with all policies and regulations despite any cost to readiness.

The Army equivalent of changes is product refinement. There is always some poor soul on staff who is responsible for making edits to slides or orders to get them from pretty okay to good enough to publish or present. This, while generally a minor task that can be accomplished quickly by the right person with a proclivity for Microsoft Office products, still requires a certain amount of time and effort. It is common for leadership to approve a product with caveats, requiring modification before the product is (often temporarily) complete. Any staff officer can tell you a war story of how he or she wasted an entire day editing one slide over and over again. This category is inevitable, especially because the real goal of a staff is throughput of useful information. To ensure throughput of information, a certain degree of good enough must apply with the understanding that as things develop over time, changes will be required.

The Army equivalent of unplanned work is . . . well, unplanned work. This is everything that keeps you from crossing things off your to-do list. Whether it is a serious incident report, a missed tasking, a changing environment in combat, or simply something the staff missed during the Military Decision-Making Process, this is all the work that has to happen immediately. This is generally where an Army organization thrives (and where the Rapid Decision-Making and Synchronization Process resides) due to the unit’s ability to come together in a crisis to solve problems. All of these are things that no one really wants to have to do, but require massive amounts of energy to resolve. An unfortunate side effect is the addictive feeling of accomplishment and camaraderie that results from averting a near catastrophe together. This type of work is also inevitable, but it detracts from the main things an organization wants to accomplish. There are ways to mitigate this through improving support to the other types of work and projecting future work better. There will always be crises and environmental factors within the military that will force units to spend some energy in this category, however. The best option is to put a competent person in charge of this type of work and focus organizational effort on the other areas.

Now that the types of work are identified, how does an organization avoid unplanned work and dedicate energy to improving the workflow? This is where the theory of constraints becomes important. For those unfamiliar with this theory, The Goal by Eliyahu Goldratt is a good starting point. The simplified version is that an organization must focus on throughput as a primary measurement. It does this by identifying the constraints (or bottlenecks) in its workflow system. Once those are identified, all workflow is oriented around maximizing the throughput of those constraints. Conceptually, it works like putting a pace vehicle at the front of a convoy or the slowest runner at the front of the formation. If the entire system is limited to the slowest component, the system is less likely to become disorganized or have to readjust continually. This continuous subordination of the overall system to the constraint is the critical component of managing the workflow. Every staff will have an element—either a process or person—of such critical capability that it becomes a constraint. Managing the throughput at that constraint becomes critical to success of the organization, and often that of subordinates.

In an Army staff, useful information flow is the workflow that needs to have throughput optimized. To do this, the organization first has to identify the work in process within the organization, identify the work it must or wants to do, and dedicate resources to those projects. While a staff will commonly apply significant effort and resources to the more immediate problems in unplanned work, committing more energy to long-term business projects reduces future unplanned work by producing better planned work. For example, if an order is produced early but incomplete or unrefined it has simply transitioned from the missions and operations category to the refinement category. If this is done early in the process and includes continuous feedback, the organization can receive bottom-up refinement from subordinate organizations and improve the overall project. This also doubles as an opportunity for the information to reach subordinate units and increases overall understanding. The result is that, by the time information gets to the execution stage, it is going to inherently include less unplanned work by the sheer fact that the increase in feedback results in fewer problems.

The management of workflow is a common manufacturing theme but it also applies to an Army staff. It is a virtue of an Army organization to be able to thrive in chaos, but it does not have to always be that way. A better understanding of the workflow and work in process in the system creates a degree of visibility that is the first step toward identifying the constraint. Then it is a matter of prioritizing work around that constraint to improve the system overall.

Leaders that understand how to manage and prioritize work within their organizations will find themselves with staffs that are combat multipliers instead of bureaucratic hindrances. An initial step toward the vision described in the 2022 National Defense Strategy—specifically in Section V, “Campaigning”—improved staff processes can develop a better understanding of the operating environment. A better understanding of the operating environment enables commanders to make better and more informed decisions—faster. Through this, formations can more consistently position themselves at an advantage against adversaries by planning and preparing for operations phases in advance. That, in today’s complex environment, is one way to balance being consistently postured to win over time while maintaining organizational flexibility to compete in any unique scenario.

Major Garrett Chandler is a planner at the 4th Infantry Division and a graduate of the School of Advanced Military Studies. He previously served as the course director for the Army’s Supply Chain Management and Master Logistician courses at Fort Lee, Virginia. He holds a master’s degree in supply chain management from Virginia Commonwealth University and a graduate certificate in business analytics from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Spc. Charles Leitner, US Army