In March 2022, the Pentagon released a new National Defense Strategy (NDS) that identified China as the “most consequential strategic competitor” of the United States. The NDS also described two concepts—integrated deterrence and campaigning—as primary means by which the Department of Defense will seek to address the challenge posed by China, as well as lesser challenges posed by other actors. Ten months later, however, DoD has still not issued specific guidance on how to conduct effective campaigning in support of integrated deterrence.

As part of a broader study that I recently led for a DoD sponsor, I identified the critical components of campaigns—in other words, the specific types of military activities—that would enable the United States to compete with state adversaries, in line with the concepts described in the NDS. The resulting framework has the potential to help US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) position itself as the force of choice for competition campaigning and avoid further reductions in its budget and force structure. It can also help the Pentagon sharpen its existing campaign plans and assist the relevant congressional committees as they think about oversight of the Pentagon’s approach to strategic competition.

Competition Campaign Design

The central concept of the 2022 NDS is integrated deterrence, which seeks to combine deterrent effects across warfighting domains, geographic regions, the spectrum of conflict, elements of US national power, and US allies and partners. But the NDS also focuses on the idea of campaigning, which it says DoD must conduct to “strengthen deterrence and enable us to gain advantages against the full range of competitors’ coercive actions” and “to undermine acute forms of competitor coercion, complicate competitors’ military preparations, and develop our own warfighting capabilities together with Allies and partners.” While the US military routinely conducts campaigns—defined as “the conduct and sequencing of logically-linked military activities,” day after day, “to achieve strategy-aligned objectives over time”—in wartime, the NDS’s emphasis on campaigning is focused on improving the military’s ability to do so in preconflict, competitive settings. In this regard, the focus on campaigning in the 2022 NDS is, to a large extent, an extension of the emphasis in the 2018 NDS on strategic competition.

These ideas have helped orient the US military in distinctly different ways than the wars of the past twenty years, but they leave significant questions unanswered. For example, what does a competition campaign in support of integrated deterrence look like in practice? Is it just the same as the global campaign plans focused on specific adversaries? Does it simply comprise the collection of theater campaign plans advanced by the geographic combatant commands? Or is a strategic competition campaign somehow different from these extant plans? The NDS does not specifically address these questions, but the answers to them are “no,” “no,” and “yes,” respectively.

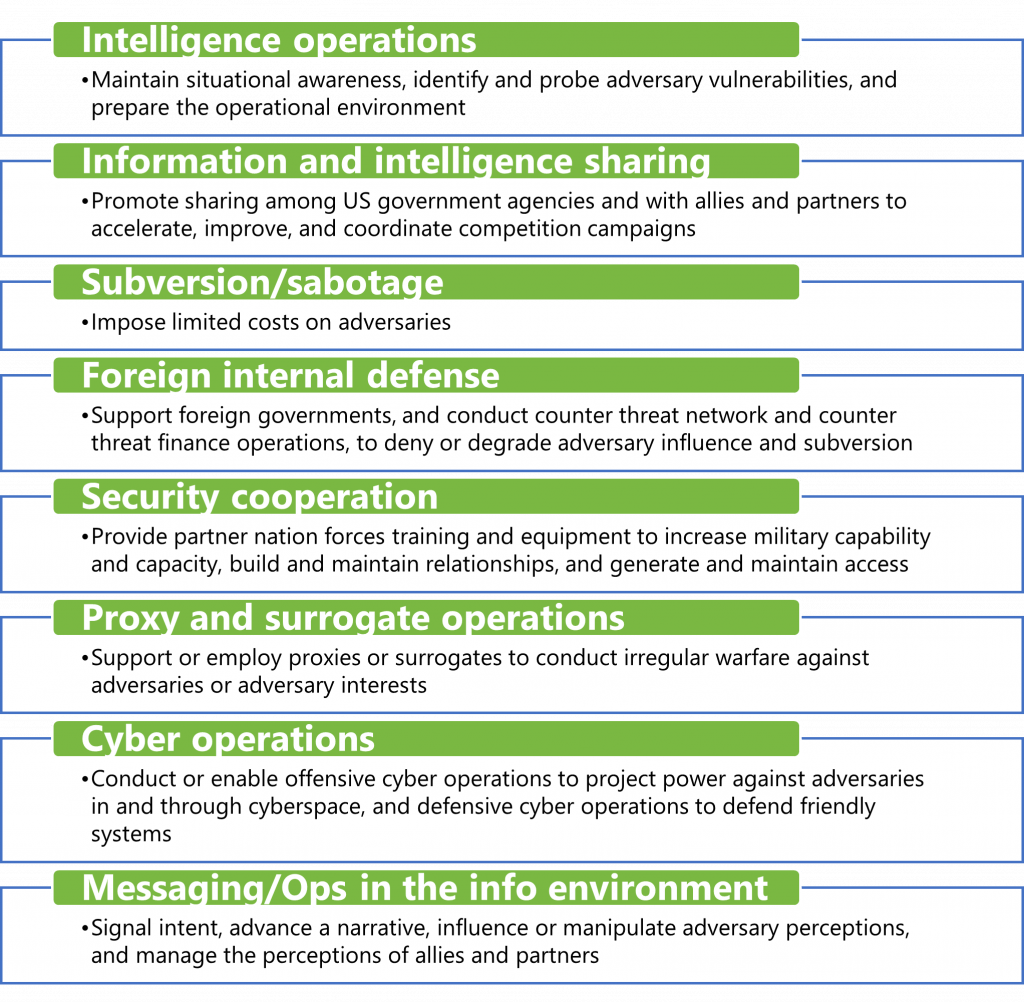

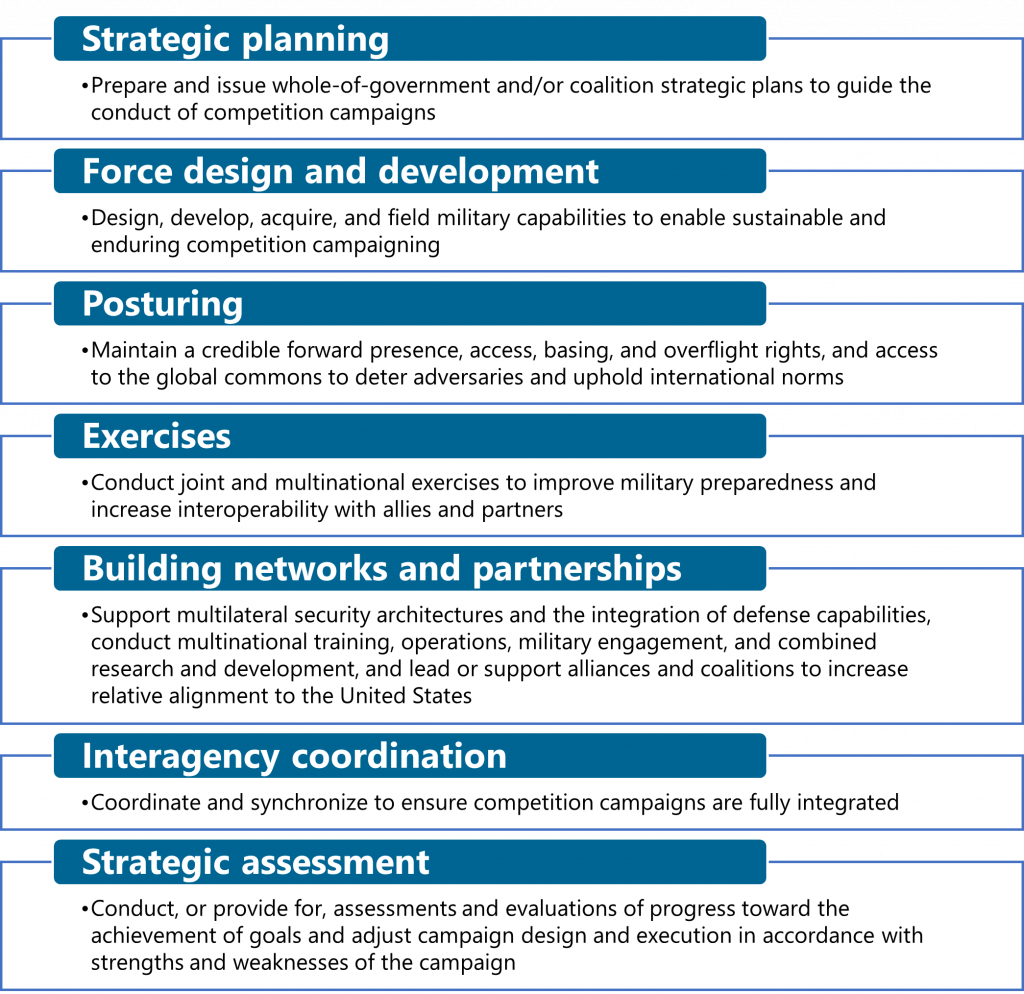

To identify the specific activities that the US military should pursue as part of competition campaigning, I examined a variety of US government documents that are specific to competition—including Joint Doctrine Note 1-19, the Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning, and the draft Joint Concept for Competing (which has subsequently been folded into the Joint Warfighting Concept). I also reviewed scholarly articles on competition from CNA, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the RAND Corporation, and the Center for a New American Security, as well as independent publications by various scholars. In each document, I looked for and cataloged the specific military activities and capabilities the authors described as being necessary for competition. Drawing a cut line at those items called for by at least one government and multiple scholarly sources resulted in the list of campaign components shown below.

Features of the Campaign Design

In looking at the fifteen components of campaigning in competition that I identified, some will be familiar to those who have been involved with US military campaigns against terrorist groups: intelligence operations, information and intelligence sharing, security cooperation, messaging, the use of proxies, interagency coordination, and building networks have been key elements of the wars of the past two decades. The specific ways in which these activities get applied to competition with state adversaries, however, may look significantly different in practice from their use against terrorist threats. For example, while terrorist groups like the Islamic State have some ability to detect and disrupt US intelligence operations, conducting such activities against the likes of China or Russia—which have vastly more advanced counterintelligence capabilities—would look qualitatively distinct. Other components of competition campaigns, however, may surprise some readers. Strategic planning, force design and development, posturing, exercises, and strategic assessment are elements that were not often highlighted as part and parcel of efforts to counter terrorist groups. As a result, the skills and capabilities required to conduct these activities have atrophied across much of DoD.

Interestingly, the fifteen components of competition campaigns break out nearly evenly between two categories. The first (in green) are operational activities, largely conducted to compete for advantage today. The second (in blue) are largely institutional activities, conducted to compete for advantage in the future. As both the temporal and operational/institutional distinctions might suggest, these two sets of elements can be—and often are—in tension with each other. For example, the geographic combatant commands—which primarily conduct the activities in green—focus largely (via their theater campaign plans) on competing with our adversaries today and over the next two to three years. The military services—which conduct many of the activities in blue—are increasingly focusing on designing and generating forces that will have the capabilities and readiness to face challenges in the 2030–2040 timeframe. Debates often arise when tensions flare between these two categories: for example, when the services make decisions to divest themselves of capabilities that might be useful for current competitive activities in favor of investing resources to develop capabilities that might not come online for a decade or more. Because of the way DoD and the US government is structured, the only authorities who can effectively resolve these debates are the secretary of defense or the US Congress.

Implications for USSOCOM

While the tensions just described play out at a macro level within the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill, they also play out within the special operations enterprise, as a result of the unique nature of USSOCOM. Because Congress endowed USSOCOM with both combatant command (via Title 10, US Code, Section 164) and service-like authorities (via Section 167), the USSOCOM commander is the only entity in DoD aside from the secretary of defense that sits atop both operational and service components. The former, in the form of the seven theater special operations commands, center on supporting their geographic combatant commands’ priorities to compete for today. The latter, in the form of the four special operations service components—Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps—are increasingly focusing on designing and developing special operations forces (SOF) for the future.

This arrangement creates challenges for USSOCOM, which must adjudicate tensions that arise between the theater special operations commands and its service components when it comes to the design, allocation, and employment of SOF. But it also creates opportunities for USSOCOM to organically manage that tension by identifying and providing guidance for how to integrate and synchronize activities to compete for today with those designed to create future competitive advantages. In short, USSOCOM should be able to turn the crank of force design, force development, and force employment faster than any other part of DoD, which should lend it an inherent advantage when it comes to generating innovative capabilities and force packages designed for competition today and in the future.

Unfortunately, USSOCOM is not currently positioned to fully seize this advantage. Over the past two decades, SOF have enjoyed unparalleled intelligence and operational advantages over their nonstate adversaries. One result of this is that an emphasis on operations—and procurement to support current operations—has dominated the focus of USSOCOM for years. The command’s ability to effectively conduct some of the institutional elements of competition campaigns—most notably, strategic planning, force design and development, and posturing—have atrophied. Anyone familiar with USSOCOM headquarters can, for example, appreciate the dominant size and stature that the operations directorate (J3) has over the plans directorate (J5). For USSOCOM to reap the advantages of its unique blend of authorities for integrating the yin and the yang of competition campaigns, it will need to reinvigorate and invest in the people, processes, and priority of its J5 relative to other staff sections.

Assuming for the moment that USSOCOM rebalances itself accordingly, the command will still face three key issues when it comes to synchronizing the two halves of competition campaigning. First, it will need to identify the key problems that it—and only it—can solve for the joint force of the future. Potential examples might include finding ways to serve as a key set of sensors for the Joint All-Domain Command and Control concept, conducting operational preparation of the environment and information operations, ensuring cross-domain and transregional integration, or imposing costs in other theaters as part of “horizontal escalation” in the context of a localized conflagration with the likes of China or Russia. USSOCOM will also need to come to terms with the idea of playing a supporting role to the joint force, as opposed to being the supported entity as it was consistently for the past two decades. This will necessarily entail spending some of its own Major Force Program-11 funding on capabilities that are inherently designed to support the joint force, as opposed to using that funding exclusively for its own needs. These ideas represent major cultural shifts for USSOCOM and its constituent forces.

Second, USSOCOM will need to identify the proper balance between the operational and institutional aspects of campaigning for the SOF enterprise. Only recently has the command backed away from an overriding emphasis on deploying as many of its forces forward as possible, in part because of issues identified by its comprehensive cultural review. Going forward, USSOCOM will have to continuously strike a balance of current operations to disrupt terrorist groups and generate competitive advantages today and activities designed to identify, generate, and field forces that can maintain advantages against state adversaries for what could easily be several decades’ worth of competition and low-intensity conflict.

Third, the USSOCOM commander will need to decide to what extent he wants to serve as a director of future SOF design versus being an integrator of his components’ efforts. The latter would currently be an easier role for USSOCOM headquarters to play, both because of the atrophy of its force design and development capabilities and because its service components are all at least two to three years ahead of it in this regard (its Navy and Air Force components, for example, have already undertaken major force optimization and reorganization efforts to better align themselves with the NDS and their service priorities). Given USSOCOM’s institutional preferences, however, it will probably want to serve a more directive role. Being more than a force integrator will require USSOCOM to immediately rebalance its headquarters, quickly develop a substantive vision for integrated SOF of the future, and engage in a virtuous cycle of force design, analysis, and experimentation that can leapfrog its own components’ efforts to date.

In some ways, the current environment surrounding the notion of competition campaigning is reminiscent of the immediate aftermath of 9/11. At that time, there was a strong impetus to get after the problem of terrorism, but with minimal strategic guidance. The net result was some overarching principles and a lot of good ideas generated at the tactical level, with little in the way of concrete translation of principles to action. It took well over a decade of sustained counterterrorism operations before the messy middle between policy and action was cemented in the form of systemic operations orders and associated authorities. Today, the special operations enterprise—and DoD more broadly—is lacking the translation of ideas like strategic competition and campaigning to tactical actions via a clear framework of activities and associated authorities, policies, permissions, and oversight. The competition campaign framework described here should help considerably in making that connection.

More specifically, I recommend that the assistant secretary of defense for special operations and low-intensity conflict should direct USSOCOM to center the next iteration of its Campaign Plan for Global Special Operations on this framework. The Office of the Secretary of Defense should also use it as the organizing framework for the next Guidance for the Employment of the Force and the Joint Staff should use it similarly in the next iterations of its global campaign plans for specific adversaries. Finally, the pertinent congressional committees should employ it as a framework for thinking about authorities, resources, and oversight of DoD’s competition activities.

In addition to addressing the translation of policy to action, this campaign framework makes clear that USSOCOM and its forces have a unique advantage within DoD when it comes to being the force of choice for competition, because of its unique blend of operational and service-like authorities. To fully realize that advantage and position itself within DoD accordingly, however, USSOCOM will need to quickly rebalance to reinvigorate the institutional aspects of competition that are necessary to effectively compete for the future. If it can do that, USSOCOM will enable SOF to claim their rightful place as DoD’s premier force for competition for decades to come. If it fails to do so, SOF will likely face a diminished future as a force holding the line against terrorist groups and facing sustained reductions in size and stature. USSOCOM has the authorities to shape its own future and that of the global competitive landscape as well. Whether it has the vision and wherewithal to use those authorities to that end remains an open question.

Dr. Jonathan Schroden directs the Special Operations Program at the CNA Corporation, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research and analysis organization based in Arlington, Virginia. You can find him on Twitter at @jjschroden.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or any organization the author is affiliated with, including CNA.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Marcus Fichtl, US Army