Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy recently signed a memorandum that increased the ADSO—or active duty service obligation—for Army pilots. Starting in October, all personnel selected to attend the Army’s initial entry aviation training will incur an ADSO of ten years upon graduation from flight training—a dramatic increase from the previous six-year commitment.

The extended ADSO is intended to increase Army pilots’ retention in the future. Unfortunately, it will likely not have the opportunity to do so due to the negative impact it will have on retention in the near term. The service should find a better way of addressing its shortage of pilots.

Why Now?

All branches in the military are facing a pilot shortage. The Department of Defense released a report in July 2019 that laid out the challenges the military faces with pilot retention and included plans of action from each branch.

The report focused on the unmet demand for pilots in the commercial aviation sector that has attracted military pilots. Commercial airlines offer higher salaries, more career control, and stabilization. Additionally, because of rules that the Federal Aviation Administration has put into place over the last decade that make hiring civilian pilots difficult, many regional airlines have created rotary-wing transition programs that substantially ease the transition for Army helicopter pilots.

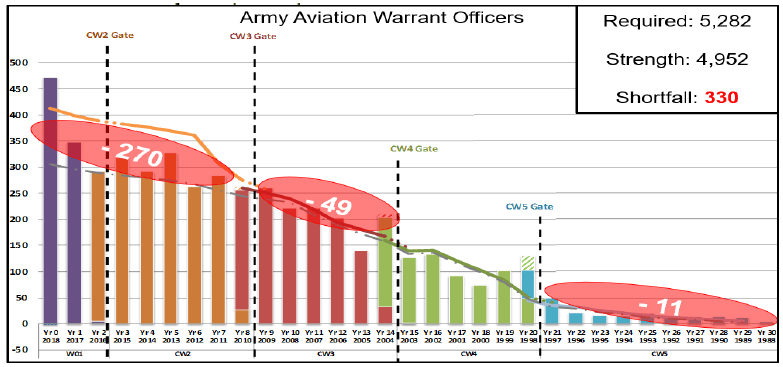

The report included a figure showing that the Army faced a shortfall of 330 warrant officers—who comprise 70 percent of the Army’s pilot ranks.

Active component warrant officer strength, as of October 1, 2018 (Source: Report to Congressional Armed Services Committees on Initiatives for Mitigating Military Pilot Shortfalls)

Why the ADSO?

Two main variables affect pilot strength in the military: production and retention. Of the two, retention is the variable that should be targeted. The congressional study on pilot retention noted, “One of the most important variables in meeting pilot requirements is the retention rate, as this is used to estimate what level of new pilot production is needed.”

Over the last few years, Army senior leaders took steps to address the pilot retention challenge. The Army increased monthly pilot pay from a maximum of $850 per month to $1000 per month, offered $35,000 annual bonuses to qualified warrant officers who extend for three years, and reduced combined training center rotations to two per twelve-month period for each combat aviation brigade.

In the report provided to Congress, however, increasing the service obligation was not mentioned as a possible solution to pilot retention shortfalls. This may be because the Army has not undertaken the same in-depth approach to understanding this problem as other services. The DoD report to Congress included a description of Air Force efforts to assess the problem:

The Air Force gathered data on what drives separations from an October 2015 Fighter Pilot Retention “Air Force Smart Operations for the 21st century” event, the 2015 Air Force Exit and Retention surveys, the August 2017 Dedicated Aircrew Retention Teaming Summit, and a series of three aircrew retention crowdsourcing surveys sent to 9,000 aircrew members that culminated in March 2018.

The Army, by contrast, could only say that “Army senior leaders recognize there are growing civilian opportunities for Army pilots. As a result, the US Army Aviation Center of Excellence initiated a survey to better inform future incentive and quality of life programs designed to increase retention.”

The Army’s blind spot with retention data is further highlighted by comments made by Brig. Gen. Michael McCurry, the director of Army aviation for the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff G-3/5/7, who said in September, “One question I often get asked is, are the airlines impacting your shortfall? Well, the short answer is, we don’t know. We don’t have good measurements out there right now to tell us why an aviator is getting out of the force.” Without useful data, the Army cannot implement targeted retention solutions.

Increasing the ADSO, though, does not require data—it is guaranteed to increase retention. It is the cheapest method for increasing retention rates, delivers a long-term investment in human capital, and provides a more predictable model for pilot production requirements. But at what cost?

The Problems with the ADSO

Traditionally, the Army has not struggled to recruit pilots. In the same discussion about retention data, Brig. Gen. McCurry also said, “People still want to fly. Our young NCOs want to become warrant officers and get out and fly. So the recruitment piece has not historically been our challenge, it has been capacity and production.” But what if the new ADSO invalidates this assumption?

This ADSO will likely cause a sharp decline in recruiting among cadets selecting their branches and enlisted soldiers and civilians interested in becoming Army pilots. A reduction in accessions will turn a long-term solution into a short-term problem.

Cadets, who have not experienced the Army for even one day as an officer, are now asked to commit up to eleven years for the opportunity to fly for six years—if they are lucky—while spending the rest of that time on staff, in professional military education, or in broadening assignments. Furthermore, for cadets who may want to pursue a civilian career after a stint in the Army, the opportunity costs are higher the longer they stay. These cadets may not be willing to forgo an extra four years of civilian work experience to serve as aviation officers.

The impact on warrant officers may be as severe as the impact on would-be aviation lieutenants. After all, it is the warrant officer exodus to the airlines that has driven the Army’s pilot retention focus. Prospective warrant officers can see that the Army is having trouble retaining pilots, and they can also see that increasing the service obligation by four years works against their best interests. If pilots today are so unhappy that they are leaving in numbers higher than expected, why would prospective pilots accept a much longer service obligation for that same experience?

There are also discussions within the Army aviation community of additional changes that would make becoming a warrant officer even less appealing. Although neither has been officially announced, the Army is rumored to be considering two proposals: a provisional status for warrant officer candidates until they graduate flight school and an increase in time-in-grade to make chief warrant officer 2.

Proponents of the new ADSO have suggested that the Army is catching up with the Air Force and the Navy by matching its pilot obligation with theirs. However, Army aviation should not be compared with the other military branches—not least because of the widely varying costs of producing pilots. The Government Accountability Office reported, for example, that it can take two years and three to eleven million dollars to produce a mission-ready fighter pilot. These figures do not include initial training—they solely account for the time and cost associated with the platform-specific training. For the Army, the costs are much cheaper. To create a mission-ready helicopter pilot, the Army invests between six hundred thousand and one million dollars during approximately one year of flight training.

Another disparity is the pay inequality between the military’s pilots. Again, 70 percent of Army pilots are warrant officers, while Air Force pilots are all officers. A chief warrant officer 3 with eight years of service earns $5093.70 per month, whereas a captain with eight years of service earns $6435.00 per month, a difference of $1,341.30 in favor of non-Army pilots. The disparity grows as pilots continue service, with a difference of $1,560.80 per month in favor of a major with fourteen years of service compared to a chief warrant officer 4 with fourteen years of service.

The Way Forward

While the ADSO goes into effect in October, its effect on retention won’t be felt for at least six years after the first ten-year ADSO class graduates—likely not until late 2027. Unfortunately, it probably won’t exist long enough for it to achieve the desired effects.

The severity of the decline in recruiting will be unknown until the recruiting data comes in from the first affected class of cadets and warrant officer candidates. But if online discussions are any indication, this ADSO will turn away a lot of prospective pilots. If retention suffers too much, the Army will face a pilot production shortfall that will add to the existing shortage.

If the Army rescinds this ADSO and reverts to the original six-year obligation, it will have six years to develop solutions to increase retention. The first step the Army must take is to implement exit surveys for pilots to determine why they are leaving. With this data, the Army can tailor solutions to address the issues that cause pilots to leave.

Furthermore, the Army should implement quality of life and quality of service surveys for every pilot who remains. Exit surveys are important, but those only capture the opinion of those whom the Army has already lost. The Army must also capture the opinions of those it can still retain.

Lasting solutions must come in the form of quality of life and quality of service improvements. With survey data in hand, the Army will likely find that it needs to continue to invest in its aircraft fleet to ensure pilots receive adequate flight hours to remain proficient. It must continue to remove burdens that plague the warrant officer community, such as non-pilot-related duties and frequent deployments to combat training centers. And finally, the Army will likely find that it should increase flight pay beyond what has already been offered. A RAND Corporation study found that even $35,000 a year would not be sufficient to stem the flow of Air Force pilots—the study concluded a bonus cap between $38,500 and $62,500 would be necessary to make a meaningful impact.

The future of Army aviation depends on retaining the pilots in whom it invests so much. However, increasing the service obligation of new pilots is the wrong course of action. It involves no effort to understand the underlying factors that cause Army pilots to depart and is nothing more than a surface-level solution to a fundamental problem. By collecting data and then improving quality of life and quality of service with targeted retention initiatives, the Army will not just increase retention—the positive changes will increase the appeal of serving as a pilot in the Army, and recruiting will increase as well.

Brennan Randel is a captain in the United States Army and is the former commander of Alpha Company, 4-2 Attack Battalion stationed at Camp Humphreys, South Korea. He is the author of the jumo brief, a free weekly newsletter for Army leaders.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Scott Tant, US Army