Harlan K. Ullman, Anatomy of Failure: Why America Loses Every War It Starts (Naval Institute Press, 2017)

The subtitle of this book raises a question that more Americans should ask: If the United States is the supremely powerful nation we believe it is, and if our armed forces are as great as we tell ourselves they are, why have our wars in the last half-century not been more successful?

In Anatomy of Failure, Harlan K. Ullman documents a long line of strategic failures from Vietnam, where he served as a young Navy officer, down to today’s wars in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and other places threatened by the Islamic State or other dangerous jihadist insurgencies. His verdict on the consistent ineffectiveness of US military efforts over those decades is convincing. His analysis of the causes and his recommendations for reform are somewhat less so, not so much because specific arguments are incorrect but because he does not address a number of crucial issues.

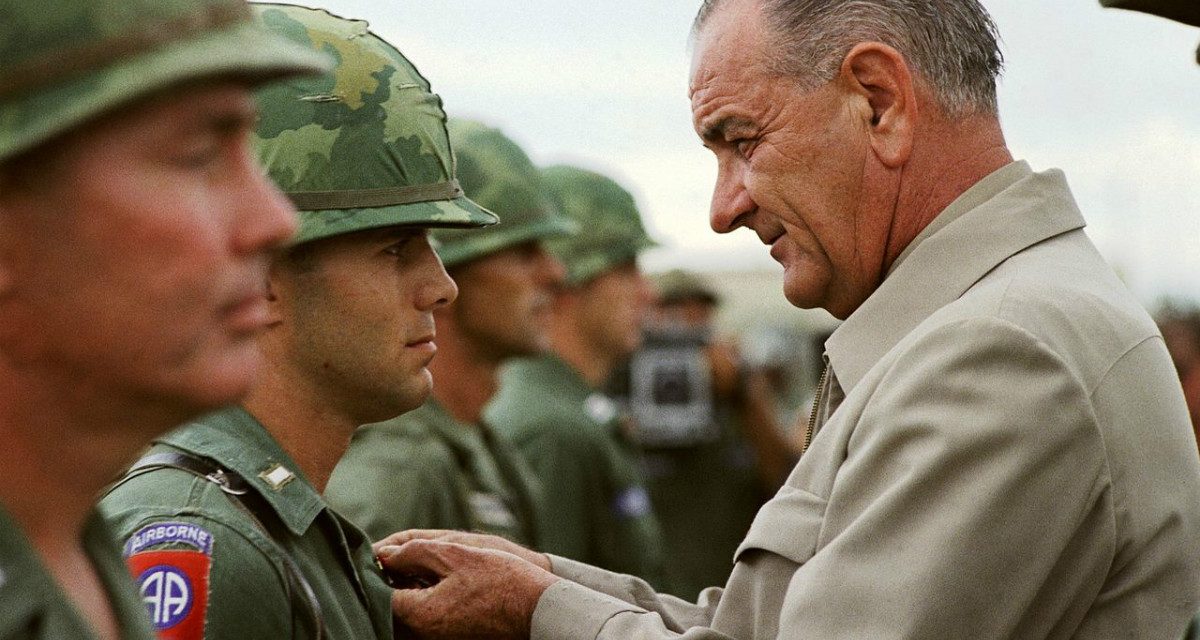

Ullman, who (as he repeatedly reminds us) has been a high-level adviser on national security matters in several administrations, concentrates almost entirely on strategic mistakes in the White House, rather than on the battlefields or in the US military leadership. In successive chapters he examines presidential policymaking and use-of-force decisions in every administration from John F. Kennedy’s to the early weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency. In keeping with that limited focus, he holds presidents and their national security teams all but exclusively to blame for the lack of military success.

Ullman’s specific critiques are on the whole well-reasoned and admirably free of partisan bias, and presidents are certainly responsible for the outcomes of their policies. So the conclusion as stated in his book is not wrong. It is, however, only one piece of a much larger puzzle, and Ullman gives surprisingly little attention—or none at all—to other key pieces. While criticizing presidents for not knowing enough or thinking clearly enough about military realities, for example, he says very little about the quality of advice those presidents have received from their military commanders.

Other relevant questions get similarly short shrift. Ullman gives hardly any meaningful attention to questions of US military practice and theory, or how America’s armed forces have actually performed in the wars they have been sent to fight. For example, though changing concepts of counterinsurgency strategy have been a central issue for military leaders during years of engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan, that subject gets only the barest mention, without details or analysis, in the book. Nor is there any discussion of US military aid programs, and why American resources and advisers have so consistently failed to make local governments and security forces more effective in the fight against a common enemy.

That last omission reflects the most serious gap in Ullman’s analysis. The weakness of local allies is arguably the most important reason by far for the lack of success in American wars from Vietnam on. But Ullman gives no indication that he has given any thought to that issue. Nowhere in the book does he ask or try to explain why Afghan and Iraqi security forces are not better than they are after years of US training and billions of dollars in military supplies and equipment. Nor does he have anything to say about issues such as corruption, which seriously undermines military performance, poisons relations between the security forces and civilians, and corrodes public trust and support for the government and its institutions—all of those greatly and sometimes fatally damaging to counterinsurgency efforts. Despite many painful lessons on corruption’s destructive effect, US officials in successive wars have not come up with an effective anticorruption strategy, a failure that surely warranted attention in this book.

Time and again, in his case studies of particular conflicts and in his concluding argument and recommendations, Ullman emphasizes the importance of good intelligence, which he defines as “extensive knowledge and understanding of the enemy at all levels.” That’s the classic concept, but—though there’s no evidence Ullman considered this—perhaps out of date, as shown in the very wars he examines in his book. Almost certainly, the most damaging intelligence failure in Vietnam and Iraq and Afghanistan was not that we didn’t know our enemy, but that we didn’t know our friend. In all those conflicts US policymakers and military commanders regularly overestimated our allies’ capabilities and underestimated their weaknesses, leading to highly unrealistic assessments of what US interventions could accomplish.

In calling attention to a significant issue that US leaders and the American public need to face much more squarely, Anatomy of Failure makes a meaningful contribution to an important national discussion. Turning a wider lens on its subject, and taking more critical looks at conventional wisdom and inside-the-bubble assumptions, could have made that contribution even more valuable.

When was the last time the US won a real war? How about World War 2. And what did the US do differently in that war? It killed civilians, lots of civilians.

If you want to win wars, then you have to defeat both the enemy military and supporting civilian population. You have to keep killing both until they publicly acknowledge defeat.

Of course, killing civilians is a war crime. So there is no hope of winning wars in the future.