What is Army Doctrine? It’s a simple question. But I’ve asked cadets, peers, and a few willing superiors and the range of their answers is surprisingly wide. I also hear the term “doctrine” being used in as many different ways as the “hooah,” which depending on the context, tone and inflection of voice, and recipient can mean everything from “yes,” “tough,” “let’s go,” to “I really don’t like you.” This should not be the case with doctrine and we (Army Professionals) should resolve this lack of clarity.

A quote attributed to a German officer during World War II shows the persistence of the Army’s ambivalence towards doctrine: “One of the serious problems in planning the fight against American doctrine, is that the Americans do not read their manuals, nor do they feel any obligation to follow their doctrine.” While the lack of studying our own doctrine is a separate topic, the quote opens the conversation to the importance of doctrine in our professional military education.

The first step in learning doctrine should be understanding what it is. To find the “official” definition of doctrine, I turned to doctrine (pun intended). Interestingly, there was an appendix titled “The Role of Doctrine” in the 2008 edition of Field Manual 3-0: Operations. The manual that replaced it includes only two paragraphs on the role of doctrine and the remainder of the material was moved to a new 64 page Doctrine Primer (ADP 1-01) that greatly expands the topic. The remainder of this article relies heavily on the short but detailed definition of the role and components of doctrine in the 2008 FM 3-0.

As a military term, Army doctrine is defined as the fundamental principles by which the military forces or elements thereof guide their actions in support of national objectives.

But doctrine is more than just principles. It is a body of thought on how Army forces intend to operate as part of a joint force and a statement of how the Army intends to fight. It establishes a common frame of reference including intellectual tools that Army leaders use to solve military problems. It is supposed to focus on how to think—not what to think.

Fredrick the Great once said “War is not an affair of chance. A great deal of knowledge, study, and meditation is necessary to conduct it well.”

Doctrine is frequently discussed in a negative way. A quote attributed to Marine General Jim Mattis is illustrative of this view: “Doctrine is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” But quotes like these view doctrine as a set of rules that soldiers must follow. This again is a misunderstanding of what doctrine actually consist of.

According to the old FM 3-0, doctrine consists of a) fundamental principles, b) tactics, techniques, and procedures, and c) terms and symbols.

First and foremost, doctrine provides fundamental principles. These principles reflect the Army’s views about what works in war, based on its past experience. They are principles that have been learned through battles and wars that have been successful under many conditions such as the principles of fire and maneuver or the principles of joint operations. Importantly, doctrine is not always prescriptive, but it is authoritative and a starting point in addressing new problems.

Principles are not supposed to be checklists or constraining sets of rules. They are meant to foster the initiative needed for soldiers to be adaptive, creative problem solvers. They provide a basis for incorporating new ideas, technologies, and organizational designs.

Secondly, doctrine consists of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). TTPs incorporate the Army’s evolving knowledge and experience. They support and implement fundamental principles, linking them with associated applications. The “how to” of tactics, techniques, and procedures includes descriptive and prescriptive methods and processes.

Tactics are the employment and ordered arrangement of forces in relation to each other.

Techniques are non-prescriptive ways or methods used to perform missions, functions, or tasks. They are the primary means of conveying the lessons learned that units gain in operations.

Procedures are standard, detailed steps that prescribe how to perform specific tasks. They normally consist of a series of steps in a set order. Procedures are prescriptive; regardless of circumstances, they are executed in the same manner. They are often based on equipment and are specific to particular types of units. A common set of procedures in the army include individual unit Standard Operating Procedure (SOPs).

Finally, doctrine provides a common language for military professionals to communicate with one another. This is particularly important under fire when information must be quickly and accurately transferred—and universally understood.

Terms with commonly understood definitions comprise a major part of the Army’s common language. When a mission is given to destroy, clear, or secure an objective there will should be shared understanding by all on the task to be completed. And yes, doctrine includes our love of acronyms so that we can transfer a lot of information quickly. “SP the AA NLT 1900 IOT cross the LD at 1930.” – got it?

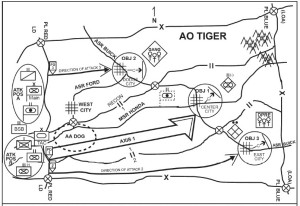

Military symbols are our way of providing common graphical understanding of a myriad of information and provide another way to quickly transfer information.

Establishing and using words and symbols with common military meanings enhances communication. It makes a common understanding of doctrine possible. Doctrine provides the ability to take a sketch like the figure below to transfer a massive amount of information. It enables soldiers to quickly identify the units involved, the main effort, all the missions, the exact tasks to be completed and much more.

The importance of this common language cannot be overstated. It allows people from completely different backgrounds (social, regional, commissioning sources, etc.) to quickly learn a universal language. It enables the Army to communicate quickly even when there is a language barrier such as military international, multinational, non-government partnerships.

So the next time someone uses “doctrine” in a negative context, or states “that’s not doctrine,” push back and tell them they are wrong. Fredrick the Great once said, “War is not an affair of chance. A great deal of knowledge, study, and meditation is necessary to conduct it well.” Doctrine is the collective wisdom of our Army and the common language of our profession. It provides the lessons from generations of soldiers learned during hard fought battles, campaigns, and wars. Challenge the naysayers who might think they are smart enough to win the next war on the basis of their experience alone. Encourage all to take advantage of the tools doctrine provides our force.

[Correction: This article was amended to reflect reader feedback reference ADP 1-01]

Great Read!!!

CPT D.

A very good read and prompt for more discussion beyond references. Doctrine must be taught but should be considered as a starting point, not a defined and constricted space to initiate military operations. The challenge here is in providing forces an agile and adaptive perspective in employing principles/logic/tools of the evolving battlefield – in referencing this essay “Principles are not supposed to be checklists or constraining sets of rules” is exactly where current operations and legacy approaches often diverge — and where the following “…meant to foster the initiative needed for soldiers to be adaptive, creative problem solvers” create friction” is an understatement – attempting to “… provide a basis for incorporating new ideas, technologies, and organizational designs” should be a goal and not be the obstacle – maneuver warfare, limited warfare, light forces… are constantly derided for being at odds with traditional employment and force structure, and are often given a label or thought of as a temporary condition which will soon pass so that staffs can return to core priorities. While the definition of doctrine is pure and simple, it is often referenced and derided in the classroom to be associated with Napoleonic encampments or WW1 trench warfare, as a lack of leadership perspective to a revised battlefield or adaptive enemy and thus ignored. If I received a tasker to revise/update Army doctrine, I would imagine the fully staffed and coordinated version might emerge in 2 to 3 years, thus confirming the perception that published doctrine is not relevant to the current operational field of view.

Good article John. While I agree that doctrine is important and everyone should read and understand its application, there is room for creativity. Doctrine provides the foundation, the professional language that we must all speak to accomplish our mission. The problem is becoming too tied to what doctrine says and this tends to stifle creative thought. Use doctrine to start the conversation and start a plan, but allow people the freedom to deviate or go against doctrine(when needed). To deviate or go against requires you to understand doctrine and it’s application, but not be so tied to doctrine you stifle creativity and initiative.

But Frederick the Great also said, “If my soldiers were to begin to think, not one of them would remain in the army.”

As a long term ‘Doctrine Guy’, I’d add this bit of insight. Doctrine allows ‘new guys’ to benefit from the experiences of ‘old guys’, without actually having face to face discussions. Here’s what I mean…doctrine is simply the codified ‘best practices’ of someone before your time having figured out a way to do something, that worked. So, if you have no experience at doing whatever your military task is, then read the doctrine, understand it, and ‘bingo’…you now have one way to get that job done. If you have been at the job for longer than one day, then you may have seen other ways to do the job, that also achieve success. Great. However, being on the job for more than one day, you may not have found another way to get the job done. That is also ‘Great’. As US military personnel, we are all expected to use our brains to solve problems. Sometimes the solutions will be based on personal experience, sometimes the solutions will be ones found in doctrine…either way, the best ‘problem solver’ will conduct an honest assessment of the situation (METT-TC), then use all their available resouces to solve the problem.

As I interpret Gen Mattis' quote ("Doctrine is the last refuge of the unimaginative"), his comment is not to disparage doctrine, but merely to indicate that those who are unimaginative think no further than what is clearly stated in doctrine. Doctrine provides not only a common language from which we can express complex ideas, but it also serves as a point of departure to more imaginative concepts of how to conduct military operations. Doctrine is frequently derived from experiences (good or bad), but just like any financial planner will tell you, past experiences do not guarantee future performance. The world is constantly changing and modern militraries modify their doctrine as necessary to remain relevant and effective. The more fundamental the doctrinal principle, the more enduring it becomes, while doctrine that is based on specific capabilities or tools may be quickly overcome by events. .

Couldn’t of said it better myself

DAV Ssg last conflict Iraqi Freedom 2003-2005

in fact the army doctrine was intended for prospective army or only candidates who would carry out war, whether the doctrine could always be successfully carried out. if the doctrine fails, what impact will it have?

Army Doctrine: Never force a safeguard.

Command Decisions(a privilege of and by rank): How individuals achieve doctrinal goals, by using one's own personal initiatives, thru free will. (Hint: In the words of the great Alexander "fortune favors the bold,"(male role model), and Jovanna de Arco, to "strike, strike boldly," (female role model), I use successful role models here. Or in the words of General Patton, paraphrasing the great Frederick, paraphrasing the Grand Conde of France, in French, "L'audace l'audace toujours l'audace,"(Attack, attack, and again attack.)

Why are tactics and techniques differentiated? Techniques seems like a more descriptive element of tactics. Is a technique a sub-component of a tactic? If tactics are ordered arrangements of forces but techniques are methods used to perform tasks, then wouldn't a simple formation be a tactic yet the implementation of that formation through tasks be a technique? This seems confusing and counter-intuitive. Can you give an example using the same scenario/mission?

in fact the army doctrine was intended for prospective army or only candidates who would carry out war, whether the doctrine could always be successfully carried out. if the doctrine fails, what impact will it have?

No. You missed the point of total annihalation of ones enemies. Your description merely points out the fundamentals of an over arching doctrine. Please review Airland battle doctrine, circa 1985. That is when the USArmy had figured it out, in concert with our Constitution.

FM 3-0: That monster was my most hated Army manual