In spite of the sight of the Stars and Bars flying from the radio masts of occasional automobiles coming out of Dixie, few fair-minded men can feel today that the issues which divided the North and South in 1861 have any real meaning to our present generation.

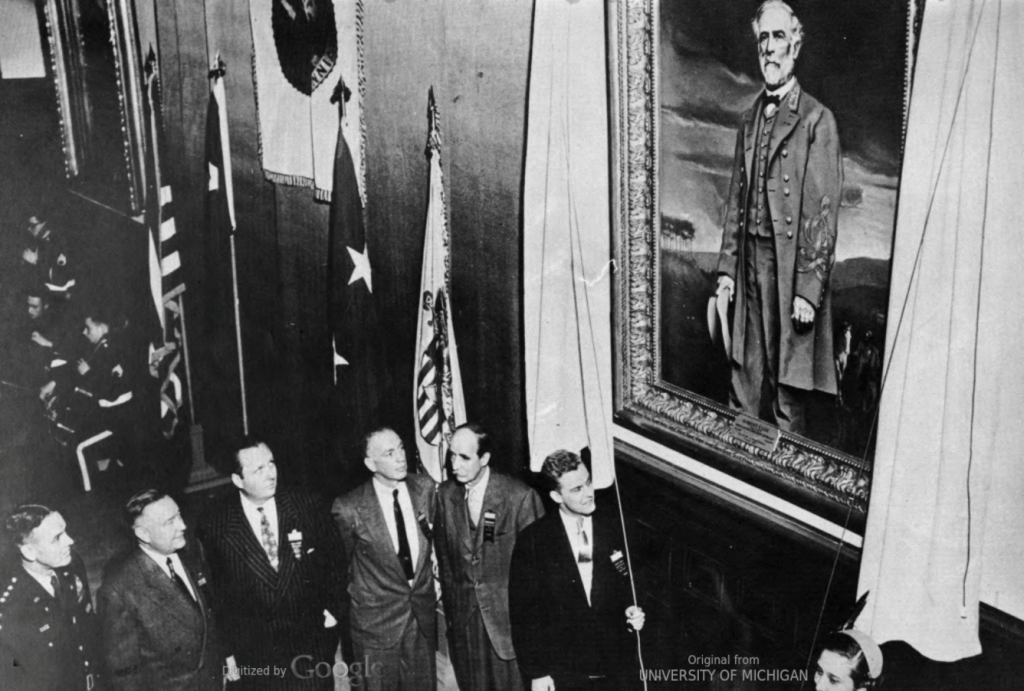

Those were the words spoken by famous World War II general Maxwell Taylor in 1952, at the dedication of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s portrait in the West Point library. This portrait has since become the topic of controversy from many who question the reverence for Lee at West Point in the form of a barracks, a gate, and multiple paintings.

Articles exploring this veneration and petitions calling for the removal of displays of Lee at West Point often fall short in addressing exactly how the Confederate leader became ingrained in academy culture. Lee’s return to a place of honor at West Point occurred as a result of a reconciliation process that downplayed the Confederacy’s treason as the primary transgression for which southern officers required forgiveness, papered over the issue of slavery, and ignored the underrepresented black officers of the US Army. The reverence shown, though, is no longer unchallenged by the diverse, twenty-first-century officer corps, and as a result, West Point now faces a decision: What should it do with displays of Lee’s person and his name? And more broadly, what place should this controversial figure—and former academy superintendent—occupy at the academy?

At the turn of the twentieth century, the institutional narrative at West Point about the Union cause was still focused on two major points: the preservation of the Union in the face of secession and the freedom of slaves. During this period, two construction projects at West Point memorialized the Civil War—the Battle Monument, a towering column at Trophy Point that was completed in 1897, and Cullum Hall, a building completed in 1900.

The Battle Monument was erected to memorialize all Union Army regulars who were killed during the Civil War. According to its official history published in 1898, the monument commemorates the souls who “freed a race and welded a nation.” Supreme Court Justice David Brewer, who spoke at the dedication ceremony, likewise described these two causes as the primary reasons that the Union’s struggle should be remembered by cadets. The monument itself still contains an inscription on its shaft calling the Civil War the “War of Rebellion” to bring attention to the treasonous actions of the Confederacy.

Cullum Hall, where Lee’s name first started to appear after the Civil War, was completed to serve as a memorial hall for West Point graduates who distinguished themselves in the military profession. The building’s deceased benefactor and Union veteran, Maj. Gen. George Cullum, left the funds for its construction in his will, and the decision as to who was worthy of memorialization in the building would be subject to a vote of West Point’s academic board. Robert E. Lee’s name was placed in this building on a bronze plaque that named the past superintendents of the academy and the years they served in the role. The decision to include Lee’s name seems to have little to do with his leadership of the Confederate Army, but was treated as a matter of historical record.

Only two years later in 1902, dozens of both Confederate and Union West Point graduates attended the one hundredth anniversary celebrations of the academy’s founding. The festivities included a speech by Brig. Gen. Edward P. Alexander, a highly influential Confederate officer who used the spotlight to catalyze the reconciliation process between white Union and Confederate graduates. Alexander’s address was steeped in “Lost Cause” rhetoric that glorified the right of states to secede. In the spirit of reconciliation however, Alexander admitted that “it was best for the South that the cause was lost,” since he viewed the strength of United States in 1902 as rivaling that of other major world powers. Finally, Alexander spoke directly of the pride “heroes of future wars” would feel toward the accomplishments of Confederate graduates, predicting those heroes would “emulate our Lees and Jacksons.” Notably, Alexander mentioned nothing of the institution of slavery, which the Confederacy fought to defend and Union graduates died to erase.

From that period forward, the narrative at West Point regarding its Confederate graduates markedly changed. Taking Alexander’s stirring words to heart, the Corps of Cadets began to forgive Confederate graduates for seceding and glorified their military accomplishments. Talk of slavery became rare—much like black membership in the Corps of Cadets during the first half of the twentieth century—and relics of Robert E. Lee appeared slowly at the academy with the support of southern interest groups.

In 1930, the United Daughters of the Confederacy—known for its financing of Confederate memorials in the early 1900s and pushing the “Lost Cause” narrative—reached out to West Point officials offering to donate a portrait of Robert E. Lee to be displayed in the Mess Hall next to portraits of other West Point superintendents. The organization hoped to feature Lee in his gray Confederate uniform, but the academy, perhaps still wary of Lee’s treasonous legacy, requested that the portrait feature Lee in the blue US Army uniform he donned as superintendent. That version of the portrait is still on display in the Mess Hall in an unremarkable fashion next to the portraits of every West Point superintendent.

The following year, the United Daughters of the Confederacy made another offer to West Point, this time to sponsor a mathematics award dedicated to Lee, who was known for his mathematical acumen as a cadet. This memorial award was sanctioned by the academy and was given until 2018 in the form of a saber, but it ceased to be sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1993, after curriculum changes meant it would no longer be presented during convocation.

Meanwhile, as the United Daughters of the Confederacy slipped Lee back into the academy’s memory and the white officer corps reconciled old differences, African-American cadets were subjugated to harsh and unfair treatment by academy officials and fellow white cadets. The best example is Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.—the academy’s fourth black graduate in the seven decades after slavery ended—who is the namesake of the academy’s newest barracks construction. In the 1930s he was given a solo room assignment and no other cadets would speak to him during his entire four years as a cadet (an act known as “silencing” typically used against cadets who were considered dishonorable). Davis graduated in the top 15 percent of the Class of 1936, but was denied entry into the Army Air Corps to maintain segregation policies. Davis continued to be silenced by several classmates and other officers for years after commissioning. For decades, Davis’s classmates and West Point leadership denied publicly that Davis was silenced, while several others wrote him letters of apology in private. His experience stands in stark contrast to that of white cadets who pushed forward with reconciliation in the same era as the institutional memory of Confederate leaders grew more positive.

Robert E. Lee’s validation as a revered figure in West Point lore was cemented on the one hundredth anniversary of his selection as superintendent and during the 150th anniversary celebration of West Point’s founding. On January 19, 1952, a massive portrait of Robert E. Lee—in full Confederate gray uniform, with a slave guiding his horse behind him—was donated to the West Point library.

Gen. Maxwell Taylor and other dignitaries and guests at the unveiling of the portrait of Robert E. Lee at West Point on January 19, 1952. (Source: The Sesquicentennial of the United States Military Academy)

The portrait’s unveiling was the occasion when Gen. Maxwell Taylor claimed that “few fair-minded men can feel today that the issues which divided the North and South in 1861 have any real meaning to our present generation.” He spoke these words only a month after the Army decided to pursue full desegregation and three years before both Emmett Till’s murder and Rosa Parks’s arrest. Desegregation nationwide still had far to go in 1952. This willful ignorance of the black experience in American history—including in American military history—was critical to the lionization of Confederate heroes and reconciliation with white southern officers. Without it, cadets and officers alike would be forced to grapple with the fact that men like Robert E. Lee betrayed their country for the right to continue owning and subjugating an entire race of people they thought inferior.

Retired Gen. David Petraeus, a West Point graduate, recently described his alma mater’s problematic association with Lee, including a barracks built, he notes, in the 1960s. While it’s true the barracks in question was completed in 1962, at the height of the civil rights movement, it was initially named “New South Barracks.” It was not named in honor of Lee until 1970, when several buildings at the academy received the names of past graduates. Lee Gate received its name in the late 1940s, when the names of all entrances to the post were changed. In broad historical context, the how, when, and why of the naming convention for Lee Barracks or Lee Gate is relatively benign in comparison to the dedication of Lee’s portrait to the West Point library. An entire committee of powerful southern financiers was dedicated to bringing back Lee’s likeness as a Confederate champion in 1952. By the time Lee Barracks was named, the view of the Civil War at West Point had already undergone a complete metamorphosis.

So, what should West Point do about its Robert E. Lee problem? We believe the solution to this complex issue is simple: Lee should be remembered, but not honored. That starts by admitting that West Point and Army leaders got it wrong in 1952. The issues of the Civil War did have a “real meaning” to the “present generation” when Taylor spoke at the unveiling of Lee’s Confederate portrait, and they have a very real meaning to our generation today. Here are our recommendations:

- Lee’s name should remain in Cullum Hall. Lee was the superintendent of West Point and his positive contributions to the academy in this regard cannot and should not be ignored. In the same vein, Lee’s portrait in the mess hall showing him in his blue US Army dress uniform as superintendent should remain as a matter of historical record.

- Lee’s Confederate portrait and any others like it should be removed and placed in the West Point museum or visitors center with appropriate historical context and background.

- Lee Barracks and Lee Gate should be renamed. Lee’s name on these facilities became an everyday testimony to the newly reverential treatment of Confederates at the academy. This encourages a revisionist history that elevates Confederates’ positive characteristics and ignores their treason and support for the institution of slavery.

Some argue that removing such symbols is tantamount to erasing history and calls for founders like George Washington to be “canceled.” We categorically reject this straw-man argument. Robert E. Lee was not just a racist and a slave owner. He chose to betray his country in the defense of his right to subjugate the black race, which now comprises a significant portion of the Army and officer corps. The leadership who saw fit to prop up Robert E. Lee as a revered figure in 1952 did so by accepting a comfortable, watered-down, and cherry-picked revisionist history. Today, history classes at the academy fully embrace the correct notion that preserving the nation’s unity and ending slavery were the defining features of the Union cause, and cadets learn about both the military skill and ideological wrongdoings of Lee and his Confederate comrades. Cadets also learn about hundreds of West Point graduates whose accomplishments are worthy of honor, respect, and reverence. Although they learn about Lee, he is not one of those deserving of such reverence by the future officer corps.

West Point seeks to educate, train, and inspire future leaders in the US Army. The Corps of Cadets is the most diverse in the school’s history and West Point needs to ensure cadets can continue to be inspired by graduates the academy sought to elevate in a bygone era. The school has so far avoided this question of Robert E. Lee, looking to the US Army for guidance. But as West Point tells many of its growing leaders, there is nothing wrong with offering a recommendation to one’s superiors. The school has a responsibility to its cadets, and we hope West Point will do what it expects of its graduates—lead.

Capt. Jimmy Byrn graduated from the United States Military Academy in 2012 with a BS in Military History. During his time on active duty, he deployed to Poland, Bulgaria, and Kosovo in support of NATO Operations Atlantic Resolve and Joint Guardian. He is currently an incoming JD candidate at Yale Law School.

Capt. Gabe Royal graduated from the United States Military Academy in 2012 with a BS in US History and American Politics. He is a veteran of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts and an incoming PhD student at the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Administration at George Washington University, and will teach at West Point upon completion of his degree.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect that the Department of Mathematics ceased presenting the award named for Robert E. Lee in 2018, and that the United Daughters of the Confederacy stopped sponsoring the award in 1993 after curriculum changes meant it was given annually to an underclassman and thus not presented during West Point’s convocation. The organization elected instead to transfer their donation to a different department to sponsor an award that would be included in the convocation ceremony.

Image credit: Michelle Eberhart, US Army