Among those of us who wear a US military uniform, many have witnessed or experienced extraordinary, and potentially traumatic things. Some have watched friends die. Some have seen war’s indescribable destruction up close. Some have killed.

We cannot change the past, and we cannot just make the painful memories of such things vanish in the present. There is no guarantee we will not face similar hardships in the future. But there are many who have endured the struggle in some fashion who can relate to us. It’s important for each of us to understand that we are not alone. And it’s especially important to do something that, for many of us, feels overwhelmingly difficult—talk about our experiences, open up about our struggles, and help each other.

You may be a future leader who could go through similar experiences to those I have endured, or you might be a veteran soldier who has been through what I have experienced (or even worse). You could be a civilian seeking to better understand what the warriors of your country saw and what they now must cope with. You might be a family member or friend who understands all too well what your loved one has gone through (and still may be going through). Perhaps you have dealt first-hand with a rocky homecoming experience and the post-traumatic stress disorder and its symptoms that never seem to go away in someone who you care deeply about. In any of these cases, I hope sharing my experiences will help.

Talking about what we have gone through is important in its own right—we owe it to those who have volunteered to serve, and to ourselves, to focus on healing. But in the unlikely event that anyone reading this doubts its importance, it is also an issue deeply tied to military effectiveness. It is no secret that the number one priority of the Army is readiness, but how can soldiers, families, and units be ready for anything when so many have not addressed one of the largest challenges to readiness—PTSD?

Before I share some of my experiences, there are resources, tools, and options available to cope with such trauma that I recommend finding. Tanisha Fazal’s historical examination of PTSD and veterans’ benefits is certainly a must-read and a great starting point. Additionally, anyone can access the US Department of Veterans Affairs to develop a further understanding of PTSD, to include treatments, starting with the basics, medications, and types of therapy. The department’s National Center for PTSD includes this and more. Although tragedies still occur, the assets available to us have increased, and the attitudes about treatment have improved. I have certainly noticed a positive difference in mindsets about coming forward when you need help, especially compared to when I first joined the Army in the mid-nineties. Trained by professionals who learned under Vietnam veterans, it was very unpopular to talk about trauma, even seen as a weakness. Thankfully, we’ve come a long way.

Even in the early years of Operation Iraqi Freedom, though, there seemed to be a cultural aversion to admitting to struggling with what we experienced. When I returned from my first deployment in 2005 and underwent DoD’s newly mandated screening, called the Post Deployment Health Re-Assessment, there was a sense that many still saw the associated traumas of killing as a weakness. I still recall hearing some soldiers brag about answering a medical screener’s questions regarding feelings of killing with, “No, it didn’t bother me at all—I want to kill some more!” Many saw it as a sign of grit or toughness, a badge of honor that demonstrated fitness for the military profession. The response to seeing friends and comrades killed was often also wrapped in a layer of machismo. “Yeah it sucks, but hey, this is war,” many would say. We are all familiar with the imagery of the iceberg. Just like it was what lay beneath the water’s surface that sank the Titanic, underneath these layers of toughness that we manufactured to get by was what was most dangerous.

As many of us know, it is extremely difficult to solve a problem if we have not even identified that a problem exists. Once identified, we must then properly define the problem if we hope to seek and find the correct solutions or tools to fix it. As the old saying goes, “If all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.”

When I returned from that traumatic first deployment, I recall hitting the ground when a car or motorcycle backfired and driving on the interstate just wondering where the next bullet or roadside bomb would appear to wreck my world. I had a few disturbing dreams, and felt a bit odd around large crowds, but it seemed small at the time, and these seemed to fade over a year or so. Memories of firefights in Mosul on Veterans Day in 2004 occasionally intruded into my mind, as did other thoughts such as that of the death on December 21 of that year of my commander, Capt. Bill Jacobsen, in the Mosul dining facility suicide bombing. I would focus on the fact that I wasn’t able to save him or others we lost that day as I rushed into the chow hall immediately after the explosion.

It may not be logical to feel guilt for such things we could not have stopped, but it still came in waves. My own injuries from two massive explosions in Tal Afar in February and again in April 2005 were quite small compared to the “what if” scenarios I put myself through. What if my then soon-to-be-born daughter had to grow up without her dad? What about the Iraqi children who did grow up without one because my team and I could not save their dads we had trained in the Iraqi Army. But that began to fade with the passage of time, until just over a decade later. My 2009 deployment was largely without incident, yet when I began training in the 1st Security Force Assistance Brigade in 2017 to deploy to Afghanistan, that iceberg revealed just how deeply it sat beneath the water—ready to sink me. Flashbacks during training, irritability and apprehension at loud noises and large crowds, waking up to nightmares or an urgent need to check all door locks in the house, emotional numbness toward loved ones, and apathy toward favored activities—these were just the beginning.

One lesson I learned from my experience: you do not have to tough it out. Never in the twenty years I’d worked with or in the Army to that point did I believe I could come forward and say to my commander, “I don’t think I can do this job right now.” It would have been a career death knell, especially while in command. It is hard to determine which is (and was) more difficult—telling your boss you are not mentally fit to lead in combat or telling the soldiers you lead. But doing both is part of identifying the problem and to work toward solutions and strategies to overcome it. The unit chaplain and the military and family life counseling program offices were my next visits, and their services are not just for soldiers but families as well. The Army now has behavioral health specialist soldiers, but I personally saw one of DoD’s ten thousand civilian behavioral health providers for individual therapy, as most bases have several of them.

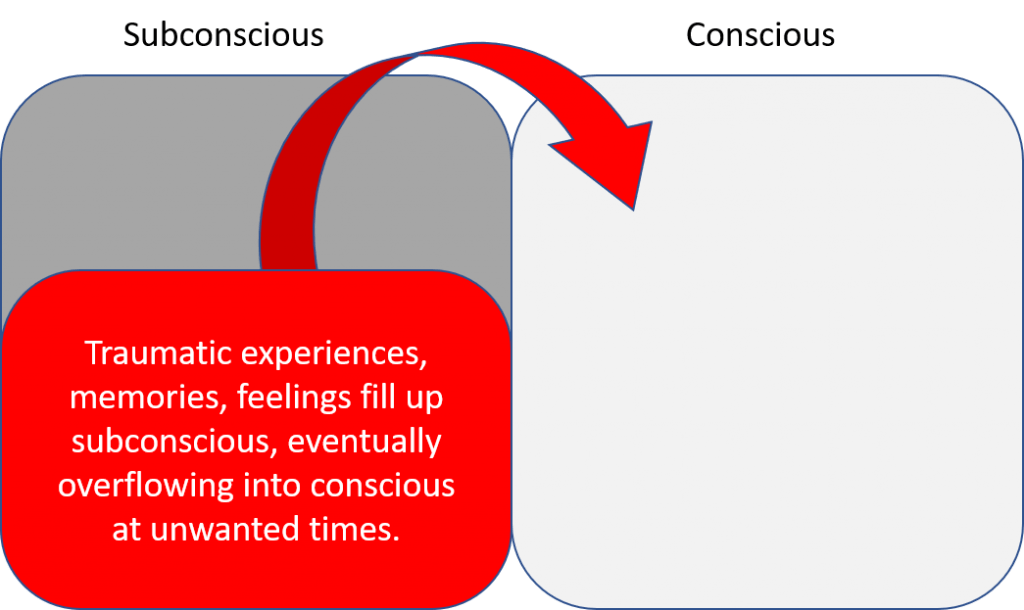

Every counselor and soldier who had been through therapy shared how important it is to talk about our trauma, allowing the memories and feelings to be brought from the subconscious to conscious parts of our minds in a controlled manner. If we do this, we can apply specific strategies to each symptom. This also prevents trauma symptoms from bottling up until they burst like a dam into our consciousness.

Any good strategy needs multiple ways to attack a problem, making the best use of available means (or resources). When preparing for a new job or a mission we seek all the expertise, training, and venues we can for success, and we should do the same for our mental health. The trained and educated counselor in my group therapy was a retired sergeant major with well over twenty years in service, five deployments, and his own share of PTSD experiences. I also signed up for a twelve-week combat trauma recovery class called REBOOT, which a co-worker told me about, then helped co-facilitate another one as a leader. I also sought counsel, prayer, and support from my family and the fellowship in my faith. The spiritual dimension is one of five dimensions of strength described in the Army regulation covering comprehensive soldier and family fitness, and while faith-based courses and sources might not be of interest to all, for those to whom they are these resources are another tool with which to find solutions.

As military members, we refuse to settle for defeat in other areas of our profession and our lives. We need to do the same for healing the invisible wounds of war. It starts with talking.

Matt Sacra is a US Army armor officer and instructor in the Defense and Strategic Studies Program at West Point.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Michael Eaddy (derived from video, adapted by MWI)