Editor’s note: Welcome to another installment of our weekly War Books series! The premise is simple and straightforward. We invite a participant to recommend five books and tell us what sets each one apart. War Books is a resource for MWI readers who want to learn more about important subjects related to modern war and are looking for books to add to their reading lists.

This week’s War Books installment explores what it means to be a veteran. There’s no single answer to that question—which means the books we read, as veterans, to process our military experiences and understand the way our military service shapes our identities vary widely. There isn’t a single set of books that could remotely cover such a subject, but as a starting point, last year we asked several MWI staff members to respond to the following prompt: What books, more than any others, speak to you as a veteran? Why? To mark Veterans Day, we’re republishing their responses this year.

Colonel Patrick Sullivan, MWI director and active duty Army officer

The Things They Carried, by Tim O’Brien

The Things They Carried is a collection of semiautobiographical short stories that recounts O’Brien’s experience as a draftee infantryman in Vietnam from 1969 until 1970. I first read it as an ROTC cadet at Duke University in the early 1990s as an assignment from one of my military science instructors, and it has stayed with me since. There is nothing quite like it in the Vietnam canon or other accounts of soldiering. O’Brien perfectly captures the full gamut of what one can feel and experience in combat, from the “truth is stranger than fiction” episodes of hilariously bad judgement that all soldiers can display, to the quiet moments of brotherhood, to the coping masked as morbid resignation, to the stupidities borne of alpha-male posturing, to the devastating pain of loss, and, finally, to the sobering realization that life goes on without you. O’Brien’s stories come fast and with an unpredictable tone, and you never quite figure out what O’Brien’s reality was and what is straight fiction, and how he might have blurred the lines between the two in a form of meta-commentary. That’s the point, however, because who knows with certainty the line between truth and fiction in the recounting of their own combat experiences? We are each our own unreliable narrators, after all. The Things They Carried will make you laugh and cry, deeply and in equal measure, but most importantly, it will make you reflect. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

John Spencer, chair of urban warfare studies and retired Army officer

Tribe, by Sebastian Junger

Junger discusses the complex topic of why soldiers miss war, why they miss the deep bonds and the sense of community—call it a tribe if you like, as Junger did—experienced by men and women who have served in the military and combat. Junger explores the the attributes, meaning, and norms of tribes, examines the issues soldiers have when returning from war or leaving military service and reentering society as civilians—a society that is increasingly divided and where a sense of community, tribe, and togetherness is often lacking.

Timothy Heck, former deputy editorial director and Marine Reserve officer

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, by Sloan Wilson

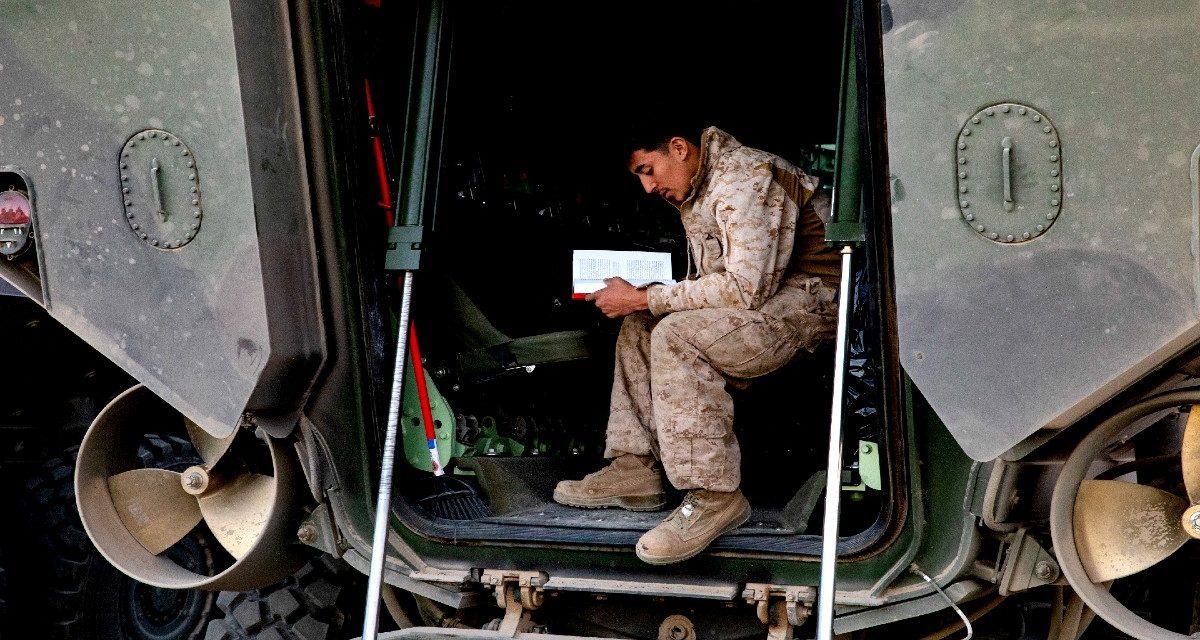

I first read The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit sitting atop the HESCO barriers of my small firebase in Fallujah waiting to do something. It was late 2007 and the war, by the time I showed up, was all but over in Anbar province. So, to fill the time while not working out or watching Lost, I read voraciously. Wilson’s story of a veteran trying to find meaning in his world resonated with me. Tom Rath’s changes and struggles were different than mine, but something connected me to him. How, after all, can someone ever be the same again after seeing the elephant?

Lieutenant Colonel Jeremy Fox, former MWI deputy director and active duty Army officer

The Art of Command, edited by Harry S. Laver & Jeffrey J. Matthews

This is an excellent read for leaders at all levels, leveraging lessons learned from influential military leaders over the past 250 years. The integrity of George Washington, the determination of Ulysses Grant, the followership of Colin Powell, and other leadership examples highlight the very best that our country has to offer and show aspiring leaders the standard of courage and perseverance to which we should all strive. This book serves as a terrific gift idea for newly minted officers and those about to assume the mantle of command.

The Servant as a Leader, by Robert Greenleaf

This is more of a pamphlet than a book, but its brevity belies its importance. It coined the term “servant leader”—which simply describes leaders who are empowered to help others. This book was especially impactful when I read it as a company commander charged with the morale and welfare of over a hundred soldiers and their families. Training warrior tasks, marksmanship, and battle drills is important, but soldiers cannot give their all unless they are cared for. By position and authority, leaders should remove obstacles, provide resources, and enable their subordinates so that the organization can execute at optimum capacity.

The Killer Angels: The Classic Novel of The Civil War, by Michael Shaara

A historical novel portraying the decisions and events leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg, this book describes the political pressure put on the field generals to achieve decisive victory. It also shows the softer side of leadership in action with the compassion and care of Longstreet and the heroism and the fortitude of Chamberlain’s bayonet charge. It brings the reader onto the battlefield, describing the sight, smell, and horror of the Civil War.

John Amble, editorial director and former Army officer

A Small Place in Italy, by Eric Newby

When I arrived in Afghanistan, I spent the first few days at Bagram Airfield. The very first morning, I walked out of the plywood hut—one among many that served as transient housing—and was stopped dead in my tracks by the beauty of the mountains beyond the base’s walls. They felt close enough to touch, and I thought immediately about what a draw this country should be for tourists from around the world—if only the country could find sustained peace. I badly wanted to be one of those tourists and return one day. But even then, in 2011, it was hard to imagine the necessary peace coming. Contrast this with Eric Newby’s experience. A British officer fighting in Italy during World War II, he was captured, was held prisoner, escaped, and was hidden and given aid by friendly civilians. After the war, he returned, eventually buying a house in the same rugged area of Liguria where he had previously been on the run. He wrote about his wartime experiences in Love and War in the Apennines, but his book about his experience returning to live in Italy after the war, A Small Place in Italy, connected more strongly with me. I couldn’t help but think back to the unavoidable sense that peace would elude Afghanistan indefinitely. The book forced me to think about war termination and the deep, and sometimes unsatisfied, desire to believe that the places we go to war will end up better for it.

Connected Soldiers, by John Spencer

Full disclosure, the author is a colleague and a friend. I had the good fortune of witnessing this book come together. And yet when I sat down and read it in full, it connected with me. John was an infantry platoon leader during the 2003 invasion of Iraq and a company commander returning to Baghdad in 2008, and the advances in technology and available connectivity between those two deployments fundamentally changed the way that his soldiers bonded with one another. Returning from a difficult mission in 2008, when each soldier could reach out to friends and family back home with phone calls, emails, and Facebook messages, was very different from the shared processing of shared experiences that characterized John’s 2003 deployment. The book raises questions about how some of the most important features of combat experience and veteran identity are changing.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Courtney White

Once a Warrior King and Memoirs of a Bangkok Warrior. Both captured the spirit of my youth as a young soldier.

I haven't read Tim O'Brien's "The Things They Carried," so can't comment on it, but the reviewer's reference to the "unreliable narrator" was interesting. In literary criticism, an unreliable narrator is one who would lead the reader astray if his or her perceptions were accepted at face value. That's why such a narrator is considered to be "unreliable." Human fallibility in recollection even in bearing witness to a minor traffic accident is legendary; ask any police officer! But as a piece of (literary) work, the unreliable narrator is in a class of his or her own. As Abrams (Professor M.H. not General C. W.) points out: "The fallible or unreliable narrator is one whose perception, interpretation, and evaluation of the matters he [sic] narrates do not coincide with the implicit opinions and norms manifested by the author and which the author expects the alert reader to share with him," (A Glossary of Literary Terms, 5th edition). There is, therefore, a distinct difference between an unreliable narrator and an unreliable author, particularly with regard to the connotations the author positions readers to accept as valid. This is true, even with regard to an authentically related authorial experience of war, and the difference becomes particularly critical when the war in question has been systematically misrepresented by unreliable historians.

It took me a while, but I think I know why O’Brien wrote such a disgraceful book titled The Things We Carried, he wanted to shock high school students and others by writing some of the most absurd nonsense ever rolled into one book.

Of course, many await a movie version that continues to put the Vietnam veteran in a bad light. It’s bad enough that supposed “documentaries” such as Burns’ and Novick’s The Vietnam War was thought to be real – it is a real something and historians who were never there applaud the book, but it is not a realistic portrayal of the Armed Forces in Vietnam. But good things don’t get published or put on the big screen.

91% of Vietnam Veterans say they are glad they served and have good reason to – not based on anything O’Brien (et al) has written.