I took my current position as Army deputy chief of staff for operations, plans, and strategy back in June 2019. If at that point you had told me that during my time we would be confronted with the most serious global pandemic in memory, I would not have believed you. Yet here we are, well over a year into the COVID-19 crisis. This crisis has cost hundreds of thousands of lives, shaken our society on numerous fronts, and challenged many of our most fundamental institutions. Despite these challenges, I am incredibly proud of the work the Army team has done during this critical period in our nation’s history. I don’t know that many are fully aware of the Army’s role in this crisis, but understanding it is crucial. It represents a powerful example indicating our readiness to respond to a wide range of other crises that could yet emerge, so let’s rewind the tape.

In late January 2020, the Army had just rapidly deployed thousands of soldiers to the Middle East to deter Iranian aggression while beginning to flow twenty thousand soldiers to Europe for Defender 20, the Army’s largest exercise since the Cold War. These undertakings also came amid the continued reinforcement of the Korean Peninsula. As COVID-19 cases were reported from the Indo-Pacific region, the Army took action by dynamically repositioning itself to protect our force and maintain our critical missions. We made strategic decisions to scale down the Defender exercise and began to plan for the new mission to defend the homeland against COVID-19. Today, the Army continues to maintain global security with a worldwide presence alongside our allies and partners, even as we have simultaneously engaged in the fight to defend our nation for the past fifteen months.

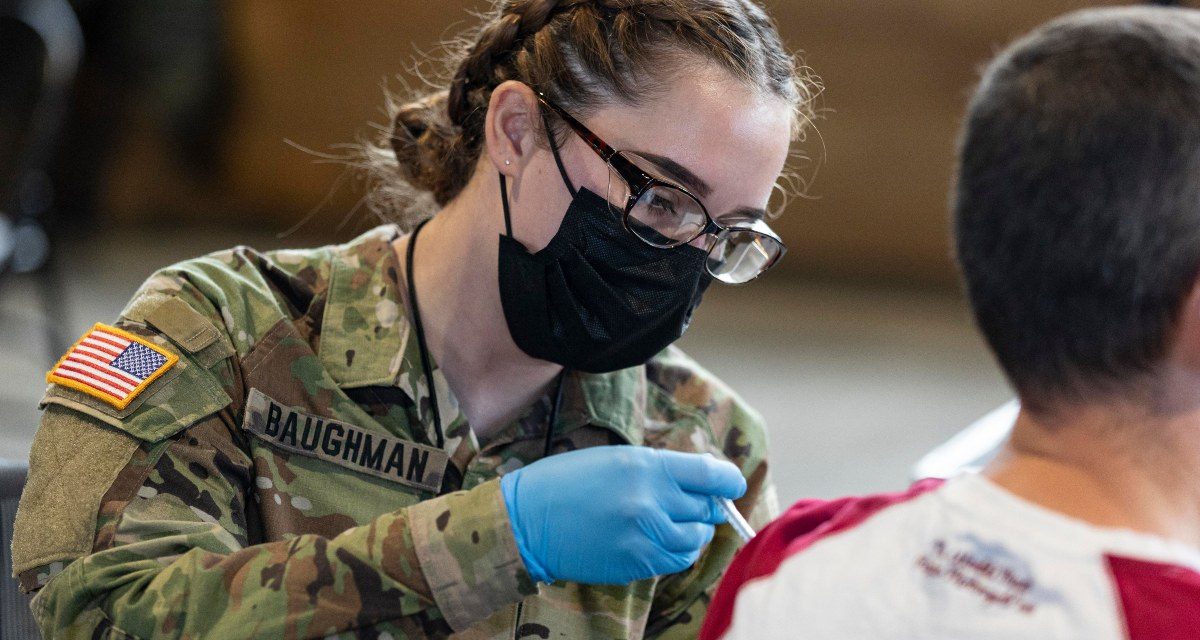

This fight against COVID-19 has been unique. When we deploy the Army, normally the American public is not on site. Over the past year, the Army has been on the front lines against COVID-19, with American men and women in uniform stepping up to protect their communities. Numerous large-scale sites across the country, for example, have treated, tested, and vaccinated millions of Americans. When Americans encounter these, what they see is the very best of the Army: mothers, brothers, doctors, teachers, truck drivers, and engineers—all soldiers working to defend our loved ones from the worst effects of this pandemic.

The spirit exhibited by Army soldiers—active, guard, and reserve—is not new. The Army has cultivated a culture based on lessons learned over centuries. In the Revolutionary War, quick response Minutemen organized into strategic skirmishers and built the Army that defeated an empire. After early challenges and battlefield setbacks during World War II, a shocked Army rebounded, devising a surprise operation launching tens of thousands of airborne and amphibious soldiers, paving the way to liberate Europe. Simultaneously the Army sent hundreds of thousands of soldiers across the Indo-Pacific to pacify Imperial Japan. And you see that spirit continuing today. As we continue through a crisis that few could have imagined just over a year ago, the Army continues to pull forward every tool it has to meet the challenge.

Global Agility

When I started off as a young officer in the 82nd Airborne Division, one of my early combat experiences was as a battalion logistics officer in the Division Ready Brigade during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. As the DRB, our job was to be the first unit out the door in a time of crisis. When Saddam Hussein crossed into Kuwait in August 1990, we were in the Persian Gulf region in days. America needed to deter further aggression, and the US Army provided that immediate, on-the-ground response. As it became clear that Hussein would not leave Kuwait willingly, General Norman Schwarzkopf, then commander of US Central Command, devised the battle plan. Gen. Schwarzkopf thought deeply about how to win this type of war, holding numerous war games even before Hussein’s invasion. He took the threat seriously, building up combat power in the region while keeping a watchful eye on Hussein’s forces. After the air war commenced in early 1991, forces from the Army, Marines, and dozens of coalition partners readied for a brutal ground war. Gen. Schwarzkopf executed a plan incorporating the whole of the coalition. Units from the Army, Marines, and members of the Arab League crossed straight into Kuwait to liberate the capital and secure the oil fields. Other members of the coalition, including my unit with the 82nd, took a left hook into Iraq to cut off any reinforcements. Our coalition won the ground war in four days.

The lessons of the Army’s role in Desert Shield and Desert Storm continue to resonate today. Some parts of the Army move rapidly, preparing within hours and moving within days. Those parts enable immediate response across the globe, deterring adversaries and reassuring friends. Other parts plan, synchronize, and eventually move mountains to provide campaign quality landpower.

Strategic Competition

In my current assignment, I serve in the Pentagon by focusing on how to employ the Army of today and how to design the Army of tomorrow. While this is not a battlefield assignment, the lessons from America’s previous fights continue to echo. The problems we face are new, but we continue to react, learn, and adapt with each new challenge. One such challenge is our accelerating strategic competition with Russia and China. Since the invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, repeated Russian encroachment in Eastern Europe has posed an immediate and persistent challenge to the US-led global order. To provide rapid reassurance to our partners and NATO allies in Europe, the Army, through the European Deterrence Initiative, began to rotate armored brigades into Poland and the Baltic states. In the medium term, we began to improve our European bases and pre-positioned stocks of critical equipment, proving our commitment to our European allies.

Similarly in the Indo-Pacific, China has repeatedly flouted international agreements, going on to claim, build, and arm multiple islands in the South China Sea while suppressing protests in Hong Kong and menacing Taiwan. To respond immediately, the Army has rapidly developed and deployed air defense capabilities and military advisors and expanded our exercises with allies and partners throughout the region.

In the long term, though, the Army recognized the need to change its plan, specifically our concepts of how we fight and who we might fight in the future. We simulated numerous conflicts, learning what sets of capabilities we would need to reliably win. This analysis gave rise to the concept of Multi-Domain Operations, which now forms the North Star of our strategic direction. As MDO evolves from concept to credible deterrent, the Army continues to adapt our resources to meet these emergent challenges. We have established V Corps to focus a large field headquarters on Europe, and we’ve begun to employ multi-domain task forces in the Indo-Pacific and will soon do so in Europe for expanded capabilities. We are calibrating the Army’s posture around the world to ensure ready and modern forces are responsive to global demands in competition and crisis. Recognizing that adversaries may view the global pandemic as an opportunity, the Army continues to pursue its readiness and modernization priorities to ensure its capabilities now and into the future.

The Fight against COVID-19

The Army’s persistent, self-critical eye has been crucial to its response to COVID-19.

Once we made contact with the virus, we planned—rapidly in the beginning and then more deliberately as time progressed. In the rapid phase, we looked at where we needed to accept risk and where we could reduce it. We stopped or rerouted tens of thousands of soldiers and pieces of equipment in movement between four continents, ensuring our deterrent posture and readiness to support domestic response while minimizing the risk to our people. We transitioned exercises like Defender, safeguarding the integrity of units critical to domestic support like hospital personnel and engineers. As it appeared more likely that states’ and localities’ medical personnel and equipment would be overwhelmed, the Army adapted, pulling from its deep bench of active and reserve personnel to support the whole-of-nation response.

Then we surged, providing capabilities wherever needed, and improvising along the way. Governors activated National Guard soldiers at the highest levels in history for missions ranging from facilitating drive-through testing in West Virginia to supporting food banks in California.

After sending hospitals to Seattle and New York City to support local authorities in the first wave of COVID-19 cases, the Army Reserve redesigned critical medical capabilities within days, forming urban augmentation medical task forces. In just over a month last spring, Army North coordinated sending seventeen of these task forces to eight states, including ten to the New York tristate region, relieving pressure on local hospitals. The Army Corps of Engineers transitioned vacant hotels into surge-capable clinics and continues supporting civilian response across the nation. We have pulled numerous logistical and medical capabilities from the active Army to rush vaccination capacity to the points of greatest need. At the same time, Training and Doctrine Command completely retooled and refit the Army’s recruiting and training pipelines to deliver trained, disciplined, and fit soldiers. As rates advance or decline across the nation, the Army will continue to reassess our posture so we can be ready for the next crisis.

The Army’s Legacy

The Army that our fellow citizens have seen over the past year during the COVID-19 response is the same organization that has fought and won from the deserts of the Persian Gulf to the shores of Normandy.

The Army has faced crises before and we will face them again. Whether it be world war or a global pandemic, whether domestically or across the globe, the Army and our people know their duty and are prepared to meet the challenge.

Lt. Gen. Charles Flynn is the US Army deputy chief of staff for operations, strategy, and planning. He has been confirmed as the next commanding general of US Army Pacific.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Featured image credit: Spc. Robert P Wormley, US Army

In all fairness to Readiness, General, I think that the US Army can help the world better by "chopping some tanks and M88s" to the US Marine Corps who have divested all their M1A1 Abrams to the US Army and expects the US Army to provide the heavy tank firepower in the future.

This is absurd. Essentially, the USMC believes that it cannot afford the M1A1s and wants to save the money to buy new systems, citing that the M1A1s are too heavy, which they are.

The best approach would be for the US Army to pay for a contingent of Mobile Protected Firepower Light Tanks and M1A2SEPs, give them to the US Army, and perhaps assign Army tankers or Army gunners or TCs to those tanks and have a Joint-crew of Marines in each tank, or let the Marines "borrow" the tanks and maintain them in exchange for who knows what. There is just no way that the Marines are going to field tanks again, and if the US Army is going to win in a peer nation fight, it will definitely need tanks, heavy or light, again.

As the future US Army Commanding General of the Pacific, it seems logical to forward-position tanks on Amphibious ships in INDO-PACOM as a deterrent than flying them in via USAF cargo plane when called for and when the Marines are under attack. Now it can be the GDLS "Griffin" or BAE M8 AGS with Active Protection and ERA, or the M1A2SEPv3 TUSK II with Trophy APS. Either way, I think the bottom line is that the US Marines just can't afford tanks and said that they're too heavy.

The M1A2SEPv2 has a weight of 71 tons without Trophy, and the US Navy's SSC hovercraft can carry 74 tons. But the best bet would be the Light Tank that the US Marines don't want or can't afford.

I would highly recommend that the US Army fund some tanks to the USMC ASAP or risk getting blamed for not providing proper tank support in the future. As preposterous as this notion sounds, that's akin to USMC having inferior 105mm M60A1s with ERA and the US Army having the newer, better, more capable 120mm M1A1s in the 1991 "Desert Storm" Gulf War.