A few years ago, I showed a senior officer a draft strategy. He looked at it, and then looked at me with a Christmas orphan’s unsatisfied disappointment: “We need to more clearly explain our ends, ways, means analysis,” he said, leaving silent the implied threat—or it’s not a real strategy. Underwhelmed but outranked, I grudgingly included the formula.

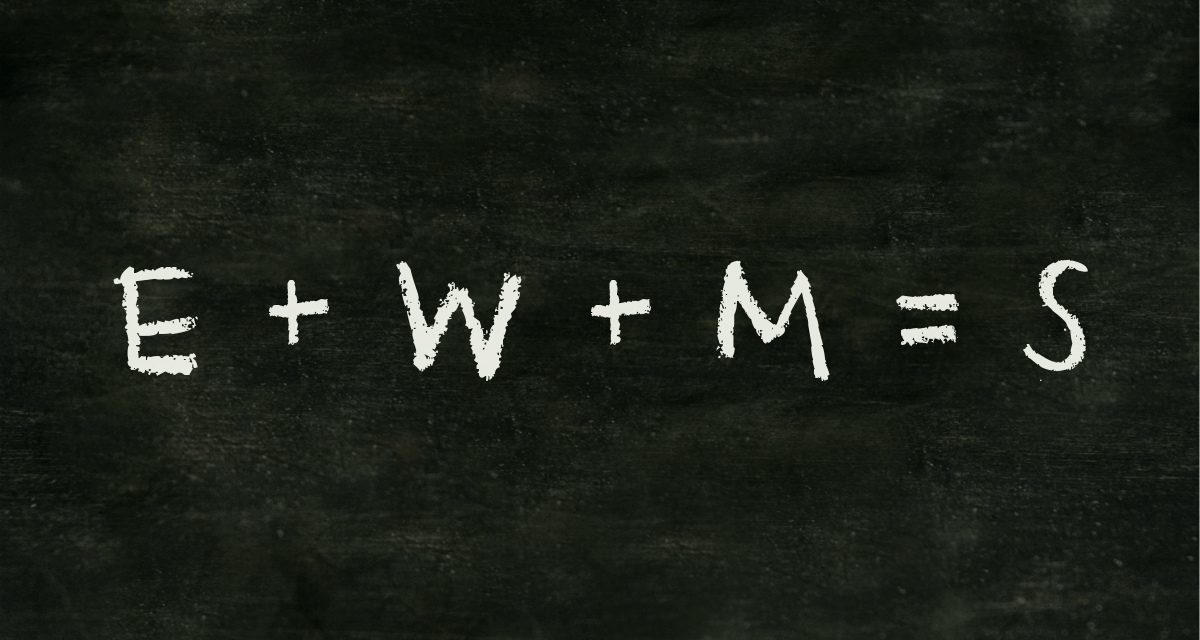

American strategists know the formula well. It’s Col. Arthur Lykke’s, published in Military Review in 1989, and since then widely taught and promulgated by the US Army War College: “Strategy equals ends (objectives toward which one strives) plus ways (courses of action) plus means (instruments by which some end can be achieved).” It is convenient and concise, short enough to fit cleanly onto a PowerPoint slide and clear enough to be expressed as an actual mathematical equation: ends + ways + means = strategy (less residual risk). This simplicity has driven universal adoption; nearly every single strategic document the American military generates is directly or indirectly influenced by Lykke’s formula.

But what if this dominant view is bad for American strategy, as Jeffrey Meiser points out in a recent essay? While he acknowledges “some value” to this method, Meiser also alleges the formula “has become a crutch undermining creative and effective strategic thinking” because it channels practitioners toward “viewing strategy as a problem of ends-means congruence” (e.g., do we have enough troops to do the job?). Is Meiser right? Is Lykke’s model a tyrannical mental straightjacket, constraining American strategists?

I think so. Lykke’s model is flawed on four counts: (1) it’s too formulaic, (2) “ends” don’t really end, (3) it minimizes the adversary, and (4) our strategic performance since widespread adoption has been unremarkable at best.

Strategy cannot be fixed into place with equations. War’s units of measure are as different as bombs and bandages; set numbers of rifles do not directly convert to a sense of security (in fact, sometimes, the net sense of security decreases with more weapons!). Equations might work for straightforward planning (e.g., if the objective is to get a tank to Timbuktu, then this will require five hundred gallons of fuel), but strategy is not so clear-cut. Just as National Security Advisor Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster has criticized PowerPoint as “dangerous” because “some problems in the world are not bullet-izable,” most strategic problems in the world are not equation-able. At best, strategy is “nebulous.”

And let’s face it, neither do “ends” really end, which is the reason a strategy publication like The Infinity Journal features a tagline that reads: “Because Strategy Never Stops.” Even at the conclusion of decisive conflicts like World War II, the need for strategy in Germany and Japan did not end with Hitler’s death and Hiroshima’s destruction. America met massively important objectives—but we’re still there today! Or, consider the laundry list of commanders and strategists that have stated, unequivocally, that “this” is the “decisive” year in Afghanistan—where we’ve been nearing the “end” every year for going on two decades. Which begs a question: is there really a near-term, hard-stop “end” in the Forever War, the Long War, or the “era of persistent conflict?” While we should always aim for some desired objective, some better state, we should do so with modest expectations that explicitly acknowledge the practice of strategy is never final and always uncertain.

This uncertainty exists because the enemy gets a say in strategy-making, a factor that’s excluded from Lykke’s formula. This isn’t some minor detail; this is a very Big Deal. Lykke’s model is entirely preoccupied with one’s own ends, one’s own ways, one’s own means—a mental half measure that inevitably leads to the myopia strategist Edward Luttwak has described as strategic “autism.” It’s almost banal to point out, but, any definition or way of articulating strategy must have at its core a deep consideration of the adversary (and interactions with that adversary). Anything less is professional narcissism.

This may be why Lykke’s equation has run alongside a not-too-distinguished period of America’s strategic history. As historian Richard Kohn observed in 2009, this post–Cold War era has shown the “withering of strategy as a central focus for the armed forces, and this has been manifest in a continual string of military problems” including the Gulf War’s incomplete result, Somalia’s bloodied withdrawal, and “initially successful campaigns” in Iraq and Afghanistan “which metastasized into interminable . . . guerilla wars of attrition that have tried American patience and will.” Correlation is not causation, but, it is curious that this relatively unsuccessful era has gone in parallel with American strategy largely developed by an enemy-omitted, end-seeking equation.

My own explanation for Lykke’s stranglehold on strategy is the American military (like all militaries) prefers to plan for certainty as opposed to strategizing for uncertainty. Gen. Omar Bradley once (potentially apocryphally) said, “Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics.” In line with this sentiment, for the American military, strategy is too often a necessary evil, flyover territory—just get that ends-ways-means stuff done quickly so we can get on with the really important stuff (like supply).

That said, we shouldn’t throw out any useful tool, even if it is limited; we should, instead, ensure the tool is used properly. Lykke’s model is clearly a better fit for planning than strategy-making, as a check on means-end feasibility. So, if not Lykke, where should strategists look to for a core logic to govern strategy development?

Here we return to Meiser, who points to Barry Posen on grand strategy (“a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself”) and Eliot Cohen on strategy (“a theory of victory”). The key word is “theory.” Others, including Tami Biddle and Colin Gray agree. As Gray has written, “strategies are theories, which is to say they are purported explanations of how desired effects can be achieved by selected causes of threat and action applied in a particular sequence.” Theory forces the strategist to describe how and why success is to happen against a competitive foe.

Thinking of strategy as theory has the distinct advantage of placing primary focus on engagement with the enemy, while lessening the importance of getting to some “end.” This is better.

But, just as strategy never ends, Lykke’s formula likely won’t either. We’ll have to aim for sustained disregard, so that the next time a senior officer asks for a strategy, he or she won’t expect a formula; maybe instead, we’ll use theory and our words.

I agree in large part with the premise of this article. Strategy is a continuous process and we strive to achieve and maintain a position of relative advantage through the effective use of the means at our disposal orchestrated in the optimal time and space against the system in some fashion. Lykke was not the first or only theorist to put forth an ends, ways, means way of looking at strategy. B.H. Liddell Hart also defined strategy as "the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy."

Our 'desired future conditions', erroneously (in my honest opinion) referred to as 'end states', are what the policy makers (or anyone in a position similar) believe to be favorable circumstances within the system for us (in this case the United States). However, these perceptions are constantly changing with each new input and even with changing of policy makers opinions, education or election. It is not just the 'enemy' or adversary we are acting against either. Understanding the context and all actors as well as the environment is critical to crafting the best strategy possible.

This is a very relevant article and sparks debate and thought, which is critical to our education and preservation of open mindedness necessary to ensure we do not become static and accepting of institutionalized ideas such as the ends-ways-means construct as the end all, be all solution. It is valuable as a tool, much like doctrine. However, it is a starting point and as with doctrine, a place to anchor ourselves for further debate and discussion such as this. I would not think any of the authors mentioned here or elsewhere presumed to have 'the' solution. As stated, these are theories and we must be educated and experienced enough in their evaluation and use to modify, adapt or discard them when and where appropriate based on contextual understanding.

Strategy can be simple as indicated in this article, depending on context. It can be enormously complex as well, when dealing with a complex and adaptive system with many actors (friends, foes, and neutrals) residing in a complicated globally enabled environment. How do we orchestrate all of the means available to us across the tools of national power (read whole of government) in time and space in an adaptive, responsive manner to gain and attain a position of relative advantage within a continuum? Constant feedback from innumerable sources that must be synthesized and incorporated into a comprehensive analysis to make a best guess as to the best use of available means, somewhere, at some time, to influence the actors within the system in a manner that helps us maintain a relative advantage overall. Everything we do must be looked at as 'long term' and generational in my humble opinion. Everything we do ultimately leads to second, third and fourth and fifth order effects and so on.

Ends-ways-means (mitigated by risk) may not be perfect, but it is a good starting point. Thanks for the thought provoking article.

This ignores that the point of a strategy is to try and provide an ordered structure for implemetation — Webster defines strategy as, "a careful plan or method [ways] for achieving a particular goal [ends] usually over a long period of time" (brackets are mine). The flaw in Lykke's "equation", or at least its application, is the assumption that ends, way, and means are constants. Ends are a function of actions by the enemy, by allies, by neutrals, and by internal factors — E = f(e,a,n,i). Ways are a function of means — W = f(M). Characterizing strategy as nebulous or theoretical renders it less than useful for real life…think of all those strategists out of jobs!

I have long thought we think within too many contraints when it comes to strategy as well as we force our selves to have an endstste. This is because we want to be able to measure success and with our an endstate we won't be able to get those metrics. I personally think we need to get away from our trains of thought that have dominated the post 9/11 era. Instead it might be more fruitful to think of our strategy as Ash Carter did in 2000 with his ideas of preventative defense. Under that premise the "long war" isn't an on going conflict but a preventive defense measure in place to increase difficulties and deter enemies FOM in order to conduct attacks. When looked at it in with that lens interdiction across the globe, when done within an underlying strategy or status quo we want to maintain, can be the effective means and ways to maintaining our national defense.

I think the fundamental principles of ends, means, and ways are solid, but American application has tended to be amateurish and lazy. Our default "strategy" has been heavily means-focused: building a large and proficient military, and expecting firepower to fill in the blanks. When we were willing to use absolute levels of force (World War II), this simplistic strategy was sufficient: we didn't need to understand our enemies if they were dead.

In more nuanced situations, strategists need (honest) ends to work towards, and they need to understand the enemies, allies, and neutral nations who will be participants in those ends. If the political leadership proclaims a goal of freedom, liberation, rainbows, and unicorns, the military strategists will be failing if they just salute and try to do the impossible. Likewise, if the war is against people whose language we don't speak, in a culture we don't understand, strategists aren't even equipped to say if the desired end state is practical.

Great piece. I've stumbled upon this while searching if anyone had mentioned before that the W+E+M equation is so problematic. We see it not only in the military sphere but also in other business fields. Strategy start when the we are trying to impact is not a closed system. If it is, as mentioned in the "fly my tank" example there's no need for strategy. And because we are handling open systems, which are open in time ("there's no end") and in space (the counter body is acting and reacting by himself), we cannot apply the different parts of the so called equation altogether. However, I do think that portraying EMW not as an equation but rather as a force map, in which one should also inspect HOME (who we are) and the OPPONENT we can move forward a very viable strategic discussion.