After a stunning military advance, the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan in August 2021. This seemingly sudden takeover, with hundreds of districts falling like dominos, took most observers by surprise. After all, maps had long shown most of Afghanistan’s districts under government control, with the Taliban holding just a small share.

But what appeared to be an almost overnight shift in control was in fact the result of an insufficient understanding of how armed groups in conflict zones around the world operate and exercise control. How the security community commonly conceptualizes and maps territorial control does not accurately capture reality on the ground. This makes it exceedingly difficult to understand how and why the balance of power between governments and armed groups shifts—sometimes rapidly—over the course of military campaigns.

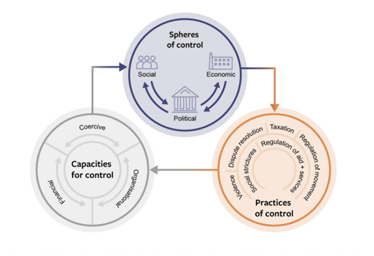

Drawing on a recently published study, we argue that there is an urgent need to rethink how armed groups exercise control. The security community, donors, and international organizations can benefit from looking at what we call the entire “cycle of control,” which considers the practices armed groups apply to exercise control in different spheres, and the capacities they draw on to achieve this. Adopting a fuller understanding of control can help policymakers move beyond simplistic maps and develop real-time analysis of control during irregular warfare.

What We Get Wrong about “Control”

The Taliban were in de facto control of much of the population in Afghanistan long before August 2021. The government might “control” a district capital, even if much of the rest of the district was actually in Taliban hands and government district officials resided elsewhere for security reasons. In these rural areas, the Taliban had set up a parallel administration complete with tax collectors and courts. They allowed the government to function and government officials to deliver services so long as their doing so benefitted the Taliban. From this vantage point, it’s not hard to see why so many districts fell to the Taliban not through military offensives but through mediated handovers and tacit deals.

Another part of the problem is that the dividing lines laid out on maps were rarely so clear-cut on the ground. In fact, most analyses of wartime control rely on territorial markers (e.g., demarcated front lines) or the reported presence of armed actors in a defined locale (e.g., checkpoints or the occupation of military installations). But the battle for control cannot be thought of in zero-sum terms. In Afghanistan, as in most contemporary civil wars, control was fluid and overlapping, even in some major cities. Taliban courts, for instance, operated a short drive from the embassy district of Kabul. Color-coded maps, which inherently favored the government side that was more visible in urban centers, tended to badly underestimate Taliban power and capacity.

A larger issue is that armed groups like the Taliban tend to seek control over people and behavior—not necessarily territory alone. Armed groups do not have to hold territory, or even have a stationary presence, to control or govern it. Where lines of control exist in theory, armed groups often traverse them, seeking to infiltrate and influence civilian behavior through intimidation, resource extraction, or other means. While this is particularly true of irregular, asymmetric, or low-intensity conflicts, it is also borne out in some more conventional or interstate wars.

So how should we be mapping control differently? An important starting point is to think of fluid and overlapping layers of influence exerted by various actors—armed groups, the government, and others. By separating out the different means through which armed groups vie for control, it becomes easier to measure and track significant shifts. Our work points to three distinct but interrelated dimensions that form a “cycle of control” (Figure 1). These three dimensions—spheres, practices, and capacities—shed light on armed group control and provide valuable indicators for tracking their influence.

Spheres of Control

The first dimension of control is the various spheres—economic, social, and political—in which armed groups exercise control over civilian life. Nearly all armed groups try to control economic activity. They do so not only to fund their causes, but to reinforce their own legitimacy. Some armed groups leverage economic influence via state-like behavior and the creation of bureaucratic institutions, which in turn reinforce their legitimacy. Crucially, by shaping the economic sphere, armed groups can exercise not only direct control over civilians, but also indirect control, through changes in wider economic practices and standards. Even if we look at the largely conventional war in Ukraine, an analysis of the economic sphere is telling. For instance, Russia planned to introduce a ruble-only currency system in some of its occupied territories (such as in Kherson in May 2022, before later revoking such plans following Ukraine’s counteroffensive), indicating early on how important specific areas were for Russia. However, economic influence can, and often does, considerably exceed territorial presence.

Second, armed groups attempt to control the behavior of civilians. The substance of the rules they enforce is typically molded by the group’s ideology, but these rules are about eliciting compliance. For example, actions such as dressing a certain way, speaking a certain language, or having a specific ringtone or haircut all demonstrate a certain kind of obedience and confirm armed group dominance. This exteriority not only sends a message to the armed group, but also signals the degree of armed group control to the wider civilian population in an immediately visible way.

Lastly, in attempting to remake the political landscape in their image, armed groups seek to co-opt, capture, or replace decision-making and authority structures. This includes co-opting state structures, coercing informal authorities into doing armed groups’ bidding, or attacking and destroying existing power structures. They also often exploit the political weaknesses of their enemies. If their enemies are corrupt, they pose as incorruptible. Another common tactic is to exploit civilian anger at violence and civilian casualties—a surprisingly successful political maneuver, even where the armed group themselves kill far more civilians.

Practices of Control

Within these broad and overlapping spheres of control, armed groups adopt a number of practices and tactics to further their objectives. It is these behaviors that are most important to understand and monitor.

The most obvious practice is violence. Violence can, however, be misleading. Many current mapping practices rely on violent incident data. Yet the sheer volume of incidents tells us little about the nature of dynamics on the ground. The most important things to understand regarding violence are how a specific armed group uses violence (or refrains from using violence) to exert control, and what any shifts in tactics signal about control. For example, groups will look to target the “old system” to impose social control. In central Mali, in its early days, the group Katiba Macina, a member of the jihadist coalition Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), used violence to remove or undermine existing symbols of authority to establish its control. Violence may drop or become more selective where the armed group is more confident of its influence and control. In parts of Somalia where al-Shabaab feels it can strike a deal with the population, the threat of collective violence acts as an incentive for civilian compliance, suggesting that a drop in violence in some areas may indicate consolidation of al-Shabaab control.

Beyond violence, an armed group may have an extensive repertoire of practices used to elicit civilian obedience. A common one is dispute resolution. Providing their own forms of dispute resolution allows armed groups to capitalize on civilian dissatisfaction with insecurity and injustice. Dispute resolution, in turn, allows armed groups to establish a presence in communities and links with civilians. For al-Shabaab, courts allow it to present a more positive image to civilians, counterbalancing the violence it inflicts.

How armed groups provide justice and dispute resolution can provide both crucial insights into control and a foundation for early warning. Tracking fault lines within a society may be key in identifying early forms of mobilization that occur before violence. While grievances exist in all societies, it is important to monitor how these are utilized by armed groups to exert control. In Afghanistan, people often started using Taliban courts before the Taliban had established territorial control, and continued to do so even after the government had pushed the group back territorially. It was a cheap, easy, and adaptable way of responding to a clear civilian need. In Mali, JNIM members have used mobile courts to help project a presence beyond the areas in which they are physically present.

As they evolve, many armed groups also extract taxes. More formal and predictable than ad hoc extortion, armed group taxes reinforce their desired image as a state-like entity and nod to the idea of a social contract (even where the armed group doesn’t provide much in return). Al-Shabaab has a strikingly sophisticated strategy of economic influence, ranging from taxation to collusion in various aspects of international commodities trades. Al-Shabaab can coerce businessmen in the ostensibly government-controlled capital Mogadishu into paying taxes and reportedly earns more revenue than the government collects. Taxation is a crucial source of revenue, but it also allows armed groups to exercise control well beyond the economic sphere. These practices also shape behavior—for instance, when taxing goods or behavior that are considered to be morally wrong, such as alcohol, cigarettes, or khat.

Another important set of practices concerns the degree to which an armed group allows civilians to access aid and services. For example, in Mali, JNIM instructed member groups to facilitate the access of humanitarian actors, rather than attacking them. Regulating access to areas under JNIM control for humanitarian and NGO workers boosted the popularity of JNIM and also reinforced the image of the group as the de facto authority.

Capacities for Control

So how do armed groups get people to go along with all of this? We argue that armed groups have three main types of capacities: coercive, organizational, and financial. Gauging these capacities allows us to estimate their strength more clearly.

Coercive capacity is the bedrock of armed group control. Orchestrating violence that furthers the group’s strategic objectives requires command and control, the ability to recruit, selectivity in employing violence, intelligence-gathering capacity, and other resources and skills. Organizational capacities enable an armed group to translate central-level decisions, policies, and strategies into consistent practices of influence and control. In some instances, there may be markers of organizational development, such as the establishment of a code of conduct. The consistency of rules across geographies and a clear chain of command are important markers.

Finally, an armed group’s funding and access to financial resources determine its ability to cultivate cohesion and pay for vital things like salaries, arms and ammunition, training, travel, oversight, and a range of other organizational functions. A broad understanding of an armed group’s funding base (e.g., local contributions, extortion, third-party state sponsorship, a diaspora, or taxation) is an important starting point. What appears to be most important is the ability to elicit predictable and dependable financial flows. Although this may happen later in an armed group’s evolution (or never at all), the existence of an internal mechanism that allows the group to coordinate revenues and distribute them according to strategic priorities is a marker of high capacity.

Viewing Control through a New Lens

In recent years, many individual donors and international organizations have explored ways to improve development, investment, and other forms of engagement in conflict zones. This has included calls for increased funding in areas such as climate finance, to help the most vulnerable adapt to the impacts of climate change. The reality is that states are not the only actors in these contexts, and in some cases, not even the dominant ones. Understanding how armed groups exercise control is therefore crucial. Our framework provides a means through which external actors can examine the forms of control exercised by armed groups and the implications for engagement and interventions in conflict zones.

Understanding how armed groups exercise control in different spheres and the capacities they draw on is crucial for operating in conflict zones, where various authorities often compete over control and influence and government institutions remain weak. Despite important contextual differences, there are striking similarities in how armed groups operate in places like Afghanistan, Mali, and Somalia. Crucially, armed groups use justice, taxation, and different types of violence to exercise control over populations. Changes within these three areas demonstrated changes in a respective armed group’s position of control.

The dominant understanding of control, viewed through the lens of territory, insufficiently captures how armed groups operate. Control does not have clear dividing lines or even require armed groups to be physically present. The cycle of control can thus help improve real-time analysis of armed group control that goes beyond simplistic color-coded maps.

Ibraheem Bahiss is an Afghanistan analyst with the International Crisis Group. He has previously written for ODI, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, and the Norwegian Centre for Conflict Resolution, among others.

Ashley Jackson is codirector of the Centre on Armed Groups. She has over a decade of experience working in and on Afghanistan and researching armed groups.

Leigh Mayhew is a research officer at ODI, a fellow at the Centre on Armed Groups, and a Civil War Paths fellow at the Centre for the Comparative Study of Civil War.

Florian Weigand is codirector of the Centre on Armed Groups and a research associate at the London School of Economics. He is the coeditor of the Routledge Handbook of Smuggling (Routledge, 2021) and the author of Waiting for Dignity: Legitimacy and Authority in Afghanistan (Columbia University Press, 2022).

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: AMISOM Public information

A government is nothing more than an armed group, with legitimacy, in the paradigm cited by the authors. The whole question is who is legitimate: is it the government we choose to recognize, or the group that performs the function more effectively and reliably (from the perspective of the locals) but without our stamp of approval.

The government we kept insisting was legitimate, our puppet regime, lacked legitimacy with the people that mattered.

Regarding control of the countryside, Bernard Fall figured this out in the 1950's in Vietnam. People should get more familiar with his work. i.e.. Street Without Joy. If our government leaders had listened to him, we would now live in a different and I dare a better world. As an advisor during the Vietnam War, I saw firsthand what Fall was writing about. Failure to understand the implications of his work led to major mistakes in Afghanistan

Great article Ibraheem! I would like to know your opinion of how maps COULD be beneficial in the context of armed groups. Would maps that plot where evidence of armed NGO extortion, violence, and ‘judicial courts’ help to visualize the geographical extent of their control/influence? And, what instruments of power do you feel mitigate, or effectively counter, each of the three capacities (ex. Local gov law enforcement where extortion is evident, etc)?