Nearly every neighborhood in Medellín, Colombia, has a combo, or local street gang—almost four hundred in all. They earn most of their money from local drug sales. Some also run protection rackets, while others market legal goods—arepas, eggs, and even cooking gas—to locals. All these revenues make each Medellín neighborhood a valuable prize for combos to control.

That competition for prime territory should be a recipe for violence. Yet the city has an annual homicide rate far lower than that of cities like Chicago. Why?

The short answer is that Medellín’s gangs have learned how to cooperate rather than fight. Unfortunately, Medellín’s relative peace comes at a hidden price: less violence in return for stronger, better organized, and more popular gangs.

Collectively, we have spent the past decade studying organized criminal groups in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Chicago. We see governments faced with the same terrible trade-off throughout cities in the Americas: more violence or stronger and better organized criminal groups. Different cities have made different choices—often without even knowing it.

The Pact of the Machine Gun

Take Medellín. The city’s hundreds of combos are the lowest rung of an elaborate criminal hierarchy. The street gangs eke out a living dealing drugs and shaking down buses and little shops. But the real money in the city doesn’t come from selling cocaine and marijuana to slum dwellers. A set of more sophisticated groups have learned how to shake down the big construction firms and launder money for global drug rings. They are also the wholesale middlemen for the combos’ retail drug operations. There are about seventeen of these powerful Mafia-like organizations, commonly called razones (although the government prefers bandas criminales or “criminal bands”).

Years ago, the razones decided they had to find a way to keep themselves and the street combos from fighting. The consequences of failure were clear. From 2009 through 2012, two powerful razón leaders struggled for dominance. Every other criminal group in the city lined up behind one or the other and, for a brief time, Medellín became one of the most violent places on the planet.

Aside from the obvious costs to the public, there were also costs to the gangs themselves. The crime bosses lost the low profile that had shielded them from state repression. Suddenly they saw their photos in the newspaper and the names of their organizations in print as police and journalists began to trace the money. Many razón leaders ended up in prison, where they still reside today.

To help keep the peace, and to build their own military and economic power, the razones invested heavily in organizing the street gangs. Their arrangements look less like wholesale-retail business relationships and more like political confederations. Street gangs in the same part of the city generally report up to the local razón. Mostly they maintain their autonomy, but the alliance means the razón can call them to war if needed. Each razón, meanwhile, also keeps the local peace among its subordinates, helping them manage disputes and coordinate to sell drugs at noncompetitive prices.

Razones also manage disputes among themselves—to avoid another city-wide bloodbath. To do that, in 2012 they built an informal bargaining table and governing board. Authorities typically call this criminal council La Oficina—”the office.” For a decade it has managed to keep the peace. The razones call it El Pacto del Fusil—”the pact of the machine gun.”

Ironically, by arresting the senior-most combo and razón figures, and holding them in the same prison blocks, Colombia’s government has helped to cement the pact. Faction leaders can interact face to face in prison, helping them build relationships of cautious trust. They can exchange information, reducing uncertainty. And the fact that they are all locked up together gives razones a powerful tool to control the streets. Most criminals in the city are expected to pass through prison for a time. Ignore the razón edicts, and they will make life difficult for you and your incarcerated friends.

Altogether, this system has had the unfortunate effect of making the razones stronger—but for peace this is a price some administrations have been willing to pay.

Occasionally the coordination between state and criminal leaders goes further. In 2019, when a war began to brew between two factions of razones, and Medellín’s homicides began to spike, imprisoned leaders (scattered across different institutions in the country) found themselves all transferred to new prisons in the same week. They were all put in the same holding cell for a few days, where there also happened to be a trusted criminal intermediary. Within a month, the homicide rate was back down to its previous moderate level.

Weaker Gangs, More Bloodshed?

Systems of criminal governance (like this one) are far from rare. In Brazil, street gangs have largely been subsumed by powerful, now national-level prison gangs, especially the Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Capital Command) and the Comando Vermelho (Red Command). In El Salvador, many street gangs were incorporated into mara organizations with hierarchical structures at the national level and international ties to branches across the hemisphere: the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Barrio 18 (18th Street) gangs. In Chicago, before 2000, there were the famous “supergangs,” such as the Vice Lords or Gangster Disciples. An upper echelon of criminal governors is a common feature of cities around the world.

For governments, there are some benefits to this kind of criminal consolidation. When a city’s criminal underworld is governed by a relatively small number of highly organized groups, it becomes easier for governments to take steps to reduce homicides—by creating incentives for groups and their leaders to avoid or eschew lethal violence.

This sounds treacherous and difficult, but there are many such examples. US cities, for instance, are fond of what are called focused deterrence strategies, in which city authorities meet with criminal leaders and pledge swift, certain, and severe punishments for future homicides. Comparisons of cities that did and did not use this strategy suggest that it’s somewhat effective.

There are also instances of governments directly negotiating pacts and ceasefires among criminal groups, such as in El Salvador. Short of such explicit negotiation, governments can create incentives by credibly promising to condition enforcement according to how much violence a gang employs.

But this approach is not without its costs, presenting policymakers with what we call the terrible trade-off. Creating incentives for criminal groups to reduce violence often leads the criminal bosses to strengthen or consolidate their control of the city.

One reason is that any policy that helps establish peace could provide more opportunities for organized criminal groups to earn illegal rents, especially through the retail drug trade. This is partly because citizens are less likely to buy drugs in the middle of a gang war. But it’s also because the more that criminal groups can coordinate with one another to avoid war, the more they can form cartels (in the economic sense of the term) and collude to charge customers higher prices.

To the extent that there is a quid pro quo between criminal groups and the government, maintaining a low-homicide environment can also mean fewer public resources to combat organized crime. Indeed, if peace among criminal groups is keeping homicides low, why would governments crack down on gangs and risk triggering more bloodshed? Conversely, governments that launch crackdowns on gangs may find their cities engulfed in turf wars that undermine state legitimacy.

Another pattern common across Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico is that peace and strong gangs help produce gang rule over residents of the local neighborhoods. Local gangs bring day-to-day order and dispute resolution. That may be good for residents and the local economy. Indeed, orderly slums can help facilitate urban development. Yet if gangs are allowed to govern these spaces, it is tempting for states to continue to neglect them.

Finally, while mass incarceration and even the arrest of criminal leaders rarely eliminates criminal organizations, it often shifts the center of control to the prison system. As in Medellín, sophisticated gangs use promises of protection or punishment inside prison to influence and organize criminal activity on the street. Across the Americas, periods of crackdowns and rising incarceration have been followed by leaps in prison-gang power on the street.

Eyes Wide Open

Making peace with drug gangs might be the right policy decision, even if it is an unpalatable one. But the key problem is that many governments are unaware of this trade-off.

One reason for this is that most police and city governments have detailed information on one crucial outcome: crime and homicides. Officials often have fine-grained, geo-coded data on crimes, and cities often run annual security surveys, tracking victimization and security perceptions.

But governments, the media, and citizens are often unaware of other outcomes, such as gang strength, profitability, or popularity. For example, surveys rarely capture the extent of criminal governance or legitimacy, and thus fail to measure the relative advantages criminals have in regulating everyday life. Likewise, many cities do not develop intelligence networks that can dynamically measure gang strength and profitability.

Thus, mayors or police chiefs can track homicides and hold their staffs accountable for improving these measures. But they cannot know whether criminal groups are growing stronger or weaker. As a result, they have no way of holding personnel accountable for results, nor of testing the effects of policies on these outcomes. That reinforces an unconscious bias—a tendency to manage what is measured, no matter how dysfunctional the outcome.

Tackling organized crime will be a decades-long struggle. The solution must begin with developing better information and intelligence systems—qualitative and quantitative—that can give governments and their publics a better view of the trade-off.

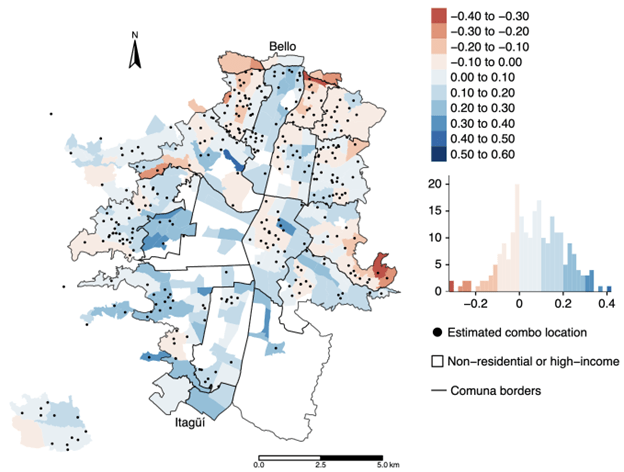

For six years we have done just this in Medellín—developing an independent, multidisciplinary team that has been able to develop intelligence and data that, up to now, the government has not.

Part of our strategy is using academic independence and reputations to develop enough credibility and trust to be able to interview criminal leaders and managers at every level. To date we have interviewed more than 110 middle- and high-ranking members of more than forty criminal organizations. We have also stitched together disparate data sources, and studied criminal and civilian responses to government interventions.

Finally, we have helped the city government develop better information systems on organized crime. For example, to measure gang strength, we asked residents how frequently either the gangs or the state responded to various common disputes, insecurity, and forms of disorder, such as handling conflicts with neighbors or responding to thefts. We used the answers to measure the level of gang rule in particular neighborhoods. Some areas, it became clear, are predominantly dominated by gangs.

We have also surveyed residents of Medellín about gang and state legitimacy, asking them how much they trust the local gang and the state, and whether they believe the gang and the state are fair. In some neighborhoods, our research suggests, the real authority seems to be the gang and not the state, and residents recognize this fact.

The Long Game

Ultimately, voters and policymakers may well decide that their priority is reducing violence. If so, they ought to understand that some of the means to get there—informal agreements, clustering leaders together in prison, or a quid pro quo that peaceful gangs will not face the same degree of law enforcement pressure—can come at the price of stronger gangs. And they should be aware that “pacification” strategies and other heavy and broad-based crackdowns on criminal groups could destabilize the existing groups and lead to a spike in killing.

Perhaps the best approach is for mayors and police chiefs to combine violence-reducing strategies like focused deterrence with efforts to reduce the illegal revenues gangs earn. These could be demand side (such as treating addicts, a major source of drug demand) or supply side (legalizing some drugs, such as marijuana). The idea is to undermine the core economic operations of the gangs while also incentivizing them to be more peaceful.

In addition, states need to be prepared for long and costly investments of security and services in their most peripheral neighborhoods. Many cities have gotten used to gangs doing the hard work of providing order in poor neighborhoods. If voters and their governments truly want to replace gang rule, they will need to get serious about offering social services, dispute resolution, effective policing, and well-functioning systems of justice in every neighborhood—not just the wealthy ones.

Christopher Blattman is professor of global conflict studies at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy and author of Why We Fight: The Roots of War and the Paths to Peace.

Benjamin Lessing is associate professor of political science at the University of Chicago and author of Making Peace In Drug Wars: Crackdowns and Cartels in Latin America.

Santiago Tobón is professor of economics at Universidad EAFIT in Medellín, Colombia.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: National Police of Colombia