Editor’s note: This article is part of the series “Compete and Win: Envisioning a Competitive Strategy for the Twenty-First Century.” The series endeavors to present expert commentary on diverse issues surrounding US competitive strategy and irregular warfare with peer and near-peer competitors in the physical, cyber, and information spaces. The series is part of the Competition in Cyberspace Project (C2P), a joint initiative by the Army Cyber Institute and the Modern War Institute. Read all articles in the series here.

Special thanks to series editors Capt. Maggie Smith, PhD, C2P director, and Dr. Barnett S. Koven.

China has enjoyed immense growth in the last two decades, while the United States has been distracted by two wars in the Middle East. Despite the United States’ determined intent to pivot to Asia, it has not done so. The US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 brought renewed calls for a pivot, but it was not until the 2021 Afghanistan withdrawal that the United States could refocus on the competition between great powers. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, has once again put the grand pivot on hold. With the United States distracted, China enjoys the freedom and operating space to silently achieve its aims: becoming a preeminent power in East Asia and a major power on the world stage.

China is steadily increasing its competitiveness as a global leader by executing a silent growth strategy that is steadfast and consistent. It exploits the United States’ role as a global leader that responds to, and remains mired in, crises and conflicts. These take time, resources, and attention away from Chinese activities. Consequently, the United States is the overworked night watchman and, taking clever advantage of these diversions, China has grown formidably, challenging US economic, military, and technological primacy. To counter the threat posed by a rising China, the United States needs to focus on Chinese growth, aggression, and global influence as its top national security priority.

From Most Favored to Most Feared

With the United States continuously preoccupied with hot-button global and domestic issues, China is waging a complex and unrelenting political warfare campaign with subversive and subtle tactics. Termed “gray zone” conflict, China’s activities are far from overt or obvious, and remain wholly below the threshold of armed conflict. Chinese tactics are often informational and economic versus military. And China’s soft power approaches work because the United States maintains a theory of economic interdependence—a belief that states that are economically entwined are less likely to go to war—that the Chinese leverage to target the United States and other democratic states. Americans are notoriously smitten with global interconnectedness and falling global poverty rates, both of which are a liberal theorist’s dream. China uses these concepts of globalization and international cooperation as a Trojan horse to further its economic and political offensive and as a way to ensure its strategic goals go unchallenged.

China’s campaign dates to 1979 when the United States Congress approved China’s most favored nation (MFN) trading status. MFN status created favorable trade terms for China despite its ongoing human rights violations in Tibet. And in 1998, under President Bill Clinton, China was granted permanent MFN status. Shortly after, the United States launched the Global War on Terrorism in a liberal hegemonic strategy in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Since then, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has silently advanced its strategic interests and elevated China to a position of global power.

In 2010 and 2013, as the United States wrestled with withdrawal from Iraq and a troop surge in Afghanistan, China unveiled its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The massive campaign became the centerpiece of China’s economic and diplomatic foreign policy. Preoccupied with shooting wars, the United States scarcely noticed China’s economic and information warfare that targeted the developing world and systematically began undercutting US influence and foreign assistance efforts. Since 2011, the United States has struggled with to implement its pivot to Asia, first proclaimed by President Barack Obama in an address to the Australian Parliament. Each of the last five US presidential administrations have subsequently attempted to strategically rebalance US national security priorities to Asia and China and failed.

Instead, US priorities have continued to oscillate, owing in part to Chinese surreptitiousness and in part to America’s short attention span. China’s ascension to regional hegemony means avoiding conflict is in its interest. For the United States, it is domestic politics. The first duty of every elected official is to keep the seat of power. Concerned with their own survival, politicians are constantly campaigning. Living on the two-year electoral cycle incentivizes short-term thinking over long-term planning. This internal competition for reelection steers the American people toward sound-bite foreign and national security policy. The CCP, in contrast, faces no such pressure and can therefore think long-term.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the latest crisis to attract American resources. President Vladimir Putin’s February 24 invasion and the media’s reporting on the conflict quickly thrust the European theater of war to the forefront of America’s consciousness and it has been prioritized over the threat of China. In the Donbas, Clausewitz rules the day. In Beijing, however, it is Sun Tzu. China is subduing America without fighting.

Under the Threshold

China’s objective is to solidify its place as the regional hegemon in Asia and to challenge the United States for global primacy. To achieve these ends, China must grow its economy because, as Mearsheimer reminds us, population plus wealth is the formula required for military power. Simultaneously, China seeks to rebrand its international image and convince the world that the CCP is a responsible, global-minded party. Therefore, the CCP’s tactics are subtle and subversive, bringing to mind the parable of the boiling frog: if you place a frog into a pot of boiling water, it will jump out but, if you place the frog into a pot of cool water and slowly bring the water to a boil, the frog will never notice, slowly cooking to death. The parable describes sensory adaptation—a phenomenon defined as a diminished sensitivity to a stimulus because of constant exposure to it. Drastic changes to an environment are immediately noticeable, but small changes over time are processed and adapted to, creating a new baseline from which to measure change. China’s gradual, salami-slicing tactics play directly into US leaders’ short time horizons and ensure that the American public does not see China as the primary threat demanding immediate and concerted attention until it is too late.

For example, in early May 2022, China sent eighteen warplanes into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone. It followed a fortnight later with thirty-nine aircraft—a record high for 2022. Finally, on the last day of May 2022, yet another incursion, this time by thirty Chinese aircraft. However, sorties involving these numbers of aircraft pale in comparison to the record high set for 2021, when fifty-six aircraft flew into Taiwanese airspace in October of that year. Here, the peak-end rule places focus on the highest number and the last number experienced—fifty-six aircraft is a lot, after all. Yet sensory adaptation is also at work, since these numbers, in isolation from one another, fail to show that an aggregate of 456 Chinese aircraft have flown into the Taiwanese air defense identification zone in 2022—a 50 percent increase from 2021. The frog is the last to know it is boiling.

Pawn Your Title, Keep Your Car

The CCP is also adept at using subversive economic tactics and entices foreign governments and corporate entities into honeypot-like financial deals, promising exquisite wealth with minimal risk. However, even though China’s loans come with no strings attached—unlike US loans that require states to meet certain conditions on human rights, for example—the CCP promises are negotiated in secret sessions with nondisclosure agreements, which makes it difficult to renegotiate the loans’ terms. Through the BRI, China offers economic packages to developing nations, knowing that that short-term gain the deals promise is more appealing than the long-term sacrifice of going without. This is China’s version of Stanford’s marshmallow test—a 1972 study on delayed gratification where children were each offered a choice between one small but immediate reward or two small rewards if they waited for a period of time. Many of the test subjects took the immediate reward over waiting for two. Similarly, developing states in need of financial assistance are often tempted by China’s promise of quick funding and infrastructure. But when the state cannot remit, China calls in the debt, absorbing the rights to the land, infrastructure, minerals, or ports.

One victim of China’s loan sharking is Sri Lanka. In 2002, the Sri Lankan government decided to build a new port in Hambantota and needed funding for the project. China initially offered the small nation $1.1 billion in loans and supplied Chinese contractors to carry out the work. In all, a Chinese state-owned bank loaned Sri Lanka $1.3 billion to build its new port, which opened in late 2010 and immediately lost money. Further, Sri Lanka could not make its interest payments on China’s loans. Along with loans taken out for other infrastructure development projects, Sri Lanka is now indebted to China for a total of $8 billion. Unable to pay, Sri Lanka is now facing China’s solution to its debt problem: foreclosure.

In 2014, Sri Lanka allowed China to dock a submarine in the port, causing fierce opposition from India, Sri Lanka’s northern neighbor. This led Sri Lanka to deny China’s second request to dock a submarine in 2017. In July of that year, Sri Lanka struck a deal and sold a 70 percent stake in the port to the state-controlled China Merchants Port Holdings. The deal formally handed over control of the port to China in a ninety-nine-year lease, and prompted India to discuss plans to build an airport in Sri Lanka to counter China’s influence. The tactic is a pattern for China, which “typically finds a local partner, makes that local partner accept investment plans that are detrimental to their country in the long-term, and then uses the debts to either acquire the project altogether or to acquire political leverage in that country.” Thucydides has truly come to Colombo.

The Sri Lankan port-default scheme is just one action in a series of moves that China has made to acquire ports around the globe and assert maritime dominance. China’s port plans are central to the CCP’s geopolitical goals, and will lead to Beijing challenging the United States as the world’s preeminent maritime power. China currently owns over one hundred ports in sixty-three countries, including seven of the world’s ten busiest ports. However, these numbers are just the tip of the iceberg—China has substantial financial interests that fall short of ownership in a far larger number of ports. China’s political warfare is happening everywhere and is a strategy that is employed around the globe—it identifies divisions, buys up politicians, and sets the stage for debt traps, relying on psychological warfare, media warfare, and lawfare to aid in its efforts to control key terrain and assets. The narrative the CCP wants to promote is that “China’s rise is inevitable, [so] you’re better off rising with our boat, rather than trying to cut yourself off and sink on your own.”

Another concerning development is China’s new security agreement with the Solomon Islands, which many view as a continuation of China’s efforts to obtain access to, or build, military bases to project power forward and encircle Taiwan. Beyond the first island chain in the South China Sea, China has been trying to embed itself in other islands, to further squeeze Taiwan from both sides. China’s tactics make strategic sense: by systematically positioning itself to Taiwan’s east and west, China can block resupply and constrain Taiwan’s deployment options in the event of a kinetic conflict. Recently, the Pacific island nation of Kiribati also switched recognition from Taiwan to China. Presently, discussions are ongoing over China’s desire to redevelop an old World War II US military airstrip on Kiribati’s Canton Island for “tourism”—a strategic airstrip that is relatively close to Hawaii. Additional investments in Oman’s Duqm and Pakistan’s Gwadar ports raise concerns that both may ultimately become Chinese naval bases. And, China has already added a naval base in Djibouti and announced in June 2022 its intention to build a second facility in a Cambodian port. The fact that China is collecting its proverbial lily pads through passive economic traps and political warfare instead of brute force means that it happens quietly and without the media attention paid to kinetic conflicts. And no one is stopping it.

The Hollywood Sellout

China is both a large producer and a large consumer. Chinese production centers around low-cost manufacturing and, in 2020, China was the world’s largest exporter of broadcasting equipment ($223 billion), computers ($156 billion), office machine parts, ($86.8 billion), cloth articles ($60.7 billion), and telephones ($51 billion). Conversely, China has the ability to grant or limit foreign access to its billions of consumers, which the CCP uses to its economic and political advantage. Hollywood, for example, is an industry based on viewership and China is a major market for its films. Hollywood studios recognize the economic potential of the Chinese market and have incorporated it into their business model. As a result, the relationship between Hollywood and the CCP has flourished.

In 2008, the CCP sent its propaganda executives to the University of California, Los Angeles to learn the ins and outs of the American entertainment business. Simultaneously, China enrolled foreign exchange students at US universities to better understand how to exploit the American entertainment sector. What the CCP learned is that it could engender Hollywood dependence upon the Chinese market and, therefore, hold leverage over the entertainment industry and influence American culture. Additionally, film production is expensive. A good film can be wildly successful at the box office, but a bad film can lose a lot of money. What China provides is a “surplus above subsistence” market, meaning that by virtue of mass alone, sales in the Chinese market will make up for any quality deterioration in Hollywood product. In short, Hollywood sold its ownership for a few decades of guaranteed revenue for bad films.

Today, China wields immense power over the entertainment industry simply by regulating access to its consumers. For American entertainment companies to maintain access to the Chinese market, they must comply with the content whims of the CCP. When the 1984 Cold War drama Red Dawn was updated in 2012, the script called for a villain change from the Soviets to the Chinese. Prior to release, however, Hollywood transformed the foe from China to North Korea. After an interview in which John Cena called Taiwan a country, the actor famously issued an apology in Mandarin. Marvel’s Tibetan character in Doctor Strange disappeared. The jacket worn by Maverick in the recent Top Gun sequel mysteriously lost its Taiwan flag in a 2019 trailer before, under US audience pressure, it returned in 2022. Immensely popular in Taiwan, China has not yet released the film.

The Way of Confucius

China’s Confucius Institute initiative seeks to enhance “mutual understanding and friendship” between the Chinese people and others around the globe. More than any of the tactics listed above, the Confucius Institute program exemplifies China’s soft power strategy to overturn the international balance of power. In 1987, the Chinese politburo established the National Office for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language to promote scientific, technological, and cultural exchanges with American and foreign academic institutions, in addition to its economic and trade cooperation efforts. By 2004, Confucius Institutes, a program developed by Chinese Ministry of Education–affiliated Hanban, began appearing on academic campuses. Notably, program funding is shared between the Hanban organization and the host university, with China footing much of the bill.

Initially, the CCP rolled out forty satellite sites—with the second Confucius Institute opening on the campus of the University of Maryland. By 2009, there were ninety Confucius Institutes spread across US universities with a peak of roughly one hundred institutes in 2018. Branches could be found at top American universities, like Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, Stanford, Michigan, Iowa, and George Washington. As a form of soft power, the Chinese government spends approximately $10 billion a year on its institutes and related programs to “give a good Chinese narrative.” Because the institutes are affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education, over time they received increasing skepticism over censorship of content taught, especially related to topics of individual freedoms and democracy. Accordingly, Confucius Institutes “only teach political lessons that unduly favor China.”

Soon after Confucius Institutes in the United States reached their peak numbers in 2018, the US Senate released a report on the program and, at roughly the same time, The Economist ran an article highlighting the state-run program and its cultural influence initiatives. In response, the University of Chicago, Texas A&M, and myriad others shuttered their programs. Nonetheless, over fifty Confucius Institutes remain open and operational on US campuses and additional centers are planned, in many cases due to losses in other revenue streams related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Retired University of Chicago anthropologist Marshall Sahlins reported in his 2014 pamphlet Confucius Institutes: Academic Malware that each Confucius Institute comes with $100,000 in “startup costs.” The host university is also stated to receive five similarly sized annual payments, as well as airfare and salaries for Chinese faculty brought in to teach the curriculum. America is again falling victim to its idealized notions of an economically and culturally interconnected world.

Re-Pivot to the Pivot

China is waging a silent war against the United States in the business, entertainment, and education sectors. This campaign is difficult to detect, however, as it rests underneath the visible threshold. Hovering under the “just noticeable difference” has its advantages as this allows China to grow, compete, and challenge the United States without evoking a reaction or response. The United States, meanwhile, is plagued with short-term-itis. The nature of international politics is such that there are ample emergencies to satisfy every appetite. This is problematic because the secret to the now-or-later bargain may be the ability to focus for longer periods of time. Unfortunately, this is not a feature of our democratic system. Still, the American voters have the power to reduce political oscillations and take steady aim at a longer-term foreign policy agenda. Exposing and acknowledging the CCP’s under-the-radar strategy is the first step in gaining a strategic perspective. Otherwise, the outlook is poor and the frog will continue boiling.

Michael McCormick is an international relations researcher focusing on Russia and China. He currently studies at Bloomsburg University.

Kevin Petit, PhD is on the faculty of the National Intelligence University. He received his PhD in political science from the George Washington University after retiring from the US Army as a lieutenant colonel following twenty-four years of service. His research focuses on gray zone conflict.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

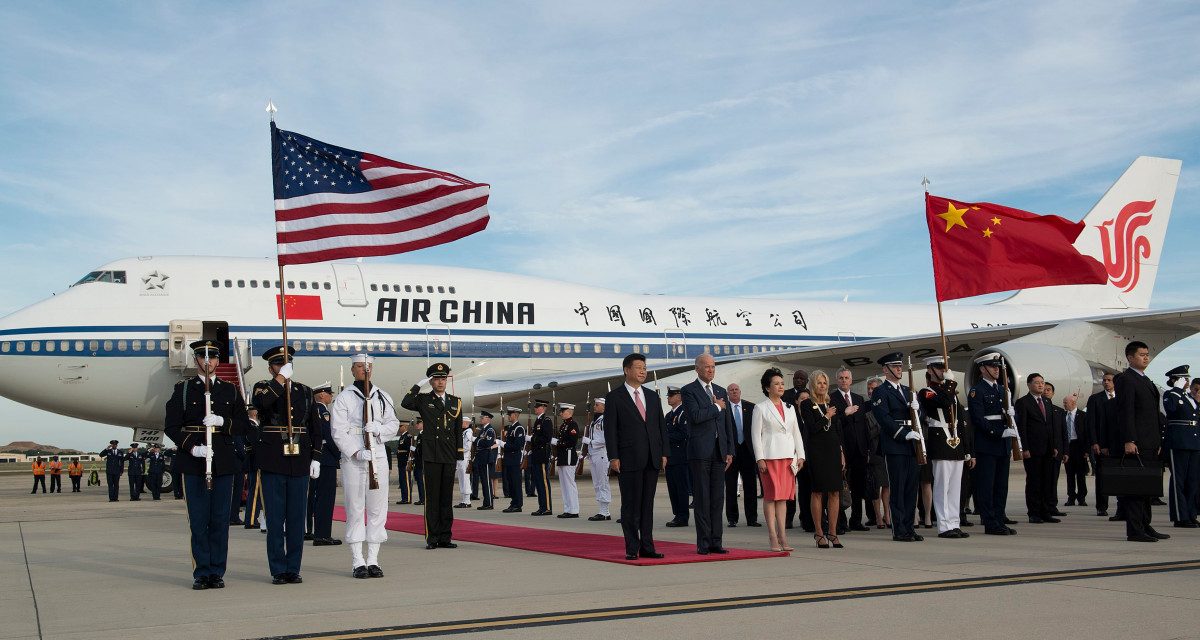

Image credit: Airman 1st Class Philip Bryant, US Air Force

This article contains some very valuable information, but it is also flawed in significant ways. Generally speaking, the assumed nefariousness of Chinese intentions is the major issue, a point of view that makes all expressions of Chinese strength devious and alarming at best. I would be delighted to respond point by point, but for brevity sake, let me just take the Confucius Institute program as an example. And for those may be skeptical of my knowledge, I direct one such program, and thus know something about them. 1. There is no 100,000 dollars start up contribution, 2. there is no Hanban, 3. there is no direct affiliation with the Ministry of Education, 4. there is no set curriculum (I devise the curriculum, and personally supervise all instruction), 5. there is no censorship or control coming from China, there is only a degree of financial support, and expertise provided…when I ask for it. The program makes it possible for hundreds of students to learn the Chinese language and about Chinese culture. Apparently, that is now a nefarious activity. It would appear that McCormik and Petit advocate for ignorance as the best way to "counter" China. I respectfully disagree.

–Paul Manfredi