Editor’s note: Stanford University is hosting a brand-new class this fall—Technology, Innovation, and Modern War. Steve Blank, who teaches the course along with Joe Felter and Raj Shah, is writing about each class session—offering Modern War Institute readers an incredible opportunity to learn about the intersection of technology and war and hear from remarkable guest speakers. Read about previous sessions here.

Class Fifteen

Today’s topic was Congress and defense with Congressman Mike Gallagher.

Our guest speaker was Congressman Mike Gallagher, a member of the House Armed Services Committee.

Congressman Gallagher is one of the leading thinkers on defense issues in Congress. He is a Princeton and Georgetown graduate; served in the Marine Corps, with deployments in Anbar province; got his PhD; joined a startup; has been reelected to his third term, representing the 8th district of Wisconsin; and is on the House Armed Services Committee.

The congressman was gracious enough to take on two roles in this class session: first, he shared his views on the future of defense, and second, he received a formal policy recommendation—our midterm assignment—as a briefing from one of our students.

I’ve extracted and paraphrased a few of key insights and urge you to watch the video of his talk.

What’s life like as a Congressman?

If you watch the news, you’d think that all of us are consumed with whatever the Twitter controversy of the day is. But there is a ton of good work going on beneath the surface, beyond what you see on TV, particularly in national security. That doesn’t get headlines, it doesn’t get a lot of attention, but it is incredibly important. As a member of the House Armed Services Committee, we pass an annual National Defense Authorization Act. It is the culmination of a year’s worth of work. And at a time when it seems like everything is divided, it represents an area of significant bipartisanship. When it comes to the big questions of the day, from a national security perspective I sense an emerging opportunity to rebuild something resembling that consensus.

The biggest misconception I had coming into this job four years ago was I thought that the dysfunction in Congress was purely a function of the people that were in Congress—that Congress was filled with charlatans, or people that were incompetent. Now certainly, there are examples of that. And certainly, there’s a lot of careerism that goes on. But Congress is also filled with a lot of incredibly smart, patriotic, well-intentioned people with unique backgrounds that just want to serve the country. And I’ve been blown away by the quality of a lot of my peers on both sides of the aisle.

That’s an opportunity for more bipartisanship. If you look at a lot of the work of the Future of Defense Task Force, some of those issues are going to be debated right now by the Biden transition team and incoming Biden foreign policy team. And I think it would be a mistake for us to go back, given how much progress we’ve made on China in general and technological competition.

What do you expect from the new administration on national security?

I think there’s a serious debate going on within the Biden national security camp about what direction to go.

There are two camps within the Biden advisory team. The first I associate with the return to the Obama-era approach, which would focus on cooperation with China. And if you want to cooperate with China, that leads you down a path where you put Taiwan relations on the back burner. You’re less likely to press hard against Chinese tech giants like Huawei. And you kind of go out of your way to be on extensively good terms with Beijing, because you want their cooperation on transnational issues, particularly environmental issues.

But if the second, more realistic camp wins out—one that looks at malign activities of competitor states, like China and Russia, and focuses on defending American influence and liberal values internationally—I think there will be a striking amount of continuity. I think the Biden administration’s spin on great power competition will be different from the Trump administration’s. That’s okay, if the point of departure is about defending our values internationally, as opposed to better competing internationally, which was the Trump administration’s core focus in the national security strategy. Ultimately, both approaches lead you in a similar direction. I think it would be a mistake for them to view everything that the Trump administration did as tainted and throw the baby out with the bathwater. Because the fact is, there has been remarkable progress made on US-China competition the last three years.

You’re still likely to come down in a similar place in terms of how you approach adversaries like the Chinese Communist Party and Vladimir Putin. And I think the Biden administration will have an opportunity when it comes to placing values at the at the center of American foreign policy. I have Democratic colleagues who are influential in the Biden camp like Tom Malinowski, who would argue for doing just that. And we’ve worked very closely on things like calling out what’s happening in Xinjiang, and similarly calling out human rights abuses at the hands of Vladimir Putin. So I think you’ll see a movement just on sort of the overall position that values-based arguments play in the national security strategy. If you talk to H.R. McMaster, he’d say that values were an integral part of the national security strategy.

Should the new administration focus on Europe or the Indo-Pacific Region?

I think Biden said that the top threat to America was Russia. I disagree with that. His team advocates for a Europe-centric approach to US foreign policy. To the extent they change the overall regional prioritization for our national security strategy and say that EUCOM (European Command) is the primary theater and INDOPACOM (Indo-Pacific Command) is secondary, I think that would be a huge mistake because there’s absolutely no comparison.

The Biden Administration and the Defense Budget

I think the new administration is going to face some very difficult budgetary choices. We just spent over $3 trillion on Coronavirus response; we’re not going to be able to continue a 3 percent increase in the defense baseline over the next two years. So there are going to have to be hard choices. And the biggest and hardest choice they need to make right away is the prioritization among the services. If you look at our National Defense Strategy, all the things that Bridge Colby talked to you about, you’d probably conclude that if you just look at our priority theater, INDOPACOM, you might notice some interesting things about that theater, notably that there’s a lot of water. Therefore, it would make sense to prioritize the Navy and the Air Force and not prioritize growing the Army. That’s a huge choice they’re going to have to make right away.

Trading Climate Issues for Security Issues

The Biden administration wants to prioritize environmental issues in the way that the Trump administration didn’t. I think Biden already announced his intent to rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement. I think it would be a mistake to subordinate our security issues, particularly those with China, to the demands of cooperating on environmental issues. However, I think there’s room to make a smart investment in carbon-capture technology and nuclear micro-reactor technology. I have a bill with Chuck Schumer and Ro Khanna, a progressive Democrat. It would be the biggest investment from the federal government in research and development since the end of the Cold War, and a lot of that would be in clean energy technology.

Opportunities on Trade, Section 232 Tariffs, and Allies

You can’t pick a trade fight with our friends at the same time you’re trying to pick a trade fight with China. You could immediately bring some of our disaffected friends into the fold, particularly if they continue to move in our direction when it comes to 5G, which is probably the most important disagreement we’ve had with some of our European allies.

There’s an opportunity to clean up any lingering disputes with allied countries when it comes to Section 232 Tariffs—the tariffs we placed on steel and aluminum. There’s a dissertation waiting to be written about the nature of 232 tariffs and the constitutional problems with Congress giving up its ability to regulate commerce with foreign nations to the executive branch. It created a situation in which the president was able to claim that we face a national security threat from Canadian steel and aluminum and effectively impose a tax on the American people. So let’s resolve the Section 232 disputes—I’ve opposed them from the start—and at the same time maintain pressure on the Section 301 investigations, which are the investigations into unfair Chinese trade practices.

There are economic opportunities for the incoming Biden team. I think there’s just an obvious slam dunk with the UK, now that they’re withdrawing from the European Union, in the form of a free trade agreement with them, as well as a bilateral trade agreement with Taiwan. The reason that the US Trade Representative didn’t want to pursue a trade agreement with Taiwan was because they didn’t want to screw up the phase one trade deal with China.

The Future of 5G

For all the criticism of the Trump administration’s neglect of allies, the fact is, we’ve recently had some incredibly important diplomatic wins—for examples when it comes to convincing the UK to get on the same page with us with respect to Huawei or shifting the Huawei/ZTE 5G debate in certain European countries like Germany. We have a long way to go. But it does seem like the concerted effort from the executive branch and the legislative branch to send a signal, at least to our closest allies, our Five Eyes allies, that we need to have the same basic principles when it comes to future control of the internet and 5G internet technologies.

I think it’s critical, at least on 5G, to be in the same position with our allies. But I would say for the last four years we’ve purely been playing defense. In other words, we’ve been going around the world saying Huawei is bad, ZTE is bad. See, look at all this stuff. We’re declassifying all this evidence. And that’s good, we had to do that. And it requires some tough conversations.

The next phase of this involves some sort of offensive-minded effort in concert with our allies to cooperate better on these technologies. To form a digital development fund to coordinate the R&D and the distribution pathways with our likeminded partners. Without reinventing the wheel of existing international efforts, America can take the lead by launching a coalition of countries dedicated to finding a coordinated solution, particularly when it comes to 5G, that can not only compete on quality with Chinese state-owned or sufficiently state-backed enterprises, but also compete on price.

Reshoring Manufacturing and Economic Decoupling from China

I think that some form of selective economic decoupling from China is inevitable and necessary. And you’re going to see efforts to selectively decouple when it comes to our capital markets—to make sure that if Chinese companies list in US markets, they have to follow the same reporting and transparency requirements as US companies. They’re going to see it in key technology areas, not just 5G, but AI, rare earths, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals. I think there’s going to be a serious effort to reshore manufacturing, or perhaps revitalize Puerto Rico as a hub for manufacturing of advanced pharmaceutical ingredients. You’re going to see it reflected in a lot of different areas.

Congress and Long-Term Planning

It’s very hard for Congress to do long-term strategic planning. We’re not optimized as an organization to look beyond two years. And sometimes it feels like we’re just looking two weeks at a time or two days.

I pay attention to this stuff. I work hard to understand it. I have an academic and a professional background in it, which I think gives me a little bit of advantage. But I feel like I’m just scratching the surface because there’s no time to really dig into the bureaucratic labyrinth that is the Pentagon.

Why the status quo wins out, why the primes are so good at defending their territory, it’s not laziness on the part of members of Congress. It’s just that you have so many demands on your time and the demands of reelection. It’s hard to carve out a half hour of my day to devote to serious defense work just because of the nature of being a member of Congress. And that’s a problem because it’s really Congress’s role. If you look at the history of some of our autonomous drone systems, it was Congress poking the Pentagon to get over their intransigence at the early stages. It requires the legislative branch to get in the game to force the Pentagon to do some things it often doesn’t want to do.

While it’s impossible to predict all the technologies that will dominate the future, if you talk to younger members of the Armed Services Committee, some things are obvious. I think everyone agrees that we have to make an increased investment in AI, and the future will inevitably involve a lot more unmanned systems.

For example, I work a lot on naval issues. If you think about how we’re going to grow the future of the Navy, it’s obvious that we’re not going to be increasing the number of carriers we have from eleven to fifteen. In fact, it’ll probably be a glide path, down to nine at some point. And then we’ll grow the fleet with smaller ships (i.e., small surface combatants) and then unmanned systems—both large, unmanned surface combatants as well as unmanned underwater vessels.

And if you look at the Marine Corps commandant’s planning guidance, which I think is the most innovative thing that’s been written by any military service in the last decade, that’s exactly what he’s recognizing. He’s the only one I’ve seen so far that’s been willing to say, “We are not going to invest in certain legacy systems like big amphibious ships that are optimized for doing a joint forced entry operation like Marines did back in World War II in the Pacific. Instead, we’re going to focus on fielding small teams of Marines, who can operate unmanned systems throughout the first and second island chain. Having the logistical infrastructure to constantly move them around to complicate our enemy’s decision-making cycle. Figuring out the basing agreements with our allied countries, so we can host missile systems there.” I think he gets the mix right.

Personnel Costs and the DoD Budget

All of this is bound up in a bigger budget discussion. You can scrape together an extra $50 million or $100 million to invest in robotics, AI, and hypersonics but If you look at the overall budget, what’s costing us more and more money, it’s human beings. In other words, if you compare the Reagan buildup in the 1980s, in the heady days of the 600-ship Navy, in real dollars adjusted for inflation, we spent more money during the Obama eight years then we did during the Reagan years.

And it’s not because our ships got more exquisite and fancier, though they did. It’s primarily because human beings got more expensive. The military has the same problem that the rest of society has—funding health care and retirement costs. And that’s a very difficult problem to solve. Theoretically, unmanned allows you to have a similar impact with less human beings. But you’re still going to have a lot of human beings involved in the business of defending the country. I just bring that up to say the biggest and hardest choices that DoD needs to make have nothing to do with cutting-edge technology. They have everything to do with healthcare costs, retirement costs, and the cost of training human beings and making sure they’re ready to fight.

The Military Personnel System

The biggest problem I saw when I was in the military is really that the best and brightest officers of my generation (myself excluded) left—usually at the O-3 level. In part it wasn’t a pay thing. It wasn’t that they wanted to go to GSB and then make a bunch of money doing venture capital in Silicon Valley. It was more about flexibility. They wanted the Marine Corps to meet them halfway in terms of, “Hey, can I pursue civilian graduate school and I’ll pay the Marine Corps back on the back end? I don’t want to have to spend a year at Expeditionary Warfare School because it doesn’t make any sense to me.” And it was just more of a career flexibility and management thing. I think this is something we grappled with extensively on the Future Defense Task Force: How do you retain the best and the brightest? How do you attract the best and the brightest?

I think if you retain qualified officers and enlisted military service members throughout their career, you’ll start to get more innovative thinking at the top ranks when they become field-grade officers, and when they become general officers. And you’ll have less of a status quo military industrial complex.

Another area where we’ve given the Pentagon enormous latitude is to reach into private industry and make somebody a colonel or a lieutenant colonel if they have the appropriate skill set, and they really have been loath to use that authority.

Acquisition, Primes, Requirements, and DoD

We have a very brittle defense industrial base. It’s highly concentrated among five or six companies. I think there’s only been two defense-related startups that have had a valuation north of a billion dollars in the last couple decades: SpaceX and Palantir. That’s because we build moats around these industries. And there’s a bunch of special interests that advocate for the status quo, and it becomes very hard for Congress to change anything.

Now we’ve tried. We’ve tried in the form of giving special acquisition authority to the services. Honestly, if you look at the US Code when it relates to defense provisions, we don’t really need to give new authority to the services to allow them to experiment and invest in certain technologies and make bets on small and medium-sized companies. We’ve given them a ton of authority. But there’s a general risk aversion among the services and almost an unholy alliance between the general officer and flag officer class and the primes. Because general and flag officers, when they retire, go and work for the primes and get paid a million dollars a year as a consultant for Boeing or Lockheed. So there’s a “swampy” aspect to all of this that precludes innovation or a risk-taking mindset.

The Goldwater-Nichols Act governs the requirements processes for the services. Today, for example, the Navy says, “we need to do X. And here’s our strategy for doing X.” And all these documents go bounce around the Department of the Navy. We need to change that entire process. Because the result is the services generate requirements that do not align with the National Security Strategy. Or they’re just published prior to those documents, or without taking into account changes those documents make. It’s a totally incoherent strategy process that doesn’t drive our budget choices and allows the status quo to win out and legacy systems to dominate.

As an example, we have a shipyard in northeastern Wisconsin, Fincantieri Marinette Marine, where we built the Littoral Combat ship. The Littoral Combat ship was supposed to be the ship of the future for the Navy. You can Google “Bob Work LCS”—he wrote a great white paper on how the Littoral Combat ship went awry. And it was really a story of the Navy just getting too ambitious with its requirements and trying to do too much with one ship. They constantly changed requirements, which then screwed up the manufacturing, making it extremely complicated.

I worry that we get too enamored with the new technology and the next big thing and create these hyper-exquisite platforms that are extraordinarily difficult to build, let alone operate and maintain, when sometimes a simpler, less technologically advanced approach might do just as well.

There are also some huge opportunities they have now that we’re no longer bound by the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty. Because we can field missile systems that we already have, that have ranges between 500 and 550 kilometers that can do things that otherwise require a destroyer or a big, fancy expensive ship to do.

How do we stop special interest groups in the military industrial complex from influencing Congress to make decisions that are perhaps better for business but maintain the status quo?

It comes down to the way in which the Pentagon awards money. The Pentagon needs to stop making very small and insignificant bets on a variety of small or midsize companies that can never make that next step to becoming a prime. They need to start making bigger bets on a smaller subset of non-prime companies. That’s one way you could start to get less of a military industrial complex culture.

I wonder if there’s not some sort of ethics reform or drain-the-swamp proposal that could be applied to the Pentagon without unleashing some unintended consequences. I’ve long thought it’s a good idea for members of Congress to be prohibited from lobbying for the industries that they oversee in Congress for a period—I prefer for a lifetime, but I’d take five years. That that seems like a sensible, drain-the-swamp proposal that myself, Ro Khanna, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez could get behind.

And I wonder if you couldn’t have a similar prohibition when it comes to general officers and flag officers. Or at least extend the cooling-off period, so they can’t immediately go and collect a paycheck from some of these companies. Now that may sound naive and populist to some of your more cultured teachers, but you’ve got to do something about it at the end of the day. Otherwise, you won’t get any change.

Advice to Our Students

I profited from the advice and mentorship of a lot of people, including your professor Raj Shah. So I’m happy to pay that forward. I was where you guys are a few years ago, just slugging it out in grad school. And you never know when you’re going to be the person making big decisions. Whether it’s as a legislator or member of the executive branch.

And so, I would encourage you guys to keep pursuing your current policy studies. You’ll find yourself in a position where you can make a real impact very quickly. And if you can write well, and if you can work well with others, you’ll you have limitless potential.

Watch the video of Congressman Gallagher’s talk below.

If you can’t see the video click here.

Class Sixteen

Today’s topic was acquisition, sustainment, and modern war.

Some of the readings for this week included: “Defense Acquisitions: How DOD Acquires Weapon Systems and Recent Efforts to Reforms the Process,” “Defense Primer: Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) Process,” “Acquisition Reform in the FY2016-FY2018 National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs),” “Defense Primer: Department of Defense Contractors,” and “Defense Primer: U.S. Defense Industrial Base.”

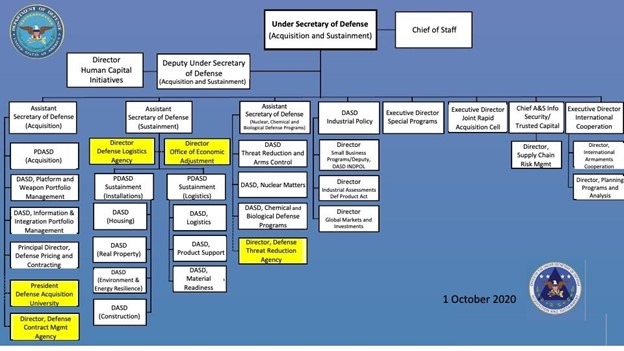

Our guest speaker was the Honorable Ellen Lord, the under secretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment. She is responsible for acquisition; developmental testing; contract administration; logistics and materiel readiness; installations and environment; operational energy; chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons; the acquisition workforce; and the defense industrial base.

Prior to this appointment, Ms. Lord served as the President and Chief Executive Officer of Textron Systems Corporation, a subsidiary of Textron Inc., leading a multi-billion-dollar business with a broad range of products and services supporting defense, homeland security, aerospace, infrastructure protection, and customers around the world.

I’ve extracted and paraphrased a few of Ellen Lords key insights and urge you to read the entire transcript here and watch her video.

Progress in Modernizing the Defense Acquisition System.

Everything we do here at the Department is under the framework of our National Defense Strategy, or NDS. Acquisition and sustainment is focused on supporting all three lines of the national defense strategy. They are:

- Restoring military readiness as we build a more lethal force.

- Expanding and strengthening alliances and partnerships.

- Bringing business reform to the Department of Defense.

Strengthening Our Supply Chain

Under the first line of effort, lethality, we’re focused on addressing supply chain fragility. The nature of today’s near-peer or peer threat is not always kinetic. One of the ways our adversaries try to gain the advantage is by attacking our supply chain through methods like fraud, introduction of counterfeit materials, control of raw materials, cyber and intellectual property attacks, denying access to strategic materials and rare earth minerals, and finding ways basically to undermine our free market system.

The United States is reliant on a global supply chain for our goods, systems, and services. In most instances, this is really very positive. We’re enriched by investments from other countries, which often helped to build infrastructure that supports a variety of industries. However, we really need to remain vigilant about reliance on adversarial countries when it becomes to our defense industrial base and our national security systems. Should our adversaries choose to restrict supplies, it’s really possible that the department would struggle to find, test, and qualify replacement sources if they even exist. So, the DoD report that we wrote in 2018 in response to Executive Order 13806 highlighted reliance on foreign suppliers, including China, for critical materials such as rare earth elements and microelectronics.

For example, China has an 80 percent market share in rare earth elements, as well as a significant market share in manufacturing value-added goods containing those elements, such as electric motors and consumer electronics. Rare earth elements are integral to the US military and to the national infrastructure and economy. They’re used in a wide variety of applications, ranging from guidance systems for missiles and space launch vehicles to electric vehicles and sophisticated medical instrumentation.

Expanding and Strengthening Alliances and Partnerships

In accordance with the second line of effort in the NDS, strengthening alliances, we’re actively working to better harness defense trade as a strategic tool to advance national security interests. We are tracking thirty-seven initiatives across DoD focused on four main areas: designing in exploitability early in programs; facilitating technical release ability; capturing market space (versus Russia, for instance); and increasing industrial capacity.

And in addition to strengthening our interoperability with allies and partners. Reforms in each of these areas will strengthen the foreign military sales process. It will enhance the defense industrial base’s global competitiveness, and it will increase our supply chain export capability. As we move into fiscal year 2021, an effort we call defense trade modernization will help both DoD as well as the interagency process to streamline and allow the United States to more rapidly export technology in order to drive this interoperability because we don’t fight alone when we fight. It will also help to sustain our domestic industrial base.

Business Reform: The 5000 Series

In support of the NDS’s third line of effort, reform, our organization is committed to enabling an acquisition environment designed to deliver warfighting capability at the speed of relevance, versus one that’s defined by bureaucracy. One of my team’s most significant accomplishments has been rewriting what we call the 5000 series—the overarching policy on DoD acquisition—to focus on what I call creative compliance so that acquisition professionals can design acquisition strategies that minimize risk.

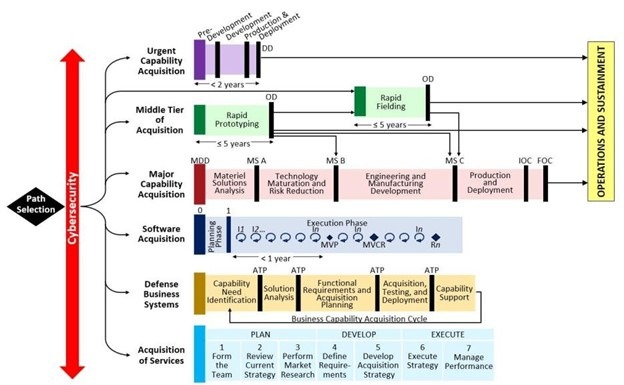

The 5000 rewrite achieves that objective by decomposing a large policy document into six clear and separate pathways that we call the adaptive acquisition framework, or AAD. Each pathway is tailored to the unique characteristics of the capability being acquired. The six pathways include urgent capability acquisition, middle tier of acquisition, major capability acquisition, software acquisition, defense business systems, and acquisition of services.

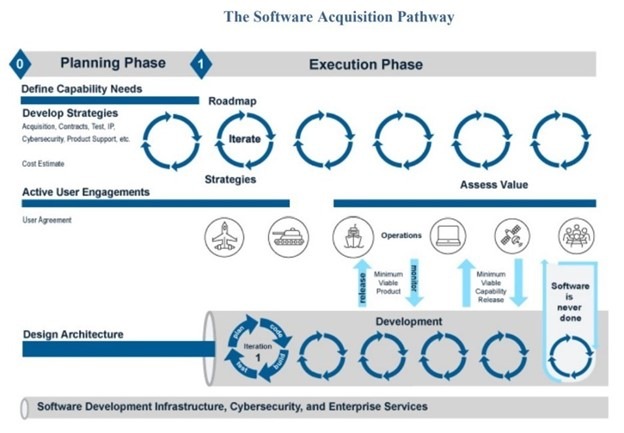

The software acquisition pathway is the newest pathway in the adaptive acquisition framework. Given that software is central to every major DoD mission and system, we need to acquire and deliver software with much greater speed, agility, and cybersecurity. The software pathway is built on commercial principles that really enable innovation and rapid delivery in response to conditions of uncertainty. We have rapidly changing user needs; we’ve got disruptive technologies and threats on the battlefield. The policy tailors and streamlines acquisition and requirements, processes, reviews, and documents, to adopt a modern development practice, like agile and DevOps, or DevSecOps.

It’s a substantial departure from the department’s usual way of doing business, removing procedural bottlenecks and regulatory bureaucracy. Programs are really pushed to embrace the goal of delivering capabilities on a much faster cycle time in one year or less, while emphasizing and ensuring cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity is Integral

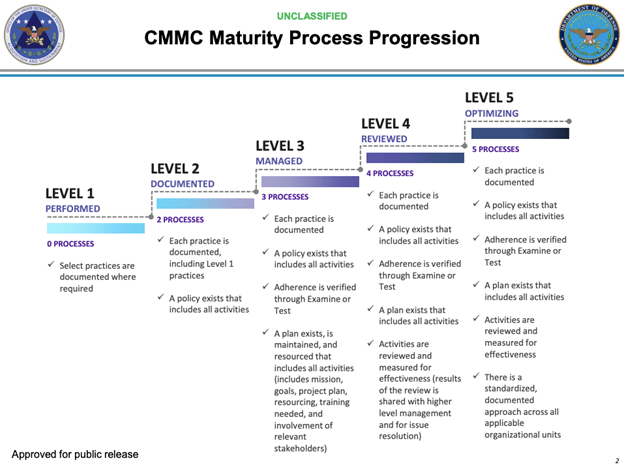

One of the subordinate functional areas is cybersecurity, which is a foundational aspect of any acquisition that cannot be traded for cost, schedule, or performance. To ensure cybersecurity is also foundational for our partners in industry, the department created the Cybersecurity Maturity Model certification, which we call CMMC. It’s scalable, auditable, and repeatable—a cybersecurity standard that industry partners will be required to obtain, depending on the level of cybersecurity required in a specific contract.

The cyber security model certification DFARS rule—the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation standards that we live by—was recently posted on the US Federal registry as an interim rule. The public’s going to be able to comment on the rule for sixty days. And then at the end of the sixty-day period, the rule will go into effect. Therefore, it will require that by October 21, 2025, all DoD contracts will have some level of CMMC. Now, I think of this as we think of ISO quality. It’s the same kind of idea.

Risk Management Tools

The department launched a pilot program with commercial risk management tools—the one we use is called Exigers DDIQ—to really assist with rapidly identifying reputable vendors and vetting the sources of their supplies. We need to know who is in our supply chain, who the beneficial owner is, not just that we’re dealing with a shell company. This tool is fed into our department’s ADVANA analytics platform. And we’re able to provide supply chain illumination that is now essential to the department’s execution of all US Defense Production Act authorities, to be able to make sure we increase capacity and throughput in our supply chain. This also helps us make sure that we not only help the Department of Defense, but we work with all of our partners to acquire vital personal protective equipment and medical supplies in response to COVID-19.

Our enhanced understanding and rapid vetting of the supply chain has helped mitigate the award of fraudulent contracts to opportunists. And there are many, many out there. And it ensures the effective use of the CARES Act funding we’ve received from Congress.

What do you consider the most important reforms initiated under your leadership today?

One is the fact that we have made acquisition much simpler to understand and use. Instead of having this big book that you read through and use like a pilot’s checklist, we now have the acquisition process, broken into different pieces that can be adapted.

Out of all of those pieces, I think the most significant accomplishment is the software pathway. We’ve basically said that our major weapon systems are hardware enabled but software defined. And we need to make sure we continually evolve that software, from development to production to sustainment. It’s all a continuum. And we actually are really excited to have been able to work with Congress to define some pathfinder projects for a “software color of money.” Because previously, we spent so much time on administrivia—the very important administrivia to make sure we were legally compliant with colors of money. This is going to be able to unleash our business processes to keep up with technical innovation.

What are the biggest challenges and opportunities going forward for further reform?

I think it’s really communicating with industry, to understand middle-tier acquisition, how we no longer need clearly defined requirements. We can basically try to define a capability and see the art of the possible. To make sure that industry understands how they can work with contracting professionals to get on contract. And then also to teach our contracting workforce what we have for capability and really unleash them to innovate.

I always think that technical innovation is way sexier and easier to do for all the obvious reasons than business innovation. Because people are afraid they’re going to break the law and go to jail, be hauled up in front of the news, or get pulled up onto the Hill for a hearing that can be lots of fun. What we have to do is show that our acquisition professionals, our business professionals, can make a huge difference to the warfighter. No kidding, they can get capability in warfighters hands much more quickly.

Many argue that maintaining our technology edge is less about technology and more about the speed in which it can be identified and deployed. Would you agree with this assessment?

How do you quickly apply it to the warfighting gaps we have? My whole team works very closely with the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. John Hyten. His responsibility through the JROC is to define requirements for the warfighter.

My responsibility through our acquisition process is to get it there quickly. And the challenge is the valley of death we have between development of cool technical things and applying them in a way that means the warfighter can use them. So we like to work on the art of the possible. How do we get going? How do we enable that technical collaboration to meet the needs of the warfighter?

How would your organization increase collaboration between industry and government, especially at the startup and small-company level?

Most of our innovation comes from small businesses. It’s absolutely vital to us at the Department of Defense. I believe regardless of where you work, and what your mission is, everything comes down to communication. Early on, I knew that my team could only communicate and meet with so many people. So I decided we would use the industry associations as our force multiplier. To echo and amplify what messages we have. But just as importantly, if not more importantly, is for us to listen to what industry needs.

So what we do is, I bring about fifteen people, and we’re doing this virtually now, just as well as we did it in person, quarterly, working with three industry associations. They pulled together about fifteen or so CEOs. They develop the agenda. I bring our service acquisition leads, I bring a number of A&S individuals, and we talk with industry about what their challenges are, what they’re doing. I also bring the big primes in—one company, once a month, with their senior leadership teams, my senior leadership team, and again, service acquisition representatives, and we talk about the issues.

What’s changed in how you’re preparing our acquisition professionals for these new ways of doing business?

We used to lock them down at the Defense Acquisition University for two or three weeks and put our finger on the transmit button and lecture in what I’d call like a thirty- of forty-year-old way. We’ve changed that. We’ve been totally virtual since March. But more importantly, we do lots of podcasts in which, instead of taking what I consider to be the very dry policy, we do interviews with the program executive officers and program managers and get them to tell stories about the acquisition problems they’ve had and how they’ve used some of the authorities we have. Because again, I want that creative compliance. People are so worried about doing something wrong, that they rather do nothing at all. That isn’t helping us.

So it’s very different—a lot of real-time presentations, a lot of podcasts, a lot of self-service type of work. We also actually licensed from TED Talks what we call TEDx DAU. And we just finished with our second round of TED talks on defense acquisition. And it’s kind of acquisition at the edge.

How is the purchase of new weapon systems technologies coordinated with the development of new doctrine or new operational concepts?

The NDS tells us that we are pivoting from violent extremist organizations to peer threats, like what we see around the second island chain with China. So what we have to do is change our warfighting capability. We are working very closely with the Joint Staff and the services as we develop that new doctrine. It’s something we do on weekly meetings with the SecDef. Dynamic force employment, for instance—we are deploying ships and aircraft that just show up different places a little bit more surprisingly.

What we’re doing is listening to that voice of the customer, the warfighters, about a range of things. What electronic warfare capabilities do they need? What are the all-domain command-and-control systems that they need, now that we are truly an interoperable force? And we’re working closely with the Joint Staff through the JROC with Gen. Hyten. So it’s taking that technology and applying it where needed with lots of cycles, lots of iterations, back and forth.

Do you think Anduril’s model, where a company develops a product on their own dime and then sells it to DoD versus DoD funding the development is the future of defense tech procurement?

I think there is very much a place for the Anduril-type model, as well as the traditional companies. I think we need a whole spectrum, because a company is not going to build an aircraft carrier or a fighter jet or a large satellite on their own. It’s just too complex, too cumbersome. But smaller options, I think, are very much what we want to see. We want to see those developments. We want to get them in the hands of the warfighter as soon as possible.

That’s where we’re using “other transaction authorities” to get going on that. That’s what DIU does. We’re using middle tier of acquisition to rapidly field prototypes and new production.

How does DoD ensure operational security and its acquisitions when there’s such a vast range in diversity of corporate contributors to the national security ecosystem?

OPSWC, as we call it, is incredibly important. On one hand, one of my prime focus areas has been cybersecurity of the defense industrial base. That’s why we rolled out CMMC.

So that was huge, making sure that the infrastructure of companies are adequately protected. And again, scaling. It’s different if we buy combat gear—you know, boots or clothing—versus if we’re buying a fighter jet. You need a different level of security. But also, what we’re doing with our new 5000 rewrite, one of the functional areas was cybersecurity. We are writing in cybersecurity standards to how you design new systems.

We also spend an enormous amount of time with NSA and Cyber Command, understanding the exquisite intelligence we get on what adversaries are trying to do to our weapon systems. And we are going back and continuing to harden the already fielded systems and designing cybersecurity into new systems. And then, of course, we are looking at mergers and acquisitions.

I spend quite a bit of my time with the Committee on Foreign investment in the United States, CFIUS, which was firmed up by FIRRMA. Bottom line, when there is a national security threat we can block transactions acquisitions. And now with FIRRMA we can block acquisition of real estate adjacent to critical national security spots, and we can also intervene in joint ventures.

Some students in our class aspire to public service. Any advice and recommendations on how they might approach this?

I spent thirty-three years in industry before coming into government. And this government job is by far the most fascinating job I’ve had. I was very fortunate to do some things in industry that I’m proud of and that I think were significant, but there is just so much you can do in government.

So on a fundamental level, I would say connect with people. We have rather Byzantine hiring processes. I didn’t even know that USA Jobs existed before I came on to the federal government. But that’s where we advertise all of our jobs. But you have to connect with people. And you need to talk about what you’re interested in doing. Reach out to someone currently in government and talk a little bit about what generally they’re interested in and what they would like to do. Because you don’t know what you don’t know. But you’ve got to start a conversation.

I will tell you, you’re never going to make a lot of money working in government; however, particularly at junior levels you will be exposed to so much more than you could be in the same amount of time in industry. And I’d say a one- to three-year stint would be incredibly enriching for your background, regardless of what you do with the balance of your career. I fantasize about getting people back in for one to two years that perhaps served for seven to ten years, then went out to industry. I would just love to get some logisticians from Southwest or a trucking company or Amazon to come and work with us. Because what we do at the Defense Logistics Agency, it’s eye watering. It’s just unbelievable. So I’d say communication, communication, communication.

When I grew up my father was a lawyer and had served in the Army in World War II. But we never talked about what it was to serve. And not only is it really incredible to be part of something much bigger than just you, it’s amazing how much impact you can have and how much you can see and learn.

Read the transcript of Ellen Lord’s talk and watch the video below.

If you can’t see the video click here.

Steve Blank is the father of modern entrepreneurship, an entrepreneur-turned-educator, and founder of the lean startup movement. He is an adjunct professor at Stanford and a senior fellow for entrepreneurship at Columbia University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Martin Falbisoner