Editor’s note: Stanford University is hosting a brand-new class this fall—Technology, Innovation, and Modern War. Steve Blank, who teaches the course along with Joe Felter and Raj Shah, is writing about each class session—offering Modern War Institute readers an incredible opportunity to learn about the intersection of technology and war and hear from remarkable guest speakers. Read about previous sessions here.

Class Nine

Today’s topic was autonomy and modern war.

Some of the readings for this class session included DoD Directive 3000.09: Autonomy in Weapons Systems, “Defense Primer: U.S. Policy on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems,” “International Discussions Concerning Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems,” “Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2),” “A New Joint Doctrine for an Era of Multi-Domain Operations,” and “Six Ways the U.S. Isn’t Ready for Wars of the Future.”

Autonomy and The Department of Defense

Our last two class sessions focused on AI and the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (the JAIC,) DoD’s organization chartered to insert AI across the entire Department of Defense. In this class session Maynard Holliday of RAND describes the potential of autonomy in DoD.

Maynard was the senior technical advisor to the under secretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics during the previous administration. There he provided the secretary technical and programmatic analysis and advice on R&D, acquisition, and sustainment. He led analyses of commercial independent research and development programs and helped establish the department’s Defense Innovation Unit. And relevant to today’s class, he was the senior government advisor to the Defense Science Board’s 2015 Summer Study on Autonomy.

Today’s class session was helpful in differentiating between AI, robotics, autonomy, and remotely operated systems. (Today, for example, while drones are unmanned systems, they are not autonomous. They are remotely piloted/operated.)

I’ve extracted and paraphrased a few of Maynard’s key insights from his work on the Defense Science Board autonomy study, and I urge you to read the entire transcript here and watch the video.

Autonomy Defined

There are a lot of definitions of autonomy. However, the best definition came from the Defense Science Board. They said, “To be autonomous, a system must have the capability to independently compose and select among different courses of action to accomplish goals based on its knowledge and understanding of the world, itself, and the situation.” They offered that there were two types of autonomy:

- Autonomy at rest – Systems that “operate virtually, in software, and include planning and expert advisory systems.” For example, in cyber, where reactions must take place at machine speed.

- Autonomy in motion – Systems that “have a presence in the physical world.” These include robotics and autonomous vehicles, missiles and other kinetic effects.

A few further key definitions:

AI refers to computer systems that can perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. They sense, plan, adapt, and act, and include the ability to automate vision, speech, decision making, swarming, etc. This provides the intelligence for autonomy.

Robotics involve kinetic movement with sensors, actuators, etc., for autonomy in motion.

Intelligent systems combine both autonomy at rest and autonomy in motion with the application of AI to a particular problem or domain.

Why Does DoD Need Autonomy? Autonomy on the Battlefield

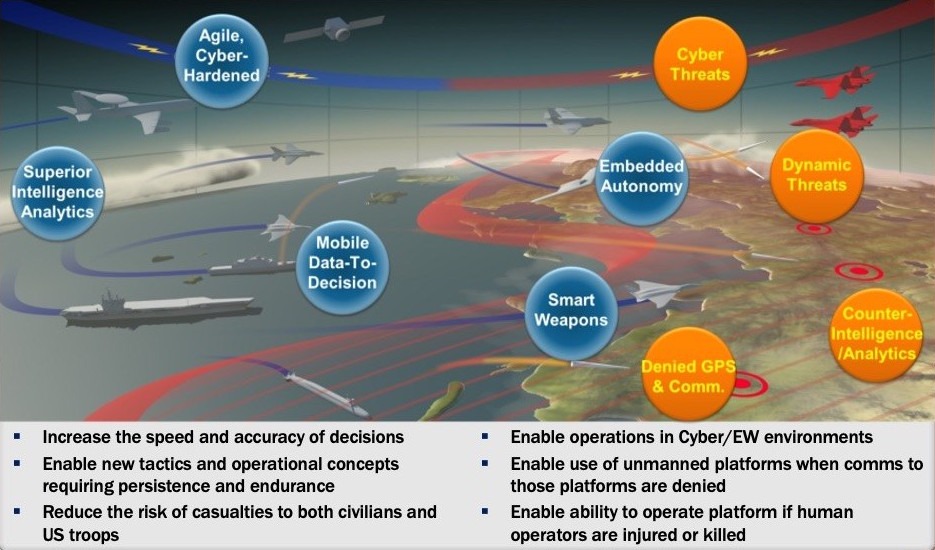

Over the last decade, DoD has adopted robotics and unmanned systems, but almost all are “dumb”—pre-programmed or remotely operated—rather than autonomous. Autonomous weapons and platforms—aircraft, missiles, unmanned aerial systems, unmanned ground systems, and unmanned underwater systems are the obvious applications. Below is an illustration of a concept of operations of a battle space. You can think of this as the Taiwan Strait, or near the Korean peninsula.

On the left you have a joint force: a carrier battle group, AWACS aircraft, and satellite communications. On the right, aggressor forces in the orange bubbles are employing cyber threats, dynamic threats, and denied GPS and comms (things we already see in the battlespace today.)

Adversaries also have developed sophisticated anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. In some of these environments human reaction time may be insufficient for survival.

Autonomy can increase the speed and accuracy of decision making. By using autonomy at rest (e.g., cyber, electronic warfare) as well as autonomy in motion (e.g., drones, kinetic effects), you can move faster than your adversaries can respond.

Autonomy Creates New Tactics in the Physical and Cyber Domains

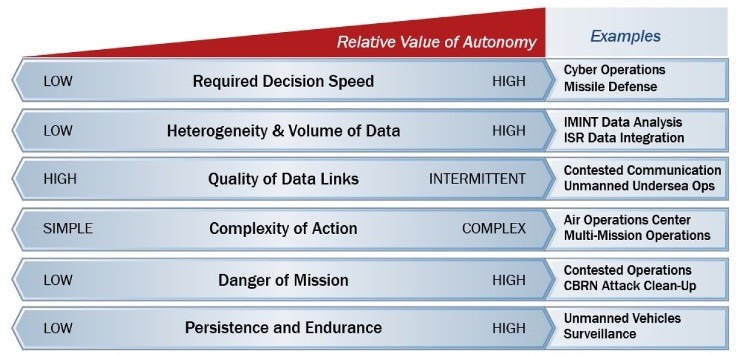

Combatant commanders asked the Defense Science Board to assess how autonomy could improve their operations. The diagram below illustrates where autonomy is most valuable. For example, on the left side of the spectrum in each row—when, for example, the required decision speed is low—you don’t need autonomy. But as that required decision speed, the complexity of an action, volume of data, and danger increases, the value of autonomy goes up. In the right column you see examples of where autonomy provides value.

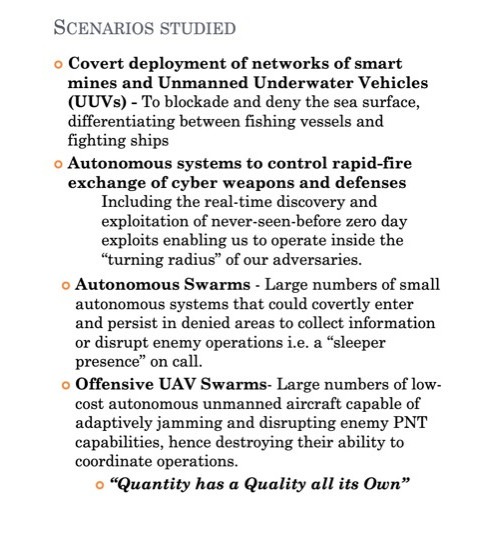

The Defense Science Board studied several example scenarios.

Some of these recommendations were invested in immediately. One was the DARPA OFFSET (OFFensive Swarm Enabled Tactics) program run by Tim Chung. Another DARPA investment was the Cyber Grand Challenge, which provided seed funding for systems able to search big data for indicators of weapons of mass destruction proliferation.

Can You Trust an Autonomous System?

A question that gets asked by commanders and noncombatants alike is whether an autonomous system can be trusted. The autonomy study specifically identified the issue of trust as core to the department’s success in broader adoption of autonomy. Trust is established through the design and testing of an autonomous system and is essential to its effective operation. If troops in the field can’t trust that a system will operate as intended, they will not employ it. Operators must know that if a variation in operations occurs or the system fails in any way, it will respond appropriately or can be placed under human control.

DoD Directive 3000.09 says that a human has to be at the end of the kill chain for any autonomous system now.

Postscript: Autonomy on the Move

A lot has happened since the 2015 Defense Science Board autonomy study. In 2018 DoD stood up a dedicated group—the JAIC—to insert AI across the department.

After the wave of inflated expectations, completely autonomous systems to handle complex, unbounded problems are much harder to build and deploy than originally thought. (A proxy for this enthusiasm/reality imbalance can be seen in the hype versus delivery of fully autonomous cars.)

That said, all US military services are working to incorporate AI into semiautonomous and autonomous vehicles—in other words, what the Defense Science Board called autonomy in motion. This means adding autonomy to fighters, drones, ground vehicles, and ships. The goal is to use AI to sense the environment, recognize obstacles, fuse sensor data, plan navigation, and communicate with other vehicles. All the services have built prototype systems in their R&D organizations, though none have been deployed operationally.

A few examples:

The Air Force Research Lab has its Loyal Wingman and Skyborg programs. DARPA built swarm drones and ground systems in its OFFSET program.

The Navy is building large and medium unmanned surface vessels based on development work done by the Strategic Capabilities Office. It’s called “Ghost Fleet,” and its large unmanned surface vessels development effort is called Overlord.

DARPA completed testing of the “Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel” prototype, dubbed “Sea Hunter,” in early 2018. The Navy is also testing unmanned ships in the NOMARS (No Manning Required Ship) program.

Future conflicts will require decisions to be made within minutes or seconds compared with the current multiday process to analyze the operating environment and issue commands—in some cases autonomously. An example of autonomy at rest is tying all the sensors from all the military services together into a single network, which will be JADC2 (Joint All-Domain Command and Control). (The Air Force version is called Advanced Battle Management System).

The history of warfare has shown that as new technologies become available as weapons, they are first used like their predecessors. But ultimately the winners on the battlefield are the ones who develop new doctrine and new concepts of operations. The question is, which nation will be first to develop the autonomous winning concepts of operation? Our challenge will be to rapidly test these in wargames, simulations, and experiments, then take that feedback and learning to iterate and refine the systems and concepts.

Finally, in the back of everyone’s mind is that while DoD Directive 3000.09 prescribes what machines will be allowed to do on their own, what happens when we encounter adversaries who employ autonomous weapons that don’t have our rules of engagement?

Read the entire transcript of Maynard Holliday’s talk here and watch the video below.

If you can’t see the video click here.

Class Ten

Today’s topic was the Department of Defense and modern war.

Some of the readings for this week’s introduction to AI and modern war included: “War on Autopilot? It Will Be Harder Than the Pentagon Thinks,” “Considering Military Culture and Values When Adopting AI,” “Swarms of Mass Destruction,” “Joby Aviation raises $590 million led by Toyota to launch an electric air taxi service,” “Linking combat veterans and Valley engineers, Reveal’s drone technology wins DoD contracts, VC cash.”

We also assigned “How to Prevent a War in Asia” and “Sharpening the US Military’s Edge: Critical Steps for the Next Generation,” both written by our guest, Michèle Flournoy, who is rumored to be Joe Biden’s choice for secretary of defense.

She served as the under secretary of defense for policy from February 2009 to February 2012. She was the principal advisor to the secretary of defense in the formulation of national security and defense policy, for oversight of military plans and operations, and in National Security Council deliberations, and she led the development of the Department of Defense’s 2012 Strategic Guidance. She is cofounder and managing partner of WestExec Advisors, and was cofounder and formerly chief executive officer of the Center for a New American Security, a bipartisan national security think tank.

I’ve extracted a few of Michèle’s key insights and I urge you to read the entire transcript here and watch the video.

On China

Throughout the 1990s, we were focused on how to integrate China into the global system so that it would become a responsible stakeholder.

And we did everything we could, including WTO membership and all kinds of collaborative efforts. That worked for a while, but at a certain point, particularly under President Xi Jinping, China decided that the hide-and-bide strategy was over. It was time to take their claim, their rightful place in the international community. They became assertive in pursuing their agenda in an international forum and in particular in the Asia Pacific. And it became clear then that we have a number of areas where we really don’t see eye to eye—our interests and objectives are in conflict. Whether its economic, technological, military—there are very important competitions that we’re going to have with China over the coming years that will determine the US ability to protect its own economic vitality, but also our security and that of our allies.

That said, there are also problems when you look around the world, whether it’s the next pandemic or climate change or nonproliferation, where if the United States and China don’t figure out how to cooperate with one another we will both be in deep trouble. So there has to be a cooperative element of the relationship as well. And so that’s why I don’t like the Cold War frame. I think the name of the game is managing this competition, fostering cooperation where we can, and really focusing on deterring conflict between two nuclear powers, which by definition would be a disaster.

Is China Becoming More Confident in their Capabilities and Doubt of our Own?

They definitely are becoming more confident in their own capabilities. They’ve invested a lot in an anti-access/area denial strategy. And you see thousands and thousands of different kinds of precision munitions, rockets, and missiles. They are doing a pretty good job of trying to create a situation where it will be very costly for us to go inside the first island chain or even a second island chain. But they’re not ten feet tall; they have a lot of challenges as a military as well.

But the thing that worries me most is the narrative that’s taking hold in in Beijing about the United States, particularly in the wake of our mishandling of the pandemic, the onset of another recession, the sort of divisions and protests you see on the streets. It’s given rise to a narrative of US decline, US self-preoccupation, and the United States turning inward. And to the extent that Chinese leaders start to believe that and really believe that we have not done what is necessary to counter their A2/AD system, they could gain a sense of false confidence that might get them to take more risk-taking behavior. To push the envelope a little too far, a little too fast, and maybe cross some red lines they don’t know they’re crossing.

So it’s on us, the United States, to be very clear about our resolve, our commitment to defending our interests and allies, and how we define those. And to make really clear investments in the capabilities that will ensure our ability to project power and protect those interests in the future.

How Should the DoD Spend Smarter?

I think the real long pole in the tent is in developing new operational concepts, in light of a clear-eyed assessment of what we’re going to face from either China or, for example, Russia’s A2/AD network in Europe.

It forces us into an uncomfortable position. We like to be dominant in every domain. We like to be the one to beat. Here in every case, we’re going to have to be the asymmetric challenger. You’ve got a resident power with a huge network of capabilities. They’re going to have more quantity than us. We’re going to have to figure out how to fight it asymmetrically for our advantage.

And so that means, first and foremost, that we really do have to think about new concepts. We have to have much more competitive processes for developing those concepts. Not sort of building consensus on the lowest common denominator, concepts where everybody gets an equal share of the pie. I’m not interested in that. We have to link that to a lot of prototyping of new capabilities, experimenting with those new capabilities, and seeing how they can inform the new concepts and vice versa.

And so this is a very agile, iterative process of bringing new technologies and prototyping systems—playing them in wargames, playing them in simulations, playing them in different experiments and taking that feedback, those learnings, and then bringing it back to inform the next iteration of the design and so forth. This is the process that’s going to get us to the right place. And it’s something that’s just really, really hard for the Department of Defense to do. We’re not set up to do that quickly or well or at scale.

How Should DoD Realign its Concepts, Culture, Programs, and Budgets?

Well first, the sense of urgency you do hear at the top among the Pentagon leadership is not necessarily fully shared throughout the bureaucracy—surprise, surprise. We’ve started to adjust our acquisition approach. And the department has put out some very useful new guidance on how to approach software acquisition in a very different way than hardware acquisition. But we haven’t necessarily trained our acquisition people or incented them to have a greater risk tolerance that’s required for this agile development of emerging technologies. Nor have we created real rewards-based promotion paths for that.

And so there’s a huge human capital effort to be done here to raise the overall tech literacy of all of the folks—from the program managers to the operators. But also, to bring more tech talent into government to really help speed the transformation process. And that requires, again, some culture change. You’re not going to keep tech talent if they walk into a typical Pentagon office today. You’ve got to create a different operating culture. And I do think there’s some great examples—Kessel Run in the Air Force or the Joint AI center and parts of SOCOM. These are pockets where they’re trying a different approach, different culture, and having some success attracting the kind of tech talent the department needs. We just need to do all that at a much greater scale and with greater urgency.

Innovation versus Innovation Adoption

Thanks to organizations like DIU we’ve gotten much better at tech scouting: finding promising technologies that might have a military application and getting them on that initial contract—on a SBIR contract or an OTA prototyping contract.

But the real problem is that almost everybody hits the famous “valley of death.” So you’ve done a great prototype, you’ve won the demonstration, everybody loves you. And then they say, “Well, the next time we can actually insert you into the program and for a production contract is 2023, two and a half years from now.” And for a startup that’s like, “What do you mean? I’ve got to have access to recurring revenue to survive until then.” And so they get pressure from their investors to forget the national security side and just go commercial. It’s this terrible situation. So what do we need to fix that?

Number one, you need a more flexible set of funding authorities to bridge that gap. One idea is to allow the services to have some greater reprogramming authorities within mission areas or across portfolios, so that at the end of the year, when they have something that didn’t work, they can scrape up money there and put it into the next iteration of development for the thing that does work, and maybe get another year of bridge funding to get to that production contract.

That obviously requires some working with Congress to get them comfortable that they’ll have the transparency and oversight, but they need to give the department that kind of flexibility. I also think it involves bringing the ultimate end user into the earliest contact. So you have a program manager who’s watching this thing like a hawk from the beginning and is already thinking about how it’s going to disrupt and be integrated into something he or she is responsible for. And you have to incent that rather than just rewarding this rigorous, “we only care about cost and schedule” mindset. You’ve got to incent program managers to get better performance at lower costs, and you’ve got to be a disrupter yourself. You’ve got to bring new ideas into what you’re managing to do that, which is a very different approach. It’s not easy to do. But we have to try to figure that out.

How Can We Work More Closely with Allies and Partners?

For each of the key priority areas, whether it’s AI or robotics or quantum or hypersonics, whatever it is, we could do some mapping of which of our allies really has cutting-edge work going on, either in their research universities or in their innovation base. And look for opportunities of where we perhaps get farther faster by sharing some of that. There are all kinds of ways to do this. One is to cross invest. I know In-Q-Tel has started investing in UK and Australian companies, for example, with certain priorities in mind. I would love to see DIU get into the business of starting to bring some of those allied companies in.

I think this needs to be a topic of policy discussion of where we collectively go after some of these areas with joint ventures or joint technology development and more efforts like that at scale. It’s a very important area, particularly given that both China and Russia are going to be leveraging these technologies in ways that are really counter to our Western values in terms of surveillance systems and without respect for personal privacy and all kinds of things. And I think the more we have a common values-based approach to technology with our allies, the stronger we can be in showing up at an international forum where standards are being set or norms are being set and so forth.

What Legacy Programs Should be Downsized to Fund Investment in Emerging Technologies?

It’s a great and necessary question, because DoD always has more programs than budget. But I think with COVID and with the recession, whoever wins the White House in November, you’re going to see a flattening of the DoD budget. The assumptions of 3 to 5 percent growth over and above inflation, that’s not going to hold no matter who is in the White House. So you’re going to have to make some tough tradeoffs. I can’t give you an answer off the top my head, but I can tell you how I would think it through.

I think we need to look mission area by mission area and look across services at portfolios of capabilities to ask, “What is the mix that we need so that we have the platforms we need, but also the money to invest in and incorporate the emerging technologies that will make those legacy platforms survivable, relevant, and combat effective in the future?” And so it really has to happen on a mission area basis.

I think in some cases you may find redundant capabilities within or between services. Sometimes you’ll say, I don’t want that redundancy. I’m going to make a determination and one is going to be a winner and the other is going to be a loser. But sometimes, for the sake of resilience, for the sake of complicating adversary attack planning, you may want redundancy. You may want multiple different ways to accomplish a particular task. So this has to be done with very strong analytic grounding. Looking at both performance and capability, but also cost, and so forth.

My bias is that we have to be much more aggressive in going down the road of human-machine teaming and in gaining mass, gaining capacity, and complicating the other side’s planning process by incorporating unmanned in all domains. More unmanned undersea, on the sea, in the air, and beyond. If we can crack the code on that integration that is going to give us, for the cost of the system, a lot more capacity and capability.

What Should be Done to Enhance the Recruitment and Retention of a Technologically Superior Defense Workforce?

We’re finding one of the most important things we’re doing—who knew?—is creating a handbook for DoD folks to say, “Here are all the authorities you may not know you have for bringing tech talent in. Here are the best practices in terms of how to approach the hiring process. Here are the kinds of things you need to have in place to make those folks successful.” And give them the tools they need to really contribute. So trying to take all the learnings of where it’s been tried and failed, or where it succeeded and why. And put it in a handbook for DoD hiring authorities to say, here’s your own learnings that you can build on to get that tech talent in at greater scale and with greater speed.

One of the key barriers is still the clearance process. That seems to hold people up for a bit. But I think the department is seriously working on trying to reduce some of those barriers. Then the second piece, I would say, is career path. The services are actually sitting on a lot of STEM talent, but they don’t manage them as STEM talent. You know they forced the young captain who is the Air Force AI specialist to leave and go out and be on a squadron staff in order to check the box, so he can get his next promotion. The services need to design career paths for technologists, so that they can get rewarded, promoted, and reach leadership positions as technologists. Otherwise, we will underleverage the people who are already in the force.

What are Some Potential DoD Problems or Operational Concepts that You Would Like Our Best and Brightest Here At Stanford to Address—Now and in the Future—and Why?

I think the long pole in the tent is this notion of joint all-domain command and control in an environment that will be constantly contested. So the analogy is how do you build the equivalent of a resilient electrical grid as your command-and-control network? So that if on part of it you have an electronic warfare attack and one end of it goes down, the system automatically reroutes and is connecting shooters and sensors in a different way that allows them to keep operating without missing a beat.

So it’s coming up with how the key elements of stitching together a network of networks that has that resilience and an ability to connect and operate at the edge, even during periods where there’s disruption and you can’t call back to headquarters. To me, for future multi-domain operations this very distributed approach to warfare will be necessary.

The second piece is the technical aspects of human-machine teaming and how that really works—and again, in multiple domains, whether it’s undersea or on the sea or in the air or above. That is another key point. And then just lots of applications that can increase the accuracy and speed of our decision making faster than that of the other side. Humans still making the decisions, but getting the right information, the right analysis to them at the right moment in time, where we can make the decision and gain that advantage in the cycle of competition.

How Can the Defense Department and Our Leadership Unify the United States against These Threats in a Highly Partisan and Divided Political Environment?

It’s a great question, and it points to this question of leadership. We need a president and a commander-in-chief to step forward and provide a vision to make the case, to provide the sort of nature of the challenges, the threat assessment, why it’s important to the prosperity and security of Americans at home. And what we need to do to go after it. I would love to see a moonshot moment kind of speech, a Kennedy speech that sort of says: We’re in this competition, and this is really going to matter to our way of life. But we’re America, we know how to do this. We came out of the Great Depression. We came out of World War Two. We came out of Vietnam. And we have done this before. We are we are in crisis. We’re going to come out of this, and we’re going to be stronger and all of us need to help. So how are you going to help drive investment in the drivers of American competitiveness?

And some of it will be by doing great work in STEM in our research universities. Some of it will be investing in twenty-first-century infrastructure. Some of it will be developing these new technologies that can transform both our society and our economy and our military. But it’s about really inspiring Americans and saying, “We need your talents. We need everybody to step up and help.” That’s what I’m looking for. And, and I haven’t seen it recently, but I’m looking for that kind of leadership.

What Advice Would You Give America’s Best and Brightest, at Universities Across the Country on How They Can Serve and Make a Difference—Short of Joining the Military or Other US government Organizations?

I think we should all feel some desire, but also an obligation, to serve. I mean, to be partaking of all the incredible freedoms and benefits of this country. What can we give back? For some of us, it’s going to be going into government service or serving in the military.

But there are ways to serve in other parts of the US government. There are ways to serve in nonprofits. There are all kinds of ways to get involved in enriching society and helping to serve the United States. And so find whatever that area of passion is for you, find the time to do that. Maybe it’s going to be through your work, but maybe it’s going to be through some of the activities you do when you’re not at work. If we all stepped up to that sort of drive to serve, it doesn’t have to be in government, we’d enrich our society so greatly.

So the homework assignment is—find that passion and that path to service, whether it’s going into government for a stint, or advising or helping or investing in some other way that’s going to make your community or the country or the world a better place.

Read the entire transcript of Michèle Flournoy’s talk here and watch the video below.

If you can’t see the video click here.

Steve Blank is the father of modern entrepreneurship, an entrepreneur-turned-educator, and founder of the lean startup movement. He is an adjunct professor at Stanford and a senior fellow for entrepreneurship at Columbia University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: John F. Williams, US Navy