The Army has a disproportionate lack of African American officers in combat arms branches—infantry, armor, aviation, and field artillery. And based on its institutional inaction, the service seems to collectively believe that this is not a problem.

The hard truth is that combat arms demographics are little more than a talking point that is brought up every few years, typically by black stakeholders. The National Defense Authorization Acts of 2013 and 2020 prescribed task forces, commissions, and strategic plans. Yet, the lack of appropriate funds directed toward implementing a program aimed at change and of any fundamental policy changes makes these efforts appear to be for naught.

The lack of diversity among combat arms officers is a strategic problem, however, because under the current Army construct, only combat arms officers become senior strategic leaders—senior, three- and four-star generals that serve as the chief of staff of the Army, corps commanders, or component combatant commanders.

Solving this problem will require deliberate and comprehensive effort. But addressing two issues in particular would be especially impactful. First, more should be done to encourage African American cadets to pursue careers as combat arms officers—and to continue in those branches throughout their careers. The Army will have a role in doing so, but so will African American stakeholders at all levels, from cadets to mid-career officers. Gen. Xavier Garrett briefly discussed the phenomenon of African American cadets choosing non–combat arms career paths in a recent New York Times article covering the lack of black senior officers across the services. If the Army and the black community remain unconcerned about convincing young black cadets to branch combat arms, the status quo will remain.

Second, it is time to reconsider whether virtually the entirety of the Army’s senior-most leadership positions actually needs to be filled with officers from combat arms backgrounds.

History of Black Officers in Combat Arms

Research specific to the topic of black officers in the Army started as a broad topic covering all branches but has become more specific to combat arms as time has elapsed. As a colonel at the Army War College in 1995, retired Brig. Gen. Remo Butler wrote a Strategy Research Project, “Why Black Officers Fail,” which offered a shocking description of the inequalities of the selection of African American officers for colonel and general-officer rank. Fifteen years later, Col. Irving Smith, PhD, with updated data, showed no change in “Why Black Officers Still Fail.” Both officers identified a key problem: there is a lack of mentorship from not only black officers but also white officers who aren’t invested in a diverse force. This is why black officers still fail. Lt. Col. Okera Anyabwile provides a detailed historical examination in his recent Army War College paper, “Meritocracy or Hypocrisy: The Legacy of Institutionalized Racism in Combat-Arms.” What this history has led to is a situation in which the Army doesn’t have enough African American commanders at the battalion level to grow a number of any significance into senior leaders. And as Butler and Smith showed, this has been a fact of the institution for at least the past two generations.

Historically, African Americans who wanted to serve this country as Army officers were both limited in branch opportunities and segregated from white soldiers by the institution. The history of Fort Des Moines mass-producing 639 black officers after the United States declared war on Germany and announced its intention to join the fighting in Europe during the First World War is well documented. So is African American veterans’ inhumane treatment by the country they fought for, as expendable on the battlefield and second-class citizens upon returning home from both World Wars. African Americans who have contributed during those wars and every major conflict of this country might not view the Army as a place of belonging, and those who continue to serve might reasonably question the extent to which it is a true meritocracy, as Anyabwile explained in his paper. Whether the Army is perceived as a meritocratic institution becomes especially important because of the impact on recruitment—much like the effects of glorifying rebellious Confederates by naming military bases after such traitors who fought to uphold the institution of slavery.

It is also noteworthy that writing on the topic of African Americans’ underrepresentation among combat arms officers has mainly been done by black combat arms officers at either the Command and General Staff College or the Army War College. The lack of white officers who have studied this topic is glaringly apparent.

Diversifying Combat Arms

Working deliberately to increase the number of African Americans who choose to branch combat arms is one way to increase diversity at the strategic level. Presently, the data shows that African Americans don’t want to branch combat arms. In particular, and regardless of commissioning source, African American cadets are less likely to choose combat arms unless a black combat arms officer is present in their respective programs—as is clear from the cases of some historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that have produced numerous general officers and in specific years at West Point when black field-grade combat arms officers were present in leadership positions.

The only practical approach that has been effective is to place black combat arms officers at commissioning sources to coach, teach, mentor, and influence branch choices. Spawned from a recommendation in the fall of 2016, the Army adopted the idea of assigning pre-command lieutenants and captains from combat arms branches to HBCUs to cultivate an interest in said branches. The drawback, though, is that these selected officers are missing crucial time before competing to be company-level commanders and communicates an oddity in their files before the promotion boards. At a minimum, it is important that the Army’s Talent Management Task Force takes steps to alleviate this issue so the Army can make assignments at commissioning sources more reliable indicators of promotion potential.

The combat arms branches themselves are also a critical part of this work. The commandants of the armor, field artillery and infantry branches all have engagement officers who manage outreach to commissioning sources around the country. Many commandants have yet to identify black officers as the face of their outreach. From 2015 to 2018, only one of the combat arms branches (field artillery) had an officer who wasn’t white as its engagement officer. If the traveling roadshow of branches at schools, especially HBCUs, across the country throughout the academic year and during cadets’ summer military training is composed largely of white officers, cadets of color can’t see themselves in these units. Linking these existing efforts with the Army Enterprise Marketing element would be an important step. Currently, officers chosen for the most public-facing jobs of the combat arms branches have not yet achieved command. These officers are thrust into a high-impact position with little to no training on marketing or human capital management. Filling these positions with post-command captains and tying them to a requirement to earn a graduate degree will better equip the officers, better serve combat arms branches, and enable cadets to engage with more experienced officers when making their branch decisions.

Diversifying the Ranks of Senior Leaders

A second way to begin increasing diversity among the Army’s senior leaders is to address the way those leaders are selected.

In the case of corps and component combatant commanders, it is entirely understandable why the Army still chooses combat arms officers to fill these positions. But for the chief of staff, who no longer has operational control of soldiers on the battlefield, the Army may be adhering to an outdated practice. If the chief of staff of the Army is the principal advisor to the secretary of the Army and the green-suited strategic leader of the institutional Army, why must a combat arms officer hold this position? Truly opening up this position to all general officers regardless of their previous career fields, significantly increasing the number of all minority prospects, expands the pool from which the service’s highest-ranking strategic leader is selected. This is especially relevant today, as the Army’s Talent Management Task Force seeks to grow and promote the best strategic leaders.

There hasn’t been an Army chief of staff that wasn’t a combat arms officer for more than fifty years. In search of strategic leaders, the Army should look beyond combat arms branches and consider the totality of talent across the force. Currently, the Army counts 378 general officers in its ranks, 141 of whom were commissioned as combat arms officers. What does this mean that for the remaining 237 general officers that have promoted at every level and have led agencies responsible for billions of dollars and vital to the national security of the country, gaining experiences that would be extraordinarily relevant in the role of chief of staff? The chief of staff no longer fights the nation’s wars—and is not even in the chain of command, as explicitly codified in the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986. Combatant commanders coordinate the fight. If the Army requires its senior leaders to maintain the trust of the American people, consistently and disproportionately selecting white combat arms officers as stewards of that trust signals to the public a message of exclusivity that is not consistent with a diverse force.

What Kind of Strategic Leaders Does the Army Really Need?

The Army does not need either generalists or specialists in its strategic leadership positions, but rather hybrid leaders. A hybrid leader is the person who can be dropped into any team and can still create value for the organization. Being operationally focused and technically savvy is good, but it’s not enough; the Army requires people to think strategically and understand how they fit into the larger construct. The current career-development model ensures technical, tactical, and operational knowledge, but insufficient enterprise expertise. One assignment at headquarters doesn’t make you strategic. What the Army should be seeking to develop are “T-shaped leaders”—leaders who, through multiple broadening experiences, have added a wide breadth of experience to the depth of specialized expertise they have developed throughout their careers.

The Army creates leaders at scale through broadening assignments; not all assignments are created equal. The Army needs technical, tactical, and operational expertise, and one assignment is not enough to cultivate it. To operate at the strategic level, an officer requires exposure gained through multiple and varied assignments—from serving as an aide-de-camp or in a congressional fellowship program to opportunities outside of the service, such as the Training With Industry or Advanced Civil Schooling programs. Former Chief of Staff Gen. Raymond Odierno was pointed in his view on the necessity of developing military leaders who are competent in the political environment of national security and the Joint Staff, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and combatant commands. If the Army isn’t sending its leaders to broadening assignments early in their careers they will continue to lose the “Pentagon wars.”

In short, the Army needs to ask itself some direct questions: How many T-shaped leaders are necessary for the organization? What skills should these T-shaped leaders have? What experiences do they need to develop the T-shape that we want?

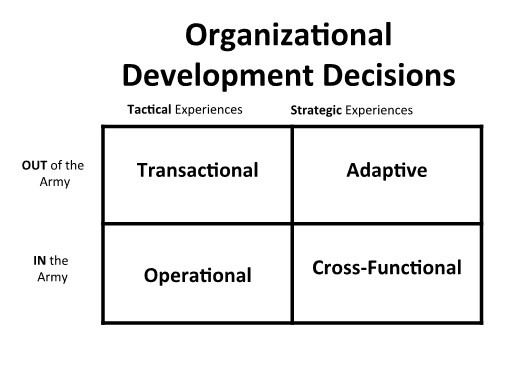

The figure below provides a way to categorize leaders’ developmental experiences.

The Army’s current mental model is self-constraining. Too strongly emphasizing combat arms (i.e., operational) experience diminishes the chances of selecting strategic leaders whose experience has made them especially adaptive—something a previous chief of staff argued that the Army needed over a half-decade ago.

This is where we return to the subject at hand. With a systems thinking approach, the Army would unpack the population and observe a more significant number of black officers in other branches and develop them to lead at the enterprise’s strategic level.

Ask Army officers what is generally held as the marker of a successful career, and most will say promotion to lieutenant colonel. Those selected for this rank and for battalion command become the pool from which brigade commanders, and subsequently general officers and division commanders, are selected. But have we been selecting battalion commanders in the best way? Arguably, no.

That’s why, earlier this year, the Army Talent Management Task Force introduced the Battalion Commander Assessment Program (BCAP). Previously, the Army was choosing battalion commanders—a major factor in promotion to colonel—with minimal information. BCAP provides more data points for better selections and represents an acknowledgement that the process could be improved, as the pool represents the “seed corn of the Army.” Yet there was one effect it didn’t have: enhancing diversity at the battalion command level.

Research shows that diverse teams are the most effective teams. A service that has a lack of diverse leaders is more likely to have blind spots. So, is the system that we have to pick battalion and brigade commanders fit for today’s fight? Or could it be improved further, in the same spirit BCAP was designed to improve it?

Diversity in a VUCA World

In a global operating environment that is hallmarked by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, the Army will require innovative thinking to overcome the challenges it faces. That means it needs diverse teams.

Achieving that diversity will require real change, not circulating memoranda, conducting studies, or holding panel discussions. We have offered two ways to begin: increasing diversity among combat arms officers and rethinking the way strategic leaders are developed and selected. Until the Army believes that increasing diversity will increase lethality, the future will remain the same: a diverse force led by white combat arms officers. If we open our aperture to think broadly and honestly about strategic leadership, the Army will give black officers, and others, a fighting chance.

Col. Hise O. Gibson is currently an Academy Professor of Systems Engineering at the US Military Academy. His prior positions include Battalion Command of 3-82 GSAB, 82CAB, 82ABN, and S3/XO for 5-158 GSAB, 12CAB. He was commissioned as an aviation officer upon graduation from the US Military Academy and holds a Master of Science in Operations Research from the Naval Postgraduate School, Master of Operational Arts and Sciences from the Air Command and Staff College, and a doctorate in Technology and Operations Management from Harvard Business School.

Daniel E. White is currently a fellow at the Department of Defense. His prior positions include political-military affairs analyst at US Southern Command, Engagement Officer for the 52nd Field Artillery Commandant, Fire Support Officer and Fire Direction Officer in 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division. He was commissioned as a field artillery officer upon graduation from the US Military Academy and holds a Master of Public Administration in International Security Policy from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Catrina Dubiansky, U.S. Army Cadet Command Public Affairs