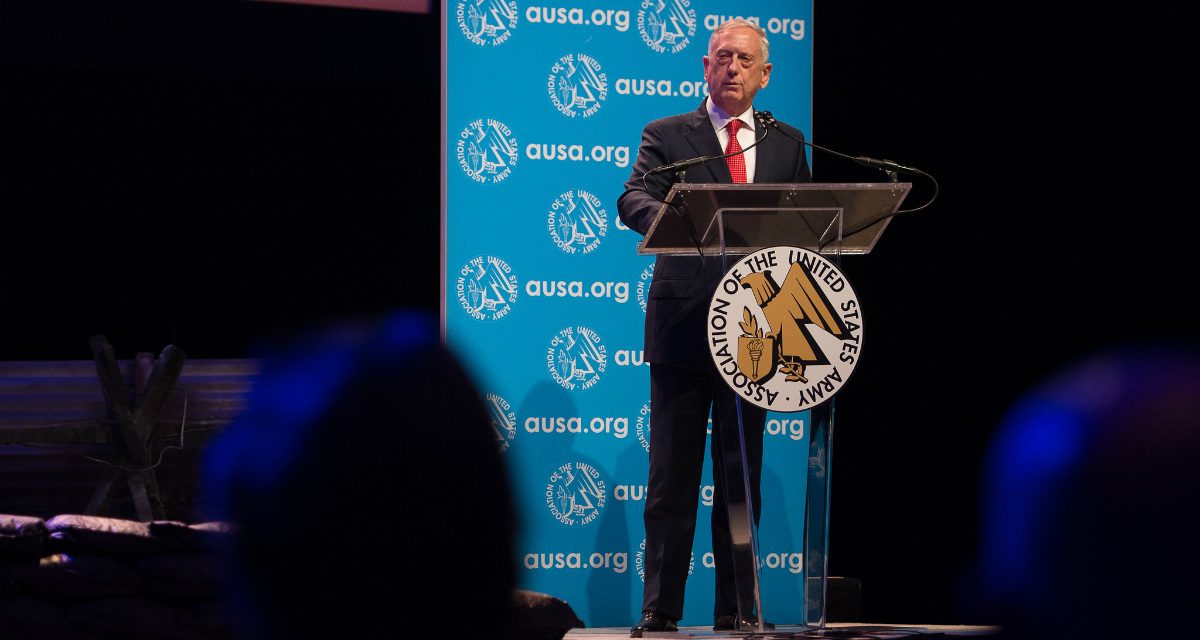

Secretary of Defense James Mattis kicked off the Association of the United States Army’s (AUSA) Annual Meeting in Washington, DC on Monday. The meeting is billed as the “largest landpower exposition and professional development forum in North America” and is attended by much of the Army’s civilian and military leadership, as well as defense industry leaders. Much of the coverage of his speech focused on what he said about North Korea. But in his prepared remarks, he deliberately touched on several threats that give a sense of his view of the world from the Pentagon’s E-ring.

Secretary Mattis was asked by an interviewer earlier this year what keeps him up at night, to which he famously retorted, “Nothing. I keep other people awake at night.” But in his speech at AUSA, he described the current international situation as “the most complex and demanding that I have seen in all my years of service.” If there are global threats that at least occupy his mind during waking hours, these are them.

The Middle East

The first two threats Mattis highlighted emanate from the Middle East. “In the Mideast, terrorists continue to conduct murder and mayhem despite significant and accelerating losses,” he said. “One state sponsor of terror in the Mideast cannot hide behind its nation-state status while, in effect, it is actually a destabilizing revolutionary regime.”

That the threat of terrorism—whether in the form of attacks against the homeland or as a destabilizing force across the broader Middle East—ranks among the top threats the secretary would identify is little surprise. It has featured on most such lists of top threats from senior defense officials since 9/11.

While he didn’t name names, it’s clear that Mattis had Iran in mind when he mentioned “one state sponsor of terror.” A fixation for several years as US policymakers grappled with the threat of an Iranian nuclear program, conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action two years ago lessened the priority given to the Iran threat, if only by a few degrees. Mattis’s decision to single out the regime could in part be read as a function of the Trump administration’s intent to decertify the nuclear deal. But equally, Iran’s reemergence as a top threat might better be understood in the context of Syria, where Iranian support to militant groups raises the specter of further destabilizing actions by Iranian proxies in the region. Indeed, the context of Mattis’s comments suggest Iran’s status as a terrorism sponsor is at least as heavily emphasized in DoD planning as its nuclear program.

Russia

Likewise, Mattis directly criticized Russian aggression in its near abroad. “In Europe for the first time since World War II,” he said, “we’ve seen national borders changed by the force of arms as one country proved willing to ignore international law to exercise a veto authority over its neighbors’ rights to make decisions in the economic, diplomatic, and security domain.”

Uncertainty over the US strategy vis-à-vis Russia has been among the biggest open geopolitical questions of the past year, and observers have noted divergence in various administration figures’ approaches. Put Mattis in the traditionalist camp, as it were. His observation of the historical seriousness of Russia’s actions in Ukraine—combined with his reassurance about the United States’ commitment to NATO and an enduring forward presence in Europe—paint a clear picture of a strategic view of Russia as a threat to European security and a shared burden that the United States and its allies must counter with vigilance.

North Korea

Comments Mattis made in response to a question after his prepared remarks received the most public attention. The secretary was asked what the US military can do to lessen the likelihood of conflict on the Korean peninsula. He responded:

It is, right now, a diplomatically led, economic sanctions–buttressed effort to try to turn North Korea off this path. Now what does the future hold? Neither you nor I can say. So there’s one thing the US Army can do. And that is, you’ve got to be ready to ensure that we have military options that our president can employ, if needed. We currently are in a diplomatically led effort. And how many times have you seen the UN Security Council vote unanimously, now twice in a row, to impose stronger sanctions on North Korea? . . . The international community has spoken, but that means the US Army must stand ready.

There’s a lot to unpack in that statement. First, it’s certainly no mistake that he prefaced his response by stating unequivocally that, currently, diplomatic and economic instruments of power are being brought to bear against the regime of Kim Jong-un, and even reiterated the diplomatic main effort later in his answer. This reinforces reporting that Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson share their strategic approach to the recalcitrant regime. But he also spoke to the role of the military instrument. In effect, he said, the military’s role is to be ready, suggesting that force may ultimately be necessary—something squarely in line with, if more subtle than, President Trump’s recent “calm before the storm” remarks. Equally, however, Mattis implied (without reading too deeply between the lines) that the military’s importance lies in part in the strength it lends to diplomatic initiatives to reduce North Korean provocations.

Nonetheless, Mattis is clear-eyed about what any fight in Korea would entail. He has said publicly that a potential conflict with North Korea “would be catastrophic.” But aside from the dangers posed by nuclear weapons, he quoted historian T.R. Fehrenbach to describe the hard fighting war would require. In his book This Kind of War: The Classic Military History of the Korean War, Fehrenbach wrote: “You may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, pulverize it and wipe it clean of life—but if you desire to defend it, protect it and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman legions did, by putting your young men in the mud.” Fehrenbach’s book, Mattis said, offers “a reminder of war’s primitive, atavistic, and unrelenting nature.” In the secretary’s mind, the image of the United States at war on the Korean peninsula, it can be safely judged, is one of difficult combat by ground forces.

The Way Ahead: Three Lines of Effort

Mattis cautioned against the Department of Defense being “dominant” and “at the same time, irrelevant.” To avoid such an outcome, he described a threefold problem statement facing the department. The US military, he said, must (1) “maintain a safe and effective nuclear deterrent,” (2) “maintain a decisive conventional force”—including “a space and cyberspace capability,” and (3) “maintain an irregular capability so we can fight across the spectrum of conflict.”

The department under Mattis’s leadership has three lines of effort to address these issues.

LOE 1: Ensure defense expenditures are sufficient to guarantee military effectiveness.

Everything we do must contribute to the increased lethality of our military. We must never lose sight of the fact that we have no God-given right to victory on the battlefield. . . . Even as our competitive edge over our foes and adversaries decreases due to budgetary confusion in this town and the budget caps, I am among the majority in this country that believes our nation can afford survival, and I want the Congress back in the driver’s seat of budget decisions, not in the spectator’s seat of automatic cuts.

LOE 2: Build and shore up alliances to bolster US military power.

We are following the example of the greatest generation coming home from the tragedy of World War II and who looked around and they said, “What a crummy world. But we’re part of it, whether or not we like it, and we’re going to do something about it.” And in that spirit they built alliances and partnerships. In the same spirit today, we’re strengthening alliances and building new partnerships, whether it be NATO, the counter-ISIS coalition, the thirty-nine nations standing together in Afghanistan, and expanding friend and partner bonds in the Indo-Pacific region. Secretary of State Tillerson’s “defeat ISIS” coalition is only one example of what this looks like in practice. Sixty-nine nations, banded together, plus four international organizations—the Arab League and NATO, the European Union and Interpol—all working in concert to defeat ISIS. But we also stand with our traditional allies as well as building new coalitions as we work together to defend our values. . . . And I will just tell you, from NATO in Europe to the Pacific, the message to our allies is we are with you.

LOE 3: Be responsible stewards of taxpayer dollars.

Rework our business practices to gain full benefit from every dollar spent on defense. We are taking aggressive action to reform the way we do business and to gain and to hold the trust of the Congress and the American people that we are responsible stewards of the money allocated to us, and that it translates directly, every dollar, into the defense of our country and what we stand for.

Mattis’s prepared remarks at AUSA lasted only about twenty minutes, and his Q&A just another ten. For a deeper understanding of his strategic outlook, he recommends reading, in addition to Fehrenbach’s This Kind of War, Colin Gray’s The Future of Strategy and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley’s own remarks from last year’s AUSA Annual Meeting. But as a snapshot of the world as he sees it, his comments offer a sobering assessment of the challenges that the world holds and of the requirements those challenges place on the US military as it prepares to meet them.

Col. Liam Collins is the Director of the Modern War Institute (MWI) at West Point. John Amble is MWI’s Editorial Director. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US government.

Image credit: Sgt. Amber I. Smith, US Army