It was bitterly cold. Soldiers huddled together wearing heavy winter jackets and black, Army-issued beanies underneath their helmets. The engines of Humvees and trucks hummed collectively, a cacophony of noise that drowned out conversations. The battalion convoy was ready to step off from Germany for a NATO exercise in Latvia. My battalion commander approached as I hopped into my Humvee. Somewhat jokingly, over the din of running engines and soldiers preparing to move out, he asked, “Which day do you think it is going to happen? I think Friday.” I responded, “My bet is on Wednesday, sir.” The date was February 13, 2022.

Both of our guesses missed the mark, but not by much. The following week, on Thursday, Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, kicking off the war that has raged for nearly two years.

During the six-day convoy I read a book that I had started in December 2021 as the Russian military buildup along the border with Ukraine continued. Titled Appeasing Hitler, the historical work by Tim Bouverie provides insight into the rationale behind the British policy of appeasement in the period leading up to World War II. It also serves as a cautionary tale of the appeasement strategy’s failure. A policy premised on acquiescing to a tyrant’s demands in the hopes of avoiding war accomplished the opposite. Instead, appeasement served to increase Hitler’s appetite for conquest and contributed to the eruption of the most destructive conflict in human history.

There have been many comparisons between Russian President Vladimir Putin’s words and those of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Both asserted the importance of reclaiming historical lands, protecting their respective countries’ ethnic populations living in the near abroad, and the fact that their aggressive actions were defensive—that they were the victims instead of the aggressors. And although it is understandable why many compare Putin’s invasion of Ukraine to the actions of Adolf Hitler in the lead up to World War II, Bouverie’s Appeasing Hitler provides an opportunity for a different comparison, to a much lesser-known war.

The Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935 is an obscure conflict, overshadowed by the world war that would shortly follow. However, the parallels between Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are striking. Historical comparisons are inherently imperfect. We cannot replicate the political, economic, social, and technological conditions that existed in the past. However, we can extract and examine themes and notable decisions in history to provide the foundation for important lessons for today’s leaders. A reexamination of the Italian conquest provides such lessons that underscore mistakes to avoid and the possible consequences the West faces if support for Ukraine falters.

First, however, a basic understanding of Italy’s imperial war is necessary. Before Mussolini and Hitler officially formed an alliance, Italy actually worked alongside Britain and France in the early 1930s. Mussolini’s Italy even joined the Stresa Front in April 1935 alongside Britain and France to counter Nazi Germany’s Versailles Treaty violations. But despite pledging to maintain peace in Europe, Mussolini had other intentions in Africa. Disregarding warnings of an Italian offensive in late 1934 and early 1935, the British government refused to confront Mussolini. Britain viewed Nazi Germany as the threat of the future and believed Italy was a crucial ally.

Britain and France’s refusal to deter Italian aggression threatened more than the sovereignty of Abyssinia. Following World War I, the League of Nations emerged and introduced a new age of international law. The league, which Abyssinia had joined in 1923, provided the protection of Article 16. This article stipulated that all members would join in common action against states that made war against another member.

The British political leadership, however, did not want to embroil Britain in a war with Italy. Britain, they argued, had no vital interests at stake. Thus, convinced neither France nor Britain would intervene, Mussolini launched the invasion of Abyssinia in October 1935.

In November 1935, France and Britain sought a negotiated end to the conflict that would have ceded the majority of Abyssinian territory to Italy. News leaked of this backdoor diplomacy and league members were outraged. France and Britain’s fiasco meant the death of the credibility of the league and the abandonment of Abyssinia to its fate at the hands of a stronger power. By May 1936 Italian forces entered Addis Ababa and declared victory.

Throughout the entire Italian-Abyssinian conflict, there was one keen observer: Adolf Hitler. He watched as the authority of the League of Nations vanished before his eyes. Most importantly, he witnessed Italy use aggression to achieve political goals and face no severe consequences.

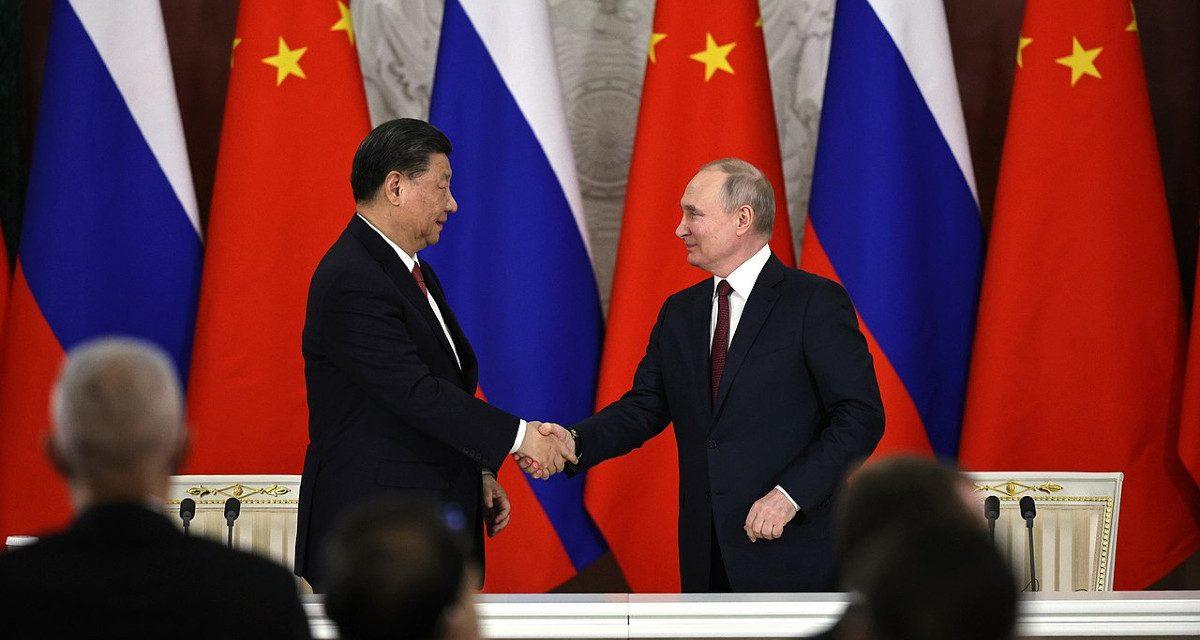

As we return to the present day, one may argue that the United States now fits Britain’s role as the declining global power. The specter of a looming global threat is no longer Germany, but China. Vladimir Putin’s Russia, challenging international norms, is Mussolini’s Italy. The state sovereignty threatened is not Abyssinia’s, but Ukraine’s. It is not the League of Nations at risk, but the pillars of the US-led post–World War II order—the United Nations, NATO, and even the international norms that have ruled since the conclusion of World War II.

We can draw numerous lessons from the Italian-Abyssinian debacle: from the necessity of major global powers abstaining from negotiating away the sovereignty of smaller states, to the importance of conventional military deterrence in complicating the political calculations of would-be aggressors, to the need for preemptive and sustained economic punishments for aggressor states in violation of international norms and laws. But there is one main lesson that is most important and applicable to our world today.

A successful deterrence now may prevent the next aggressor. Hitler watched gleefully as the League of Nations self-imploded. Mussolini’s success in Abyssinia emboldened Hitler along his path toward European domination. The primary modern comparison that comes to mind is the threat of China and President Xi Jinping deciding to employ military force to reclaim dominion over Taiwan. By understanding the dynamics in play in 1935, it becomes clear that if the United States and other members of the international community want to deter aggression against the island, then it is in their collective security interest to continue to support Ukraine. But the China-Taiwan scenario is far from the only risk. Other potential aggressors, such as Iran and North Korea, are also watching to see whether Ukraine’s international supporters will remain steadfast over the long term.

Turning specifically to the United States, the debate continues in Washington with respect to passing a new aid package for Ukraine. There are legitimate reservations within Congress on passing this funding. Concern over the accountability of aid provided to Ukraine is reasonable and the desire to have an end-game strategy for the conflict is understandable. But the fear that continued aid to Ukraine will only increase the likelihood of direct conflict between NATO and Russia misses the mark. It is the absence of continued aid, which would precipitate a weakened Ukraine and potential collapse that enables a larger Russian victory, that raises the risk of a NATO-Russia, US-China, or other large-scale war. The only lesson Vladimir Putin and other potential aggressors will learn from an end to US aid to Ukraine and a complete Russian victory in Ukraine is that aggression works and that authoritarian systems can outlast the West.

Britain declared it had no vital interests at stake in Abyssinia. Some argue the same with respect to US interests in Ukraine today. But maintaining support for Ukraine through the continuation of military and economic aid may not only guarantee a more just peace in Ukraine; it may also help prevent the next, larger war from occurring.

First Lieutenant Dean D. LaGattuta is a 2020 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, majoring in political science and minoring in Eurasian studies. He serves as a military intelligence officer in the United States Army.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: kremlin.ru, via Wikimedia Commons