Recent US administrations have been criticized for lacking a coherent approach toward Latin America and the Caribbean. Despite some efforts to deepen its ties to the region, US leaders have demanded the region address the rise of China, immigration, and other issues. This approach makes it appear as though the United States is only concerned with hemispheric affairs when it is directly impacted. To obtain its own objectives, the United States needs to build trust with the region—something that others have noted will take time given the complicated history of the relationship. One way to do this is by shifting the conversation across government—including from the US military and US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) in particular. How SOUTHCOM articulates its policy through its annual posture statements—official documents that provide insight into what the command (and by extension the US government) sees as the most pressing security challenges and opportunities—is important in shaping the relationship.

Of course, we should look not just at what SOUTHCOM says, but at where it spends its budget and the actions that it takes. However, seeing how the SOUTHCOM commanders have framed the challenges facing the region and opportunities for collaboration provides valuable insight into how the command approaches the region. A key aspect of posture statements—one that is vitally important to consider when analyzing their contents—is that they are a product of a political process. Budget considerations weigh heavily on the authors and commanders, particularly as members of Congress expect these documents to align with anticipated spending and congressional interests. They also provide a window for leaders across the region on how the US government views the strategic landscape. While US military engagement is not a precise reflection of US foreign policy engagement as a whole, there are states in the region—including Brazil and Colombia—whose militaries play a critical role in diplomacy, making it an especially important dynamic to examine.

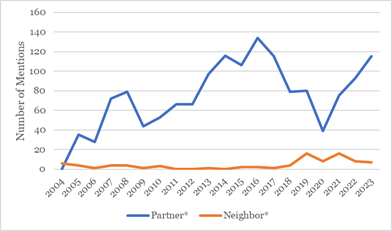

SOUTHCOM posture statements can thus give some indication of how the United States views countries in the region. Does the United States see them as potential allies or challengers? Are there opportunities for partnership? While three countries in the region—Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia—have the status of major non-NATO ally, SOUTHCOM’s posture statements have been inconsistent in defining the region as potential partners. Admiral James Stavridis (SOUTHCOM commander, 2006–2009) was one of the first to push the idea that SOUTHCOM does not need to lead initiatives in the region, but instead support security assistance programs, human rights education, and humanitarian aid. By leveraging national security to support diplomatic and humanitarian initiatives, the United States could build partnerships and develop goodwill between countries. The posture statements under his command clearly demonstrate this policy shift, with the word “partner” jumping from twenty-eight appearances in 2006 to seventy-two in 2007.

The emphasis on partnership would ebb and flow in patterns that largely correspond to presidential administrations. The increase in the use of the term “partner” (or variations of it) that was seen in 2007 continued through the two terms of Barack Obama’s presidency. Over the course of Donald Trump’s administration, SOUTHCOM turned away from referring to the region’s countries as partners. Under President Joe Biden, there has once again been a marked uptick. While there has been a resurgence in recent years, continuing to find spaces for cooperation and partnership—both in action and rhetoric—is critical for addressing the transnational challenges facing the region. Framing Latin American and Caribbean states as potential partners can help create the space for SOUTHCOM to seek out strategic allies rather than creating an opening for other countries to gain a foothold.

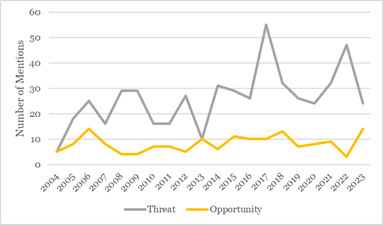

The flip side of this is when the region itself is framed as a threat. While the Department of Defense typically takes a threat-based approach in identifying where it should engage, it may do so at the expense of missed opportunities. When looking at SOUTHCOM’s posture statements, there is a clear pattern in which threats are emphasized dramatically more than opportunities. While the identification of potential threats is naturally a core part of defense thinking, it is important to recognize how these documents may be perceived from the outside. Who and what the United States perceives as threats have shifted in recent years. The 2017 posture statement used “threat” more than any other posture statement in the last twenty years, with a heavy focus on how to address “threat networks” mostly from the region and nonstate actors. With an emphasis on drug trafficking, criminal organizations, and other illicit activities, the rhetoric suggested that the largest threat in Latin America was coming from the region itself. However, the 2022 and 2023 posture statements shifted the focus from regional “threat networks” to malign actors outside the Western Hemisphere. While the identification of threats and problems emerging from the Western Hemisphere is important, it is equally—if not more—important that SOUTHCOM not miss identifying opportunities to collaborate with partner nations as it provides space to engage with the region in a more positive light. Fortunately, this year’s posture statement saw a shift in the identification of threats toward one that looked more at opportunities.

Shifting the threat-based framing requires recognizing that not all countries view the same actors or situations as threats. One area where this is true is the perception of the role of extra-hemispheric actors within the Americas—particularly as it relates to China. Over the past several years, SOUTHCOM’s posture statements have seen a rapid increase in mentions of China. While this is reflective of US concerns over Chinese presence in the region, it is important to note that countries in the region have viewed China not as a threat, but as an important shift in the geopolitical landscape that provides opportunities. Indeed, China became a major source of financing and aid to the region in the twenty-first century. This poses a challenge for the United States—if it condemns the role of China in the region and views it as a threat, but does not take active measures to serve as an attractive alternative to China, then those condemnations fall on deaf ears. While the preoccupation with China and Russia within the 2023 posture statement remains evident, continuing to seek opportunities to engage with partners in the region was at the forefront of discussions on this issue.

In the same vein as shifting from viewing the region as a source of threats to one of partnerships, it is possible to shift the threats-based approach in posture statements toward one that emphasizes security opportunities. This can be done in a variety of ways across different issue areas. For instance, there are various areas where the United States, through its military-to-military relations, has strong comparative advantages and offers opportunities for addressing challenges. Collaboration in disaster response and addressing impacts of climate change presents opportunities to address these challenges more effectively. As the United States seeks to address the root causes of migration and crime in Central America, looking at opportunities for the US military to engage with partner states rather than just viewing immigration as a threat can foster greater support for these initiatives. Finally, several Latin American countries have a long history of supporting UN peacekeeping operations. This could provide an opportunity for the United States to engage with partner nations to enhance their capabilities and reduce the burden on the United States to engage in these areas. In enhancing capabilities, SOUTHCOM continues deepening its relationships with militaries in the region.

In doing so, SOUTHCOM should be careful to ensure that these engagements strengthen human rights commitments on the part of foreign militaries and do not commit atrocities. Working to collaborate with militaries in the region to ensure that they are committed to human rights and democracy is particularly important today. With democracy facing threats in the region and across the world, shoring up the role of militaries to preserve democratic civilian rule is important and an area where the United States has long engaged with the region. Ensuring that militaries in the region refuse orders that violate human rights or weaken democracy in their country is paramount.

While many of these opportunities are about addressing specific threats, shifting the emphasis from a threats-based approach toward seeking collective opportunities may provide useful paths forward. Relationships built more on cooperative planning could more efficiently help determine which threats can be turned into strategic opportunities, and they could also highlight that regional partnerships are an asset that of genuine interest to the United States rather than just a necessary means to an end.

SOUTHCOM and the Department of Defense are in a unique position to support US foreign policy in Latin America and the Caribbean. As SOUTHCOM commander General Laura Richardson and her staff prepare the command’s 2024 posture statement, the command should double down on the 2023 posture statement and seek to frame its posture to take advantage of these opportunities and deepen its partnerships in the region. If this approach is to work, however, it needs to be shared with other elements of the government and its words need to be matched with action.

Adam Ratzlaff is a specialist and consultant in inter-American affairs as well as a PhD candidate in international relations at Florida International University. He has previously worked with the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and Global Americans, among other groups.

Emma Woods is the chair of the Young Professionals in Foreign Policy’s Latin America discussion group. She holds a BA from the University of Virginia in Spanish and global studies.

Jeffery A. Tobin is a political science doctoral candidate in the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University. He was a journalist for more than twenty years.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. 1st Class R.J. Lannom Jr., US Army