At 8:50 pm on August 6, 1990, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a deployment order. It was the first formal move in what would three days later be officially named Operation Desert Shield. The United States Army’s mobilization and deployment of the equivalent of three corps-sized units for the operation was a phenomenal logistical achievement. Like its sister services, the Army overcame significant planning and operational challenges move manpower, weapons, vehicles, and the other materiel necessary to respond to Iraq’s invasion and annexation of Kuwait. Despite the passage of twenty-five years, the scope of the Desert Shield deployment offers lessons for today’s Army in the event of large-scale combat operations across its components—COMPO 1 (active Army), COMPO 2 (Army National Guard) and COMPO 3 (Army Reserve).

The Desert Storm Buildup

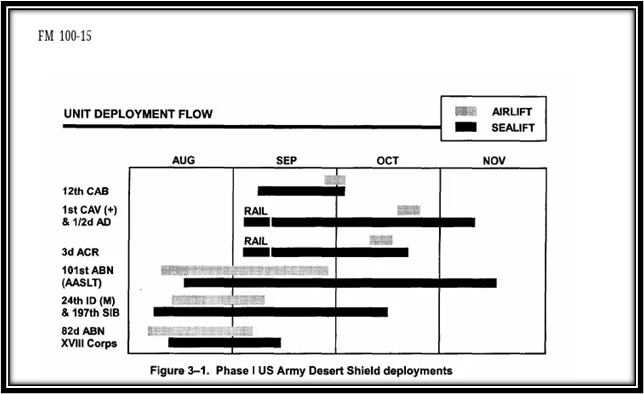

Due to the nature of the immediate threat of an Iraqi assault into Saudi Arabia following the occupation of Kuwait, the 82nd Airborne Division’s ready brigade was the first Army unit to land in country and was on the ground within thirty-one hours of alert (which included flight time). The brigade’s immediate mission was to secure airfields outside of Dammam for follow-on ground and US Air Force units. Simultaneously, Air Force aircraft were flying into theater and would have been vulnerable on the ground if an Iraqi air or missile attack had occurred. This necessitated the deployment of the 11th Air Defense Artillery Brigade with its Patriot batteries. The following graphic depicts the deployment timeframe for XVIII Airborne Corps units.

As this graphic illustrates, the majority of deploying soldiers were airlifted into theater via either military or commercial airlift. Unit equipment was primarily shipped via sealift. Of note, the 1st Cavalry Division and the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment initially moved their equipment via rail from their home station at Fort Cavazos (then Fort Hood), Texas to ports for sealift movement, followed by the movement of the units’ soldiers via airlift.

A report on the logistics of the buildup for Operation Desert Shield noted the magnitude of the undertaking:

The amount of Army equipment and supplies shipped to Saudi Arabia in six months totaled 2,280,000 tons, most of it by sealift. In a similar period 1,622,000 tons were shipped to Korea and 1,376,000 tons were shipped to Vietnam.

Over 15,400 flights were flown by military and civil aircraft under control of the Military Airlift Command throughout Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm deployments. The flights carried more than 484,000 passengers and more than 524,000 tons of cargo.

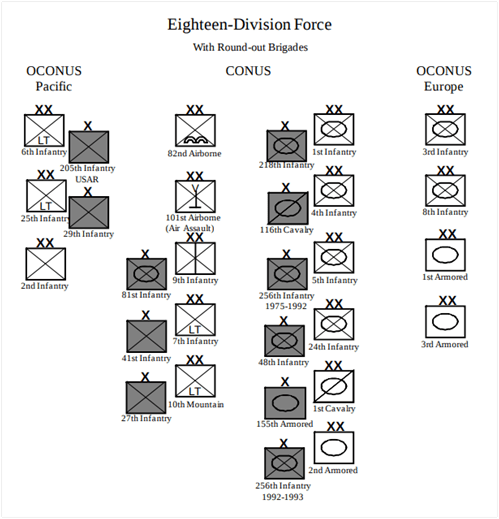

In 1990, the Army was structured under what was the called the Total Army concept. Active duty divisions would optimally consist of two active duty brigades and one Army Reserve or National Guard brigade. The idea was to pair up units and permit them to train together and, if needed, fight together.

On paper and in theory, this looked impressive. However, in practice and considering after-action reports, including congressional hearings, the structure had significant shortcomings.

There was initial (and to a degree, ongoing) controversy regarding the call-ups of three National Guard roundout brigades to support their assigned divisions. The 1st Cavalry Division’s roundout brigade was the 155th Armored Brigade (Mississippi Army National Guard). The 5th Mechanized Infantry Division was assigned the 256th Infantry Brigade (Louisiana Army National Guard). The 24th Infantry Division had the 48th Infantry Brigade (Georgia Army National Guard). In the end none of the three National Guard roundout brigades would deploy to the Middle East.

The rationale for not deploying these units was that President George H. W. Bush had only ordered a partial mobilization and that there were adequate active duty brigades available for deployment into theater. However, Army leaders at the time were apparently concerned about deficient leadership and training, maintenance, and individual soldier deployability. These concerns were amplified following a public relations disaster in which dozens of soldiers of the 256th Infantry Brigade went AWOL and complained about their poor deployment training conditions. Information that became available after the fact validated these concerns. In an evaluation of the three roundout brigades’ role during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, an Army officer put it succinctly: “Unit readiness, unrealistic requirements, and time all played their part in stopping the brigades from deploying.”

While the roundout brigade concept was not employed, the need for support and sustainment units from the Reserve and National Guard was critical.

During Operation Desert Shield, 297 National Guard units made up of 37,484 soldiers deployed to Southwest Asia with an additional 84 units and 10,132 soldiers deployed in the United States or in Europe or awaiting deployment orders.

Most of the National Guard units that deployed into theater were combat support and combat service support. These units filled multiple gaps within COMPO 1, notably transportation, military police, and intelligence functions. Anecdotal information indicates that these Guardsmen were better prepared to deploy because in some cases, their civilian occupation mirrored their military occupational specialties.

COMPO 1 military intelligence units, especially in the XVIII Airborne Corps, focused for years on potential threats and missions in Central and South America, had virtually no Arabic linguists for the all-important tasks of prisoner interrogation or communications intercepts. The same held true for VII Corps units, whose historical focus had been on the Europe and the Warsaw Pact. The shortfall was addressed with the deployment of 344 linguists from the 300th Military Intelligence Brigade of the Utah National Guard.

While there were two National Guard combat arms units (the142nd and the 196th Field Artillery Brigades) involved in Operation Desert Storm, the three mobilized roundout brigades had yet to complete the process of being validated for deployment. Only one of the three would achieve validation. Of note, nearly all of the active duty field artillery units from COMPO 1 were deployed—even from those corps that did not deploy. The others remained in the United States and Europe as reserves.

A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the efficacy of the National Guard roundout brigades compared to that of the active duty replacement brigades during Desert Shield is instructive and harsh. There were four major findings:

- “Active brigade officers and noncommissioned officers were better trained to lead.” There was a wide disparity in the percentages of junior officers (below the rank of major) who had completed their respective branch basic courses and advanced courses. While most active duty officers had completed their professional education courses, many National Guard officers had not. For example, only slightly more than 50 percent of officers in two of the roundout brigades had completed the advanced course. Noncommissioned officer professional development course completion rates were very similar: In one of the National Guard brigades, only 28 percent of noncommissioned officers had completed the Primary Leadership Development Course, while in another the figure was 51 percent.

- “Active brigade soldiers were more ready for deployment and better trained in individual job and crew skills.” There were significant manning shortages in the National Guard brigades, which had a negative impact on collective training and crew proficiency. In addition, the active brigades had significantly higher percentages of soldiers fully trained in their military occupational specialties than their Guard counterparts.

- “More collective training opportunities resulted in active brigades that were more combat ready.” Collective unit training at the platoon through battalion levels occurred more frequently for the active brigades than it did for the Guard units. Unsurprisingly this resulted in better performance by active units having undergone not just local training exercises but also rotations at combat training centers, unlike their Guard counterparts.

- “New equipment for replacement brigades did not pose difficulties,” but both active duty and National Guard brigade reported equipment shortages. Shortages of authorized equipment were present in both types of brigades. However, the GAO concluded that these shortages did not lead to an overall degradation of unit readiness. Of note, the specific shortages were related to nuclear, biological, and chemical equipment, communications equipment, and night-vision devices.

Lessons for Today

The mobilization for Operation Desert Shield was massive in its scale and its complexity, and the way it was conducted holds lessons for the Army today as it prepares for large-scale combat operations. In particular, the employment of forces across both active and reserve components—with widely varying degrees of success—is instructive across all three COMPOs.

Within COMPO 1, the challenges with the shift from brigade-centric expeditionary deployment to division and corps deployment are primarily ones of scale and scope. There is a cautionary note, though: While the Army prepares for large-scale combat operations against a near-peer pacing threat, the possibility exists that like Desert Shield, the United States is faced with a different threat in an unexpected theater.

In COMPO 2, the decision not to utilize the National Guard roundout brigades created significant morale and leadership challenges. The GAO report makes it clear that these units were not ready for deployment into a combat theater. This is far more an indictment of the condition of the National Guard at that time than of individual units—a conditions that did not lend itself toward soldier and unit readiness. Even with dramatically improved readiness, however, in the event of US involvement in large-scale combat operations, any mobilization and deployment period is going to require an extensive lead period to enable these units to prepare.

For COMPO 3, the activation, mobilization, and deployment of Army Reserve units differed from that of the National Guard. The majority of the 123,596 reservists activated and deployed were in combat support or combat service support missions. Records indicate that 25,138 mobilized reservists remained in the United States augmenting active duty forces, primarily at the airports and seaports. As of March 10, 1991, 13,170 soldiers had been recalled to active duty from the Individual Ready Reserve. As noted, those reservists whose civilian occupations were relevant to their military occupational specialties were better prepared for operations than those civilian jobs were not. This will also be the case in any future large-scale combat operations involving COMPO 3 units.

Across all three COMPOs, there is a delicate balance between readiness at both the individual and the collective level and the maintenance readiness of vehicles and equipment. Alternative means of training and exercise should be enabled, but only if it is an effective tool that enhances readiness. Distributed learning and mobile training teams can provide partial solutions. Maintenance readiness levels are an ongoing challenge across the Army, in both active and reserve components. Units may have overages of vehicles and equipment that, despite being on their property books, do not contribute to unit lethality or readiness to conduct mobilization and deployment. Disposing of excess or obsolete equipment is a course of action, but it must be done in a way that advances readiness.

Just two days after the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued its deployment order in early August 1990, the first US soldiers arrived in Saudi Arabia. Five days later, the first ship carrying Army equipment was underway. In just six months, there were more US soldiers in Saudi Arabia than there were Americans living in Newark, New Jersey or Tampa, Florida, along with nearly 2.3 million tons of materiel. In the event of a major war, the Army could be called on repeat such a feat. But seeking to do so without learning the difficult lessons from Operation Desert Shield would be a grave mistake.

Dr. Stewart W. Bentley is a military analyst at the Deployment Process Modernization Officer at CASCOM, TRADOC. He is a former infantry and military intelligence officer with a master of science in strategic intelligence from the National Intelligence University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Renee L. Sitler, US Army