We have many choices if we want to define and think about military innovation. I propose that we can think of it better by thinking of Leonardo DiCaprio.

But before I get to that very counter-intuitive and somewhat bizarre proposal, let me first briefly talk about innovation the way we do typically do. RAND, the forefather of the modern military-industrial-academic think tank, defines innovation as the “development of new warfighting concepts and/or new means of integrating technology.” According to historian Williamson Murray, successful military innovation involves a study of one’s own and others’ experiences and a willingness to continually transform in the current moment based on those relevant lessons from the past, from realistic experimentation, and the activities of those with whom you are engaged as friend or foe. The U.S. Army defines innovation as “the action or process of introducing something new, or creating new uses for existing designs.” Less militaristic, others think of innovation as the addition of idiosyncratic originality to the mastery of the conventional. Sometimes, innovation comes in the shape of an accident or serendipitous chance that results in a favorable effect that gets exploited, or as an “exaptation”—transforming or borrowing an idea or method from one domain and transplanting its utility into another—or simply, like DARPA, preventing surprise by creating it.

But, nearly all of them stand firm on the concept of “change” (unlike DiCaprio—who never seems to change or age). Doing some thing (activity 1), and then giving it up and changing to do some thing else (activity 2), presumably because doing thing 2 is better for some reason—perhaps cheaper, less deadly (i.e., less risky to one’s own), more deadly (i.e., poses a greater threat to one’s enemy), or a speedier route to the desired destination. Or, for the same reasons, doing something in some way (A), and then giving it up and changing to do the same thing in a different way (B). Or, third, changing both the activity and the manner in which that activity is conventionally done (going from activity 1A to activity 2B, for instance). As summarized by Stephen Peter Rosen, change—it goes nearly without saying—results in some “new” verb or noun: a new tactic, a new doctrine, a new task organization, or a new weapon or new way to use that weapon.

Admiral J.C. Wylie’s thinking on strategy in war, though, paints a slightly more complicated and colorful (and therefore more interesting and engaging) picture of innovation. And he did this without ever mentioning the word “innovation.” For him, change on the battlefield or the high seas, or even in the heads of the political statesman debating a war’s end-state, was about adapting to a new “pattern.” Belligerent nation A will attempt to establish some measure of “control” over enemy nation B (usually at first by controlling the actions of the enemy’s military through force or threat) so that B accepts A’s terms. If successful, A will “continue to press;” if not, and is “restrained in some way, and a sort of equilibrium sets in,” then neither side seems to have an apparent or real advantage…or fails to see that they do. The conflict settles into a “dynamic state of indecisiveness.”

What makes Admiral Wylie’s approach extremely interesting is that he then sails off to another observation point, and assesses this attempt at “control” from the perspective of the other belligerent party B, the side that was not the original “aggressor.” Initially “beset by troubles,” he wrote, the victim B is “engaged in a tooth-and-toenail scramble to salvage as much as he can from falling under control of the enemy . . . if he fails to reduce the aggressor’s initial control of the course of the war, he loses [but] if he is successful in first minimizing then neutralizing the aggressor’s control . . . then there comes into being the period of comparative equilibrium.”

According to Wylie, this state of indecisiveness, or fluttering back and forth with no real gain for either side, presents the setting—laying out the sand table, so to speak—for where the “pattern of war” might need to change. The party that changes the pattern is more likely to end the day with a victory. In other words, change involves adaptation, and adapting results in what appears to an outsider often as innovation (at various scales). Even though the Air Force apparently distinguishes between adaptation and innovation—looking at the time frames involved and the parties “responsible” for each—there is something to be said for looking at innovation in the light of belligerents adapting to each other over time. If in competition, one adapts to another’s innovation or gets beaten out of the industry or dies; sometimes, one must innovate in order to adapt. There is no obviously clear reason to parse the two so cleanly.

Let us assume for the sake of argument—and it is not a large leap to make this assumption—that combat at every scale involves some degree of what Clausewitz called “friction” or uncertainty. As with all things human, combat is almost defined by its inherent friction, and it will always be a risky investment of violence…risky because one can never forecast the enemy’s next move, the reaction of sideline observers, the effect of non-combatants in the way, the consequences of the violence one inflicts, or quite manage to deliver one hundred percent of one’s effort one hundred percent of the time. In other words, Murphy is always lurking somewhere in the terrain, attempting to de-strategize you.

If friction and uncertainty are ever-present, so is the probability that both sides (if we can reduce the combat to two opposing forces for the sake of this argument) will err, miscalculate, or misjudge the next step to take or the other side’s intentions and capabilities. It also goes without saying that this propensity to err, regardless of one’s training, resources, or good will, stains every scale of combat—from the individual rifleman to the combatant commander’s staff. No one is immune, and it these errors, miscalculations, and misjudgments add to the sum total of the friction.

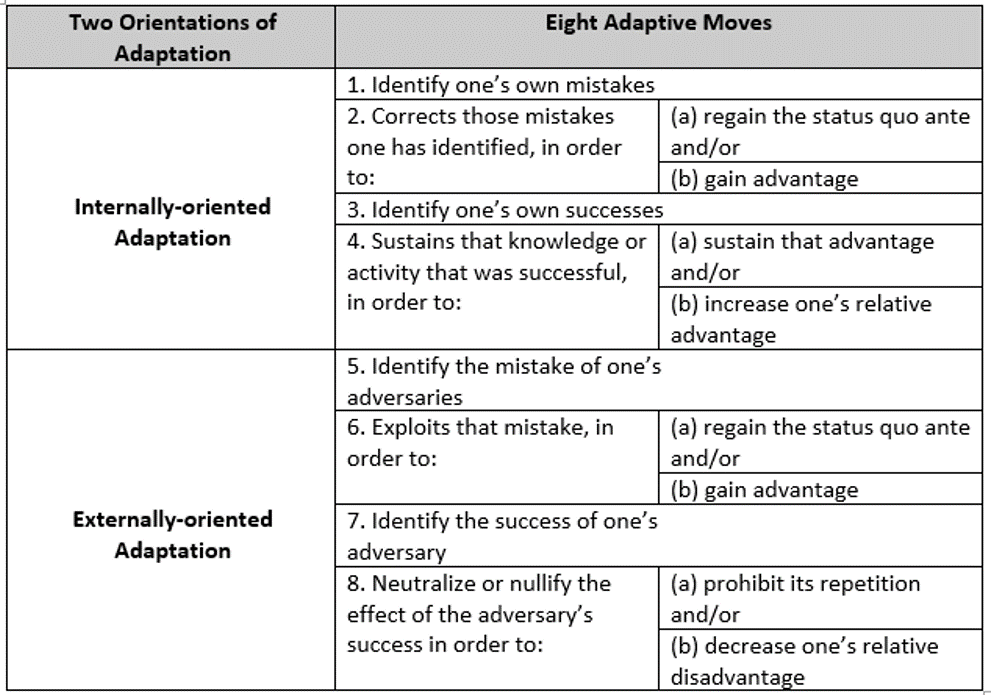

Looking at combat this way, each belligerent (again, it doesn’t really matter how many or who they are) is characterized at least in part by the extent to which they respond to error. By “extent” I mean both in speed and degree. By “respond to error” I mean that each party can in part be judged by how they wisely and effectively they make eight adaptive moves. These eight adaptive moves can be further binned into two categories: first, internally-oriented adaptation (being self-aware); second, externally-oriented adaptation (being outwardly cognizant).

Whether one internally adapts or externally adapts first, or does both simultaneously, is immaterial. What matters is that each party can be thought of as accomplishing (or failing) in either regard by the extent to which (again, in speed and degree) they make their adaptive moves relative to each other. These eight moves are broadly written; deliberately, they are vague enough to accommodate a range of possible behaviors or things to change, whether they be technological, tactical, material, or analytical. Importantly, the eight moves are meant to capture adaptation—and thereby innovation—as an interactive process of feedback loops. Imagine if John Boyd’s “O-O-D-A Loop” was really a ball of two or more loops, each representing a party to the conflict, and each loop entangled with another. It is a messy visual. But so is picturing belligerents battling it out on any scale, in any environment, over any objective.

This reciprocal adaptation—the feedback loop each party relies on as it changes both internally and externally—can be thought of as “intra-conflict innovation.” Let’s define this a bit more specifically. Given an actual or perceived adversarial condition or adversarial competitor, intra-conflict innovation is an unexpected or un-programmed adaptation by a belligerent actor that results in qualities or behaviors of that belligerent that are thought to be an improvement over the status quo ante (prior to the exposure to the adversarial condition) or results in an advantage over that belligerent’s competitor. In other words, do as Sun Tzu says: change and move like water flows, without consistent shape or direction or speed.

What does this abstraction look like on the muddy ground? Adaptive innovation gets expressed, or is manifested, by the exercise of “control”—harkening back to Admiral Wylie, but in terms used more recently by Milevski: “the potential to take and actually exercise control is the core difference between landpower and other tools, military and non-military, of grand strategy . . . [because control means] exploiting and broadening options for manipulating one’s own power for positive strategic ends.” In this way, adapting (necessarily accepting and learning from one’s inevitable blunders and those of the other, as well as the successes of each) is the means by which we maneuver—in the broadest sense of the term—into a position to achieve one’s specified goal. This conclusion calls into question the largely-accepted adage that “seeing first, deciding first, and acting first,” is the holy trinity of warfare. If the belligerent recognizes and learns from its own mistakes so that it safely returns to the status quo ante, for example, and can neutralize the identified success of the opponent in way that the success does not repeat itself, then it is insufficient for the belligerent to be merely faster to the front, with better C4ISR, and led through decentralized mission command principles. What will matter more is the extent to which that belligerent can also correctly spot its own success story, exploit it, and increase its relative advantage over the opponent while exploiting its inevitable blunders or miscalculations. In other words, being last sometimes means coming in first.

Therefore, the frequency with which the belligerents adapt, and each party’s adaptability (i.e., their capacity and capability to make those eight adaptive moves) relative to the other, can be thought of as another layer characterizing a particular combat (really, at any scale one chooses). We can describe this by labeling the belligerents’ intra-conflict innovation in one of four ways.

- Consistent adaptation over the duration of the conflict by each party—that is, they are symmetrical or balanced in their competence at adapting advantageously. This would approach Wylie’s description of that state of equilibrium that tends to leave each side without a relative benefit.

- Inconsistent adaptation over the course of the conflict, but both sides do it equally poorly when they try—that is, they are still symmetrical or balanced, and Wylie’s equilibrium cancels out each side’s tactical wins and losses.

- Inconsistent adaptation over the course of the conflict, but one side is qualitatively better at it—they engage in the eight adaptive moves faster or more comprehensively than the other side, leading to asymmetry.

- Consistent adaptation over the duration of the conflict by each party, but one side is qualitatively better at it—they engage in the eight adaptive moves faster or more comprehensively than the other side, leading to asymmetry.

If we were to be given a choice of which of these four states or postures we’d like to plop down inside, I suspect the easy answer would be number four: we would choose to be asymmetrically better at making our eight adaptive moves consistently over the duration of the conflict. Adapting consistently and better than one’s opponent suggests that you are, in effect, staying “ahead of” the opponent, or at least outside his ambit—outside of his ability to strike at you successfully. This means that the party adapting more frequently and better than the other player is dictating the rules of the game as it is being played. I suppose, to make the point differently, we can analogize it to lucid dreaming, or, with a bit more jest, call it the “Inception Theory” of war. Hence, how Leonardo DiCaprio relates to military innovation. It was a long road to get there.

Here, I pause to ask a difficult question. Does this not recalibrate our meter for measuring military “victory?” Certainly, in some cases, victory comes in the form of conquered territory, or the ability to freely maneuver one’s military forces at will, or subjugating another’s community, or all three at the same time. Sometimes though, in the long view, victory is more appropriately defined in terms of political cost, or with the objective criteria like casualties inflicted or endured. But some scholars, like J. B. Bartholomees and Emile Simpson, persuasively suggest that victory is not so mathematically or geographically straightforward. Rather, victory is in the eye of the beholder. Because war is a “continuation of political intercourse with the admixture of other means,” as Clausewitz wrote, or a social act that reflects cultural norms and expectations for controlled violence, as Keegan believed, military victory can only be accurately described and defined in political or social terms. That means military victory is a function of resolving political and social problems. Both of which, we can lament but must acknowledge, are messy, unpredictable, uncertain, cannot be easily defined, have no stock solutions acceptable to all observers, and are usually symptoms of other problems that similarly vague, unquantifiable, and unmeasurable—they are “wicked problems.”

Therefore, the perception (by a range of a varied audiences with a multitude of opinions and vested interests) of what we do or do not do with our military may matter more than what actually happens. Winning this sort of wicked game is not a function of who has more points at the end of regulation. Focusing on one’s intra-conflict innovation—how one adapts and therefore potentially manipulates the rules of the game—is one way to avoid the trap of hunting a meaningless and empty victory.

(A cautionary note to the reader: other than referencing a well-known film and actor, I have purposefully left this essay abstract; far more theoretical than empirical. In fact, I have carefully avoided throwing in any illustrative historical or contemporary examples. I did so because I did not want to unintentionally convey a normative opinion about those episodes, nor look like I was hunting for examples to prop up the propositions I’ve made. The “implied task” for the reader then is to find empirical examples that prove or disprove these points, or cut the rug from underneath my argument. Either way, my intent was to start a conversation about this subject. Sometimes starting with a controversial fact from the horrors of the real world is not the best way to do that. Here, I’ve chosen to basically start, non-confrontationally, from scratch.)