The security situation in the Sahel region is complex, daunting, and not improving. The annual number of fatalities caused by conflicts in that part of Africa is estimated to have risen by 50 percent in 2022 to about nine thousand. Fighting among violent extremist groups, clashes between them and government and foreign soldiers and mercenaries, and attacks on civilians by all sides have added to the death toll. The use of irregular warfare tactics by extremists, including improvised explosive devices, have also inflicted a growing number of casualties on United Nations peacekeepers as well.

The situation in Mali and much of the rest of the Sahel is worsening in part because the UN and democratic countries have failed to come up with a strategy to contain the conflict. As the International Crisis Group put it: “Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger show no signs of beating back stubborn Islamist insurgencies. Western leaders, whose military involvement over the past decade has done little to stem violence, seem at a loss at how to respond to coups in Burkina Faso and Mali.”

This inability to respond effectively has led to popular demonstrations against UN peacekeepers and France. It has also prompted some governments in the region to turn to Russian mercenaries like the Wagner Group to put down the insurgents and to demand that French troops leave.

Nowhere is this tragic scenario more evident than in Mali, where Western European countries and Canada have pulled out their troops. France left after trying for nearly a decade to improve the situation, spending billions of dollars, and losing over fifty of their soldiers. French President Emmanuel Macron, in announcing the withdrawal in February 2022, said, “We cannot remain militarily engaged alongside de-facto authorities whose strategy and hidden aims we do not share.”

The deep disenchantment with what had been a close relationship between a former colony and the country that had ruled it was mutual. In August 2022, the Malian foreign minister wrote a letter to the president of the UN Security Council claiming that France had provided intelligence, arms, and ammunition to terrorist groups. The letter also threatened to resort to “self-defense” if France continued such alleged operations.

The French are not the only ones for whom thing have not gone well in Mali. The UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSMA, has suffered over 290 deaths and is on track to have the most fatalities of any operation in UN history. It is also one of the most expensive with an annual budget of nearly $1.3 billion. In once recent incident on February 21, 2023, three Senegalese peacekeepers were killed by a roadside bomb, one of over five hundred such attacks on MINUSMA personnel carried out using IEDs.

The situation in Mali is not just bleak. It is hopeless. There is no military strategy that donor countries would be willing to use that would make the war winnable. If there is any positive aspect in this situation for the United States, it is that it does not really matter. The United States has no vital national interests at stake in Mali. That won’t prevent the US government from continuing to pursue a strategy that will not only fail but make matters worse. Understanding why this is the case requires reviewing how American policy got to where it is today.

The Origins of a Failed Strategy

During the Cold War there was a tendency to support any leader who professed to be anticommunist. That was especially evident during the administration of Ronald Reagan, when the policy even had a name. It was called the Kirkpatrick Doctrine, after Reagan’s ambassador to the UN, Jeane Kirkpatrick. It was based on the belief that a rightwing dictator was preferable to a leftwing leader, even a democratically elected one, because the former would help win the Cold War, while the latter might not.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks on 9/11, a similar doctrine took hold with terrorism replacing communism as the existential threat. Nine days after 9/11, President George W. Bush declared in a speech to Congress, “Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.” In practice this meant that any autocrat could invoke the threat of Islamist terrorism as a reason to receive American military aid. It was and remains a way of looking at the world that is as simplistic as it is binary. And it often makes matters worse.

In 2003, a writer in the Christian Science Monitor described what can happen: “[Bush] administration mismanagement of the war on terror has deeply undermined stability across Africa in the past year. In its African incarnation, that war has managed to produce almost exactly the opposite of what was intended. The administration has allowed African partner regimes to crack down on a wide range of Muslim groups . . . creating enemies where they previously didn’t exist.”

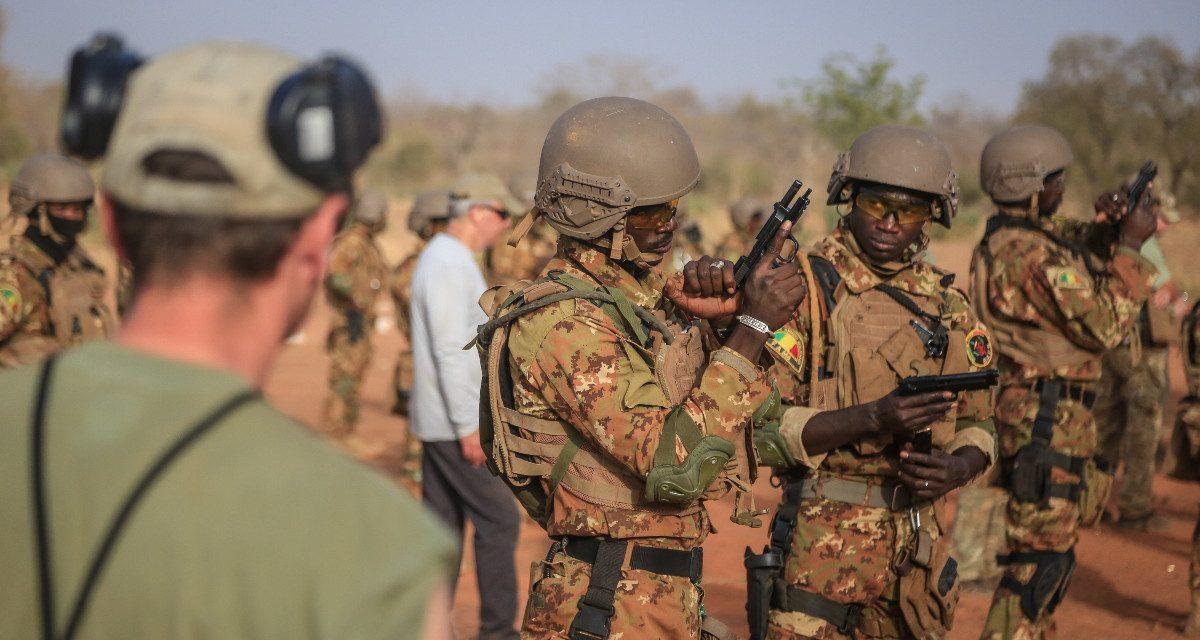

As the efforts to contain those enemies faltered, a broader approach was tried. In 2005 the Trans Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership was launched. The TSCTP was designed to be a “multiyear, interagency program to counter violent extremism by building the resilience of marginalized communities so that they can resist radicalization and terrorist recruitment, and to counter terrorism by building long-term security force counterterrorism capacity and regional security cooperation.” Labeled an all-of-government approach, the TSCTP has nonetheless been lopsidedly favorable to using military means to solve the problem. And it has failed.

The fact that violent extremism has continued to grow after seventeen years of the TSCTP and hundreds of millions of dollars is clear evidence of its lack of success. The program has even struggled to define its accomplishments and track where money went. As a 2014 GAO report pointed out, while US agencies had spent about half of the nearly $290 million allocated for TSCTP since 2009, they lacked the information necessary to evaluate the program’s performance and make management decisions.

A former senior official in the Bureau of African Affairs of the State Department had a harsher appraisal of the program. “I considered it a scam,” he told me. “When I asked people about success, they pointed to how many people were trained. In my view success is how much territory the bad guys control. The fact is, they now control much more.”

The inability to improve security, despite the TSCTP and scores of French and other countries’ soldiers being killed, demonstrates that the strategy is not working. That is because military efforts leave the fundamental causes of the problem unaddressed.

An updated version of the TSCTP that was enacted in 2022 tries to do that. The legislation explicitly recognized that “poor governance, political and economic marginalization, and lack of accountability for human rights abuses by security forces are drivers of extremism.” Congress gave the executive branch 180 days to come up with a plan that would combat the extremists, increase employment opportunities, girls’ education, women’s political participation, the capacity of local governments and civil society, and government transparency and accountability, and fight corruption. The contents of the plan are not public, but it will also not succeed. Understanding why requires considering why Mali is on the brink of becoming a failed state.

The Cause of the Problem

Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. Almost half the people live in extreme poverty and the gross domestic product per capita there is about 3 percent of that of the United States. But poverty abounds in the world and terrorism is not significantly higher in poor countries than in rich ones as demonstrated by a study done by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

What does matter is the quality of the government in the country. Looking at the ranking of indexes prepared by organizations that rate countries on various dimensions of governance makes clear that Mali is one of the worst-run countries in the world.

In terms of civil liberties and political rights, Freedom House categorized it as “not free.” Transparency International ranked it as 136 among 180 countries in its Corruption Perceptions Index. On the Ibrahim Index of overall governance, it came in at 31st out of 54 countries in Africa.

As the New York Times described it in a February 2022 article: “Beginning in Mali in 2012, terrorist groups across the Sahel took up arms against their governments, taking advantage of existing grievances held by marginalized communities, recruiting young men with few prospects and cowing villages in rural areas into submission.”

The article echoes the results of an extensive study recently published by the UN Development Programme. Interviews with hundreds of young men who had belonged to violent extremist groups found what had induced them to join was the lack of jobs, education, and faith in their government. Only 17 percent cited religion as a significant motivating factor. A 2015 Washington Post article also reported that a survey of nearly nine hundred Malians showed that “the most popular idea to resolve the crisis pointed not to a security response but to government reform.”

Despite these findings and the recognition in the TSCTP of the importance of political and economic issues, there has been little done to deal with corruption and other governance issues. The emphasis has been on the military option, but without the support of its people a government will not be able to defeat violent extremists. And when it comes to governments like the one in Mali, there is every reason to doubt whether it cares about its own people.

Why the War is Unwinnable

In the face of the extremist threat, Mali has greatly increased its defense spending. From $150 million, and 1.16 percent of GDP in 2013, it rose to nearly $600 million and 3.3 percent of GDP in 2020. More important than resources, however, is the question of motivation. As the army of Ukraine shows every day, a soldier who is defending his homeland has a greater will to fight than an invading army with large numbers of conscripts and criminals, low morale, and poor unit cohesion.

A personal commitment to the cause matters, but it is hard to see how a Malian soldier would believe defending the regime in power as a cause worth dying for. It is a government that governs badly and is the result of a revolving door of presidents who took office after questionable elections or coups. It is also a government that is to a degree at war against its own people and that has hired Russian mercenaries and given them free rein to assist in that war without regard to the welfare of civilians.

The UN peacekeepers will also never provide a solution or add anything other than casualties to the conflict. Following the failure of peacekeepers to protect civilians in Bosnia and elsewhere, the UN headquarters decided peacekeeping had to become more robust. In practice, this desire for robustness has led to ignoring the three principles that peacekeepers traditionally followed—remaining impartial, having the acceptance of all the parties to the conflict, and using force only for self-defense. Ignoring those principles have come at a cost.

The military contingents in MINUSMA, and the other four peacekeeping operations launched since the decision on robustness was made, are supposed to protect civilians and help the government gain control of more of its territory. That puts the peacekeepers potentially in combat roles and makes them targets for the extremists.

Peacekeepers should never be expected to be war fighters. One reason is that the twelve thousand soldiers in the military contingent in MINUSMA come from fifty-five different countries. Over 85 percent of them are from poor countries where the defense expenditure per soldier is about as low as in Mali. Despite the desire for robustness on the part of diplomats in New York, poorly equipped and poorly motivated foreign soldiers have even less incentive to put themselves at risk than Malian soldiers do.

Another problem is that even though MINUSMA is one of the largest and most expensive peacekeeping operations, it is spread too thin. In two smaller African countries, Liberia and Sierra Leone, there were peacekeeping missions that were considered successful. In the former, there was a peacekeeper for about every six square kilometers. In the latter it was one for every four square kilometers. In Mali, the ratio is one per 80 square kilometers.

Neither foreign soldiers nor peacekeepers will win the war against violent extremism. What might work is a nonmilitary approach, but it is unlikely to be seriously tried.

A Better Strategy—that Won’t Happen

Despite all the rhetoric, the United States and other donor countries that provide official development assistance have never been good at promoting democracy. As a recent report by the Westminster Foundation for Democracy explained, even though the world is in a prolonged democratic recession: “When countries decide where to send official development assistance (ODA) funding, whether the recipient is a democracy is not a big factor in their decisions. 79% of aid went to autocracies in 2019. . . . Democratic initiatives supported by Western states are often outweighed by their everyday engagements with authoritarian partners—from trade deals to joint security programmes.” While the United States suspended military aid to Mali in 2020 because of the coup that year, it continues to provide development aid and humanitarian assistance that amounted to $223 million in Fiscal Year 2021.

Without using ODA as leverage to improve governance, there is little chance that democracy will strengthen because authoritarian governments have no incentive or interest in governing better. In February 2023, the Eurasia Group, a leading consulting firm in political risk analysis, came out with a project called the Atlas of Impunity. It demonstrated a strong positive correlation between overall impunity and unaccountable governance, economic exploitation, and human rights abuse. The government in Mali, and those in most of the rest of the Sahel, scored high marks on the measurement of the degree to which they are immune to repercussions for their actions. Their interest is not in doing what’s best for their people and their countries. Their main goal is hanging on to power.

Because power is more important than peace to these governments, they will be unimpressed with the efforts of donor countries aimed at getting them to govern better. The kind of coercive diplomacy that might have any chance of making that happen is something donor countries are unwilling to try. And the argument will be made that it is necessary to accept an undemocratic government to confront a critical threat.

The central justification offered by Osama bin Laden for the 9/11 attacks was the stationing of American troops in Saudi Arabia to protect a corrupt monarchy. The possibility of a terrorist attack on the homeland originating from the Sahel seems remote. But renewing the provision of military aid and training to a government like the one in Mali might inspire a Sahelian version of bin Laden. And that would be one way to lose an unwinnable war.

Dennis Jett is a professor in the School of International Affairs at Penn State University. A former career diplomat, he served as ambassador in Peru and Mozambique, on the National Security Council, and in Argentina, Israel, Malawi, and Liberia. He is the author of four books on peacekeeping and American foreign policy as well as numerous other publications.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Spc. Peter Seidler, US Army

Lots of academic criticism with nothing constructive. How territories are controlled in Africa has been invented and verified long ago.

https://tnsr.org/2022/11/stabilization-lessons-from-the-british-empire/