The military loves Gettysburg. But why?

Isn’t it strange to fixate on an event in a war that happened over 150 years ago, fought on home soil, in Virginia, New Mexico, Tennessee and more, over slavery, in a society with 8,000 different types of money in use, featuring tactics that violate the core modern principle of cover and concealment? In short, these conditions are certain never to be replicated. So why do over a million visitors, including scores of thousands of military students, flock there every year?

I plead guilty. I’ve participated in perpetuating this trend, having visited a dozen times in my military career and taken many groups of soon-to-be officers to Gettysburg on Staff Rides. Essentially, I’ve concluded that while wars never repeat, warfare always rhymes. Wars share common features, so much that a modern American Iraq veteran, on visiting the spot where Italians and Austrians fought across the Italian Alps in 1916, reflected: “I have more in common with these Austrians and Italians who are buried under my feet than I do with a lot of contemporary society. There’s this bond of being a soldier…that transcends time.” More broadly, Sir Michael Howard once noted, “after all allowances have been made for historical differences, wars still resemble each other more than they resemble any other human activity.” War has a time-transporting and place-defying quality.

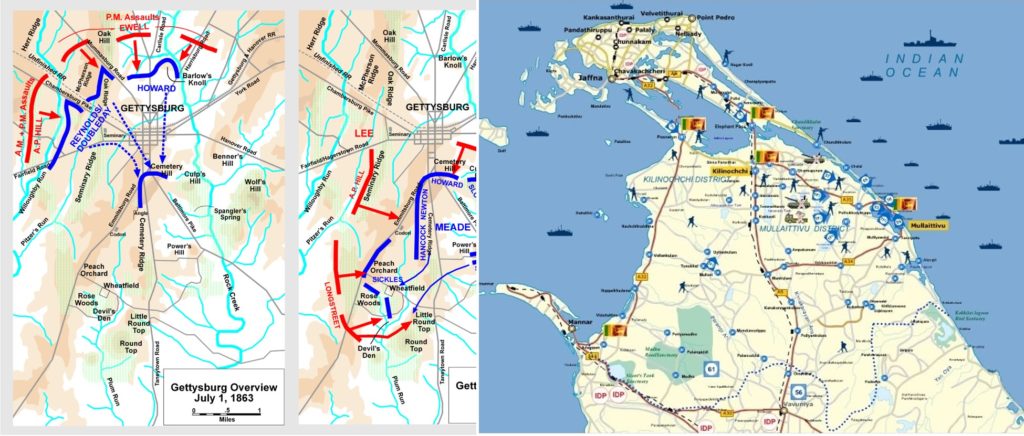

So let’s test Sir Michael’s hypothesis. Can a conflict as geographically and temporally distant as the recently-concluded, nearly three decade-long war in Sri Lanka, be usefully compared to the American Civil War in general and the Battle of Gettysburg in particular?

First, the strategic logic to the conflict. This one’s actually, perhaps, the easiest to connect – they’re both civil wars, fought across ethnic grievances, featuring a north-south division and power struggle between a national power block and local subsidiarity. An extension of politics through bloody and violent means.

Next, the two conflicts share moments of extreme sacrifice for military advantage. Gettysburg featured several distinct instances that would prove worthy examples. The first came on Gettysburg’s second day, nearing dusk, when a break in the Union line caused Major General Winfield Scott Hancock to send the 289 men of the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment to hold the line against a Confederate force of 1100 men. Later, Hancock reflected: “Reinforcements were coming on the run, but I knew that before they could reach the threatened point the Confederates, unless checked, would seize the position. I would have ordered that regiment in if I had known that every man would be killed. It had to be done.” Second Lieutenant William Lochren, of the First Minnesota and in the charge that day, wrote: “Every man realized in an instant what that order meant – death or wounds to us all; the sacrifice of the regiment to gain a few minutes’ time and save the position and probably the battlefield.” Duty came at a cost.

Just as it did the following day, on July 3, 1863, during Pickett’s Charge (also known as Longstreet’s Assault) – which cost the Confederates 6500 men of the 13,000 that charged into the solid Union line. Pickett’s men moved forward in a selfless sacrifice, just as individual, insurgent Tamil Tigers did during the civil war there. The University of Chicago Project on Security & Terrorism records 115 instances of suicide bombing in Sri Lanka, so many, that some consider this the birthplace of modern suicide terrorism. While contemporary readers might disregard this tactic as horrifying – when placed in comparison to those two examples from Gettysburg – can we not see any similarities between the Americans and Sri Lankans prepared to give their life for a cause they believed in? Of course, one must acknowledge these were qualitatively different; in Sri Lanka the bombings were generally indiscriminate (and many of the would-be bombers were forced recruits with no say in the matter) while Pickett’s Charge was discriminate and pointed at opposing military forces. But when one looks at the impact on the individual, for himself, and the known consequences of his action, the fact they knew they’d likely (or surely) die, there is at least a useful comparison here.

Third, these two conflicts share sorrow – the natural human response to tragedy. While the weapons might have been different, the effect on human tissue and the soul is the same. Consider this story from Gettysburg:

“One of the thousands of Southerners scattered in shallow graves across the battlefield was North Carolinian Charles Futch, shot in the head while fighting next to his sibling John, who never left his dying brother’s side. After burying him in an anonymous grave, a semi-literate John poured out his tortured feelings in a letter home: ‘Charly got kild and he suffered [a] gratdeal [and] I don’t want nothing to eat hardly for I am…sick all the time and half crazy. I never wanted to come home so bad in my life.’”

In Sri Lanka, after the war, the battlefield was everywhere and among the people – littered with the devastation wrought by high explosives, human shields, and decades of sons not returning to mothers. Even worse, as if it had never happened, the aftermath featured a common occurrence of silence. Post-conflict, Sri Lanka became a bleak society well-acquainted with the true meaning of “absolute” defeat, not all that dissimilar from the American South in 1866.

Sri Lanka has much to teach us, as the war there ended a mere seven years ago, was fought overseas, across ethnic divides, and featured suicide and small-unit tactics seen widely across current global conflict. This is what we ought to study when we study war.

Useful for proximity, military students should go to Gettysburg if they must, but all ought to make special effort to study modern wars like Sri Lanka’s. Both old and new wars carry similar features, as Sir Michael counseled, but for the professional military officer it seems more valuable to study across geography than to reach across time.