“A serious problem in planning against American doctrine is that the Americans do not read their manuals, nor do they feel any obligation to follow their doctrine.” This Soviet observation during the Cold War could easily apply to the Joint Concept for Competing, released last year by then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley. At ninety-one pages and over thirty thousand words the JCC is unlikely to be read by many serving personnel. That is a shame because it is an important document—so important it is now being updated by Gen. Milley’s successor General Charles Q. Brown.

The Joint Concept for Competing is a farsighted document with much to commend it. It builds on a legacy of innovative thinking that transplanted ideas from the world of special operations into mainstream defense strategy via its predecessor, the 2018 Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning. One of these ideas was to apply “systems thinking” to deal with the complexity of the competitive space below the threshold of war. This is a powerful concept, and by building on it, the authors of the next JCC can revolutionize and bring a durable advantage the United States’ approach to strategic competition.

First Things First: Why Systems Thinking?

Systems thinking is an approach to analyzing complex systems. Complex systems are open environments in which structure and agents interact to create emergent behavior that is often unpredictable. The competitive space below the threshold of war—sometimes called the gray zone—is a typical complex system. Private hackers steal data. Rogue ships damage pipelines and cables. Saboteurs damage train lines and burn down factories. Assassins for hire target industry executives. Proxy actors foment political unrest. Beijing uses its coast guard and economic might to coerce its neighbors. Russia uses bot farms to generate industrial-scale disinformation and hack elections. Iran’s proxy militias conduct military campaigns in the Middle East. North Korean hackers steal secrets. Complexity abounds—and compounds when these tools are used in “hybrid” combinations.

Systems thinking acknowledges the true nature of complex systems and treats them accordingly. Tried-and-tested systems thinking methods can be used to “win” the gray zone—or at least compete more effectively in this complex environment. These tools already exist but are rarely acknowledged or used. Part of the problem is thinking about complex systems seems abstract, even if the basic ideas are intuitive. As the late political scientist Robert Jervis explains in his 1997 book, System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life: “Although we all know that social life and politics constitute systems and that many outcomes are the unintended consequences of complex interactions, the basic ideas of systems do not come readily to mind and so often are ignored.” This is unfortunate because, as Robert Axelrod and Michael D. Cohen point out in their 2008 book, Harnessing Complexity: “Whether or not we are aware of it, we all intervene in complex systems.”

The JCC takes initial steps toward incorporating systems thinking but could go much further. The language and ideas of complex systems feature throughout. The central idea of the concept is to “view strategic competition as a complex set of interactions.” However, if the concept is actually influenced by systems thinking, there is little evidence of it. The extensive bibliography contains nothing relevant (the hand of John Maynard Keynes’ dead scribblers might well be at play here).

For example, take the concept’s three “supporting ideas.” These are based on systems principles, even if the document does not acknowledge it. The first—“expand the competitive mindset”—is akin to “forest thinking,” which means seeing the bigger picture to tackle challenges at the source. The second—“shape the competitive space”—refers to the power of “leverage,” another principle of systems thinking, which holds that some actions to intervene in systems are more powerful than others. The third supporting idea—“advance integrated campaigning”—borrows from the cybernetics principle of “requisite variety,” which requires sufficient levers to meet the complexity of the environment.

However, while the language and ideas are there, much more could be done to apply systems thinking in the JCC. These prospects are currently undermined by the reliance on established US military planning doctrine that pervades the JCC—particularly the concept’s centerpiece, the “structured approach for strategic competition.” The principles of military planning are largely unchanged since the Napoleonic Wars and not well suited to complex systems. The authors of version two of the Joint Concept for Competing can address these limitations and improve the concept by doing three specific things. The first is to clearly define what the United States and its allies are competing for. The second is to update traditional military planning concepts based on systems thinking principles. The third is to implement a twin-track framework to contend for near-term interests while shaping the broader environment to deliver strategic objectives.

Competing for the System

It is commonplace for officials to pronounce that the United States is embroiled in a strategic competition with China, but often it is not clear exactly what the United States is competing for. A systems thinking perspective suggests the competition is for the system itself. This basic insight is provided by Donella Meadows, who contrasts the leverage of rules and norms with merely moving pieces around the board: “Power over the rules is real power.”

The current JCC recognizes the significance of rules and norms when it says, “U.S. national security is founded on . . . leading and sustaining a stable and open international system.” But it does not follow through by making clear that the object of strategic competition is the system itself. As the political scientist Michael Mazarr clarifies, “At its core, the United States and China are competing to shape the foundational global system—the essential ideas, habits, and expectations that govern international politics.”

At an abstract level, competing for the system involves striving to shape the structure of the international order. Key elements are both observable—such as institutions, rules, relationships, and the strength of military and economic forces—and less tangible—such as cultural influence, reputation, and expectations. If strategy is about making simple rules, then rule number one of the JCC might be: Thou shalt compete for the system.

On a practical level, the JCC should guide practitioners implementing this rule. One analysis identifies several examples of this guidance. These could include campaign design principles—or simple rules that can be understood and implemented across the organization—analytic mechanisms for identifying and prioritizing actions with the greatest leverage, or generating campaigns that unfold over time. Our earlier analysis recommends “campaigning with the system in mind,” on the basis that culture is more important than strategy.

But even rules and norms must come from somewhere and serve a larger purpose. They come from paradigms—frameworks containing basic assumptions and ways of thinking. As Meadows says, “Paradigms are the sources of systems.” Realizing that paradigms exist is the holy grail of leverage in systems. Mazarr also applies this insight to the competition with China: “It is ultimately a competition of norms, narratives, and legitimacy; a contest to have predominant influence over the reigning global paradigm.” The JCC could use this insight too. Instead of citing Henry Kissinger’s chess-versus-Go analogy to promote a more expansive conception of strategy—which is useful but limited—it could use it to highlight the paradigms within which each game exists (not to mention the paradigm of using games as metaphors).

A Different Approach to Military Planning

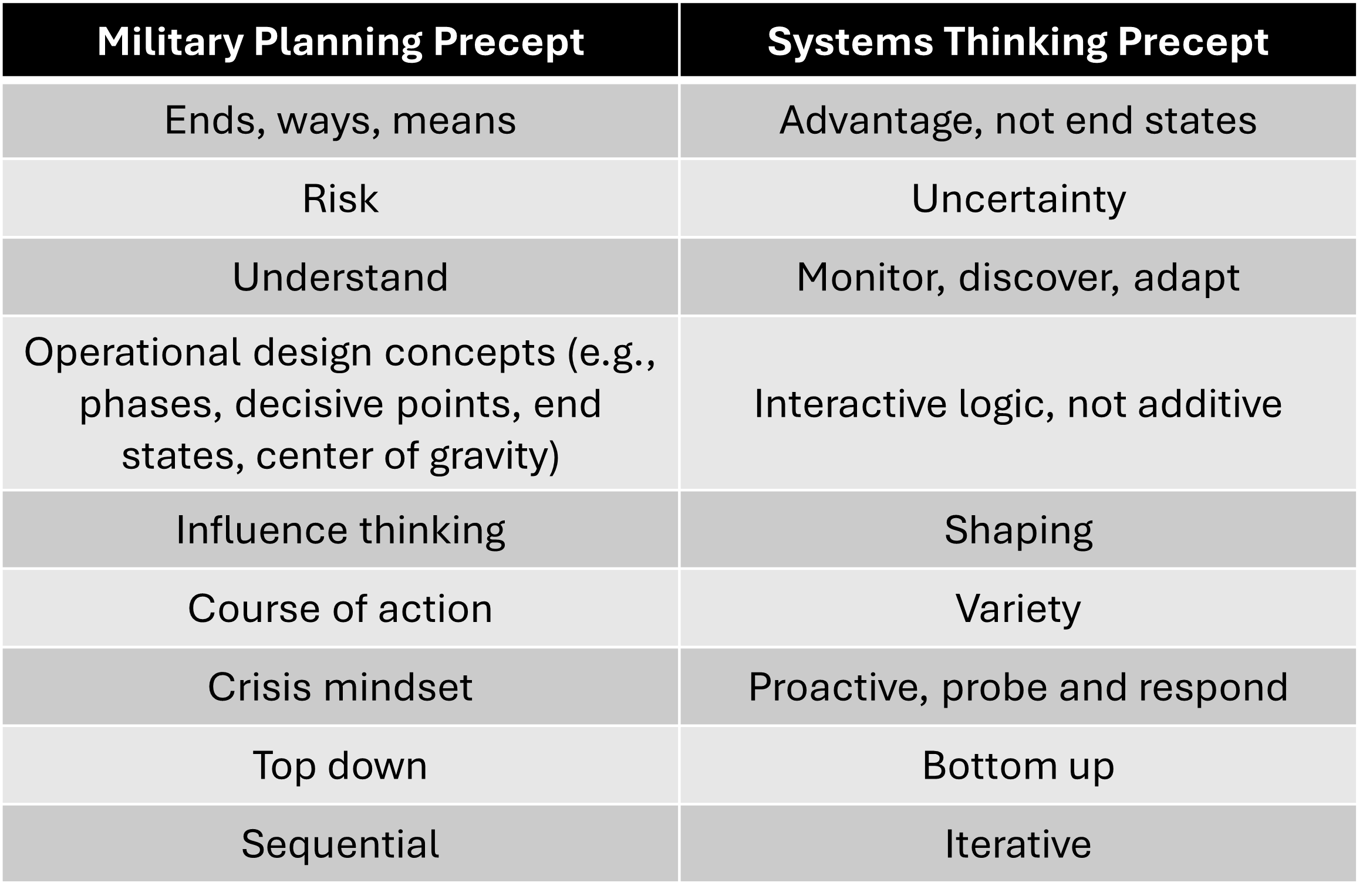

Our second suggestion is to replace the paradigm of traditional military planning concepts with principles based on systems thinking. The basic reason for this is that established military planning doctrine is designed for simple and complicated systems, not complex and chaotic ones. Table 1 contrasts established methods of military planning with more relevant systems thinking principles.

An alternative approach can be sketched by augmenting existing military planning precepts with a more explicit focus on systems. Our analysis for The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies took precepts from NATO’s military planning guidance, where they are called “operations design concepts.” The only difference between NATO and US doctrine is that the latter has seven planning steps instead of eight; the substance and methods are the same. This suggests our precepts can be directly applied to US doctrine. These are summarized in table 2 and briefly unpacked below.

Advantage, not end states. According to military planning doctrine, the application of ways and means to a problem will result in a desired end state, whereas a complexity-oriented approach treats strategy as a continuous and dynamic quest for advantage.

Uncertainty, not risk. US doctrine defines the occurrence risk of an “improbable” event as between 21 and 50 percent. But this concept of risk requires closed systems where probabilities can be reliably calculated, such as casino games. Planning in complex settings necessitates robustness under uncertainty and anticipation of surprises.

Monitoring and discovery, not understanding. Complex systems are often difficult to understand and can be highly unpredictable. Understandings therefore are transient and potentially fragile. Analytic approaches may need to seek general trends more than precise models, searching for patterns and relationships.

Interaction, not addition. Military planning precepts (e.g., phases, decisive conditions, end states, center of gravity) are often based on linear, additive logic. But with many actors and multicausal environments system effects warp actions and behaviors. Interactive logic has an advantage here, where actions and actors shape and are shaped by their environment.

Shaping, not influencing. Influence thinking is central to military planning. Actors are multifaceted, self-motivated, adaptive, and unpredictable, often acting counterintuitively, and so a powerful approach can be to shape the environment in which they operate, to nudge, incentivize, regulate, or constrain.

Variety, not a single course of action. Military planning doctrine is designed to present the commander with a single, preferred course of action. But there are advantages to variety and multilateralism, with success more about hedging bets and robustness than finding a killer app.

Mindset, organizational design, and process. A systems thinking mindset is proactive and curious: it is about probing and shaping the environment, involving stakeholders in positions to influence the system and prioritizing rapid iteration in response to feedback loops.

A Twin-Track Approach to Competing While Shaping

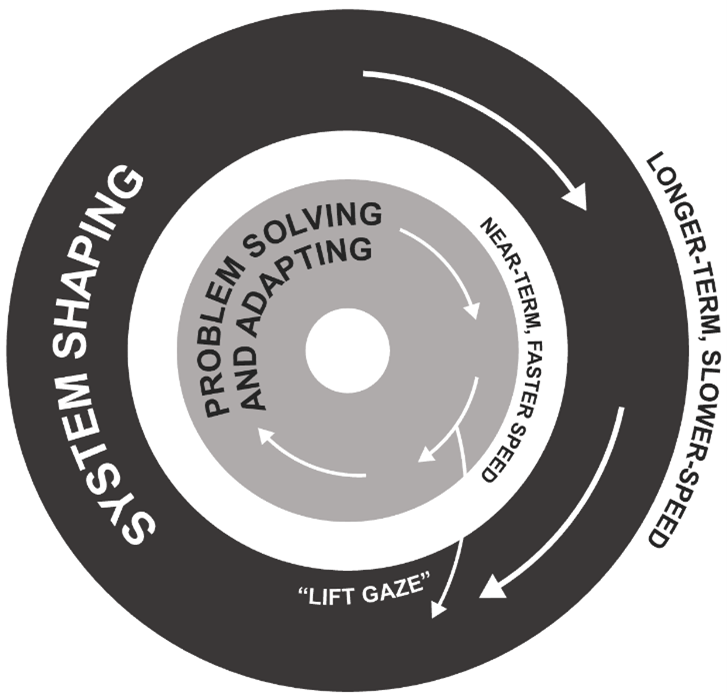

The previous two recommendations—competing for the system and rethinking traditional military planning concepts—demand an approach to implementation that serves two contrasting functions. The first is to compete with adversaries in the near term by gaining advantage, employing variety, adapting, shaping, probing, and iterating. The second is to ensure these actions contribute positively to broader, system-shaping efforts. Planners should be responsive across both scope of focus (from narrow and task-centered to broader and contextual) and time horizon. This can be challenging due to the natural tendency of large organizations to focus on the narrow and urgent over the broad and important. To support competing in both dimensions we offer a twin-track approach, shown in figure 1.

The inner track represents functions for problem solving and adapting. It has a shorter-term focus and moves at a faster speed. It includes identifying problems, diagnosing their causes, and developing and implementing responses. The objective of this activity is to restore equilibrium, stabilize the environment, and take incremental steps toward longer-term objectives.

The outer track is about system shaping. It has a broader aperture and longer-term horizon and can move at a slower pace. Work on this track includes developing strategic goals, future system designs, finding areas to intervene in the system, implementing interventions, and creating institutions, processes, or new stakeholder groups to make the changes stick. Effective leadership here is intersectoral leadership, across defense, the interagency, industry, and the whole of society.

To move from the inner to outer track planners lift their gazes to see more, both in space (more actors, institutions, and relationships) and over time (both upstream causes and downstream effects). And managing both tracks and the inevitable tensions between them will require innovative institutional design. The US government has a tradition of creating interagency mechanisms, such as the National Security Council, joint interagency task forces, interagency policy committees, and bodies for coordinating counterterrorism and cybersecurity. However, research from industry has found that because the objectives, processes, and cultures of such efforts differ, they should be distinct from each other and report on equal footing to the principal or overarching process above them. Existing mechanisms for interagency coordination may serve as platforms, but the focus of their work on each track should be clearly defined.

Less Is More

The 2018 Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning promised a revolution in how the United States uses its substantial military power. This was based on “the fundamental insight that the Joint Force plays an essential role . . . outside of the military sphere: competition below the threshold of armed conflict.” The 2023 Joint Concept for Competing took the baton and ran with it, but the revolution is not yet complete. In its recent report, the Commission on the National Defense Strategy saw “few indications that the U.S. government is consistently integrating tools of national security power.” (This was one of the main objectives of both concepts.) The next version of the Joint Concept for Competing gives General Brown and its authors the opportunity to finish the job by going all in on systems thinking. The complexity of modern strategic competition demands nothing less. Although if they want more people to read this version, they simply should write a shorter document. Less is always more.

Tim McDonald is associate policy researcher at RAND, and codirector of its Systems Transitions Applied Research (STAR) Initiative. He is a visiting researcher at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Sean Monaghan is a visiting fellow in the Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, where he focuses on NATO, European security, and defense. He has fifteen years of experience in the UK Ministry of Defence.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization the authors are affiliated with, including the RAND Corporation and its research sponsors, clients, and grantors.