The US Army’s announcement in October 2017 that it would form the Army Futures Command (AFC)—the “biggest reorganization in the Army since 1973”—was an acknowledgement of the need for significant institutional support to overcome innovation hurdles within the military. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley chose a permanent four-star command to manage this effort, instead of ad-hoc initiatives, because of the need to dedicate a single organization to “streamline and consolidate, and bring unity of command and purpose to the Army for the development of our future capabilities.”

As AFC expands and supplements its cross-functional teams (CFTs), it is vital that core design challenges are addressed or capability gaps will persist in modernization efforts. Specifically, there are four problems AFC needs to overcome to drive the modernization program the Army needs.

1. The Army’s Unbalanced Innovation Portfolio

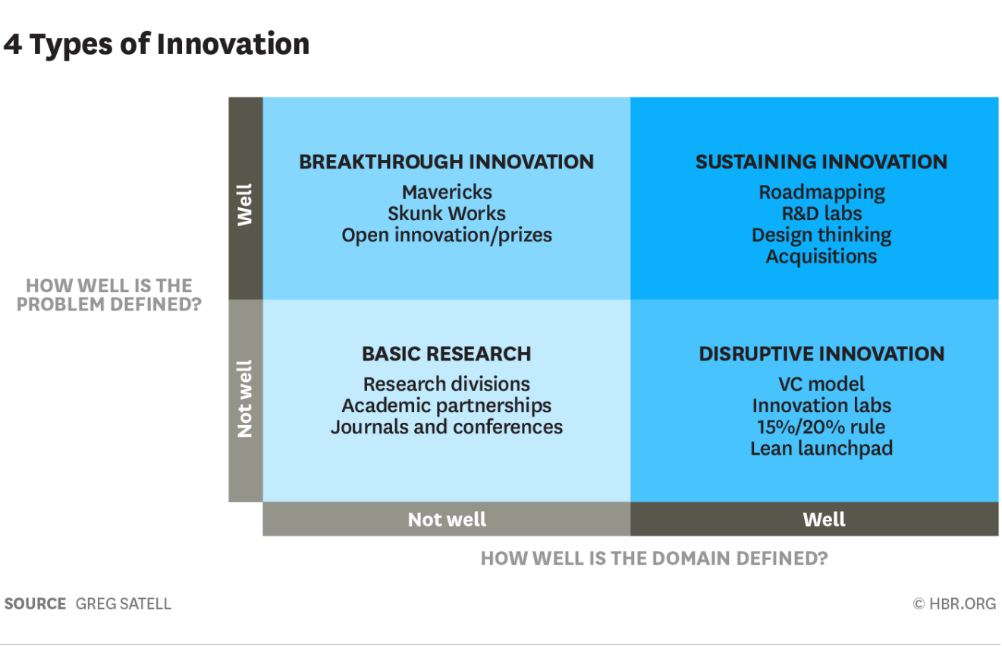

The first challenge in institutional innovation is balancing investments and priorities to create a comprehensive innovation portfolio targeting organizational needs. Harvard innovator Greg Satell developed a framework for educating leaders that defined four primary innovation quadrants and identified what methods best address their specific challenges:

i. Basic research is the raw conceptual work feeding later development, often associated with university research (e.g., developing a physics theorem that applies to microchip development).

ii. Sustaining innovation develops existing organizational capabilities, like increasing weapon ranges or processing speed, often through acquisition or incremental improvement.

iii. Breakthrough innovation focuses on easily defined problems with complex and multidisciplinary solutions ideal for collaborative events like hackathons (e.g., excess carbon dioxide and potential impact on climate change).

iv. Disruptive innovation deals with emerging technologies that begin as unsophisticated prototypes, which evolve and replace established technologies by meeting previously unserved needs (e.g., drones or artificial intelligence).

While quadrant priorities vary by industry, one element is constant: failure to diversify and balance investment invariably creates vulnerabilities.

This model places CFTs in the sustaining innovation quadrant as they focus on upgrading existing Army capabilities: long-range precision fires; next-generation combat vehicle; future vertical lift platforms; the Army network; air and missile defense capabilities; soldier lethality; precision navigation and timing; and synthetic training environments.

Army Secretary Mark Esper demonstrated his commitment to the CFTs, and the sustaining innovation quadrant, by personally eliminating or downgrading eight hundred other modernization programs. While CFTs offer benefits like clear outcomes, apparent need, and clear resource costs (AFC commands a $100 million internal budget and $30 billion modernization portfolio), heavy institutional investment in this quadrant causes AFC’s current innovation portfolio to be dangerously unbalanced. Although the Army can outsource basic research through groups like DARPA, federally funded research and development centers, and RAND, it is essential that AFC complements those efforts with aggressive investment in the remaining two quadrants: breakthrough and disruptive innovation.

The Department of Defense’s tendency to prioritize the sustaining innovation quadrant was visible in Obama era decisions to prioritize acquisition through components like the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx, now DIU), and Rapid Equipping Force (REF). While sustaining innovation is important, the vulnerabilities created by an unbalanced innovation portfolio lead experts like Elsa B. Kania from the Center for a New American Security to note that “the U.S. no longer possesses clear military-technical dominance, and China is rapidly emerging as a would-be superpower in science and technology.”

While Army Under Secretary Ryan McCarthy has recognized the power of disruptive innovation and its effects on existing organizations, noting that, “incubator hubs are really challenging these big corporations,” and exploring this quadrant has begun with efforts such as the Army Application Lab, much work remains. Strategies for closing the gap can be imported from initiatives like the Air Force’s Spark Tank and the Navy’s Athena Project, which harness disruptive innovation by allowing service members to pitch capability development ideas for institutional support in a forum that much like that of the television show Shark Tank. The Air Force and Marine Corps have also leveraged crowdsourcing to drive their disruptive innovation efforts with online platforms for commanders’ challenges that gather ideas from across the service.

Creating the CFTs and initial work with Army Application Lab are signs of progress; however, it is essential moving forward that institutional investment balances across the four innovation quadrants to prevent rivals from gaining an edge.

2. The Problem of Speed

Creating a four-star command is time consuming, and the CFTs’ approach, especially, is prone to delays in areas such as staffing, capability development, and fielding. Evidence of these delays can be seen in the ten-month lag between “standing up” the command in October 2017 and selecting Austin, Texas as its headquarters location in July 2018, and AFC’s goal of becoming fully operational in July 2019.

These manning delays are made more complex given the nature of mentor and senior leader oversight, which can create additional reporting requirements for the CFTs. Each CFT was assigned experienced general officer mentors to help navigate Pentagon and congressional hurdles, and while this provides institutional experience, mentors must balance this role against existing duties. This will likely cause delays during leadership and personnel transitions that force CFTs to regain momentum.

Administrative delays are compounded by contracting and development challenges. Even when solutions are readily accessible, like choosing a replacement for the M9 Beretta, the process can take many years: the initial announcement that the Army was seeking a new service pistol was made in 2011, competition began in 2015, and fielding was finally introduced in 2018.

While AFC commander Gen. John Murray states the CFTs have improved this process by decreasing the requirements phase down to twelve months from the former three to five years and accelerating the development phase, even this improved pace remains slow. Ambitious goals are fielding capabilities to warfighters “in the next three to five years”; however, history indicates “lightning fast” still entails around a five-year process.

For innovation goals with extensive development requirements, that five-year horizon turns into decades. This problem of speed is especially acute for programs in the science and technology (S&T) phase, where leaders like Kristopher Behler of the Army Research Laboratory admit many efforts are still in their infancy. After passing the S&T phase, projects must then pass through the development and programs phases before fielding.

These delays are made more complex by “lock in” challenges, explained by retired Maj. Gen. Robert Scales as translating “visions, concepts, and ideas into real things. . . . Lock too soon and the three variables [organizations, doctrine, and technologies] may not be developed sufficiently to fit into operational units. Lock too late and run the risk of making yesterday perfect.”

The result of these competing hurdles is that the current generation of soldiers may see no benefit from AFC efforts, exposing them to continued risk from outdated capabilities on the battlefield.

3. The Need for Better Talent Management

Innovation talent management requires skilled managers, effective project champions, and empowered individuals. Current Army personnel policies fail to achieve these goals.

A core challenge is the small pool of candidates allowed to serve on CFTs. Because assigned officers are generally between the ranks of major and colonel, only a small percentage of the force has the opportunity to serve in innovation roles. Since few military leaders have experience driving innovation projects, and the high rank requirement is a barrier to recruiting talent skilled in leading those projects, there is a capability gap. In cases where individuals have some readily applicable experience, AFC is competing for talent with established command tracks, and many career officers are disinterested in gambling with options that could negatively impact their career trajectory.

While many have criticized the Army’s strategic failure to manage talent, these challenges are especially acute for AFC as the organization’s success is predicated upon empowering the right people with the right tools. Until CFT recruitment targets innovative soldiers with a much wider range of ranks or current positions, hurdles like traditional career gates and assignment models will prevent agile talent management.

4. When It’s Time to Pivot

Although CFT priorities were chosen based on predictive models and the best judgment of experienced military leaders, cognitive biases and predictive inaccuracies risk creating modern equivalents of the Maginot Line. Even if we are correct in our current assessments, the slow movement of CFTs allows our adversaries to maneuver around our innovation programs and create new dilemmas for our Army.

The challenge facing AFC is that of balancing awareness of emerging technology with enough focus to shepherd new capabilities to the force. “Our competitive advantage has eroded in every domain of warfare, air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace,” then Defense Secretary James Mattis said last year, “and it is continuing to erode.” Restoring this competitive advantage requires agility throughout the innovation process, from initial priority setting to capability fielding, constantly driven by soldier feedback.

The primary organization for defining design requirements, and subsequent evaluation criteria, is the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, established to prevent services from launching redundant efforts. While it has improved the process, its rigid requirements borrow too heavily from Cold War–era institutional approaches and hinder pivoting to an approach that would prioritize soldier feedback.

The current process leverages feedback from soldiers, through efforts such as the US Joint Modernization Command, but does not do so until fielding. While this approach helps write doctrine for the use of technology, the late-stage focus prevents feedback from correcting core design flaws that may then not be discovered until well into the process, after enormous and unrecoverable investments of time and money.

A final challenge is that innovation targets that are too big for operational units to tackle and outside the scope of existing CFTs create an “innovation no man’s land.” These range from more effective software to improved logistics systems and training. However, it is exceptionally hard for tactical leaders to experiment and develop solutions given the additional budgetary burdens and personnel requirements of innovation efforts. The result is that AFC might succeed in generating intended capabilities, while pivoting too slowly to meet emerging threats and missing out on scores of innovation opportunities that would have eliminated inefficiencies and improved readiness and training quality. Until we create systems that efficiently centralize nominating enterprise-level opportunities, we risk falling behind in our effort to modernize.

The decision by leaders like Gen. Milley to centralize Army modernization efforts under one command demonstrates a commitment to military dominance in the next century. While AFC has gained some initial traction with the CFTs, it is essential that innovation investments create a rounded portfolio of tools that complement these enterprise-level initiatives. Failure to leverage the power of disruptive and breakthrough innovation risks creating room for our near-peer rivals to maneuver around us. Once the portfolio is rounded, the next step is ensuring that issues like speed, agility, and talent management are treated as AFC priorities, so they can reinforce America’s military advantages. A key step in that process is shifting the narrative and strategy to bring in contributors from across the Army and present modernization as a shared problem we must all address.

Capt. James Long is an Army infantry officer, MD5 Innovation Fellow, and experienced tactical innovator. He currently serves as an operations officer with United Nations Command Security Battalion–Joint Security Area. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Michael L. K. West, US Army

Interesting analysis regarding areas that need improvement about US Army modernization.

Well, here’s one…how about modernizing the infrastructure? Government buildings date to the 1940s and 1950s and into the Cold War. They are generally old, outdated, stale, and not very conductive of business. Sure, they may have been renovated and remodeled inside over the years, but compared to corporate with their brand new offices, skyscrapers, and purpose-designed buildings and garages, government buildings fail to boost morale and meet the needs of the workers. There is no garage. The cafeteria is small. The restrooms are small. The room sizes are the same. How is one supposed to modernize and innovate when the same building with the same basic overall footprint is used for decades?

If corporate needs to expand, corporate builds a new wing. If corporate needs to expand, corporate builds a new campus. If corporate needs to expand, corporate moves to a new location. Futures Command is a good example of this, moving to a new location, as is a few other defense innovation labs that started up inside other locations and some I believe have since shut down.

China and Russia build new government buildings, bases, and outposts with their wealth and drive. The US Army and DoD stay at the same forts, bases, and buildings. Some new construction is left unoccupied. This is evident with the hurricane that smashed Tyndall AFB and wrecked many hangars that were supposed to be hurricane-resistant but weren’t—old outdated infrastructure.

How then is the US Army supposed to modernize if they occupy the same basic footprint buildings even if generally remodeled on the inside? We’re talking about a massive influx of billions of dollars to modernize and expand the building infrastructure for the future: air force bases, ports, barracks, shipyards, forts, sewers, rooms, plumbing, federal buildings, labs, etc.

It’s been eight months since this article published and things are moving forward. The author failed to mention the Joint Warfighter Assessment (JWA) that occurs each year as a venue to supplement the CFTs’ focus on material solutions. A (not only) problem set exercised during JWA events is determining if the current modernization efforts are in line with defeating an adversary of the future and finding potential paths to explore to do so. JMC is responsible for developing the scenario with lots of agencies providing input to get the most of the events to shape future developments and identifying solutions that may or may not exist at this time.

The author is spot on with the military’s inability to capitalize on talent management as a drag on innovation. That’s nothing new within the Army. AFC should be trying to fend off the masses, but instead have a lower priority of fill than standard units. Likewise, those “masses” fight going to such an organization due to very likely negative career impacts.