During World War II, General George C. Marshall, the chief of staff of the US Army, sought an officer to form and lead an elite unit on a high-risk mission. He issued his instructions to find the right individual. “I want an officer for a secret and dangerous mission,” he reportedly said. “I want a West Point football player!”

The quote by Marshall, who himself played left tackle on the Virginia Military Institute football team, is celebrated to this day by the West Point football team. Apocryphal or not, it speaks to the notion that the benefits of competitive athletics extend well beyond the field of play. Or, in the words of General Douglas MacArthur, a former superintendent of the United States Military Academy, “Upon fields of friendly strife are sown the seeds that upon other fields, on other days, will bear the fruits of victory.” Of course, there is a massive chasm separating even the most competitive sporting events and the realities of combat. And yet, success in both endeavors share common elements. Leadership, courage, and cohesion—these are MacArthur’s seeds in the sporting arena and his fruits of victory in war and are vital to victory in both.

An Athlete in Ukraine

When Ukraine needed to defend its capital city against a full-scale Russian invasion on February 24, 2022, the head of the Ukrainian military, General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, did not ask for a football player, but he did get an athlete.

The mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko, had been a professional boxer. Nicknamed “Dr. Ironfist,” he had won forty-five professional fights—forty-one by knockout—and only lost two. He is one of only four three-time world heavyweight champions, alongside Lennox Lewis, Muhamad Ali, and Evander Holyfield.

Klitschko entered politics in 2004, playing a significant role in the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine. He made two failed mayoral runs in 2008 and 2012, was active in the 2014 Maidan Revolution, and shortly thereafter—like a boxer who rises from the canvas after being knocked down twice—ran for mayor a third time, this time successfully.

While interviewing Mayor Klitschko about the 2022 Battle of Kyiv, it was apparent that the thirty-eight-day battle had left an impact on him. Leading a major city like Kyiv, with a preinvasion population of over three million, is full of challenges. But none compare to leading one under siege by the second most powerful military in the world. As he spoke, it was also clear that a lifetime of competitive sports had helped to prepare him to lead his city in war.

Leadership

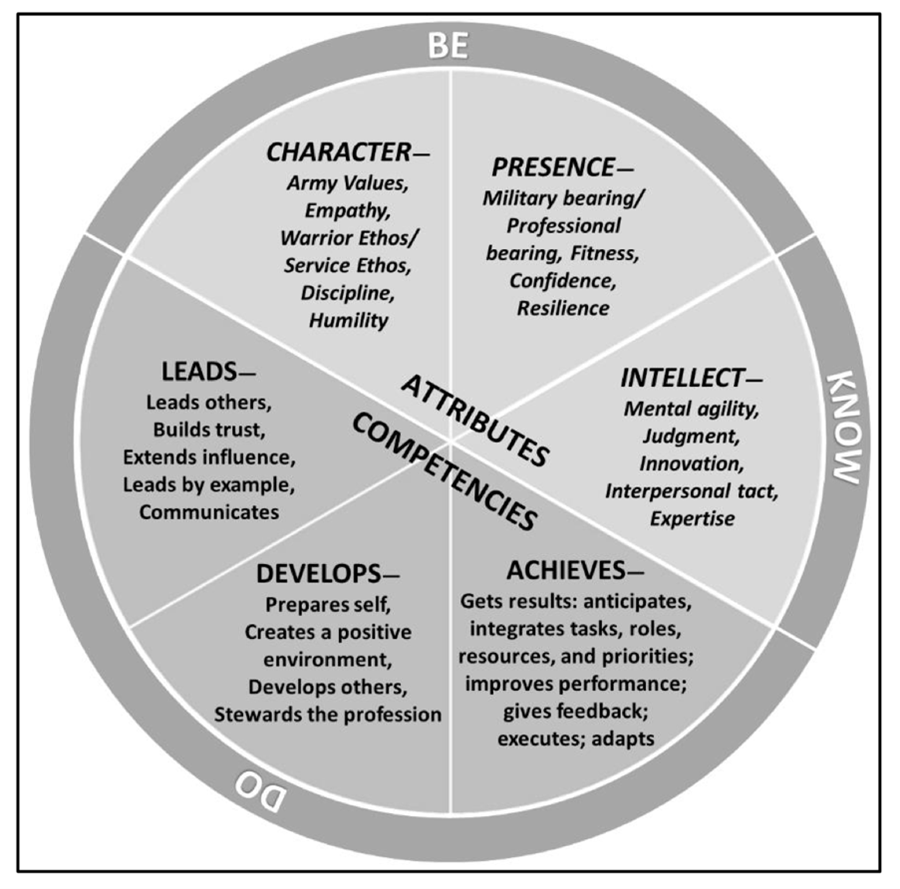

While leadership has certain context-dependent and difficult-to-define qualities, it is vital for any organization to identify its critical components. US Army leadership doctrine provides a model detailing specific leadership requirements. These requirements are broken up into two overarching categories: competencies, which are skills that are trained and developed, and attributes, which are personal characteristics, often molded through experience over time.

Leadership, then, requires individuals to constantly develop the skills and knowledge for their assigned positions—these are their competencies. But at any moment, leaders may find themselves in a situation in which their knowledge and skills are insufficient. This is when they must be able to rely on what they have gained from a lifetime of personal experiences—their attributes. That is especially important when called upon to lead in uncertainty—exactly the position in which Klitschko found himself when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Even as signs of coming a Russian invasion mounted, the Ukrainian government expected the heaviest fighting in the east, so there had been no real planning for the defense of Kyiv. When a fast-moving Russian force reached the outskirts of the city within the battle’s first twenty-four hours, defending the capital required leadership.

In addition to tracking, caring for, and providing services to Kyiv’s residents, Klitschko also served as a member of the Kyiv Defense Council. Recognizing quickly that the single mechanized brigade (and supporting assets) available to defend Kyiv was not enough, the council was hastily established to help organize the collective city’s defense. Klitschko and the other members of the council—senior military officers and civilian leaders— met daily to discuss both critical military topics—such as enemy locations and the need for checkpoints—and priorities for the city and its residents.

Few mayors in Klitschko’s position would have the skills necessary to lead a city and keep it running during a massive invasion. But he did have experience he could rely on, specifically the attributes he had gained from his career as a professional athlete.

When asked where he invested his time during the battle, Klitschko said that his number one priority was to keep the spirit of the people high. “I’m a fighter, you know,” Klitschko said. “I know it is not size that is so important, but the spirit.” The mayor knew that city’s residents needed to see him and that his presence needed to exhibit strength, confidence, and the will to fight by any means possible. Gone were the suits and ties he often wore as mayor, replaced with casual attire and often body armor, signaling his readiness to join the rest of the city in fighting if needed.

Courage

All people experience fear in war—the fear of being hurt, the fear of dying, the fear of failing, or the fear of the unknown. Courage is not the absence of fear but the ability to continue forward and accomplish the mission or task despite being afraid. Developing courage is a complex endeavor that requires a mix of knowledge, training, experience, and more.

One way to develop courage is to routinely face fearful situations, and one way to do that is in sports competition. Since 1907, passing boxing class has been a graduation requirement for West Point cadets. One of the reasons that the academy requires cadets to take boxing is to “put them in a fearful situation” to which they must react—to develop the courage to move forward and fight back even if they are experiencing high levels of fear.

As a boxer, Klitschko also understands that with danger, fear is always present. He knew the people of Kyiv were scared and he recognized that despite his own fear, his role as a leader was to help them combat their fear by being present, communicating confidence, and leading by example.

As many as one million of Kyiv’s residents fled the city and tens of thousands moved underground to avoid the bombing. At the height of the battle, Klitschko recalled visiting the Kyiv central train station, where an area had been set up for children to play while their parents awaited their train. A young boy was crying and screaming loudly. When the mayor asked others around him where the boy’s parents were, he was told that both had been killed the day prior and that no one had the heart to tell the child. Fear was pervasive in the city—from fear of being killed like the boy’s parents to fear of taking responsibility for the safety of others—and Klitschko knew that he had to do something. He worked with the staff to get the child care and comfort, because, as he said, “You have to have the courage [to do hard things].”

Cohesion

Cohesion, Army doctrine says, is “the bond of relationships and motivational factors that help a team stay together.” Good leaders recognize that prevailing in difficult situations requires cohesive teams working toward a common goal.

This is true in sports. Researchers have linked cohesion to team performance. But it is equally noticeable to watching fans—when a team goes on a winning streak and is described as playing loose and having fun together, for instance, or when an underperforming team is disjointed, its members out of sync with one another.

It is also true in war, which is why Klitschko so often speaks about the benefits of teamwork. When he moved around Kyiv in the opening days of the battle, Klitschko found citizens of all types—men, women, young, old—ready to join with others to fight the Russian invaders. He remembers an elderly man, over seventy, telling him, “I want to fight. I need a weapon.” The city handed tens of thousands of weapons to its residents and others to help defend the capital. Once armed with the means to fight back, Klitschko encouraged a sense of unity among the defenders, inspiring them to fight not for themselves, but for each other, their city, and their nation. “Every house, every street, every checkpoint, we will fight to the death if necessary,” he said.

While Marshall is said to have wanted a West Point football player, he would have been equally well served by a West Point hockey player, or basketball player, or wrestler. Every cadet at West Point must participate in competitive sports, whether varsity intercollegiate athletics, intercollegiate clubs, or company athletics. Beyond building physical fitness, this requirement does much more—enabling cadets to overcome adversity and face their fears, developing in them the attributes necessary to succeed off the field of play, instill a spirit of teamwork. Marshall and MacArthur understood this connection between sports and battlefield performance during World War II. Klitschko embodies it today.

The men and women who serve the United States in uniform will be confronted with challenges that test them, as individuals and as leaders. A wide range of factors—from military training to equipment to organizational structure and more—will combine to influence whether they will be prepared to meet those challenges. But among the contributors to their success will be the seeds sown on MacArthur’s fields of friendly strife.

Note: John Spencer interviewed Mayor Vitali Klitschko for this article in April 2023.

Colonel (CA) John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He served twenty-five years on active duty as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq. He was a member of the 2/75th Ranger Regiment when the development of the current US Army Combatives program was initiated and competed in the Best Ranger Competition. He is the author of the book Connected Soldiers: Life, Leadership, and Social Connections in Modern War, which focuses on the necessity of cohesion in war, and is the coauthor of Understanding Urban Warfare.

Colonel (retired) Liam Collins is executive director of the Madison Policy forum and a fellow at New America Foundation. He was the founding director of the Modern War Institute at West Point and served as a defense advisor to Ukraine from 2016 to 2018. He was an intercollegiate cross country and track athlete as a cadet and won the Army’s Best Ranger Competition in 2007. He earned two “V” devices for valor in combat and attributes his experience as an athlete as one of his most important developmental experiences that made him a successful leader in combat. He is coauthor of the book Understanding Urban Warfare.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: John Pellino, US Military Academy

FYI, Know, Be. Do was written by an Army LTC at TRADOC who was dying from cancer. He got the Leadership FM completed just before he passed away.

It’s a great framework for leadership.