Earlier this month, the Modern War Institute published an opinion piece, “The Tyranny of Battle Drill 6,” by retired Colonel Richard Hooker. In the article, Hooker argues that due to a culture of specialized urban tactics, conventional infantry soldiers should completely stop training to clear rooms. This is a dangerous position, one that skips over most of the context surrounding why the US Army prepares close-combat formations for urban warfare. In fact, the Army should be doing more to train its conventional infantry units for urban environments—including clearing rooms—not less.

Without Question, Infantry Will Have to Keep Clearing Rooms

The idea that infantry soldiers should stop training to clear rooms is just not informed by global trends, the Army’s history, or the character of modern warfare.

The world is urbanizing at unprecedented speed and scale. In 1970, only 1.3 billion of the world’s 3.7 billion people were urban dwellers. By 2020, over 4.3 billion (56 percent) of the global population of 7.7 billion were living in urban areas. The UN estimates that by 2050 two-thirds of the world will be urbanized. Across Western Europe, the Americas, Australia, Japan, and the Middle East today, more than 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas. Rapid urbanization, globalization, the fall of super- and regional powers, and resource scarcity have all contributed to turning political violence, intrastate war, and conflict in general into an urban-dominated phenomenon. The era of urban warfare is already here.

Cities are the economic and political centers of gravity for nations and historically have been the culminating sites of state-on-state, peer warfare. Both state-sponsored and nonstate actors see fighting in urban terrain and embedding within civilian populations as an effective countermeasure against Western maneuver, fires, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. The need for Army formations to close with and destroy enemy forces in buildings and rooms in support of the service’s mission statement—“defeating enemy ground forces and indefinitely seizing and controlling those things an adversary prizes most—its land, its resources and its population”—will only grow.

A Brief History of Room-Clearing Tactics and Battle Drill 6

The starting point of Hooker’s opposition is a video that went viral on social media in February 2021. The video shows soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division incorrectly conducting the infantry Battle Drill 6—“Enter and Clear a Room.” Despite Hooker’s argument against conventional infantry soldiers conducting room clearing, the soldiers in the video were not actually infantry soldiers. That might seem like a minor detail, but it becomes important when we examine the history and evolution of training on room clearing (using close-quarters battle tactics) done by the Army in the modern era.

Most urban warfare scholars attribute the beginnings of close-quarters battle (CQB, also sometimes called close-quarters combat) tactics to the failed raid to save Israeli Olympians in Munich in 1972. As Hooker notes, the CQB tactics developed and refined by counterterrorist units such as Special Forces Operational Detachment–Delta (SFOD-D) did pass into other special operations forces and eventually into conventional military units, both in the United States and around the world. What people often get wrong is that CQB is not the start of the US Army’s room-clearing tactics.

The US Army has a long history of doctrine reflecting its experience in urban environments. Sections of doctrine on urban warfare, to include tactics for use specifically in villages and towns, pre-date World War II, but post–World War II Army manuals are the ones that first start to codify room-clearing tactics. The Army had learned valuable lessons from its experiences in major World War II battles such as Aachen and Manila and in later city fights like Seoul during the Korean War and Hue in Vietnam.

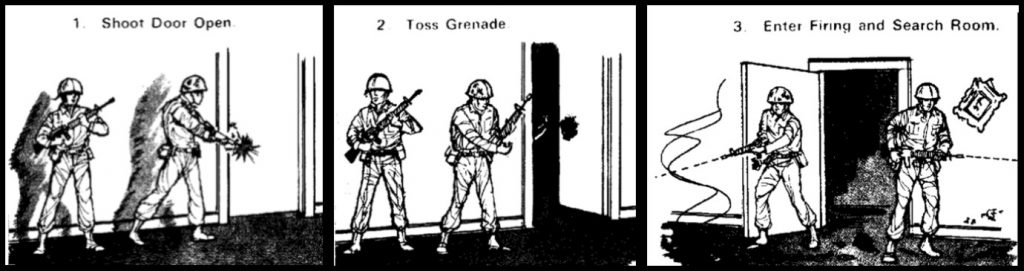

In 1979, one of the Army’s first urban warfare–specific manuals—Field Manual (FM) 90-10, Military Operations on Urbanized Terrain (MOUT)—described “how to attack and clear buildings” and is one of the Army’s first documented attempts to formalize tactics for room clearing using the lessons learned during and after World War II. The instructions were simple: Step 1, shoot door open. Step 2, toss grenade. Step 3, enter firing and search room.

In 1982, FM 90-10 subsequently spawned FM 90-10-1, An Infantryman’s Guide to Urban Combat, which had a section on how to conduct room clearing. It required an assault team of at least two soldiers. One would cook off a grenade and then throw it into the room. After detonation, one of the soldiers quickly entered and moved out of the doorway to one side or the other, sprayed the room with automatic fire, and then took up a position where he could observe the entire room while the other team member entered. A subsequent version of the manual issued in 1992—FM 90-10-1, An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas—described room clearing more deliberately with commands like “next man in, left” (or right). The tactic still recommended a two-man team.

One of the first appearances of battle drills (they were previously called common patrolling tasks) was in the 1992 FM 7-8, Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad, which included Battle Drill 6, “Enter Building/Clear Room.” The drill called for large amounts of suppressive fire from the squad approaching the building, followed by, again, a two-man team (now specified to be the squad leader and team leader), one on either side of the door, throwing a grenade in and then entering. One soldier would go left, the other right, but now doctrine specified that the soldiers should only engage identified or suspected enemy.

There is one other document in which infantry battle drills, urban warfare content, and room-clearing tactics can be found—the US Army Ranger School Handbook (a book produced for Ranger School students, but which heavily influences both Ranger and conventional infantry units). The 1992 Ranger Handbook listed and described Battle Drill 6 in the same way that it appeared in FM 7-8. The 2000 Ranger Handbook did not include Battle Drill 6, but it did include a new chapter on close-quarters combat, which included the use of the “four-man stack” technique to clear rooms—an important change from the previous doctrinal guidance that room clearing should be done with only two soldiers.

In 2003, the Army introduced “Warrior Tasks and Battle Drills” that it wanted all soldiers deploying to Iraq or Afghanistan to train. “Enter and Clear a Room” quickly became required for all soldiers. This may seem odd but based on the nature of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, it was not just infantry soldiers that were conducting missions requiring room clearing. It was regular practice for non-infantry units—armor, cavalry, engineers, and others—to be given ownership of battlespace, requiring them to conduct urban operations, especially raids on insurgent or terrorist targets. One of the most frequent offensive missions soldiers were conducting were intelligence-driven raids on targeted individuals in mostly permissive and often urban environments (meaning situations where the entire urban area was not hostile and the unit had identified the known or likely enemy position) where the enemy was intermixed with civilians. The Army’s tactics matched its requirements in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations.

In the next update of FM 7-8, which came in 2007 and renamed the manual FM 3-21.8, all infantry battle drills were removed and a new section titled “Clear a Room” described the same method using a “four-man fire team” that was detailed in the 2000 Ranger Handbook. When battle drills were written back into infantry doctrine in the 2016 version of FM 3-21.8, Battle Drills 6 had returned but with a slight name change—“Enter and Clear a Room”—and described the four-man stack method.

More than Just Doctrine and More than Just a Single Drill

The bigger problem represented by the video of the 10th Mountain Division soldiers is not the soldiers doing Battle Drill 6 wrong, but the multiple noncommissioned officers standing above them not identifying the major safety violations and tactics errors. Those mistakes should have been corrected in dry and blank training sessions long before live rounds were loaded into weapons.

Sparked by special operations forces’ training priorities and reinforced by experiences in 1993 during Operation Gothic Serpent—better known as Black Hawk Down—in Mogadishu, Somalia, the special operations community created multiple urban warfare courses. These courses, which still exist today—like the Special Forces Advanced Reconnaissance, Target Analysis, and Exploitation Techniques Course (SFARTAETC), Special Forces Advanced Urban Combat (SFAUC), and others—ensure CQB skills in special operations soldiers and noncommissioned officers are core competencies.

While conventional Army units slowly adopted CQB tactics into infantry doctrine and drills—and after 2000 required all soldiers train the new Battle Drill 6—they did not establish a robust system to ensure the tactics were learned, taught, and standardized across the greater Army. Neither the conventional infantry community nor the entire Army ever produced a school like the ones attended by special operations forces to ensure standardization of the drills. There are instances where individual units created programs—such as, interestingly a 10th Mountain Division Urban Combat Leader Course—but these efforts usually only lasted a short duration before being closed. Army units did send soldiers to the special operations courses, but it was never enough to ensure the Army had the resident knowledge to accurately train the tactics across the entire force. So without properly trained cadre from some type of urban master trainer school, unit training was often influenced by word of mouth from individual experiences more than a standardized tactic. So, it was not just the lack of ammo and training time Hooker identified that led to situations of Battle Drill 6 being done incorrectly. Actually, there are plenty of infantry and Army units that train, resource, and execute the drill to high levels of proficiency. It does take adequate time and resources, but it also takes trained noncommissioned officers. Battle Drill 6 (or any other urban tactics the Army wants to use) is easy to do but hard as hell to do well. It requires extensive training, a lot of shooting, and tons of live-fire drills. There are no shortcuts here.

Another main point Hooker missed is that Battle Drill 6 is not just for counterterrorism operations in permissive environments. The cases made against Battle Drill 6 are usually made by people who are addressing it in a single context, absent its high-intensity doctrinal history and usefulness. Yes, the Army missions in Iraq and Afghanistan did include years of executing intelligence-driven, precision raids in mainly permissive environments requiring complete surprise, speed, and entry from multiple unexpected directions described in CQB tactics. But Battle Drill 6, when applied as part of a full program of urban warfare training, can be adapted to match higher-intensity situations in a fully combined arms approach.

Nostalgia Can Be a Dangerous Thing

The tactical approach that Hooker seems to favor resembles a reversion to the tactics outlined in FM 90-10-1 along with the conceptual framework and assumptions about urban combat that underpinned them. FM 90-10 and FM 90-10-1 envisioned a depopulated and wrecked cityscape with few rules of engagement (ROE) restrictions on the application of firepower. It is a mental picture that evokes the Battle of Aachen (where the attacking Americans’ catchphrase for the operation was “Knock ’em all down” as they arguably not only did not avoid collateral damage, but sought to cause it), Seoul, Hue, or even Stalingrad. (The likeness with Stalingrad in particular is perhaps not surprising as many of the tactics presented in FM 90-10-1 seem closely related to those pioneered by Soviet General Vasily Chuikov’s 62nd Army as they ground down and ultimately destroyed German Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus’s forces in what many believe to have been the European Theater’s key inflection point during World War II.)

The problem is that the apocryphal city in FM 90-10-1 bears little resemblance to the teeming, pulsing, complex cities that the Army has actually fought in over the last thirty years. It did not take long in the modern era for this dissonance to give way to CQB. It was not just urban doctrine that was changing, but the world in which soldiers were deployed—a world with cities like Panama City, Panama; St. George, Grenada; and Mogadishu, Somalia where US forces found themselves operating.

When US forces assaulted Panama City in 1989 during Operation Just Cause, infantry units stepped into the world where FM 90-10-1 tactics conflicted with modern realities. Infantry in Panama City, like those in subsequent city fights, encountered people—hundreds of thousands of them—intermingled with enemy forces who almost invariably treated uniforms or identifying articles as quaint anachronisms. The “chainsaw” approach Hooker espoused—whereby infantry act as a chainsaw, not a scalpel—was inappropriate then and it is even more so now. While there is an interesting and quasi-theological argument that responsibility for civilian casualties lies with the side that undermines noncombatant immunity by wearing civilian clothing and embedding itself in the population, it is a proposition unlikely to gain significant traction in the current information environment. Troops in all our fights over the last thirty years have sought to minimize civilian casualties through the application of precise firepower and have still been pilloried when noncombatants have been killed. It does not take much guesswork to anticipate the reaction of global and domestic audiences when they receive nearly instant news through digital feeds of city inhabitants encountering a US Army infantry “chainsaw.” Drafted in an era before advancement in night vision, precision guided munitions, drones, and a full suite of modern combined arms weapons and tactics, FM 90-10-1 techniques proved profoundly unsuitable and inadequate for high-intensity warfare in densely populated urban areas like Panama, Mogadishu, Baghdad, and others.

While Hooker is completely correct that infantrymen should not be conducting hostage rescues or using counterterrorism environments as their mental starting points for future urban battles, reverting to the tactics of FM 90-10-1 only works if everyone encountered in a building is a combatant. This is not an assumption soldiers can make.

Relatedly, while the now-infamous 10th Mountain video shows significant safety and tactics shortfalls, the previous FM 90-10-1 methodology was arguably no safer. Room clearing with those techniques—their heavy use of grenades and bursts of fire in every room—put prodigious amounts of minimally directed metal in the air in confined spaces, with predictable results. As Hooker accurately notes, real bullets ricochet and go through walls, and in the lightly constructed, ramshackle buildings common across the developing world, so do grenade fragments. To be sure, when infantry have identified an enemy-held structure, the first tool to defeat that enemy should not be stacking outside the door. As soldiers have learned in recent battle, all available firepower and tools are used before entry. But eventually, the room still has to be cleared.

The Amorphous Nature of Battle Drill 6

Hooker seems to view Battle Drill 6 as not merely a room-clearing technique, but as a mental shorthand for an overarching philosophy of urban fighting that (he seems to believe) applies unnecessary limits on American firepower and places young infantry soldiers at elevated risk by preventing the full application of US fires and combat multipliers. This is a common mistake.

Much of this initial reticence stemmed from a misunderstanding of what Battle Drill 6 is—and what it is not. Put simply, Battle Drill 6 is a room-clearing battle drill, period. It does not encompass the entirety of CQB or urban warfare doctrine, nor does it in itself make any prescriptions regarding ROE, schemes of maneuver, or using (or abjuring) various combat enablers.

It instead offers the leader a scalable set of options applicable across multiple levels of combat intensity. The use of grenades is not forbidden—in fact Battle Drill 6 states, “If the unit is conducting high-intensity combat operations . . . a Soldier of the clearing team cooks off at least one grenade (fragmentation, concussion, or stun grenade)” and CQB tactics as originally envisioned make extensive use of explosive breaches from surprise locations. There is nothing in Battle Drill 6 that prevents a commander from, to borrow Hooker’s example, putting a main gun tank round through an entry point. There is nothing that bans the use of artillery, mortars, attack helicopters, or close-air support. If, however, these methods and tools are not appropriate under the tactical circumstances, infantry room-clearing tactics simply offer the leader a fuller repertoire of techniques to use in conjunction with all available assets.

There is also no inherent contradiction between CQB doctrine and the kind of bold, aggressive, and firepower-intensive tactics embodied in the 2003 “Thunder Run” or the 2004 Second Battle of Fallujah. Tactics are adapted to the context of the situation. While soldiers and Marines during the Second Battle of Fallujah did adapt their entry methods by using tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, mortars, and artillery to attack enemy fighters in buildings, they still had to search and clear the rooms of over thirty thousand buildings—in fact, one hundred squads had over two hundred firefights inside rooms.

Hooker seems to have inflated Battle Drill 6 into a more extensive doctrinal artifice on which he then hangs a set of concerns about excessive restrictions on US firepower that endanger our troops. This seems to conflate doctrine and tactics with specific leader decisions about ROE and the use of fires. CQB does not automatically restrict these enablers, though. Again, Battle Drill 6 is a room-clearing technique, nothing more. And it is definitely better overall, when trained properly and with varying conditions, than the one it replaced.

The Battle Drill 6 After Next?

Ultimately, Hooker is presenting a false choice. He would clearly hope to avoid having infantry fight in grinding, casualty-intensive urban combat and views conventional infantry as unsuited for room clearing in particular. His views are understandable, and he is treading a well-worn path here—writers stretching back to Sun Tzu have cautioned commanders against fighting in cities. What was often unavoidable in even overwhelmingly agrarian societies such as China during its Warring States period is even more likely so in today’s rapidly evolving urban settings. While perhaps things like artificial intelligence and other future technologies may in the not-too-distant future reshape our tactical options, for the time being infantrymen will have to fight in cities and will therefore need to clear rooms.

The real question is not whether to do Battle Drill 6 or CQB or not to. It is whether we decide that Battle Drill 6 and CQB are not germane to how infantrymen will fight in cities. If not, then what will replace them? What would be our conceptual framework going forward? Hooker rightly considers Fallujah an unattractive model for future urban fights, but for the wrong reasons. Over 90 percent of the city of Fallujah was emptied of its civilian population before the battle. That is unlikely to be the situation in future warfare. But which model is more palatable and more likely to achieve our desired political and military end states? Even with more destructive tactics of first placing high explosives into known enemy structures, rooms still have to be cleared.

What are the alternatives to room clearing? Complete destruction of cities using wide area artillery and aerial bombings such as Aleppo or Grozny when enemies embed into urban terrain?

Among the few techniques Hooker offered as alternatives were to simply use high explosives to clear rooms or conduct tactical callouts. It is not clear that applying even more firepower will be any safer for our troops. World War II armies learned to their detriment that reducing a building to rubble did not always simplify its clearance but rather provided additional rubble fortifications to clear. Ironically, the callout (surrounding a building or entire village with known enemy inside it and waiting for them to come out—essentially besieging it) was developed during counterinsurgency operations where the environments were mostly permissive and the mission variables (mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available, time available, and civil consideration) permitted sitting around and waiting for a single enemy to walk out. These conditions are also unlikely to be present during future urban warfare. Furthermore, a stationary unit conducting a callout is also subject to outside counterattack, indirect fires, snipers, and even vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices.

These significant disagreements with Hooker’s position and reasoning notwithstanding, there is value in his opinions starting a needed conversation. His article highlights tough questions we should be asking as more and more warfare has moved into urban areas. Soldiers should not be exclusively training room clearing under conditions of permissive environments or counterterrorist operations. Battle Drill 6 should not be the mental starting point or ending point for preparing Army formation for the wide range of tactics and skills needed in high-intensity urban combat. Urban warfare is a combined arms fight and requires frequent, realistic training to standard, and it requires soldiers to adapt to conditions that force a variety of tactics.

The bottom line is that soldiers will have to continue to clear rooms. That will not go away. In fact, the need will likely increase. Battle Drill 6 is useful when trained correctly and to a standard proficiency level as a tool to build on and adapt. Soldiers in the next battle will be required to close the distance to buildings—many fortified—clear them, and hold them using many tactics, techniques, and procedures based on the enemy, ROE, and urban environments they encounter.

Urban combat is tough, bloody, and difficult. It cannot be avoided. Urban battles consume time, supplies, and soldiers at an alarming rate. In the modern operational environment, however, we are likely to see many more battles in cities, not fewer. Despite Hooker’s skepticism, Army urban warfare tactics have actually evolved to match the character of warfare after the end of the World War II. We can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater in room clearing. We must continue to train for the full range of combat in densely populated urban areas.

John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, co-director of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He previously served as a fellow with the chief of staff of the Army’s Strategic Studies Group. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq.

Rich Hinman is a 1988 USMA graduate and a retired infantry officer with twenty-eight years of active and reserve service. He is currently a Foreign Service Officer with the Department of State serving in Kabul, Afghanistan.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or Department of State.

Image credit: Sgt. John Yountz, US Army

I see John does rightly and morally address the question of collateral damage – innocent deaths – which I deal with in my LinkedIn comment regarding this, below.

Urban warfare should be completely avoided – a city should be bypassed and isolated – "ripened." Air supremacy including drone supremacy enables supply to bypass city transportation hubs as well.

With Fallschirmjaeger – parachute troops – the Germans could have taken Stalingrad's supply and artillery support source: the eastern bank of the Volga, just as they had isolated and taken similarly situated Kiev.

My edited LinkedIn comment:

Kimmage in War on the Rocks is talking up regime-changing buffer state Belarus – regime change is an Act of War – and now these articles popping up about urban warfare.

In 2016, the Russians put 40 million of their civilians through nuclear war drills, expecting Hillary to win and then WW3 guaranteed.

Lately, they've been putting civilians though house-to-house fighting training, presumably including their Stalingrad – Chuikov: first the grenade goes in, after that the tommy gunner – experience, expecting another invasion from the (EU/NATO, this time) West.

At Stalingrad, Stalin refused to allow civilians – women and children – to evacuate. From Iraq, Libya, and Syria, that became a refugee flood. Like those in the Warsaw Ghetto, those in the Gaza Ghetto have no place to flee. And it looks like the Russian (and Belarusan) Slavs will be staying to fight for their towns.

And innocents of Ramadi, Fallujah, et al are being wracked by our permanent gene-damaging – thus literally genocidal – cancer-and-birth-defect-causing Depleted Uranium (DU) ordnance contamination.

In any case, Putin has fairly warned us that if we attack Russia (and we can presume that includes BeloRussia) it will be *total* war, and they will be nuking *our* cities.

Meanwhile, note John Kerry accurately observing that our and China's confrontation while Earth burns is "suicidal".

In my opinion, structure extrapolation is the primary problem here. You are so caught up in certain assumptions about how something is done that you get stuck in it. This ranges from the way in which one goes into rooms, whether one goes into rooms at all, to the question of what equipment soldiers need for this and everything is discussed without even clarifying the question beforehand, with which objective it is actually being done. Only because the future war will mainly be in the citys, this does not answer the question what the sense of room clearing is. For sure, in an city are more opportunities to clear rooms, but despite this, there is no true connection between the fact of future urban warfare and room clearing which can be an part of it – or not. There are so many thinkable alternatives to clear an room in complete different ways and this does also not answer the main-question: why at all? Tactics have to serve the higher purpose or else they are senseless.

Just as an example: if instead of soldiers I simply flood a building from the outside with micro-drones, then I can easily determine whether and where there are opponents. Either by clarifying and / or combating them or by acting agianst the micro-drones, which indirectly reveals the enemy presence.

Or instead of hand grenades, I use smoke grenades which I throw into the rooms and use thermal vision myself when clearing them.

Or I use CS gas instead of hand grenades, or an anesthetic gas (theoretically).

Or I blast a hole in the wall instead of using the door and generally avoid taking corridors, stairs and doors and just like the Israeli infantry work my way through the infrastructure at will in any direction.

Or I use a weapon which you can turn around the corner and which you can then fire out of full cover (also one of the means of choice in Israel in CQB).

etc etc etc

There are so many different possibilities, I haven't even started to enumerate all the conceivable ones here. Instead you hang on to a battle drill and the question of how human soldiers enter a room for room clearing. Instead, you should get rid of this completely. The more diverse you can act, the more creative and action-free soldiers are, the more freedom you give them, the more they start to surprise you positively with their own ingenious ideas.

Undoubtedly, much more urban and urban warfare has to be trained today. Instead of doing this in fixed, stiff drills and kata-training, one could simply offer it (just one example of many that would be possible here) as a playful leisure activity by enabling free play with color marking ammunition / laser etc. but not in the usual anarchy of this kind of fun, but with professional evaluation and the opportunity to learn and become better and get achievments (the winner gets an extra day free or moeny etc).

Now one can smile about it and doubt the military value of such a playful access to the CQB area, but better than the status quo, it is always – and much faster and cheaper because it happens by itself as a leisure activity and therefore with a complete different motivation.

Also in training and manouvere one should give much more freedom to the soldiers to experiment and one should forget all the scripted and strictly regulated action. Especially the urban cqb needs more than any other combat an open free floating brain. The more irregular one can fight, the better.

An excellent response to the initial article, and the evolution of US doctrine on the matter was particularly enlightening.

One point that I believe Col. Hooker was trying to raise, but failed to articulate, is that Battle Drill 6 remains the only common drill that directly deals with urban combat (both CQB and the umbrella MOÛT/Urban Operations). This does lead to a narrow view of the street/building as terrain by denying the rote soldier an alternative or adaptive view. Thus, the unit falls to the level of only what they’ve been taught.

Granted, we cannot simply add on “clear a stairway,” “maneuver along a street/hallway,” or “approach any given situation in a given way” battle drills without overwhelming the quality of training with a flood of minutiae. We can, however, increase the attention given to such fluid circumstances throughout NCOES (as well as encourage it in NCODP). Of course, this comes with the requisite time and empowerment for those NCOs to filter their insight to their joes – and the army bureaucracy has only been getting worse at trusting her men.

For a global force deployed around the world, and on-call 24/7/365, the US is pressed to send forces, "Boots," to respond to incidents ASAP if necessary.

Thus, if the situation calls for urban warfare, SAR, hostage rescue, reinforcement, evacuation, and offensive operations, you can bet that the closest force needs to learn and know CQB. In many situations, time is of the utmost importance and essence, and the DoD can't wait or deploy trained CQB infantry from CONUS. Often, CQB and 9-1-1 response is a job for the Marines and SOFs, but that ostensibly, isn't always the case.

Therefore, do US Army armor, artillery, chefs, pilots, sailors, logistics, Recruiters, mechanics, and officers need to learn and know CQB? Yes! If peer nations' armies vastly outnumber the US Army in troop count, then ALL US soldiers should learn proper CQB in case their fellow comrade gets kidnapped and dragged into a city. You bet that the fellow crew will attempt a rescue because it would be folly to fall back and wait for the properly trained CQB and SOF teams to arrive to conduct SAR because by the time that they do, the captured might be a victim.

And the training can be as simple as playing a simulation, video game CQB, practicing "sandbox tape rooms," or clearing the Mess Hall maze of overturned tables and hostages…train each week with CQB.

The DoD needs to understand that with budget cuts and personnel reductions for a more modernized force, CQB will become more important, and more emphasis and demand on the skills of the US soldiers will be required. The US Army isn't the US Air Force that always engages in "Over the horizon" and LRPF warfare, and while urban warfare is dangerous and can produce enormous causalities, if CONUS ever gets invaded in the unthinkable scenario, then the US President better believe that he's sending in active Army of National Guard troops that know what they're doing, are competent, and are well trained to accomplish the mission, even if it means that the nearest US Army soldier is a Recruiter. "Every Marine is a rifleman" needs to transfer and translate to the US Army soldier too because every US soldier is armed with a gun. Martial arts, bayonet skills, gas masks, target discrimination, ID signaling, medical care and evac, secure communications, joint operations, hydration, backup support, EOD and booby trap defusing, and gun/muzzle discipline are CQB essentials. Again, video games, Virtual Reality, and simulations can help lessen the burden and cost of CQB training.

The 10th Mountain CQB video was faulted and criticized for poor gun/muzzle discipline in CQB training, essentially, the live-fire soldiers pointed their carbines at the backs of their comrades entering the room—one itchy trigger finger or a surprise fright and the comrade can literally get shot in the back. As 10th MOUNTAIN, there is no real excuse saying that those soldiers were trained in rugged open mountain terrain warfare, and not CQB confines. If 10th Mountain was tasked to defend the HQ base, tent, FOB, airfield, or barracks, then you better believe that 10th Mountain soldiers need to have intrinsic well-honed CQB skills as required by the CO. And the same goes for chefs defending the Mess Hall, tankers defending the motor pool, mechanics defending the garage, logistics defending the tunnel, and National Guard defending the US Capitol. Every inch of America was contested "on that day" and every inch should learn to be defended by the DoD as the price of Real Estate has gone up in defense cost, even if it means a mechanic has to drop the wrench and pick up the carbine again.

If the US Army needs to work with the US Marines and cops to learn CQB skills, then that is what it takes to get the job done, because the local cops, law enforcement, FBI, HSI, ATF, college police, and SWAT don't quit until the area is cleared and secured, even if it takes all night and the next day to do so.

And the cycle needs to continue with new Recruits so assuage their fears of tunnel and cave warfare, stair climbing, CQB, vehicle combat, etc. I'm sure that there are a lot of highly trained and skilled Veterans who can come back and train US soldiers in CQB. The DoD needs to know and weed out those who can and cannot do CQB because no everyone is, or will be a Pro…but at least every US soldier needs to give it a try and know the basics.

John Spencer has written some good stuff, and hence deserves at least some benefit of the doubt. I’ll even play devil’s advocate for a minute.

Yes, Soldiers doing “Battle Drill 6” correctly (which is in doubt, regardless of trainee’s MOS) would be better than having them sitting around smoking and joking. The same could be said of pretty much anything you decide to call a “Battle Drill.” Instilling an attitude of aggressiveness and a readiness for action within Soldiers is always a good thing, as all would agree. And let’s be honest: inculcating fool’s courage in Soldiers headed for urban action would have value to a Commander facing tough choices.

Still, FWIW, I think Colonel Hooker got it right. When I received that training, it was to a miserably low standard. We weren’t prepared for a Memphis trailer park, let alone a Fallujah. And overall, it was definitely more a wannabe police procedure than something applicable to military actions. Obviously, something more along the lines of 1979’s FM 90-10 would have been vastly superior.

As with the original article, there’s a larger context. Any doctrine that’s been in place for decades is well-known to potential adversaries. As Ulrich Reinhardt suggests, we’re stuck on stupid, and we must realize an enemy will not be. Everyone should know you just can’t go running in through doors, except maybe in Memphis. Four-Soldier stack teams are the very antithesis of the painful lessons learned in the past, especially World War Two. There are combined-arms urban actions and there’s running up needless casualties; pick one.

But don’t take my word. Tim H’s comment on the original article offered the excellent advice of Arthur A. Durante, Jr, which includes “Urban combat is not an Infantry-only mission.” And “We must be very careful not to give our combat arms [S]oldiers the idea that all future urban combat at the tactical level will more closely resemble police SWAT team operations than the combat our fathers saw in Germany and the Philippines.”

More than ever, thank you, Colonel Hooker.

Room clearing “ high-intensity doctrinal history and usefulness”;

Yes, at racking up casualties.

Thank you for admitting its about avoiding bad PR for Collateral Damage. Because it is, and this isn’t Doctrine.

Its Religious Dogma.

We’ve moved beyond Doctrine long ago into Ritual Warfare, supported by lawfare. Behold the angry SGM, vowing to correct the Heresy of his hapless soldiers.

In the real military if we want to rid ourselves of this monstrosity we’ll have to declare it anathema, and punish senior leaders who take casualties using room clearing. Break a few careers, have the usual witch hunts, declare Room Clearing to be on the level of sexual harassment- its worse in truth as it maims and kills – and purge room clearing.

As room clearing is for hostage rescue the hostage rescue types can have a dispensation to keep training BD6.

Amen.

Room clearing should be avoided, however, in high intensity MOUT environment there are often no alternatives due to a lack of support in such combat.

At the Army CTCs, it appears that more casualties occur on the movement between buildings and the 'stacking' in preparation for entry to a single building, than actually occurs in clearing the building itself. We can't blow holes with tanks and breaching charges to achieve entry to the buildings in a training environment, so we revert to other training, learning bad lessons that will cost lives in battle. We allow troops to focus on FBI HRT tactics, and allow to atrophy the basic understanding and skills of suppressing the adjacent buildings providing interlocking supporting fires. We get distracted by the excitement of trying out our Delta Force moves, forgetting that we are a General Purpose formation.

Even in Tal Afar, Iraq, at the apex of COIN operations in urban environments, I remember infantry Soldiers, attempting to clear a solitary insurgent holed up in an otherwise empty building (as confirmed by the residents), entering and clearing in the finest fashion of 'for the glory of the Infantry'. After their SL was killed immediately, the decision was made to drop a 500lb bomb on the structure. Funny how the ROE seemed to change after a single casualty. Or maybe BD6 simply wasn't appropriate, but leaders were not accustomed to thinking of other solutions. As our unit moved to Ramadi, all leaders became much more open to leading a building clearing effort with a tank main gun round.

So I definitely support the notion that BD6 and the focus on this niche skillset, tends to focus our understanding of how to accomplish the urban fight. At least, up until it hurts, and then, COIN or LSCO, we go to what works best to keep troops safer in the grinder of the urban battlefield. We cannot afford to get squads, platoons and companies chewed up in a mere block in the urban fight. It negates every advantage we have. We need to use host nation forces, firepower, and technology to push through and beyond the urban environment in order to destroy the threat. And we need to leverage every part of the Information Advantage construct we can in the process, to beat the enemy to the public message.

Excellent comment, sir; thanks for sharing.

Both you and the article authors mention the information component of urban warfare. You’re certainly correct in believing it will be important. In fact, I believe it deserves more attention, and an honest assessment on how bad it will be.

We’re living in an increasingly Orwellian world. The American left becomes more openly Marxist every day, and they’re empowered by the media and social networking platforms. More than ever, dissent is becoming thoughtcrime. During the next major conflict, which will certainly include urban battle, I expect the American left to revert to the anti-war movement as never before. And they’ll certainly provide far more aid and comfort to the enemy than during the Vietnam years.

The article authors describe us as being in a disadvantageous position. I believe it will be much worse, and we’ll be facing a checkmate in one move. While enemy (mostly unmanned?) armored vehicles will be able to roll over civilian bodies with impunity, the ‘woke’ Pentagon will probably be receptive to placing cameras on US troops, in hopes of recording atrocities.

Maybe the situation won’t be that bad. But just how bad will it be?