In November, the US Army gifted an early, unexpected Christmas present for eight hundred noncommissioned officers. Because the Army bureaucracy had underestimated graduation rates from the Army’s recruiting school, these NCOs would be sent for eight weeks to Fort Knox, some within a week of receiving notification. After graduating, they would then have to uproot their families in the middle of a school year, have their spouses quit their jobs, and move to a possibly remote location to help solve the Army’s recruiting crisis.

Before sending these NCOs their orders, the Army did not verify with them if it made sense for their families, their career ambitions, or their current units of assignment. The bureaucrats who decided to upend these NCOs’ lives did not know if the NCOs were ideal candidates to be recruiters. Instead, they provided hundreds of NCOs a new reason to be cynical about the Army’s personnel policies and sent them into American society to sell the Army.

The Army’s impersonal, centralized personnel system not only hindered recruiting efforts, it also likely led to many of these NCOs considering leaving the Army. This story is an example of the Army asking the wrong question in its recruiting crisis. Instead of asking how it can increase recruiting, the Army should be asking how it can retain soldiers so that it does not need to churn through so many recruits.

To solve its manning problem, the Army must return to a long-term service model that values people over the efficiency of a centralized personnel system. Before the 1940s, the Army had a long-term service model, but with the transition to a mass Army of short-term draftees, it shifted to a centralized personnel systems based on scientific management. This centralized system relied on rigid career paths, competitive evaluations, and an up-or-out system of promotions. It prioritized efficient, centralized allocation of personnel at the cost of dehumanizing soldiers by treating them as interchangeable cogs to drive the green machine. In adopting these policies, the Army transitioned from a pre–World War II personnel system based on professionalism and long-term service to one of careerism and churn. To return to long-term service, the Army must promote retention by providing increased purpose, stability, and career satisfaction through decentralized, flexible personnel policies.

The 1940s Roots of the 2020s Recruiting Crisis

In the 1940s, the Army established a personnel system that assumed a steady stream of short-term soldiers. It was initially supported by conscription, and after the adoption of the all-volunteer force (AVF) in 1973, it was enabled by wage stagnation and a lack of economic opportunities particularly for Black Americans and southerners. These societal enablers of a short-term service model no longer exist, and long-term economic and society trends mean the recruiting environment is unlikely to improve.

The Army has been ramping up recruiting efforts after it missed its fiscal year 2022 recruiting goal by 25 percent, and yet in 2023, it still fell 10 percent short of its annual target of sixty-five thousand recruits. The Army has been trying to solve this problem through solutions such as a new three-star command, career fairs, and new “talent acquisition” jobs. Though even with these solutions in place, the Army expects to eventually reach just sixty thousand recruits.

Additional recruiting efforts already face diminishing returns. Already in 2018, the Army increased the number of recruiters and revamped its marketing to meet a shortfall of just 6,500 soldiers, but the problem only worsened. Back in 2015, Undersecretary of the Army Brad R. Carson recognized that increasing recruiting efforts could not maintain an unsustainable personnel system: “It is my firm belief that the current personnel system, which has satisfactorily served us well for 75 years now, has become outdated,” Carson said. “What once worked for us has now, in the 21st century, become unnecessarily inflexible, inefficient, and irreparable.”

The AVF was adopted in 1973 after its recommendation by the Gates Commission, which expected the Army to transition to a longer-term service model with turnover reducing from 26 percent a year to 17 percent a year. With the increased retention of such a model, the voluntary army would require fewer recruits, which would ensure its sustainability. The commission estimated that the military required 265,000 recruits each year to support a force level of 2.1 million. But instead, even with pay increases between 50 and 100 percent, turnover did not decrease, and the military found itself having to enlist up to 470,000 recruits each year. The Army struggled to meet these goals.

In 1977, a RAND report questioned the long-term sustainability of the AVF if the military did not reduce turnover. It found that the military’s personnel policies developed over the draft era focused on allowing ease of management rather than meeting the country’s requirements. The military wanted predictable career patterns for centralized management. It became so habituated to these processes that it kept them after the end of the draft. Voluntary service did not increase retention because the Army maintained its 1940s personnel policies.

Economic Progress Means the Recruiting Crisis will Persist

Since the inception of the AVF, there have been worries that economic growth would hamper recruitment, but fortuitous recessions and wage stagnation saved the AVF. As William King reported on the first year of the AVF, “The Army fell more than 23,000 soldiers short of its recruiting objectives.” He attributed improved performance in the AVF’s second year partly to adjustments in recruiting practices—but also, crucially, to an economic recession.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Army could attract working-class recruits due to working-class wages stagnating while military pay increased. An article on the twentieth anniversary of the AVF highlighted how recruiting benefited from deindustrialization: “Instead of competing against the lure of relatively high paying factory jobs, military recruiters could offer an alternative to low paying, dead-end jobs in the service industries. In fact, real wages of high school graduates fell through the decade of the 1980s.” However, in the last few years, working-class wages have increased and provided well-paying alternatives to enlistment.

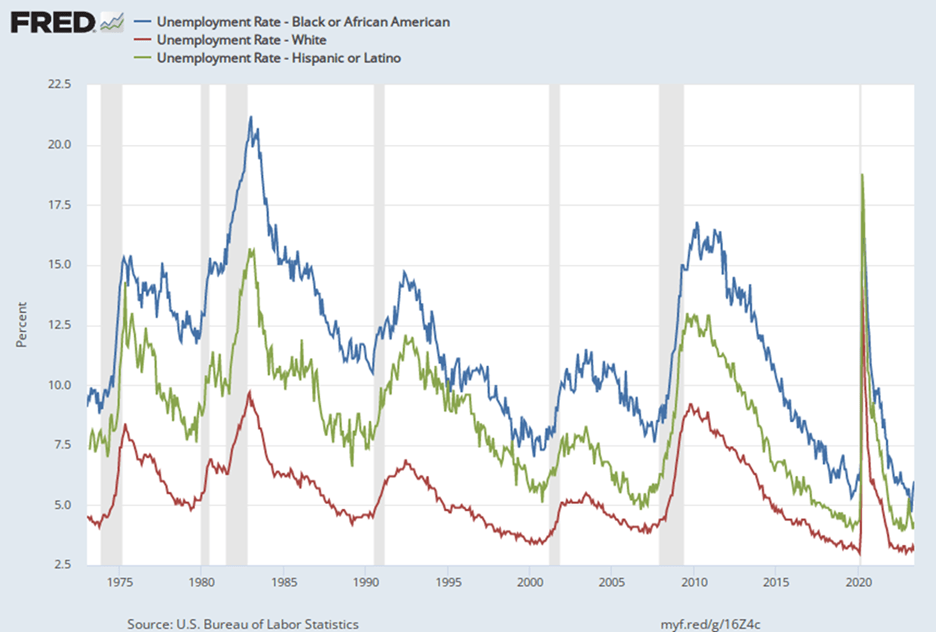

In addition to wage stagnation, the AVF initially benefited from the lack of opportunity for Black Americans. In 1977, they were 11 percent of the American population but 23.7 percent of the Army. They enlisted and reenlisted at much higher rates than White Americans. Now the Army can no longer rely on Black Americans lacking alternative opportunities. Their unemployment rate reached a record low of 4.7 percent in 2023.

Furthermore, since the 1800s, the Army has relied on the relatively impoverished South, which lagged in industrialization, to provide a disproportionate share of recruits. The South has been catching up to the rest of the country. In the 1980s, the Midwest had 25 percent more workers in industry than in the South. Now the regions are level on their percentage of workers in industry. With more economic opportunities in the South for the working class, the Army will find it a less lucrative source of recruits.

The Post-9/11 Wars delayed the Recruiting Crisis

In the early 2000s, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq mitigated the effects of societal changes on recruiting. Throughout much of American history, the public has rallied to the colors during wartime. But in peacetime, Americans have not viewed the Army as a high-prestige occupation. In 2021, after the withdrawal from Afghanistan brought the era of the post-9/11 wars to its denouement, only 9 percent of the American population between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one said they would consider military service, which was down from 13 percent in 2018 and a lower rate than any point during the post-9/11 era.

Without a war to fight, it can be hard to find purpose in military service. While some commentators turn to simplistic generational stereotypes to explain the current generation’s lack of interest in the military, it should be seen as return to a disinterested norm. As Morris Janowitz explained, in peacetime American society, “Entry into the military is often thought of as an effort to avoid the competitive realities of civil society. In the extreme view, the military profession is thought to be a berth for mediocrity.” Even in 1955, in a country full of veterans of World War II, the public ranked enlisted service as a low-prestige career. It placed fourteenth of sixteen working class occupations listed on a survey. Such surveys show that a lack of interest in service does not come from a lack of awareness. Those veterans of World War II might have thought military service was noble during wartime but did not want their children to deal with the Army’s personnel system during peacetime. Today, the same trend is occurring. The Army’s own survey in 2021 found that just 53 percent of active soldiers would recommend service to someone they cared about.

While in the past Army service may not have been attractive, before World War II, the Army could rely on those who joined to commit to long-term service. An illustrative data point is the collapse in retention of officers commissioned through West Point. Before World War I, only 12.5 percent of West Point officers had resigned their commissions before retirement. By World War II, a slight increase to 14.9 percent had resigned before retirement. By the 1950s, after the Army changed to scientific management personnel policies, between 20 and 25 percent of each class resigned after just five years of service. That relative trickle turned into a flood over the following decades. 62 percent of the class of 2004 resigned within ten years after commissioning. Not only West Point retention collapsed after the 1940s. In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower wrote a letter to Congress concerned with the fall in Army officer and enlisted retention, in which he cites that only 11.6 percent of personnel reenlisted in 1954 compared to 41.2 percent in 1949.

A Divisional System Will Increase Commitment to Long-Term Service

To transition to a long-term service model, the Army must move away from the personnel system codified in the 1940s that turned people into interchangeable cogs. The first step to increase commitment for a long-term service model would be to transition to a divisional system of assignment similar to the regimental system used by Commonwealth armies today.

While the US Army used a decentralized regimental system in the nineteenth century, the Army weakened it between the Spanish-American War and World War II. To rapidly create a mass Army, the service followed the path of many twentieth-century bureaucracies. James C. Scott explained in Seeing Like a State that modern bureaucracies sought to rationalize society through centralized, scientific management approaches. In their drive for efficiency, these approaches dehumanized populations, created inflexibility, and were often brutally ineffective.

During World War II, in a change from previous wars, American replacements traveled to combat theaters as individuals to efficiently replenish units. As they deployed, unsure of what unit they would join, soldiers complained they of being “herded like sheep” or “handled like so many sticks of wood.” After weeks of travel, they “wanted most of all to be identified with a unit.” Medical officers blamed the replacement system for psychological damage that led to high rates of psychiatric casualties before soldiers even reached the front. For a time, the Army discharged more men for psychiatric reasons then it received as replacements, leading General George Marshall to set up an investigation into the psychiatric crisis. Observing the crisis, Brigadier General Thomas Christian, commander of the Field Artillery School at Camp Roberts, recommended to the War Department G1 a transition to training and shipping out whole batteries and battalions to create cohesive units. The G1 replied to him that the Army would maintain the individual replacement system for administrative efficiency to meet its growing needs.

This practice of centrally assigning individuals continued after World War II with all its associated problems on morale and cohesion. The founder of sociology as an academic discipline, Émile Durkheim, argued that the increase in suicide in modern society was due to anomie—people becoming unmoored from their place in their community. After World War II, the Army emplaced a system of mandated moves every couple of years to ensure efficient manning. This system is a policy of enforced anomie. It is a probable cause for why, since 2011, even with investments into behavioral health services and the termination of combat operations, the Army’s suicide rate continues to increase. In seeking bureaucratic efficiency over putting people first, the Army breaks soldiers’ bonds of commitment to a “band of brothers” and breeds disenchantment.

The British and Canadian Armies still cultivate cohesion and commitment through their regimental systems—cohesion that eradicates anomie. Both armies also have lower suicide rates than the US Army. Over the last couple of decades, annual suicide rates per one hundred thousand soldiers were five in the Canadian Army, nine in the British Army, and twenty-eight in the US Army.

The cohesion of a regimental system also contributes to a greater dedication to long-term service. In 2022, 9 percent of the Canadian Armed Forces, 11 percent of the British Army, and 15 percent of the US Army separated from service. If the US Army had the retention rates of militaries with regimental systems, it would not face a recruiting crisis. With Canada’s retention rate, the US Army could maintain its current size with just 40,680 recruits a year.

In addition to increased commitment, cohesive armies are also more effective. Cohesion builds trust and initiative. When leaders know they will rely on the same subordinates for years, they will mentor them and invest in their development. Units that are together for years make long-term improvements to their systems and standard operating procedures. The bonds that soldiers develop over years of service build morale and create shared mental frameworks for their actions on the battlefield.

Before World War I, the French Army believed strongly in Ardant du Picq’s Etudes sur le combat, in which he stated that “Four brave men who do not know each other will not dare to attack a lion. Four less brave, but knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of mutual aid, will attack resolutely.” With such an understanding of the value of cohesion, their army fought bravely in World War I.

But in the 1930s, the French Army prioritized mass mobilization and firepower over cohesion in their doctrine of methodical battle, which took a scientific approach to war and treated their soldiers like interchangeable parts. In 1940, when French soldiers met the Germans at the decisive Battle of Sedan, they broke. The French commanders at the point of rupture blamed their men’s lack of will to fight on their lack of cohesion. On the other hand, German land forces had prioritized cohesion over bureaucratic efficiency. German recruits joined a specific regiment, attended basic training led by NCOs from that unit, and marched to the front to join their unit in company-sized elements. Due to their cohesion, they fought with initiative and courage.

A divisional system would also benefit the home front. It would allow families to stabilize and spouses to pursue careers. The Army will find it increasingly difficult to recruit and retain talented individuals whose similarly talented partners might naturally be unwilling to sacrifice their career for the Army. The antiquated assumption of the dutiful wife that follows her husband around is simply unreasonable and out of touch with today’s reality. This is not least because today’s Army has a mix of men and women in its ranks, unlike its World War II predecessor. Still, a little over 90 percent of Army spouses are women, and their experiences are indicative of a problem. Compared to the time of the AVF’s implementation, women have higher expectations for career fulfillment. In the 1960s, only 4 percent of women made the same or more than their husbands. Now, almost half do. A Department of Labor survey of military spouses showed that only 53 percent of Army wives participated in the labor market, many working transitory jobs on Army posts. They had three times the unemployment rate of women in the general population. In a 2021 Department of Defense survey, 48.3 percent of soldiers reported that the “impact of Army life on significant other’s career plans and goals” was an important reason to leave the Army, the second-highest reason soldiers consider leaving.

Decentralizing the Personnel System

Adopting a divisional system would allow the Army to implement the type of decentralized, flexible personnel system already used in the private sector and with Department of the Army civilians. Divisions could also be responsible for filling positions such as drill sergeants and recruiters, which would imbue them with a shared responsibility for ensuring competent soldiers arrived at their units. They would know that they would eventually go back to their divisions and serve with those new soldiers. Rather than relying on centralized decisions from Human Resources Command, divisions could fill vacancies by promoting from within or directly hiring from without. Without soldiers’ careers having to be easily legible for the centralized bureaucracy to make decisions, divisions could allow soldiers to follow flexible career paths.

Before World War II, soldiers could pursue diverse, flexible careers, driven by personal interactions. They had latitude to drive their own career paths. This latitude produced an officer corps that saw their profession as a calling. This corresponded to sociologist Max Weber’s ideal of a profession. He argued that “Unless we [as professionals] are working toward something specific, our actions aren’t anchored in any purpose of meaning.” Professionals obtain purpose through long-term commitment to solving a specific problem and by contributing to a professional body of knowledge.

Before World War II, flexible career paths in the US Army produced professional commitment and effectiveness. Janowitz identified that among the Army’s senior leaders during World War II, only 20 percent had followed a traditional career path, while 72.5 percent had followed an “adaptive” career path. As an example of the flexible career model existing before the war, Matthew Ridgeway taught Spanish at West Point for six years. Instead of traditional staff and command roles, he served most of the interwar years in Latin America and in the General Staff’s War Plans Division. His unconventional career produced an innovative and strategic mind, which Marshall recognized provided Ridgeway with enormous potential. He excelled as the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division without having done key developmental time at lower echelons. Before World War II, such diverse career paths were the norm for senior leaders, which created a diversity of thought at the top of the Army. Now such career paths are impossible.

To enable such career paths before World War II, officers like Ridgeway could go a decade without a promotion; there was no up-or-out system forcing soldiers out of service if they were not promoted on a rigid timeline. True professions do not use such counterproductive systems. Doctors are not forced out if they do not become hospital administrators. Professors do not lose tenure if they do not become department heads.

In a 1977 study of the AVF, RAND blamed the military’s attachment to the up-or-out system for preventing the transition to a long-term service model as the Gates Commission expected. During the draft era, the military tied experience to supervisory positions. It valued maintaining a pyramid rank structure required for managing draftees over developing experienced technicians.

The Army should allow soldiers to spend years becoming experts at a task. Imagine how effective a tank crew would be if they had trained together for five years or an advisor would be if he or she had worked with members of the same partner force for a decade, spoke their language, and knew their systems. By allowing such diverse careers before the 1940s, the Army produced effective leaders who were committed to their profession instead of careerists focused on efficiently moving through key developmental assignments.

End Corrosive Competitive Evaluations

By decentralizing the personnel system, the Army could eliminate corrosive competitive evaluations. The Army forces soldiers to compete against each other for their evaluations, a system that erodes professionalism and cohesion. In 1947 with DA Form 67-1, the Army implemented an evaluation system based in scientific management that forced evaluators to rank their subordinates against their peers. The Army desired a solution for centralized boards to reduce the number of senior officers as it cut down from its World War II size. This moved the service away from valuing an officer as a whole person. It eventually made NCO evaluations competitive as well. Before then, evaluations were qualitative. The Army diluted the competitive evaluation system in the 1980s and 1990s, but then sought to reinforce it as it cut down again in the mid-1990s. The strict box-checking system introduced in 2000 with DA Form 67-9 and quantitative numerations are the descendants of this scientific system to make the jobs of centralized promotion boards easier at the cost of fully appraising a soldier as a person.

Competitive evaluations are a discredited management practice. As The Economist reported, “Study after study suggests that they hurt overall performance, not least by lowering productivity. . . . Competitive ranking seems not just to reduce co-operation and foster selfishness but also to discourage risk-taking.” Groups that use them are less productive, have lower satisfaction, and exhibit increased status-seeking, careerist behaviors. The Army adopted them at the same time as American businesses in the post–World War II heyday of scientific management. But since then, General Electric, Amazon, Microsoft, and nearly all businesses that tried competitive evaluation systems have abandoned them due to their corrosive effects.

The Army needs to eliminate such practices. Competitive rankings facilitate centralized promotion boards but would not be needed if the Army used decentralized promotions managed within a divisional system. Divisions could do real talent management. Sitting on a divisional promotion board, decision-makers would know promotion candidates as individuals and not need to rely on numerical rankings.

The pressure of competitive ranking produces a workaholic culture that results in pervasive cynicism reflected across popular Army social media meme accounts. It is a work environment that drives people away. Before World War II, Army life was leisurely. It was a main draw and source of retention. The typical officer’s workday ended by noon. Officers averaged thirty hours of work a week. Such a schedule granted time for professional reading, writing, and mentoring. While the Army may not return to such a schedule, it should recognize that often the long hours that soldiers work are not to build true fighting capabilities but rather for theatrical displays of labor to outshine competing officers for that crucial “most qualified” evaluation rating.

The modern, high-pressure, careerist environment has not only undermined quality of life, but also degraded professional competence. Both Samuel Huntington and Janowitz praised the Army’s pre–World War II professional environment but worried about its postwar decline. Since the centralized personnel system was codified after the war, the Army has had a poor record in winning wars, it has shown little interest in learning from its defeats, and it has hazy thinking on how to fight future wars. By contrast, the old professional environment produced an Army that thought, invested in its soldiers, and won wars.

A Good Product Sells Itself

I do not propose a complete return to the pre–World War II personnel system, but a system inspired by its increased flexibility and commitment to long-term service. During the interwar years, the Army did not have decentralized promotions. It relied on centralized, time-in-service promotions that General Dwight Eisenhower testified to Congress were “unsatisfactory” and meant that “short of almost crime being committed by an officer, there were ineffectual ways of eliminating a man.” A decentralized system would not rely on time in service, up or out, or competitive evaluations.

Unfortunately, the Army continues to centralize decision-making with a drive for data-centric talent management, the latest buzzword offspring from the mid-twentieth-century’s scientific management. The Army needs to recognize that soldiers will not want to stay in an Army that treats them either as cogs in a machine or numbers on a spreadsheet.

The Army can take inspiration from its past to solve its manning crisis by returning to a professional, long-term service model. Such an Army would be more effective. It would reduce the amount of resources and soldiers committed to recruiting and basic training. It would have more committed soldiers and cohesive units that were not stuck in a Sisyphean cycle of retraining new arrivals. It would not have to recruit as many soldiers from a peacetime society with strong alternative opportunities to Army service. The Army must ask why it needs to churn through so many recruits. And, it needs to learn a good product sells itself. An Army that soldiers want to stay in will be an Army that society wants to join.

Maj. Robert G. Rose, US Army, serves as the operations officer for 3rd Squadron, 4th Security Forces Assistance Brigade. He holds an undergraduate degree from the United States Military Academy and graduate degrees from Harvard University and, as a Gates Scholar, from Cambridge University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Christopher Hennen, US Military Academy at West Point

How do you foster adaptation in combat if we create units of replacements instead of individual replacements who learn the most recent best practices from the “old guys.”

How do we guard against stagnation or “the ways it’s done” group think in garrison which risks some units being stellar and others not so much? See the guard as an an example of both problem and solution.

How do we keep premium living locations open for people to cycle through? The biggest decision point of assignment choice is location for the officer AIM marketplace.

A lot going on in here.

Good points:

-need to find a way to keep soldiers in the communities they desire for longer(especially important with a professional spouse)

-lack of motivation to be in a peace time army

-competitive rating schemes can have a negative effect

Things that need to be addressed:

-military is already full of nepotism; moving to a qualitative non-competitive review doesn’t solve that. Recommendation: create an evaluation system that greatly rewards peer and subordinate feedback

-with technology, do we really need a force this large currently? We have branches that have little value (see civil affairs internal assessment). Can we downsize and still maintain a volunteer force?

-can we change public perception of military with the help of veterans? The service can greatly change someone’s life for the better, how can we more effectively get the message out?

-how do we better identify the detractors of service? Can we implement an exit interview for all soldiers leaving?

Would love to chat more

Excellent essay. I was prepared to counter with my idea that the Army should be depending on Guard more during the so called "peacetime". But by the end of the article, I realize that's just another means to get to the same end, because the National Guard units effectively ARE the last remnants of a regimental system in the US, where one stays in one location, sticks with one's brothers, and while competitive evaluation is still present, some of the harshness of up or out is rounded off.

To add, if they values people, they must also hold toxic leaders accountable. That is another reasoning we can’t maintain SMs and talent in the Service. Strategically, it hurts the Nation.

The Army as well as the other services need to learn from the Marines. Maintain high standards and not lower them. Grooming standards, overweight, physical fitness are deplorable. I don't hear that Marines have trouble meeting their recruiting goals. The only service which exemplifies Pride are the Marines. Young men and women want to be challenged.

Maybe one of the reasons is, they see how the Veterans are treated and what they go through trying to get help

This absolutely. I don't think I've known a single vet that told any young hopeful they should join,or that if offered the chance they would do it again.

The Soldier in the supposed future Army has the GI Bill after 4 years, or limited advancement prospects if everyone stays in.

Unlike previous eras, that Soldier can also expect to deploy and otherwise work pretty hard to be spending most of their career at a junior rank.

I think there should be some opportunity for those who want to stay in even if they won't advance, but we can't retain everyone or there won't be room to promote the good ones who'll otherwise get out.

I Love the new uniforms. Like my WWII Dad wore.

As a former Army Recruiter, it’s my opinion that the Army pays a lot a attention and money on quantity of Recruiters rather than the quality of them. Trash the selection process as well as the way they are mentored upon arrival. Observe the way Marines do it… Chief M

During peace time, platoon or company size elements could rotate in and out of units to reduce stagnation, cross training in other jobs to eliminate stagnation. Some soldiers reach a certain rank and that is as high as they need to go, doesn't mean that they haven't got more to contribute, just means sergeant or captain is the level they need to stay at. A very experienced platoon sergeant that has the desire to create better NCO'S is rare individual and Army needs to find a way to keep individuals in key positions like this.

As for recruiting for the Army I am a retired OOR5PV7 with sixteen years in recruiting, I can't remember the last time I saw a commercial on the local TV station or heard a commercial on the radio, you have to plant the seed first.

Join the army. After 2 years trip over a tent peg and get a $4000 per month 'disability' payment.

A whole new dependent class for the taxpayer to support.

Go back to conscription with a core of professionals. Cheaper. The next war like Ukraine is fighting will need lots of people.

There will always be and have always been exceptions.

No pension lose wars that's it in a nutshell.

How can we expect young people to want to serve in any organization that puts political correctness first.

Recruiting company command was the worst assignment I ever had. It scarred my mental health and my emotional well being It put a dent in my career after a pretty stellar beginning The NCOs hated it also It is not the job you come into the Army for. You are randomly hijacked and forced into it After working yourself to death to get qualified soldiers in, then some ignorant hot head officer or NCO drives them out. They have no clue what went into getting that new soldier in Most officers and NCOs have poor leadership skills which in turn affects a soldiers desire to stay in. The commander assigns retention as an "extra duty" to some NCO and then wash their hands of it. Leave it to someone else to worry about having enough soldiers. Make them accountable for retention

In most platoons, for one E7, there are three E6. For each of them, two E5 (6). For each of them three or four E1-4 (24). It hurts (and ultimately ends) your career to not promote. It hurts your NCOER if you do promote but work in a slot below your grade. Even if you could be a career private, the pay is terrible. It's suitable for a young person in the barracks with no responsibilities outside of work. It's not suitable for a career and raising a family. The Army relies on one-and-done contracts to support this model, and those are three big changes to make before improved retention can be the answer.

Randomly hijacked is exactly how I felt when I was selected for Recruiting Bn Ops job out of the tactical Army. Had zero desire to have anything to do with it. Ended up being my terminal job.

As with all of these articles, interesting insights, some of which I agree with and some I don't.

I've seen as I've gone through prime recruiting age that the modern army wants consistent stats across the board, this excludes otherwise qualified individuals. I have health issues. I'm not going to be an outstanding warfighter, or even not-a-hinderance on the battlefield, but that doesn't mean I can't contribute.

I'm excellent at my highly technical field, and am also great at teaching it to new people, sitting in a chair in an air conditioned warehouse in Oklahoma, not on the front lines overseas. Let me be a teacher at the school, let me be a subject matter expert at the repair depot, there's great ways that a dude with asthma can contribute to the war effort, especially the next war, without rucking through a forest.

Part of what the private sector is getting much better at these days is ignoring the requirements if it doesn't matter for doing your job. Oh, we need a college degree to be hired for this role? Well, you can substitute education with experience. The Army doesn't do that, it treats everyone as if they will eventually be needed on the front lines in WWIII, so we gotta check every box in order for you to enter. We can't ignore the asthma thing, because everyone will be uprooted and sent to the front lines when war breaks out.

Get the right people in the right job, and open the jobs for the right people to find. People flourish when they lock in like a puzzle piece, but if you treat everyone like a square for efficient stacking and interchangeability, the puzzle pieces don't click.

We need to realize that a modern war is going to need more than just numbers of people, it will need highly skilled people doing their job at a high level. The impact to the organization is what matters, not ticking a box at the recruiters office. You want your numbers? Work on finding the right people for the right job, not checking all "yes" on a form. It'll get you a more capable army.

@Donald

It seems you’re making several bold claims about negative outcomes of a decentralized system without offering evidence or examples of that actually occurring. The article articulated separate points about basic training as a unit and the ability to adapt and learn from experience, and offered a solution in the form of basic training NCOs coming from those units themselves (to have a vested interest in the development of Soldiers that would be coming to their division). These NCOs are the ‘old guys’ that you can learn from as you come up in the Army, regardless of which process you endorse.

The problem of stagnation and doing things ‘the way it’s done’ is already prevalent, and is often a result of over reliance on extrinsic motivating factors, which have been thoroughly studied and proven to motivate less creative thinking. And it is often the ‘old guys’ at a unit that are the most jaded, responding with ‘it is what it is’, not the young and idealistic Soldier who recently entered service. Humans are much more motivated to help those close to them and improve their lot in life when they are able to build that life (and most importantly, to continue building that life). This is precisely what the author is describing as the solution the stagnation, lack of motivation, and distrust in Army personnel policies.

When considering ‘premium living locations’, perhaps the answer is not ‘give everyone a few years in a good spot’ but rather ‘make every spot good’. If we invest not only in the division, its assets, training environment, and personnel, but also the surrounding community, then we can all grow together and create the locations we want to live. And if it turns out no one wants to live at [insert wherever you think is suboptimal/terrible], maybe that tells the people running the place that they need to do better, or tells the Army that it ought to invest in finding a different location.

And all that aside, the Army is built on its people, and it certainly doesn’t put them first. Some people like the mountains, some like the ocean. Some like to get their hands dirty working on trucks, while others enjoying working at a computer managing files and awards, or leading teams, or making decisions. Why not at least try to align their desires with the goals and functions of the organization?

The military is always going to have a high turnover rate. Promotions and retention have to be performance based otherwise you would just have 20 year E-3s.

I wonder if author came across the 1988 Classic, "SPIT SHINE SYNDROME- ORGANIZATIONAL IRRATIONALITY IN THE AMERICAN FIELD ARMY"

The points of concern as well as recommended remedies are perhaps unsurprisingly similar. In the post Gold Water Nichols Era, as well as a slew of other legal and statutory requirements implementing such a system would be onerous. Additionally, not all locations (i.e. Divisions) are created equal much of the feedback identified through the efforts of AEMO and Army Talent Management Task force relate to quality of life and opportunities for families and spouses / partners. However, the author is prescient in driving home the need to change our evolution, promotion and retention approaches.

Well, not everything has to go. We can still have a centralized PME for officers and enlisted, as well as outside inspections by IG to ensure toxic environments and stagnation don’t develop.

And you can principally offer people a choice. After X number of years of service, give the officer and enlisted a choice of staying or moving to a different location. This would require units to actually make their locations worth staying in.

A good read and you have provided many points to consider regarding retention and its impact on recruiting. The Army faced a recruiting problem coming out of 2004 and 2005. They implemented the best recruiting incentive that completely turned 2 years of not meeting recruiting goals around in 18 months yet no one wants to talk about it. Incentivize referral bonuses work but the Army is scared to discuss the topic. The Army doesn't have a recruiting problem…it has a problem with its pride and arrogance. The Army has a solution that worked in 2006-2011 and worked in 1973 when they started it with the birth of the AVF.

Great Article.

I'm not 100% sold on the solution given our movement to the "mega" bases over the last 30 years, and a need to spread the good and less good locations around. Not doing so will just move the increased attrition to certain units.

General Eisenhower would have been shocked by todays personnel system. He wanted one that provided for the elimination of the unqualified. Our current one usually does succeed in eliminated the unqualified, but it also is forced to remove a good share of the qualified as well, and the different in OER record between the person at the bottom of the top third of the OML and the top of the bottom third is maybe one MQ.

As a Platoon Sergeant, I spend more time in a classroom going over Gender Identity and other politically based briefings than I do with my Soldiers being out in the field honing their chosen MOS skills. When I do exit interviews with Soldiers who are ETS-ing, the one thing they mention more than anything is the wasted training time on mandatory briefings. Military today is more concentrated on not offending individuals, instead of building cohesion.

Most enlisted Army recruits for basic training are single. I have 31 years of Army experience, so how about you?

That said, your statement about uprooting their spouse and children after basic is not true. Also, most Army wives choose not to work over getting a college diploma. Then wives freely choose to raise their children.

The Army has dumb the standards down to the point recruits would be a safety risk in training if taken any lower. Public schools are graduating recruits with lower standards now. My Grandfather's WWII unit had over 50% college grads or Soldiers that were drafted out of colleges to win our freedoms.

Today everything is given too high school grads like free college without earning a GI Bill or free Healthcare without working or paying taxes.

Perhaps you should center your articles on solid facts instead persuading people the Army doesn't know how to recruit.

One of the better articles I have read on the retention problem. I think you touch on some of the fixes. The division structure built amazing teams that were ready for war in the early 2000s. The Army should end the grinding late nights and absurd workaholic hours that they celebrate. It destroys people and drives them out. Excellent article.

If you want the best, you have to rack and stack them and not everyone gets to make it to the next rank. Interesting on all that article no mention of politics and political incompetence. When parents of children that have a variety of options watch 13 Marines killed because we didn't want to use the previous Presidents plan so we move the retreat and evacuation to a much more dangerous place, do you think we will tell our children great idea, join the Army. When a service member goes to prison for intentionally or unintentionally mishandling classified information but a politician who has boxes of classified documents covering the last 20 to 40 years with notes on how we collect the information and sources and is not even tried, are parents with children who have options going to say join the military. The college reimbursement is not nearly as big of a benefit when student loan "debt" is forgiven. And then there is telling people who liked President Trump that they are extremists and political personnel telling Soldiers they are terrorists for kicking in doors. Those that have options and don't have to join are putting aside their sense of duty because they are being judged and belittled for it. There are three options. Draft. Greatly increase salaries. Change the political culture.

Has anyone bothered to do a study on the impact of "wokeness"on recruiting? I know several retired soldiers, who have discouraged the kids, and grandkids from serving. We are losing some of our best recruits, and just imagine if we had to resort to a draft! Just imagine the mental issues many the these kids today would have. Gone are the days when especially young men gladly served and grew up hunting. We are in big trouble!

Exactly!!!!!

Sadly you’re missing the key issue. The DoD went woke without considering the impact on recruitment. When leadership adopted such an extreme political and social stance, they alienated 50% of the country. And that group is filled with multi-generation soldiers. My sons would have been the fourth generation to serve in uniform. After seeing what has become of the service, they have zero interest. And I can’t blame them. Marines haven’t had as much of the same issue as other services because they (mostly) haven’t forgotten the goal is to make warriors, not activists. And recruits can tell.

Major Rose.

I value the article you wrote. You've done your homework well.

I was an Army Recruiter in the South from 1974 to 1981. We, the Atlanta District, were number one in recruiting for the entire US. Now that has changed, as you stated, a better economy. Which has given potential recruits more options that did not exist in the 70's and 80's.

You're correct in the value of predictability for many Families. To up-rooted will increase separation of the Spouse and Husband. Or if your quits her good job. A household that's hard for a Solider to come home too.

Of course, no one at the "nose bleed level" will take action. Only until their is "Crisis."

A job well done. This should mandatory reading for the Joint Chief of Staff.

Dennis Crenshaw

MSG(E8) Retired

U.S. Army

"I would join the military but I object.to thier outdated personnel management model," said no 18 year old kid on the street, ever.

You can make that case when referring to retention, but it is absolutely absurd to suggest it has anything to do with the recruiting crisis.

To explain the current recruiting crisis you need look no further than comments by the president and chairmannof.the joint chiefs about "white rage," "white privilege," and "white supremacy ." No sane kid is going to join just be marginalized for something he has no control over. Of course, if you honestly mention any of that, you will be the next West Point grad that doesn't make his twenty years.

Great article. I spent 24 years in the Marine Corps, and we had the same issues.

A great and well thought out presentation. The exact same problems of recruiting and retention are horribly present in our nation's law enforcement agencies today.

California peace officer training and standards conducted a survey in 1990 that conclusively established the best recruiting tool was the currently serving police offer or sheriff deputy. We are only going to be successful at recruiting and retention. when we realize the untapped potential of treating our people with true respect for their well being.

Perfect thought. As a cohort unit from 1986. We did oset basic an AIT with the same soldiers, same Drill instructors and the majority went to the 101st either 327 or 502 brigade.

We were a team and I dare say a family. We learned from each other and the units had high Ranking experienced NCOs that led us.

Over time individuals selected to move on their owne (example LERPS) (delta, SF) and to other battalions when promoted to sargent.

To difficult to lead the troops you grew up with (E-1–E-4)

The mental of soldiers was strengthen by commoradity as we worked, lived, and played together.

I retired in 2006.

Someone should go back to the COhort days and look at the %that stayed in. Back then one set of orders had everyones name, so easy task.

I agree. I enlisted in 1983 and was in an Armor OSUT cycle. My Basic Training platoon was also a package platoon, meaning the entire platoon of trainees went to the same BN. We were broken up to fill vacancies within the 3 line companies, but we at least knew someone in the other companies from the get-to. Additionally, the company I was assigned to was a COHORT CO. The entire CO went through Basic together, then 18 months in 4ID, then 18 months in Germany. At the completion of the 3 year period those Soldiers who decided to remain in the Army were spread throughout the BN to fill vacancies and a new COHORT CO arrived.

Similar to what was discussed in the essay, the Army was attempting a Regimental System where NCOs had a "home" BN. They would serve in the BN, go off to another assignment (recruiting, Drill, school instructor, etc) and then be reassigned within the BN. The purpose was to have familiarity amongst Soldiers as well as unit location.

Final comment related to "up or out". During this same time frame in the early 80's Soldiers who wanted to remain in the service but were precluded due to either lack of rank or disciplinary issues could appear before a retention board. Chaired by CSM and 1SGs. The board had the authority to overrides or out" and allow Soldiers to reenlist. This removed the centralized board issue and allowed senior NCO's with personal knowledge of the Soldier to make reenlist decisions.

Robert G. Rose, great piece, and it echoes what I have been writing, speaking and pushing hard since 1997. I have not quit the fight, just branched off to other issues, such as developing people for Mission Command and Maneuver Warfare. But personnel reform must be the first place we begin. The personnel system and its policies are the foundation for the culture. I am sure you cited a ton of my work as what you wrote is what I have been saying for the last two decades. Please keep it up. Our Army and military could be so much better if we got rid of the Industrial-age personnel system. Good luck and pray for success in your career. They came after me a few times, particularly when I was on the cover of Army Times and in the Washington Post in June and September of 2002.

The Marine Corps made 109% of their recruiting goal. Perhaps there is a lesson here?

Thank you for this insightful paper

To add, if the Army values people they must hold toxic leaders accountable for their toxicity. Strategically, toxicity hurts retention. We can’t maintain talented individuals. They take their talents somewhere else.

The army and all service branches can help solve the recruiting problem by focusing on retention.

I agree entirely with the author. My experience working with National guard is a case in point. Guard units have facilities have become considered and disconnected from local communities. Which seems to reduce interest in and pride in guard units.

I also experienced the effects of up or out system. As a OCS commissioned officer. My class graduated in 1967. I was the only officer in my class to make to the rank of major and eventually retire. The majority victims of the RIF. Not for sub par performance, but lack of college degree, lack of quality assignments, lake of command assignments, assignments to other than commissioned branch. We filled a need for Vietnam and then were discarded..

Outstanding read! These topics resonate with me as an AG Officer from a personal and professional perspective.

The “move up or get out” culture is devastating for talent management at all levels. It degrades the ranks below SFC and MAJ level to just time-based achievements with little to no substance required to achieve the promotion. Mandatory List Integrations, automatic promotion to Corporal, mandatory attendance to Primary Military Education all take away from personal drive, motivation, and prestige as the Army will just force you through their career pipeline, assuming you stick around long enough to see it. Most people have a skill ceiling in any profession and that is OK. Why do we force people to leave the Army when that person could be a fantastic Squad Leader or Company Commander with no desire or capability to move past their current rank or station?

The idea of a Divisional System is appealing, assuming we still give Soldiers the autonomy and avenues to leave said Division in the name of career progression or personal desire. If the Marketplaces and movement cycles we currently have become a voluntary and opt in only process, we essentially create a “USA Jobs” situation for Soldiers. If I wanted to stay at Ft. Sill or Ft. Johnson for many years, why shouldn’t I be able to? I believe this idea will only work if the Amry demolishes the “move up or get out” mentality.

Stagnation is a legitimate concern in any organization, military or not. If talent management and careers are to be taken seriously, we need stop promoting low performers; eventually those individuals will see themselves out for lack of progression, or Army leaders with pride in their careers will bar them from continued service, refuse to re-enlist the Soldier, or start providing pink slips to Officers without a remaining service obligation.

The Army’s evaluation system needs to be re-worked. As someone that is heavily involved with movement cycles, evaluation management, and promotions I can tell you that our current system is counterproductive to honest and transparent feedback and often creates false motivation or purpose in our work force.

Outstanding read! These topics resonate with me as an Adjutant General Officer from a personal and professional perspective.

The “move up or get out” culture is devastating for talent management at all levels. It degrades the ranks below SFC and MAJ level to just time-based achievements with little to no substance required to achieve the promotion. Mandatory List Integration, automatic promotion to corporal, mandatory attendance to Primary Military Education all take away from personal drive, motivation, and prestige as the Army will just force you through their career pipeline, assuming you stick around long enough to see it. Most people have a skill ceiling in any profession, and that is OK. Why do we force people to leave the Army when that person could be a fantastic Squad Leader or Company Commander with no desire or capability to move past their current rank or station?

The idea of a Divisional System is appealing, assuming we still give Soldiers the autonomy and avenues to leave said Division in the name of career progression or personal desire. If the Marketplaces and movement cycles we currently have become a voluntary and opt-in only process, we essentially create a “USA Jobs” situation for Soldiers. If I wanted to stay at Ft. Sill or Ft. Johnson for many years, why shouldn’t I be able to? I believe this idea will only work if the Army demolishes the “move up or get out” mentality.

Stagnation is a legitimate concern in any organization, military or not. If talent management and careers are to be taken seriously, we need to stop promoting low performers; eventually, those individuals will see themselves out for lack of progression, or Army leaders with pride in their careers will bar them from continued service, refuse to re-enlist the Soldier, or start providing pink slips to Officers without a remaining service obligation.

The Army’s evaluation system needs to be reworked. As someone heavily involved with movement cycles, evaluation management, and promotions, I can tell you that our current system is counterproductive to honest and transparent feedback and often creates false motivation or purpose in our workforce.

We need all the ideas we can get on solving the recruiting crisis, but this isn't the solution. The Army is already "over-retaining" soldiers to make up for recruiting shortfalls. The Army has a pyramid force structure, with requirements for large numbers of junior soldiers to fill squads and teams. The model depends on a significant number of junior people leaving the force when their obligation is complete. When the Army "over-retains" it distorts the force and the Army becomes top-heavy with senior people, leaving junior positions vacant. This force costs much more to field and it also ignores the reality that modern combat is a "young-person's" game. The Army is already seeing the effects of this with squads and platoons in divisions being "zeroed out" due to the lack of junior soldiers.

You’re not getting it. To get people in the door they need a reason to stay. Yes, juniors are needed, but any person with a brain would rather push people out because you’re at capacity than working your ass off pulling people in – and failing at it!

Think of a nightclub. Do you want to be a promoter prowling the streets for low quality “talent” or being the hottest club in town with a line down the street having your choice of who gets in. Metaphor being both at recruitment and retention.

"A good product sells itself…The Army must ask why it needs to churn through so many recruits. And, it needs to learn a good product sells itself. An Army that soldiers want to stay in will be an Army that society wants to join."

Let people do the jobs they joined for. Let them have choice and agency in their careers. We preach to new 2LTs, "you are responsible for managing your career; no one is making sure you stay on track," but then we heavily discourage if not outright prevent them from pursuing the things that light their fires. I practically had to arm wrestle my brigade commander to get him to endorse a request to go to pursue an opportunity to serve as a technical expert at the schoolhouse so that I could do what I'm passionate about (help grow young Officers into tactically proficient Warriors), all the while he told me I'd be ruining "my" career doing a task that was beneath my potential. Instead, he wanted me to serve a general's aide, a job that holds not merely zero but actually negative appeal to me. If we can trust an officer to command with wisdom and consideration, we can also trust them to chart and steer their own career path with similarly sound judgment.

As a senior captain, I have no desire to go to ILE. In fact, the requirement to go to ILE makes me want to *get out* of the Army. Let me defer or avoid ILE for as long as I can capably serve in positions that tangibly contribute to the good of the Force; I fully accept and acknowledge the implications for future promotions. But two [more] moves in <12 months is too steep of a cost on my family when there are still ways I can make an impact without ILE. Similarly, I have a good friend who is an exceptionally competent, highly accomplished officer currently wrapping up his second command. And yet the Army is forcing him to go him to the Captains Career Course as his next assignment. To "learn how to be an effective company grade officer." That's asinine. Senior raters should be empowered to assess their officers and waive professional military education requirements for stand-out talent officers. Why waste the Army's time and money and a year of this officer's potential to acquaint him with concepts he's already mastered?

If the Army wants the benefits of talent management, it needs to let the talent do some self-managing.

I found the article interesting, and reflective of some issues I faced as an Enlisted Soldier of 1975 to 2001. The turnover, or would churning over be more apt, of unit personnel in 18 month or 3 year cycles does nothing to instill comradeship and esprit de corps within individual replacements. You needed time to grow into your assignment and develop skills, just to rotate out as you began growing into the position.

Couple that with changing requirements from DA on which boxes need to get checked off and when for promotions. The Army Reserve Unit I retired out of probably lost more long term soldiers due to abrupt policy changes coupled with civilian employment conflicts due to mobilizations. I wouldn't change my Army Reserve Career, it was challenging and rewarding. But the centralized promotion and impersonal box not checked, aspect did encourage me to put in retirement paper work.

As for the Army Educational System… enjoy that morass. It doesn't help enlisted retention either. Perhaps if the Army developed a Community College Program Such as the Airforce did, with the US MILITARY ACADEMY being the accredited overseer of course work and conferring institution of degrees would be helpful as well.

Please. Army doesn't care about their recruiting and retention goals. Every chain of demand and NCO abort channel I had to suffer through consistently promoted and tried to retain the soldiers who had multiple Article 15s and were trying REALLY HARD to get out while soldiers and leaders like me were doing well, staying out of trouble, making the promotion list, and proactively trying to stay in the Army were being kicked out. They had it backwards then and they hadn't really changed it now. Maybe they should start waiving people with felony records again. It helped them get their numbers up when I enlisted.

Bring back the draft these young people do not have any respect. Bring back the draft would help bring the crime rate down when in front of the judge give the person two choices jail or the military.

Great article. I am an Air Force brat my father served 25yrs, he was pushed out in 92. That same year I joined the Army, I watched as they offered NCO's bonuses to retire early, this was during the military down sizing in the 90's. After leaving the Army I find it hard to connect with those who didn't serve, I have struggled with holding jobs.Those of us who were born into military and have served are outsiders and don't fit in regular society. Our families move around the country and the word, we have different life experiences then those who don't serve, they maintain childhood and family relationships.

Why has it never been talked about? Military families are a tight community we tend to gravitate to each other when we meet in regular society because we have the same life experiences. Why don't they allow us to retire and stay where we're stationed? Instead of forcing us out into communities we don't share the same life experiences? Not saying that one group is better than the other just pointing out a fact. We know that most military child follow in the parents footsteps staying in the family business and the child will do the same.There wouldn't be a struggle for recruits, suicides would possibly go down because service members would be in the community they relate to. I feel the civilian side of society is chaotic and we Veterans are used as pawns for political gain. I have come across many who don't believe veterans deserve appreciation for their, I have personally been told we chose to serve no one made us join we're not special for our choice.

Again great article

While much of what the author wrote may be true, none of it is the reason why the military is in such a dire recruiting situation. Contrast, for example, the Air Force, Army, and Navy's recruitment problems with those of the Marine Corps.

In the former, recruits are nothing more than peasants … in the latter, you're part of the family, and you always will be.

Wow! Great article. My wife and I read this weekend, and it touched on many of the things that we have discussed since both of us had served in the Navy. We both left well before the 20 year retirement, but we have many friends still in, and I work for the Dept. of the Navy training Officers to Navigate, and drive ships. I don't always understand the acronyms and nuances of many who have obviously served in the Army branch, but I sense from some that they think this article, and the authors ideas, are not always the correct approach to fix recruiting or just plain wishful thinking. Some commentators were simply just frustrated and offer one offs because of their disgust with the "System" that they experienced in their careers. I feel the article is a great starting point for those who believe that not just the Army, but the services as a whole must change. Swap out Army with any other service, and you have many of the same issues outlined in the article. Move up or out is killing the Navy, and I have Lieutenants, Captains to the Army, who are leaving because they just want to navigate instead of punching tickets in jobs they don't want in order to advance. I felt so strongly about this article, I printed several off and gave to many of the active duty Officers to read. I gave one to my section boss and the CO of the school who just made a star. The services are a bureaucracy, and change takes time as you all know. Eventually, although probably dragged kicking and screaming, the services will figure this out. Many of the ideas profred by Major Rose will certainly be addressed and adopted, and in turn it will enable the US Army, and military at large, to be the best in the world. Thank you Major Rose.

I am glad to see this piece garnering considerable attention and spurring vigorous professional discussion in alignment with GEN George’s Fall 2023 request for renewed dialogue via MWI and other publications.

That said, I see several unexamined implications of these proposals if implemented.

First, a further pivot towards a long-service professional force will accelerate the US Army’s diminished strategic manpower depth. The “churn” decried by author can be more accurately characterized as “pre-trained military manpower” which is absolutely essential for LSCO and attritional warfare. The echoes of the pre-1915 British Army are eerily instructive here. We can have the most exquisitely trained standing force with exceptional small-unit cohesion, but that is utterly irrelevant if it is too small to survive and function after the first or second battle.

Fewer enlistees that serve longer, further starves our vitally important Individual Ready Reserve (IRR) pool which currently stands at fewer than 76,000 Soldiers – of all grades and specialties. By contrast, the Army IRR was 759,000 strong in 1973 and had about 450,000 Soldiers in 1994. Our IRR is in a parlous state and the cultural expectation of long-service as the norm will further deplete our strategic bench of available manpower for casualty replacement, unit fillers, and mobilization expansion cadre. The “churn” of soldiers that honorably complete their contractual service is actually healthy and a strategic insurance policy for the unknown.

The IRR serves as the Army’s “thin green line” between a very bad day and the availability of the first trained personnel inducted through the Selective Service System – if the domestic political conditions even allowed for its reactivation. The Army’s HRC estimates it would take about 277 days (M+277) for the first trained, entry level inductees to reach the operational force. Until then, the IRR is on the spot to “weather the storm” and it has far fewer personnel than many realize.

Second, the expectation of longer service at camps, posts, and stations located far from major population centers will further cement the Army’s isolation from society and hasten its path to irrelevancy for most Americans. The 1920s and 1930s were not a pleasant time for the Army due to this dynamic which was compounded by the societal sense of disappointment and anomie following the searing experience of WWI. We should be attuned here to the shadow that GWOT casts among many who served and among the general population. The Army can plausibly find itself in a far worse spot when it comes to popular support and legitimacy in a crisis if it follows these prescriptions.

Finally, this incessant push towards “personalized” and “bespoke” career management creates a highly fragile and brittle system that cannot withstand an extended LSCO scenario. Ukraine should be instructive on this point, but it appears that many in the Army are learning other lessons. In the Bakhmut sector alone, it was reported that Ukraine had elements of more than 30 brigades committed in early 2023. Combat at such a scope and scale characterized by disproportionate leader casualties is incompatible for exquisitely tailored personnel management for anyone but the most senior leaders. In fights with dozens of brigades present, even field grade officers can become commodities.

Many of the “industrial age” mobilization and personnel systems which are pilloried by some of today’s Army thought leaders are actually “lessons learned” from WWII. In fact, many of these lessons were learned at a very high cost in lives. We dismantled much of this infrastructure in the exuberance of the 1990s and the nearsighted strategic posture of the GWOT. The myopia of some of those decisions is now apparent and we should carefully assess the long-term implications of further decisions that will make America’s Army a smaller, less resilient, and further isolated force.

The IRR is a thin green line made of tissue paper, born from the belief that we could push previously-trained replacements into the field with a little refresher training. As tested since WWII, this hasn't worked tremendously well for troops beyond their first year after separation.

There is no requirement for IRR members of any service to meet any standards for readiness or training competency, and the services don't even do a very good job of keeping track of them. The Army, at least, is aware of those issues — I uncovered War College papers written on the subject in 1992 and 2013, as well as a history from the Army Reserve itself. Ultimately, the answer to effective employment of the Reserve Component is to do away with the concept of the no-cost body pool-in-waiting and require all reservists to train to some standard.

"…camps, posts, and stations located far from major population centers…." Are there such things in the today's CONUS? Threaten to shut down the smallest military installation, and legions stand up to show how many civilians depend on it for economic livelyhood. I can think of few CONUS bases with absolutely nothing around them, and none at all more than a 90-minute drive from a major town or city.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. It appears the Army has no "legacy memory" because the Army has made these same mistakes over and over and over again. Oh well, it's not my problem anymore.

If you treat your employees as if they're replaceable garbage, they don't want to remain your employees!

Wow, it's about time the military understands that as a core principle of managing large groups of people.

Might I suggest they start by putting body cameras on recruiters then reviewing the footage to verify whether or not the recruiter is outright lying to potential recruits in order to get them to sign up?