Get the people right, and the rest follows. So says General James McConville, the US Army’s chief of staff (effectively, the Army’s CEO), who also served as its G-1 (essentially it’s chief of human resources) for several years. Given this, perhaps it’s unsurprising that the Army is continuing a push to transform its human resource practices.

The effort began over a decade ago, when Army leaders realized that the service’s HR approach was increasingly misaligned with its organizational strategy and not really delivering the goods. The problem? Process-focused “personnel management,” developed for a conscript army in the Cold War era, simply wasn’t adept at competing for talent in the twenty-first-century job market.

Even more concerning was that Army HR processes often treated people as interchangeable parts rather than as uniquely talented individuals, with negative implications not just for organizational performance but for workforce engagement and retention as well.

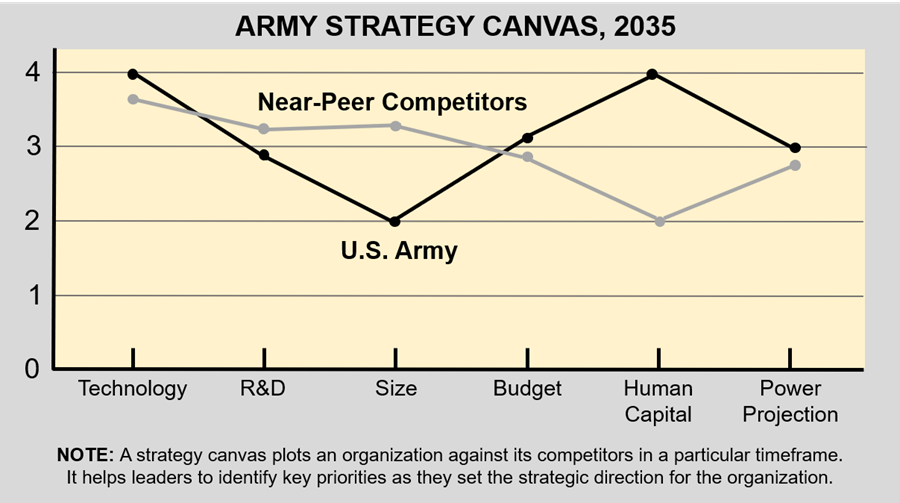

Simultaneously, near-peer competitors were both increasing their military spending and chipping away at the US Army’s long-held military technological ascendancy. Plotting these strategic trends made one thing abundantly clear: if superbly managed, the Army’s almost 1.4 million soldiers and civilians could provide its most reliable source of enduring competitive advantage.

Indeed, in the human capital era, no other resource drives—or constrains—productivity to the extent that an organization’s people do. As a result, in 2010 the Army began to reimagine its people practices. It’s certainly not the only enterprise to undertake the effort.

The State of HR Today

To maximize their people advantages, in the last thirty years many organizations have made HR central to the design and delivery of their corporate strategies. As HR’s focus has shifted from delivering efficient personnel services to increasing organizational effectiveness, the field has become quite specialized and differentiated.

Once preoccupied with administrative tasks such as strength reporting and payroll, today’s cutting-edge HR departments possess interdisciplinary expertise in several areas. These include strategic planning, organizational research, culture, talent management, learning and development, performance management, people analytics, labor economics, workforce planning, diversity and inclusion, total rewards, employee relations, risk management, and succession planning, to name a few.

These expertise areas also demand a variety of supporting skills, to include negotiation and relationship management, conflict resolution, communications, program evaluation, and coaching/counseling.

Transforming Army HR: Progress and Challenges

The Army’s pivot from transactional, compliance-focused personnel management to transformational, productivity-enhancing talent management has been consequential and successful. We’ve both participated in this evolution—one of us as an enterprise HR leader, the other as an HR researcher and strategist—and we can report that real progress has been made.

Today’s Army people practices are decidedly more effective than they were just a few years ago. More HR-specific organizational research, new talent assessments and improved leader selection processes, enhanced marketing and recruiting practices, and talent-focused job markets are all helping to improve Army talent alignment, workforce productivity, and organizational performance. Additionally, a new human resource information system called IPPS-A is helping to create the data-rich HR environment needed to support a robust people analytics capability.

Despite these successes, however, we share two concerns about the Army’s HR transformation that might sound familiar to executive management and HR professionals alike:

- First, the service’s people practices have improved too slowly. In a “VUCA” world—volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous—Army HR efforts must become much nimbler in order to sustain and increase the competitive advantage provided by its people.

- Second, the Army faces the persistent challenge of sexual harassment and assault, as well as growing concerns over racism and domestic extremism in its ranks. These challenges are receiving intense public, media, and congressional scrutiny. If not addressed, they’re likely to undermine national confidence in the Army while simultaneously reducing trust, cohesion, and readiness across its formations.

Assessing Strategic HR Needs

The impact of these thorny issues is Army-wide in scope, and certainly not the sole responsibility of its HR function. They do, however, highlight strategic HR needs in several key areas, such as rapid innovation; people analytics; diversity, equity, and inclusion; employee relations; and perhaps most importantly, organizational culture assessment and change.

As Chris Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal wrote in their seminal work on the HR function, today’s leaders are often “trying to implement third-generation strategies through second-generation organizations with first-generation management.” This is an apt description of the Army’s HR challenges, which exist in part because it has reimagined its HR practices without simultaneously reassessing its HR capabilities.

In fact, from a design standpoint Army HR is largely unchanged from two decades ago, even though its dedicated professionals are being asked to do different and more complex work in support of completely new organizational and human resource strategies. Additionally, Army HR’s occupational culture remains quite administratively focused.

We believe, however, that the Army can successfully continue its HR transformation by blending proven organization design and organization development principles. If it does so, the benefits should be dramatic. It’s an approach we’d recommend to any improvement-minded organization, HR or otherwise.

Blending Organization Design and Development

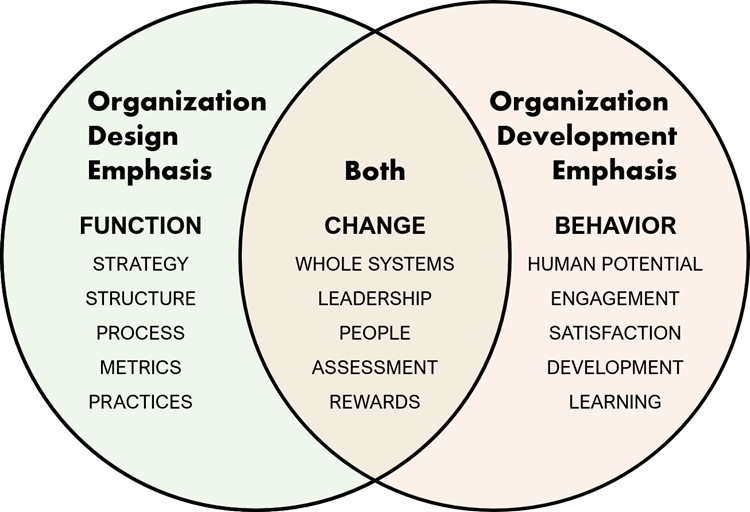

While sound organization design and purposeful organization development are both critical to organizational success, people sometimes confuse the two. After all, both disciplines seek to increase total organizational effectiveness. Practically speaking, however, organization design addresses how leaders want an organization to function, whereas organization development focuses on how they want their organization to behave to support its functioning—in other words, its culture.

What is Organization Design (ODS)?

Organization design focuses on how to get organizations to function in the way needed to achieve organizational goals and objectives. It starts with a current-state assessment that includes a review of strategic priorities, current organization documentation, customer and stakeholder feedback, and an analysis of challenges and opportunities.

What is Organization Development (ODV)?

Organization development is a planned process that employs behavioral and organizational theories and principles to affect change. Unlike change management, organization development is concerned with the whole organization system. In other words, organization development is focused not just on gaining competitive advantage, but also on enhancing human potential, development, and participation.

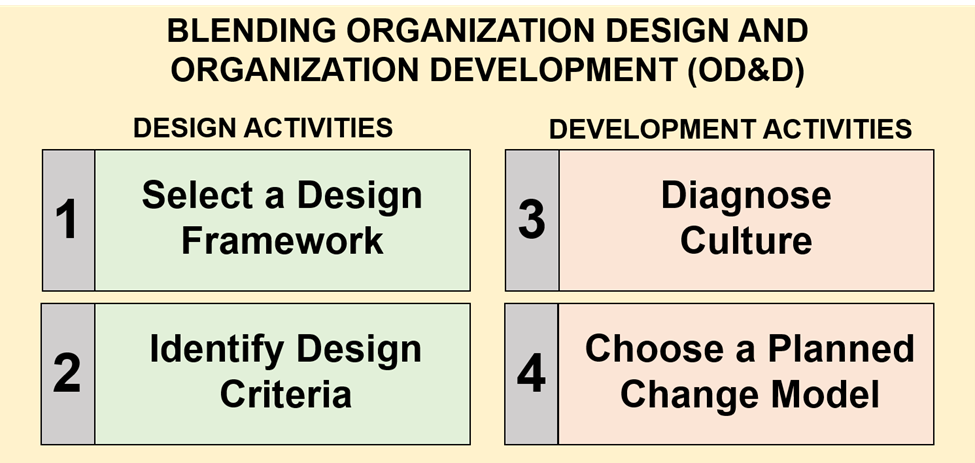

In our view, failing to blend organization design and development (OD&D) is like trying to row across a lake with one oar—you’ll get the boat moving, but you’re more likely to travel in circles than to reach the far shore. That’s why we’ve identified four key OD&D activities to help frame the Army’s strategic HR improvement efforts. While these are by no means the only steps needed to implement whole-system change, we think they’re particularly relevant to the Army’s current HR challenges and opportunities.

1. Select a Design Framework

While there are a variety of organization design frameworks in the management literature, Jay Galbraith’s “Star Model” is a good fit to Army HR’s organizational context. The model identifies five factors that must be carefully aligned to create an effectively functioning organization: strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and people.

A sound organization design begins with a strategy—strategies provide the criteria that all other design decisions are based upon. Organization design also addresses:

- Structure: How is power allocated across the hierarchy? What are the key roles? What’s the architecture?

- Process: What are the workflows? What are the coordination mechanisms? How are decisions made?

- Metrics and rewards: How do we measure organizational and individual success? How do we incentivize it?

- People practices: What talents do our people need to execute our strategy? How do we attract them, develop them, employ them, and retain them?

2. Identify Design Criteria

The Army recently published its first-ever People Strategy, which identifies several strategic HR capabilities critical to achieving its goals. These expertise requirements provide a sound basis for crafting Army HR’s “design criteria”—a clear expression of the capabilities needed to drive strategy execution. Design criteria should be:

- Specific, meaning they are measurable and not overly broad

- Differentiating, so they set the organization apart from competitors

- Actionable, so should start with a verb

- Future oriented and aspirational

- Capability focused, not just activity focused

Per the People Strategy, Army HR’s design criteria should position it as the domain of innovative human capital futurists—performance engineers, marketers and talent scouts, counselors and coaches, trend forecasters, technology integrators, organizational researchers, and perhaps most importantly given the Army’s current challenges, culture architects.

3. Diagnose Culture

The extent to which an enterprise-level HR function develops a strategic role and capabilities is deeply connected to its parent organization’s overarching culture. For many companies, giving HR such a pivotal role represents a tremendous break with the past, when HR was far more process and compliance focused. This was true for the Army as it embarked upon its HR improvement effort a decade ago, and it remains true today. It’s fairly unsurprising—members of large, mature, and successful organizations are more likely to assume that their long-held values and practices are the correct ones. In fact, “active inertia”—the tendency to cling to established practices despite dramatic shifts in environment or strategy—is a common organization development challenge.

What is Organizational Culture?

Organizational culture is the underlying values, beliefs, and behaviors that drive an organization’s social environment, and it plays a vital role in mission accomplishment. More simply, it’s how people within an organization behave on the job. Culture must change constantly to remain in alignment with an organization’s strategy—no organization should have the same culture it did a generation ago. The question for leaders is not whether culture should change, but how it should change.

To date, the Army has approached its HR transformation as a set of disparate change-management initiatives rather than as an HR-wide organization development effort. While several HR policies and practices have been modified to good effect, they haven’t been accompanied by an enlargement of Army HR’s strategic role, a change in its operating model and structure, or significant investment in its workforce.

The Army’s HR community shares some responsibility for this. Its occupational culture remains deeply rooted in the past, a time when HR was largely process focused and operationally oriented rather than people and future focused.

The Army’s overarching culture has also contributed to this state of affairs. While many of its leaders value the expression of differing opinions and perspectives, from the standpoint of collective-level dynamics the Army is not pluralistic. It features the top-down, control-oriented management often found in mature, hierarchical organizations.

Control-oriented cultures tend to operate from the premise that the most senior leaders “know best about matters of strategic importance and need unilateral control over such matters.” These cultures also tend to believe that “unity, agreement, and consensus are signs of organizational health, whereas dissent and disagreement must be avoided.”

This type of workplace culture often breeds “organizational silence”—an unwillingness on the part of employees to challenge status quo approaches or propose new ones. Understanding this can help the Army to select the right change model to build its strategic HR capabilities.

4. Choose a Planned Change Model

The odds of successfully implementing the type of whole-system change we’re describing go up dramatically when organizations employ a planned change model. A variety of choices exist.

For example, one is Kurt Lewin’s three-phased “Unfreeze – Change – Refreeze” framework. Another is the classic eight-phase Action Research Model, which recognizes the more dynamic nature of the contemporary operating environment and relies upon the creation of new knowledge to continuously change and improve an organization.

A third model, and one that we believe to be a good fit for the Army’s culture and context, is the Positive Model, which employs a process known as Appreciative Inquiry (AI). Rather than being deficit focused, AI identifies those things the organization is doing right and builds off them to increase its capabilities. It also promotes much broader involvement in the change effort, and it uses aspirational images of the future to motivate positive action.

Evidence shows that a positive, strengths-based approach to change makes people and organizations more resilient, builds greater connections between coworkers, and enhances creativity and innovation. As we’ve said, the Army has already made genuine strides in its efforts to improve its HR information systems and practices, and its People Strategy provides a positive, optimistic vision of its future HR capabilities. Amplifying these initial successes can both sustain and accelerate Army HR’s transformation into a value-creating, strategically capable function.

An old Japanese proverb states that “vision without action is a daydream, while action without vision is a nightmare.” In the Army’s case, it began transforming its HR practices without also undertaking a comprehensive HR organization design effort. The resultant “nightmare” was a gap between what Army HR can do and what it needs to do, making the Army less nimble in response to strategic opportunities and challenges.

The good news is that the Army has jump-started its HR organization design effort by creating a comprehensive HR strategy. As that effort unfolds, however, a companion organization development effort will be needed, one that shifts the Army’s human resources culture from transactional to transformational and makes smart human capital investments in its HR professionals, who are committed to taking on a larger strategic role.

The Army’s most senior leaders will have to collaborate with and support their HR workforce in the creation of a strategic HR capability, one that can truly put “people first.” The blended organization design and development framework we’ve described here can help them to do so.

We believe the time to act is now, and the payoff will be worth the effort. Instead of “awaiting resolution of the thorny questions and then implementing the requested HR programs and practices,” a transformed Army HR function will lead the discovery and delivery of new innovations, ensuring that the Army’s people remain its most enduring source of competitive advantage.

Dr. Mike Colarusso (Ed.D., MSHRM) is a researcher in the Office of Economic and Manpower Analysis at West Point and a coauthor of both the Army People Strategy and Senior Officer Talent Management: Fostering Institutional Adaptability (US Army War College Press).

Major General Douglas Stitt is a career Adjutant General (Human Resources) professional with over thirty years of experience and is currently the US Army’s Director of Military Personnel Management at the Pentagon.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Capt. Matthew Pargett, US Army