The 2020s have kicked off with a plethora of strategic challenges. Alliances are under strain and the promise of liberal institutionalism is fracturing. Brexit has finally occurred and now Serbia is taking issue with the broken promises of the EU. The United States seems, to many international observers, to be exiting stage-left from global leadership, while Beijing has exposed its own structural challenges, which might ultimately prevent China from taking the reins. Also, populism is back with a vengeance.

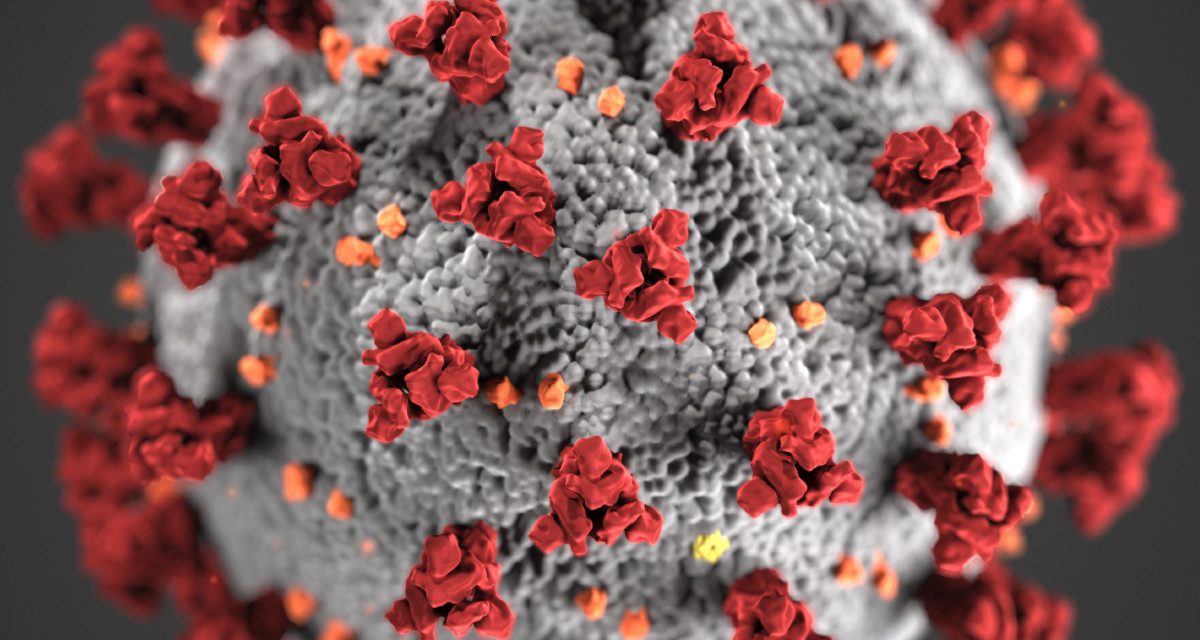

Not to mention the litany of deglobalization hot takes. Nor should we overlook the global oil price crash that began earlier in March. For now, COVID-19 leads this pack of security challenges. But much of the focus remains on the economic consequences of the pandemic. International attention is fixed on the security of supply chains, global transportation, and financial markets. But what about the geopolitical and strategic questions, specifically about multidimensional impact of the pandemic on the international system?

This is a question for the millennials. After all, the consequences are likely to be felt for years to come. These are questions about their future security.

Millennials—those born roughly from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s—are now “adulting.” Sure, some of us are home bingeing Netflix in lockdowns across the globe. Others are stepping into security policy positions within governments, taking part in intellectual debates within strategic studies circles, and some of us are starting to teach the next generation of security scholars, practitioners, and policymakers. This requires a fundamental discussion of who we are and how our values, interests, and life experiences have shaped our worldview and security outlook.

Our contemporary strategic environment is increasingly contested, competitive, and chaotic. Truth be told, this is all the millennial generation really knows and we face down the 2020s largely desensitized to the world around us. The generation has had a formative development in the global security sphere. Those born in the 1980s remember watching 9/11 in classrooms and then later trying to make sense of it at home. Those born well into the 1990s join their Generation-Z younger siblings in having no living memory of the attacks, simply born into our forever wars in the Middle East.

Communication technology advanced in lockstep with a contentious global environment. Millennials grew up with the internet boom and early on we swapped CD-ROM encyclopedias for the world of Google. The inundation of opinions and the 24-hour news cycle served to normalize the contested and challenging world around us. But it also made us passive observers to international-security developments.

At university we studied security affairs in real-time and with the advent of WikiLeaks had access firsthand to policy discussions. We learned about the primacy of international law and the utility of international-relations theory while watching as Russia redrew European sovereign borders for the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, concepts of the West and the “rest,” as well as terms like “liberal democracy” and “globalization” shaped our worldview.

Globalization created—in its very basic form—intricate bonds of interconnectivity across the globe. Western millennials have largely benefited from the processes of globalization but at the same time, have done very little to protect and strengthen the system we have enjoyed. We left this task to the generation before us.

Deglobalization might yet be the ultimate fallout of COVID-19. We can expect more borders to close, states to turn inward to protect their markets, and populist leaders to double down on efforts to solidify their power bases. Of course, the degree of deglobalization isn’t preordained, but it is a safe bet that the post-pandemic world will look different than before in meaningful but as-yet-unpredictable ways. The 2020s might be marked by a “new” Great Depression. The downturn in the Chinese economy specifically could force it to turn inward, although there are signs that Beijing also sees in the crisis an opportunity to enhance its global-leadership credentials. Likewise, we are yet to see how India responds to the COVID-19 challenge and this will determine the trajectory Delhi takes in terms of becoming a multipolar power, which ultimately impacts the future makeup of our international order. These are the wildcards waiting to be revealed.

The coming few years will demand more of the millennial generations, and the first requirement will be for the group to rediscover (or create) a sense of agency in international affairs. The 2020s will continue to throw up transnational security challenges that, as COVID-19 is illustrating, millennials will be unable to switch off from or opt out of. An obvious place to focus our collective efforts is mitigating the security impacts of climate change.

The global pandemic will likely hasten the end of Washington’s unipolar moment, bolstered by continued navel gazing and domestic political distractions. Perhaps some cause for optimism is that the current security challenge is unveiling the new multipolar international system—a system in which more is required from Europe and in which middle powers like Australia will exert growing influence. Millennials ought to capitalize on this as an opportunity and start thinking about the world we want and not the world we have watched or grown accustomed to.

There will be some tough lessons in the coming years. Millennials moving into more senior policy and military-security roles will be taking over from a generation that has spent thirty years working in a unipolar strategic environment, albeit one that has been slowly eroding for much of that time. Millennials growing influence in their new roles will come against a backdrop of change—including that toward a multipolar international system. We must accept, even embrace, that new reality, and learn to leverage it as the best shot we (collectively) have at securing a future history in which the promises of globalization might really be delivered. The onus is now on the millennial generation to be prepared to respond to security challenges—and increasingly to lead those responses—ensuring that we don’t allow ourselves to remain desensitized by the unprecedented complexity that has characterized our experience of the international system for most of our lives.

Millennials will also have the opportunity to lead the debate in considering the future of our international system—both in terms of relationships between states and of the overall system’s capacity to cope with security challenges that have multidimensional consequences. The geopolitical consequences of COVID-19 are likely to include an inward populist turn for many states and the splintering of traditional alliances. This potentially leads to the end of the “West versus the rest” approach to international security. The pandemic will hasten the pace of reconfiguration of our international system. While some await a plague of locusts and the four horsemen of the apocalypse to arrive, millennials should consider their agency in the international-security environment. And be ready, when the time comes, to do something with it.

Dr. Elizabeth Buchanan is a Lecturer in Strategic Studies for the Defence and Strategic Studies Course at the Australian War College in Canberra and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Modern War Institute at West Point. She specializes in Arctic and Antarctic geopolitics as well as Russian foreign energy strategy. She holds a PhD in Russian Arctic strategy under Vladimir Putin and was recently a Visiting Maritime Fellow at the NATO Defense College. Dr Buchanan’s book on Russian Arctic strategy is forthcoming with the Brookings Institution Press. She is a proud millennial.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

I am not sure its is about deglobalization but about reshaping strutted supply chains as well as another key trend which is how manufacturing is changing to allow for proximate supply chains. And I would argue that the difference between the liberal democracies and the 21st century authoritarians will be accentuated by this crisis. That said, I already think the nature of alliances has changed from 2014 on in that they provide broad frameworks but nations are pursuing coalitions of the willing built around specific areas of collaborative agreement. For example, the only European states that are pursuing the Russians with counter cyber attacks are France, the UK, Sweden, Finland, and Estonia — the rest of the EU and NATO except for the US is sitting it out.