Editor’s note: This is the latest article in “Rethinking Civ-Mil,” a series that endeavors to present expert commentary on diverse issues surrounding civil-military relations in the United States. Read all articles in the series here.

Special thanks to MWI’s research director, Dr. Max Margulies, and MWI research fellow Dr. Carrie A. Lee for their work as series editors.

In 1786, Benjamin Rush, a Founding Father of the United States, described a “partial insanity” gripping American soldiers. A politician, physician, and former surgeon general of the Continental Army, Rush diagnosed American “military mania” as individuals’ overuse of military technical language and disregard of history. He wrote that “it is impossible to understand a conversation with these gentlemen without the help of a military dictionary.” Centuries later, despite Rush’s diagnosis and subsequent legislation, writing guidance, training, and doctrine, the language of the United States military still requires its own dictionary.

The US Army has long recognized the need to document its technical language for outsiders. US soldiers have privately compiled and published dictionaries since 1810, acknowledging that without these lexicons, military language is incomprehensible to both civilians and other members of the military. The first official US military dictionary was published in 1944, documenting thousands of official Army terms, abbreviations, and acronyms that had unique importance within the Army and little utility outside of it. Military jargon has been confounding since the founding, raising the questions: Why did the Army develop such a unique lexicon? And what are the effects of a distinct military-specific language on civil-military relations?

Jargon is often described as deleterious to communication, which is only partially true. Jargon is extremely useful within technical communities as it speeds and eases communication. However, to outsiders, jargon encodes technical information and creates information asymmetries. Beyond communication, the language boundary between the military services and civilian oversight has broader material, symbolic, and organizational implications. Jargon can be used intentionally to signal knowledge of a topic or obedience to a higher authority. Furthermore, its connection to funding and prioritization enables organizations to strategically apply language as a survival strategy. These functions beyond communication allow us to better understand civil-military translation and the purpose, power, and longevity of military jargon.

The Development of Mil-Speak

Military jargon did not begin in, nor is it unique to, the United States. This is made clear by French “soudardant” from the 1500s, the quadrilingual Lexicon Tetraglotton’s military terms of “warr and soldiery” of 1660, and the many historical military manuals from across the globe. Today, the US military is infamous for its labyrinthine vocabulary and profusion of terminology and acronyms impenetrable to the uninitiated. Rosa Brooks described learning to “speak DoD” as requiring a “total-immersion language course.”

Unique functional dialects are common in communities of practice, defined as “aggregate(s) of people who come together around mutual engagement in an endeavor.” Medical professionals, “tech bros,” academics, lawyers, and countless other fields have developed jargon, jokes, legends, and other systems of meaning unique to their mutual endeavor. National security is a shared endeavor, but the professional experiences of civilians and uniformed military often differs—those experiences initiating individuals into related but different communities of practice.

Military language is not monolithic—there is no uniform mil-speak. Air Force jargon is not the same as Army jargon, which is not interchangeable with Marine Corps or Navy terms. Furthermore, the joint dialect has been described as a totally different language from that of the Army. Not only does each service have a unique style and dialect, but occupational specialties within the services have their own dialects. A history professor at West Point (47K) likely does not share jargon with an astronaut (40C) or a bandmaster (420C). Even within the Army, jargon is extremely fragmented.

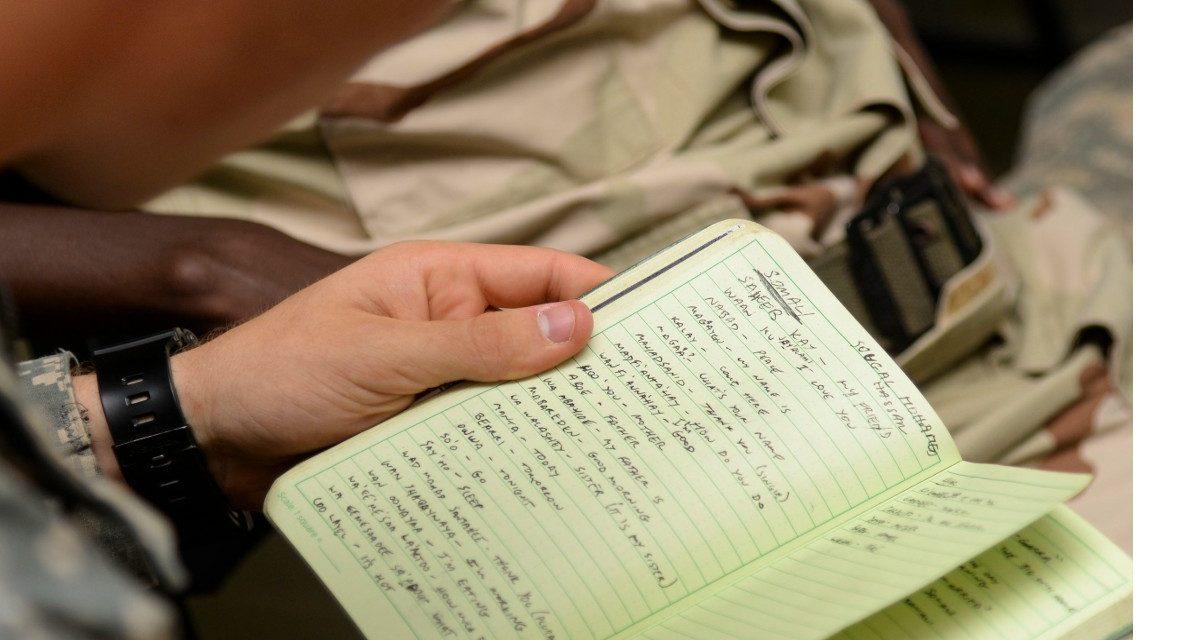

Because jargon is tied to functions rather than individuals, individuals move between these communities, learning the appropriate jargon for each function as they progress through a career. The result is multilingual soldiers, familiar with the jargon of each functional role that they have occupied. Importantly, non-uniformed employees of the services learn jargon in the same way. Department of the Army civilian employees with no uniformed experience speak functional fragments of the Army dialect.

Encoding Information and Linguistic Distancing

The military’s deep technical knowledge about capabilities, activities, doctrine, and more creates an information asymmetry that can complicate civilian control and oversight. Jargon enables this asymmetry. First, jargon encodes military technical information, masking information from outsiders until translation occurs. Second, jargon distances and conceals certain military functions from the principals.

Technical jargon encodes the activities of the military in the unique dialect codified in hundreds of dictionaries, strategies, and doctrine publications. Capstone doctrine for the armed forces clearly states that doctrine “provides a military organization with a common philosophy, a common language, a common purpose, and a unity of effort.” These reference documents create a uniquely military system of meaning that requires training to access. In some cases, jargon puts a technical veneer over an object that requires no technical expertise. Temporary duty assignments (TDY) are work trips, personally owned vehicles (POV) are cars, personnel manning documents (PMD) are rosters.

By setting the military apart and allowing technical language to flourish, the “alchemy of linguistic distancing” renders certain activities less visible. The most commonly cited examples of this abstraction is language for the act of killing, such as “neutralizing targets.” The accidental death of civilians during attacks on military targets are referred to as “collateral damage” or even more obliquely as “CIVCAS”—an abbreviation of civilian casualties. The term “lethality” was officially codified in doctrine in October 2022 as meaning “capability and capacity to destroy”—not the typical standard English understanding of capacity to cause death. Through language, the emotional and physical experience of war is obscured by the snappy specialized terminology of technical processes.

Civilians untrained in navigating the web of military reference documents are at a disadvantage when attempting to conduct oversight responsibilities. Further complicating communication, organizations like Congress have technical information masked by their own jargon. Jargon can be used to mask and distance activities intentionally. However, more often mistranslation is a case of individuals with limited time and resources, struggling to fully translate their own jargon, inadvertently undermining the transparency that they seek to create.

Signaling Authority and Obedience

The existence of a language boundary also creates opportunities for signaling. Often as signals, the words themselves become more important than their meaning. The ability to use technical terminology appropriately requires experience or training and thus jargon can become a proxy for that experience. Excessive technical language can bamboozle listeners into a false perception of expertise. One study found that the more difficult a written work is to understand, the more likely it is to be seen as important and prestigious. Problematically, one can learn to use jargon appropriately without fully understanding what it means.

Jargon adoption also signals obedience to oversight or individuals at higher levels of the organization’s hierarchy. Key terms introduced in the National Security Strategy will appear in the National Defense Strategy and National Military Strategy. Integrated deterrence was introduced in the 2022 National Security Strategy, despite the twenty-seven types of deterrence already in existence. The term immediately began to cascade down the hierarchy of strategic documents, including the 2022 National Defense Strategy and other strategic messaging. These cascading usage effects are often less about the term’s meaning than they are about enacting power relationships.

Buzzwords or introduced jargon are not always used because individuals believe in the explanatory value of the terms lethality or integrated deterrence. Rather, organizations display the buzzword to show deference to leadership and avoid decreased funding or support. Buzzwords may lack explanatory value but they carry the weight of relevance and the focus of leadership. This creates a serious risk for oversight, as it is challenging to differentiate true organizational change from cosmetic relabeling that simply parrots the desired words.

Strategic Priorities and Organizational Survival

Language choices allow agents to activate the material functions of jargon. Jargon is a bureaucratic tool for moving resources within an organization. Jargon adoption allows organizations to avoid losing their funding when their function is deprioritized. For example, the 2018 National Defense Strategy focused on “joint lethality in contested environments,” calling for department restructuring if current design “hinder[s] substantial increases in lethality.” This engendered several incidents of creative jargon usage.

In June 2018, the Pentagon held a briefing series titled “Showcasing Lethality.” One of the missions highlighted in this series was the Hawaii National Guard’s response to erupting volcanoes. When asked to talk about the “lethality component” of volcano response, the briefer described how the work illustrated the “dual purpose” of the National Guard, serving as “real world training that is a force enabler to folks down range that are absolutely tied to the warfight.” Volcano response has little to do with “the warfight” or joint lethality. However, the 2018 National Defense Strategy contained a clear directive to “consolidate, eliminate, or restructure” organizations that did not support lethality. Logically, in response to this existential threat, the Hawaii National Guard had to justify how one of its core activities supported a critical strategic priority.

National strategy shapes dozens of subordinate documents and tends to be highly abstract. Abstractness creates space for organizations to place their efforts under the umbrella of different strategic priorities. It is critical to note that there is not necessarily conscious evasion or malevolence in these bucketing processes. People believe in the importance of their organizations and their work. In the face of overt statements that unmatched activities will be restructured or canceled, language matching becomes a survival strategy. Strategies can only list so many priorities and, inevitably, some military functions are left out. Oversight bodies must recognize the constraints that their language creates, while also looking beyond the labels to assess programs.

Learning to Decode

Historically, attempts to improve intramilitary and civil-military communication have focused on restricting jargon use. In 1910, the Army’s Field Service Regulations included its first writing guidance, outlining the importance of clarity, decisiveness, and brevity. Through the 1990s, Field Manual (FM) 101-5, Staff Organization and Operations simply stated: “Do not use jargon.” The Army has had some success in shrinking doctrinal terminology. Today, there is one-eighth the number of official terms than existed in 1944. As for the joint community, the reverse is true. From 1948 until the early 2000s, codified jargon grew 700 percent. Addressing the quantity and functions of jargon is not only a linguistic question—it is a bureaucratic, legal, and structural one. But mitigating some effects of jargon on civil-military communication is possible.

First, as individuals, we must learn to recognize our own jargon. We do not “stand outside” of our areas of expertise or our topics of analysis. Every school, training, and work environment teaches us functional jargon. Identifying our own jargon is particularly challenging because cognitively, humans struggle to accurately identify personal background knowledge as not being universally known. If writing about any topic specific to your profession or on which you have received specific training, most words particular to that topic are likely jargon.

Once jargon is recognized, it can be translated for a different audience. Effective communication is not always about avoiding jargon, it can be about using the correct jargon. Today, the current FM 5-0, The Operations Process no longer advises officers to not use jargon in internal memoranda. Instead, it tells them to communicate “using doctrinally correct military terms and symbols.” When communicating within one’s community, use the approved jargon. In the regulations concerning correspondence, writers are told to not use military jargon in letters to people outside of the Department of Defense. Once jargon has been identified, it can be replaced with plain language or the jargon of the community for whom you are writing.

Lastly and most critically for civilian oversight, it is necessary to recognize the incentive structures that make language a signal or an organizational tool for survival. “Military mania” is less “partial insanity” than rational survival strategy. When lack of alignment with stated priorities risks an organization’s restructuring or defunding, clear communication becomes secondary to survival. Volcano response becomes an exercise in lethality.

Military jargon has existed for hundreds of years and will continue to persist. Jargon use is not a mark of failure, but a feature of the system of organizations, functions, and incentives that make up the constellation of US civilian and military organizations. Jargon opens a door to “the secret kingdom” of expertise and knowledge. Without knowledge of that technical language, the door remains tightly closed. We also must recognize that at times, what the word means is less important than what the word does. Only by applying all our available lenses—doctrine, funding, hierarchy, and many more—can we fully decode the mania.

Dr. Elena Wicker is a presidential management fellow at US Army Futures Command. She completed her PhD at Georgetown University and is a nonresident Fellow with the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare at Marine Corps University. Dr. Wicker researches the history of US military lexicography, the politics of military document drafting, and the bureaucratic power of jargon and terminology to shape innovation and modernization.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States military, the Department of Defense, or the US government.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Benjamin Raughton