Millennials can now storm the beaches of Normandy and fight Nazis with a new level of realism. Sure, past games like like Castle Wolfenstein let them role play America’s Greatest Generation. But the recently released Call of Duty: WWII provides a more human and realistic dimension of war, whereas previous videogames delved into fantasy or featured cyber-mutant soldiers out of a bad ’90s movie.

Will all this realism help future soldiers perform more effectively on the battlefield? To answer this question, a team of West Point researchers headed for the wooded hills that encircle the upstate New York campus, where every summer cadets must perform a series of challenges and exercises to demonstrate their leadership capabilities, ability to work in teams, and so forth, all while cut off from the outside world. It is a real attempt to replicate the conditions of war.

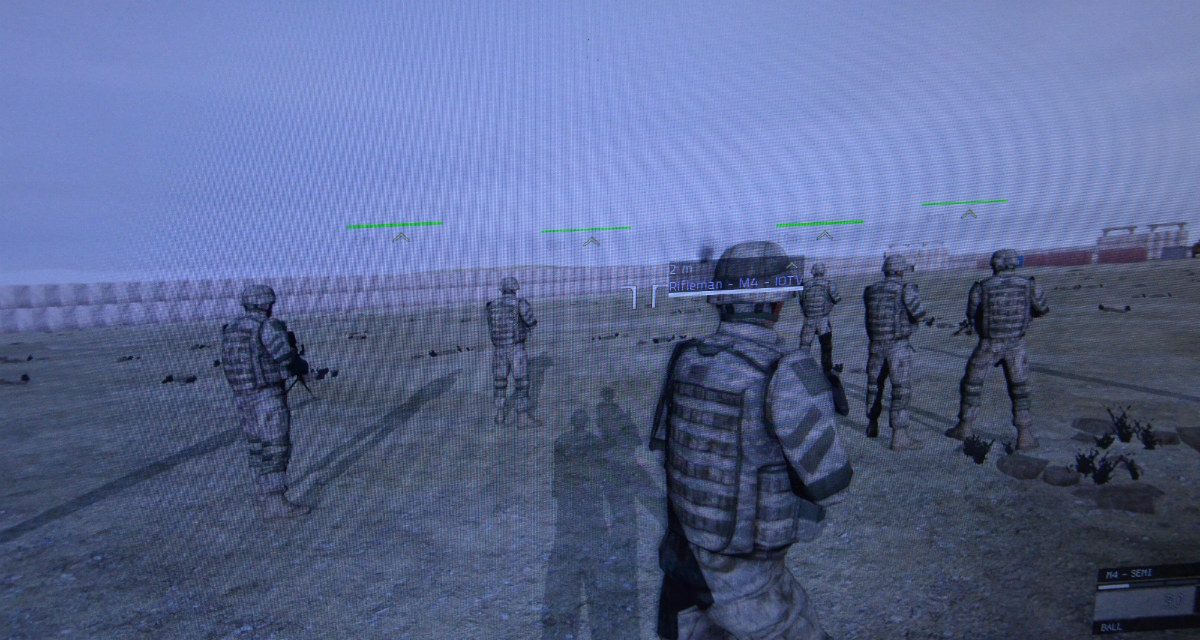

For one of the scenarios, cadets were tasked with conducting an urban raid mission on a clutch of abandoned buildings made to look like a town one might encounter in the Mekong Delta or Anbar Province. Half of the cadets were randomly furnished with a packet of high-definition photos of the target buildings; the other half were given virtual-reality goggles that provided 360-degree footage of the area, similar to Google Street View. One was analog and primitive, the other high-tech and provided near-perfect situational awareness of their surroundings. Guess which one cadets preferred?

Lionel Beehner is an assistant professor at the US Military Academy at West Point and director of research at the Modern War Institute. Maj. John Spencer is the deputy director of the Modern War Institute. He looks forward to connecting via Twitter @SpencerGuard. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US government.

Image credit: Master Sgt. Paul Wade, California National Guard

Don't mistake detailed visual realism for detailed functional realism. Any wargamer knows there are assumptions and compromises built into any model or simulation due to limits of the presenting platform, computational power, and desired "playability". Games built for entertainment are especially subject to this — no one would play COD if they only made it up the beach one out of every five tries.

Even tech-savvy youngsters — perhaps especially tech-savvy youngsters — are quick to discern when tech isn't useful to them, either. A packet of aerial photos may be old school, but lay them out correctly, and there's enough of a model to give someone a feel for the complete subject. Pipe Google Street View into your VR goggles, and you have a detailed view from a single spot. To get the same perspective as from the aerial photos, you'd have to "stand" in a number of different locations, and mentally stitch them together.