The Marine Corps’s approach to providing commanders decision-making tools at the tactical level requires a fundamental reconceptualization if it is to support effective decision-making on the twenty-first-century battlefield. The current proliferation of both commercial and government-developed sensor technologies combined with authoritative data sources across the joint force opens up the opportunity to develop critical decision-making applications at the point of need. To achieve this, the Marine Corps must develop a trained data workforce and behave as a software- and data-centric organization. A trained digital workforce can create a tectonic shift that negates ponderous bridge building across the digital chasm between the enterprise and tactical levels. However, this will require the Marine Corps to break its cycle of outdated information technology (IT) practices, create a trained cadre of digital professionals, and develop an ecosystem that can appropriately scale across the enterprise.

The Digital Development Cycle

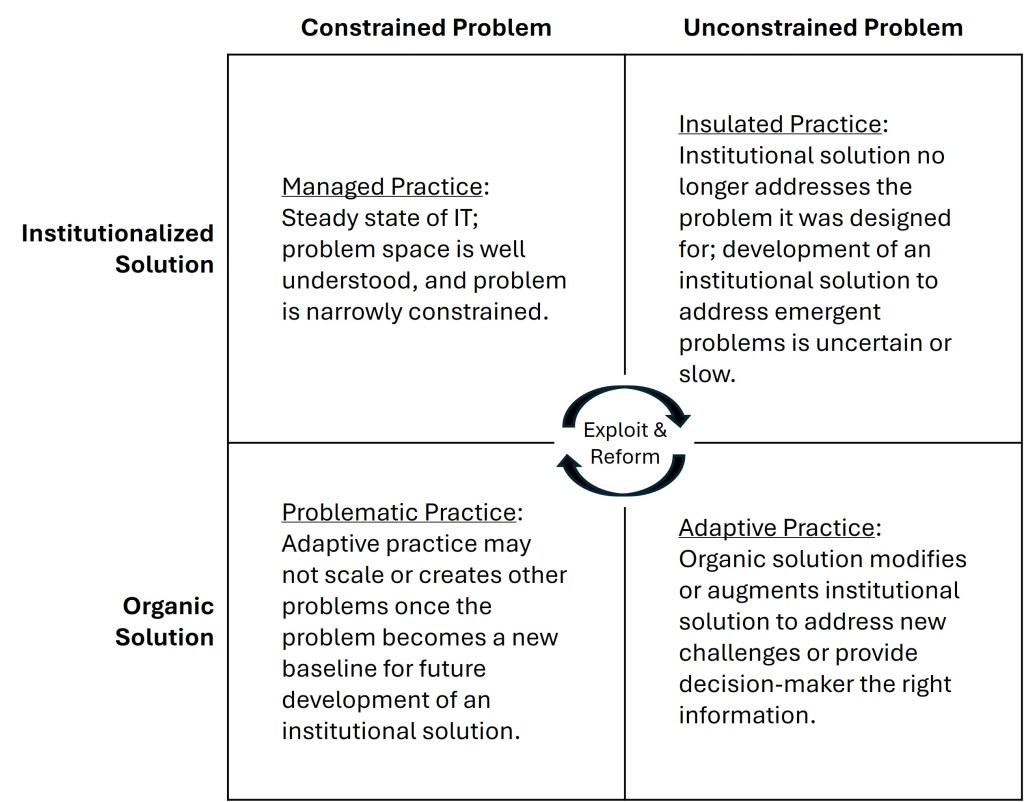

In his book, Information Technology and Military Power, Jon Lindsay demonstrates through four historical case studies how militaries experience a continuous cycle of IT development. Lindsay’s perspicacious work demonstrates the ebb-and-flow development cycles of military IT. These cycles, he explains, address both constrained and unconstrained problems with institutional or organic (tactical) solutions. Table 1 shows how this continuous cycle provides a useable framework for understanding how militaries develop IT solutions. Lindsay calls this a theory of information practice. However, the development of enterprise applications for tactical solutions is often far too slow to operate and respond in today’s rapidly evolving information environments. Moreover, expertise at the point of friction and the right suite of development tools now allow the democratization of solution development at the tactical level. These changes can therefore fundamentally obviate the cycle Lindsay has seen in the development of traditional military IT decision tools. Instead, the Marine Corps can better adapt to the constantly changing information environment by placing the preponderance of its digital and software development at the tactical level with an enterprise structure focused on support to tactical-level development.

Reforming the Cycle

Information is a key driver across all warfighting domains. This is becoming increasingly true as digital solutions with their concomitant data captured from military and commercial sensors create a need for not only greater amounts of storage and processing but analysis that informs decision-making. However, this results in resource decision dilemmas at multiple points within the Marine Corps. At the enterprise level, organizations responsible for concepts and capabilities development are in the business of projecting the kinds of future systems Marines will need to fulfill their assigned missions. This project deals with a host of counterfactuals and uncertainties for the kinds of applications, data, and interdependencies within a system of systems that may exist in the future. Lindsay’s framework helps to explicate a full-cycle example. At the tactical level, Marines deal with a variety of present systems often developed years in advance by the enterprise (managed practice). However, decision systems developed years in advance may not adequately address new requirements of the tactical-level commander (insulated practice). This can often drive personnel to develop, modify, or augment these systems to meet current requirements (adaptive practice). Yet, such tactically developed solutions may not scale well or may introduce cyber vulnerabilities (problematic practice). An institutional response for making modifications to this system may often require additional budgeting and acquisition efforts to yield an adequate solution (managed practice) sometime in the future. The Marine Corps, however, possesses all the capabilities necessary to break this perpetual cycle of poor IT practices.

The current suite of open-source and proprietary tools and the accompanying know-how available to develop solutions is both prodigious and available across the Marine Corps. For this reason, development of digital solutions for decision-making no longer needs to reside solely at the enterprise level. The tools for development at the point of need can dwell in a hybrid cloud or on a laptop for some instances. Rather than focus on architecting any stand-alone digital application, higher headquarters and capabilities development can work toward ensuring authoritative data from the joint force and commercial sources is made available to the tactical level by publishing APIs (application program interfaces), negotiating enterprise database access, and developing data pipelines that commanders can access. Then, development at the tactical level can focus on responding to the dynamic needs of the commander. Additionally, organizations such as the Marine Corps Software Factory and Marine Corps Tactical Systems Support Activity have the resident expertise to support and respond to the requirements of digital development. Properly resourced, these organizations can function as intermediate support activities that can help surge provisional capability and capacity to a unit as necessary. Organizations with the right technical focus are best positioned to exploit many opportunities to support a commander’s decision-making process. Therefore, pushing digital development below the enterprise level will allow it to be more responsive to a commander’s emergent requirement. Still, the Marine Corps must redesign its employment of technical talent to help achieve such objectives.

Point-of-Curation Developers

The challenge to sustaining tactically developed solutions hinges on having the correct personnel with the right kinds of skills. In fact, it is long past due having Marines with the technical skills to design digital solutions at the tactical level. Marines embedded across the Marine Air Ground Task Force (MAGTF) with skill sets that range from data curation and application development to data science can provide a hedge against the fluctuating dynamics of the modern battlefield while supporting data-fusion requirements for better decision-making. Moreover, these skilled Marines who are embedded in the various staff echelons are in the best position to understand a commander’s intent and decision-making processes. These same Marines also create important connective tissue to higher-level organizations because they understand that accurate data and information is necessary for organizational decision-making. Therefore, having Marines at the point of curation who implicitly understand the importance of data and information properties (i.e., conforming to DoD’s VAULTIS goals—data that is visible, accessible, understandable, linked, trustworthy, interoperable, and secure) are in the best position to ensure data passed to higher levels meets such standards. Moreover, the Marine Corps Artificial Intelligence Strategy requires leveraging these embedded experts who can communicate the right kinds of use cases that need higher-level support. This concept of embedded digital experts requires a dedicated occupational field, which would provide a structured career path for Marines with these critical technical skills. To realize this archetypal shift, the Marine Corps must have a professional cadre at the tactical level with robust enterprise and intermediate support.

A concept for digital professionals at the tactical level will likely sound obtuse to some military mavens. However, the projected denied, disrupted, intermittent, and limited environments of future battlefields will create uncertainty and will likely limit which data may be available to a tactical leader. Leaders in this situation may have to rely on only data they can acquire or generate locally. Having Marines who can develop solutions and provide analysis on the fly will increase in importance. For instance, these Marines could function similarly to the US Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps Data Warfare Company, which provides data-centric problem-solving and software development at the tactical level. Marines with similar skill sets as those in the Data Warfare Company, applied at the point of friction, also understand the nuances of their local data environments, commander’s intent, and organization’s culture. Such knowledge and flexibility will therefore allow the Marine Corps to adaptively respond to uncertainty on the future battlefield. Nevertheless, the Marine Corps must also ensure a scalable and interoperable ecosystem exists for these Marines to support tactical applications.

A Scalable Enterprise Ecosystem

The last piece needed to ensure the Marine Corps can maximize the benefit of having embedded experts is an ecosystem that promotes interoperability and scalability. Such an ecosystem, supported by a variety of development tools that range from business intelligence (e.g., Microsoft PowerBI, Tableau) to open-source tools (e.g., R, Anaconda), can provide a sufficient number of common platforms for development and displaying analysis for decision support. These and other development tools are already well proven and scalable. To support Marines at the tactical edge, the Marine Corps needs the ability to also develop applications on a common platform.

With development pushed down to the tactical level in the hands of capable Marines, the enterprise still needs to ensure developed solutions are scalable by establishing common digital interoperability standards. These standards ensure development can scale best-of-breed solutions that conform to a common baseline with security in mind. Development to a digital interoperability standard will also help prevent the codebase and subsequent development from incurring a variety of technical debt. To truly achieve digital interoperability, the Marine Corps requires a standard baseline across its various platforms to allow seamless development. At the tactical level, for instance, the Marine Air Ground Tablet (MAGTAB) with its associated MAGTF Agile Network Gateway Link and other supporting networking systems provides a robust and well-proven platform that also integrates Android Team Awareness Kit and Tactical Assault Kit plug-ins. This allows Marines to easily scale decision-support tools and situational-awareness applications across the MAGTF while sharing the same common operational picture. To support this radical change, the Marine Corps could divest from its other handheld offerings that currently do not scale and do not match the MAGTAB’s digital interoperability. To wit, MAGTAB currently provides a number of integrated planning and execution tools that are easily published to other devices in the network. Development on a platform such as MAGTAB will simplify the training pipelines for Marines while promoting the scalability necessary to truly achieve digital interoperability. Anything short of this both inhibits the MAGTF from effectively synchronizing important command-and-control products and decision-support aids while squandering limited development resources and time. The Marine Corps can ill afford additional software pathways by having experts developing in multiple different, unscalable environments. Such an arrangement inhibits cross-pollination across warfighting functions and reduces effectiveness.

Barriers to Adoption?

Any proposed solution will have a variety of challenges to resourcing and implementation. This particular proposal could suffer from at least two shortcomings resulting from resourcing and retention. First, projected DoD budgets are anticipated to remain flat for the near future. Therefore, resourcing such a proposal could cut into existing and future programs, which may not provide adequate funding to support such an initiative. Second, attracting, training, and ultimately retaining military personnel with technical abilities is already a difficulty experienced across the joint force. Additionally, meeting these resourcing and retention challenges comes with impacts across all DOTMLPF-P categories (doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy).

To address these shortcomings, the Marine Corps should first look to consolidate its digital handheld offerings into a single program of record to achieve both cost savings and economies of scale. By eliminating multiple contracts for other handhelds that currently lack true digital interoperability, the Marine Corps could reduce contract management and achieve significant savings while simultaneously consolidating development to a single, interoperable platform. Additionally, this opportunity could result in manpower savings, but these would need to be tracked as part of the resources recuperated from these initiatives.

Next, much of the technical talent already exists across the Marine Corps to accomplish this but is currently unevenly distributed. The talent called for in this proposal already exists in several military occupational specialties, including 06XX (communications), 2652 (intelligence data and software engineer), and 88XX (8846, computer scientist; 8848, data systems management officer; 8850, operations research analyst). To help with retention, the Marine Corps should target Marines across the force in their second enlistment or officers who desire to pursue a staff track as currently projected by Talent Management 2030. Offering advanced technical training with appropriate obligated service, additional incentive pay, opportunities to train with industry, and a meaningful mission would help retain such Marines.

Lastly, launching this initiative as a pilot program would help reduce lock-in risk and allow valuable lessons and feedback on growing these capabilities organically. Similar to the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab fielding cutting-edge technologies to get early fleet feedback, the Marine Corps needs an equally resourced human capital effort to support experimenting with small teams of trained digital developers. This approach can help avoid adaptation through guessing. While DOTMLPF-P considerations are normally conducted upfront, it may be more appropriate to work backward through supporting a flexible pilot program that evolves gradually to help tease out resourcing requirements rather than a traditional top-down approach. In short, Marine Corps leadership can create a true scalable and interoperable digital capability by overcoming these shortcomings through deeds rather than words and PowerPoint presentations.

On December 1, 1995, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff published Joint Vision 2010. The document was prescient in stressing the importance of information superiority even before the exponential explosion of data generated by the internet. Yet, by the time the services actually reached 2010, commanders were instead experiencing information overload. Arguably, one reason for this is that commanders did not have the requisite expertise, tools, and processes to manage all the data and information they had access to. Today’s commanders no longer must suffer from the scourge of information overload—if the right organizational structures are in place. By integrating these ideas with other emerging concepts such as the forthcoming digital operations concept of employment, the Marine Corps can create a holistic approach to digital transformation that addresses both the technical and organizational challenges facing the Marine Corps.

By breaking the cycle of outdated IT practices and fostering organizational structures for digital professionals to work in a scalable ecosystem, the Marine Corps can more efficiently and effectively support tactical commanders across all domains of the modern battlefield. Of course, given warfare’s inherent uncertainty and complexity, it is impossible to know precisely what we will need in the future, but having Marines with the right skill sets supported with the right tools will provide the adaptability the service needs.

Scott Humr, PhD, is an active duty lieutenant colonel in the United States Marine Corps. He currently serves as the deputy director for the Intelligent Robotics and Autonomous Systems office under the Capabilities Development Directorate in Quantico, Virginia.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

The author would like to thank Colonel Sean Hoewing, USMC, Lieutenant Colonel Charlie Bahk, USMC, and Captain Zachary Curran, USMC for their helpful edits, insights, and feedback.

Image credit: Cpl. Savannah Norris, US Marine Corps