On the day in 1967 when Hamilton Gregory reported to a Tennessee induction center to begin his service in the U.S. Army, a sergeant presented him to another young man who was also headed to Fort Benning, Georgia, to start basic training. The other new soldier’s name was Johnny Gupton, or so Gregory calls him. “I want you to take charge of Gupton,” the sergeant told Gregory. Before they boarded the bus to the airport, the sergeant handed Gregory Gupton’s paperwork along with his own, to carry on the trip.

In the next hours and days, Gregory discovered why the sergeant had put Gupton in his care. Gupton could not read or write. He didn’t know his home address or what state he was from, so he could not send the pre-stamped postcard the new recruits were given at Benning to tell their families they had arrived. He didn’t know his next of kin’s full name, didn’t know that there was a war in Vietnam, and couldn’t tie the laces on his combat boots.

How did a man so obviously unfit for service get drafted? A slipup? Far from it. Gupton was one of more than 350,000 other young men drafted during the Vietnam war under a deliberate policy requiring that nearly a third of all military recruits should be drawn from men with general aptitude test scores at the bottom or for a certain percentage below the minimum standard. This while draft boards around the country made it shockingly easy for middle class, better educated men to avoid serving — just ask Bill Clinton or Donald Trump or Rush Limbaugh. The policy was known as Project 100,000. Its principal promoter was Lyndon Johnson’s defense secretary, Robert McNamara.

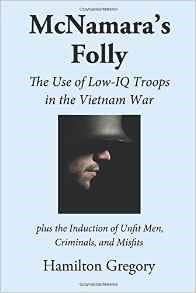

Hamilton Gregory — who was not drafted but enlisted voluntarily — was troubled and outraged by his experience with Johnny Gupton and subsequent encounters with other low-IQ draftees. During his Army service he raised questions about the policy with various superiors, and after his discharge, while making a career as a journalist and author, he kept on tracking down official documents and seeking out personal accounts. The evidence he accumulated over more than 40 years makes the story he tells in McNamara’s Folly not just convincing but ironclad. Its conclusion is ironclad too: U.S. draft policy during the Vietnam war was a moral atrocity.

Project 100,000 troops were killed or wounded in Vietnam at higher rates than in the U.S. force as a whole, but the unfairness didn’t stop there. More than half left the service with less than honorable discharges — not surprising, for men who weren’t mentally fit to be soldiers to begin with. Gregory notes the perversity: “An unsuitable man is taken into the military and then returned to society — with stigma — for being unsuitable.” Piling yet another disadvantage on already disadvantaged lives, those discharges deprived them of veterans benefits and further limited the already small chance that those men had to find any kind of stable job in civilian life. And for the same reasons they got drafted in the first place — that they were inarticulate, ignorant of the rules and their rights, and politically powerless — they were the least able to appeal those bad discharges. As Gregory observes, we eventually amnestied men who illegally evaded being drafted, but nobody lobbied for amnesty for McNamara’s bad-paper vets.

McNamara’s Folly is heartbreaking to read, but it tells a story that most Americans have never heard and that should be remembered far more widely than it is. It deserves the widest possible readership.

[Photo source: PatriotFiles.com]

Hamilton Gregory, McNamara’s Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War (Infinity Publishing, 2015)

Past was prologue to the morals waivers of the late 2000’s; see, e.g.,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/apr/21/usa1

http://www.usarec.army.mil/im/formpub/REC_PUBS/r601_56.pdf

And McNamara was rewarded with a permotion to president of the World Bank a bank who`s mission is to help the disadvantaged on the largest scale on the planet..Nuff said!

The World Bank is also where Paul Wolfowitz, one of W’s neo-conmen, wound up.

I served in the Infantry with many of these low IQ soldiers. It was very sad and so wrong.

McNamara’s perfidy knew no bounds. There is a report, then secret (1961) called the “Webb McNamara Report” that was the recommendation to the president to begin the Apollo race to the Moon. In that report the rational’s were not what we have been told in history, but were associated with keeping engineers from leaving large companies that were having a brain drain due to the beginnings of commercial space companies. Another reasons was that McNamara wanted to use the Apollo program as a marketing tool for the great society programs of the 1960’s. Those of us who are old enough to remember know the phrase “If we can put a man on the Moon, surely we can solve, X, Y, or Z social problem.

I had an RTO in Vietnam so inept that I couldn’t let him answer an incoming call. His instructions were to let it ring until he could find someone else to receive the message. This worked for our advisory team; I don’t know what would happen if we were a TO&E unit.

We had an RTO in the field with the 101st Airborne Div. He was the platoon leaders rto. The grass was so high and so thick my rifle team had to drop ruck sacks and machete a trail through the grass. the team leader and his rto would come forward and the rifle team would go back to get our rucks and the rest of the co. The rto was from Kentucky. He wore glasses with one lens cracked.Scared out of his mind. The Lt. would pull out a Combat leaders field guide and start reading it. It was very scary to move the co. forward with the rto that scared. Neither one of them should have been in the field.

I realized something like this must have gone on when I found out a boy in my school had served. I thought he was lying at first. He couldn't pass his classes. He got a certificate of attendance instead. I can't imagine him with a gun.I want to read this book soon.

Sad but true. However, a modicum of relief was grsnted by Discharge Review. Many ‘bad paper’ discharges were upgraded to General and even Honorable in the mid to late 70s by the Discharge Review Board of the Army.

In Basic Training, I was a “platoon guide” and learned from our company first sergeant that you could ID a Project 100,000 soldier by their serial numbers. Typical draftees of the period had numbers beginning with 51, 2 or 3, however, “McNamara’s boys” numbers began with their year of induction usually 67 or 68. The 1SG’s admonition; “Keep a close eye on ‘em.” An astonishing forty percent of that BCT company was recycled!

Later as a platoon leader in Vietnam, I inherited a guy whose ineptness was stunningly dangerous. Noting his being a Project guy, I immediately got him sent to the rear, to save his life, or someone else’s he was bound to have gotten killed, an action roundly applauded by my NCOs. These men had no business anywhere near a weapon, much less carrying one where others depended on competent, quick-witted actions. Robert McNamara has a lot of blood on his hands, Project 100,000 is yet one more part of it.

McNamara’s Folly is a surprising book. i was so surprised to know that Project 100,000 troops were killed or wounded in Vietnam at higher rates than in the U.S. force as a whole.

WOW!! I WAS IN ARMY RESERVES 1963 TO 67,AND NEVER HEARD OF THIS UNTIL TODAY!

I WAS NOT TREATED WELL IN THE ARMY DUE TO MY LIFE LONG KLUTZINESS WITH BALANCE AND SMOOTHNESS OF WALKING AND MARCHING!

THANK GOD HOWEVER I HAD THE MENTAL CAPACITY TO SURVIVE AND ENDED UP WITHOUT MY VIETNAM NAM "13MONTH HOLIDAY"

What the hell! I certainly distrusted Mac, I too served in Nam with combat men who did more harm then good. However, as a student of war history, history is wrought with dangerous men who never should have been enlisted much less an officer. as for Vietnam I regret I volunteered. The Army hamstrung the Marine Corps otherwise the Marines could have kicked ass and the NVA would have capitulated by 69.

Robert McNamara's main claim to fame when he became an original member of John F Kennedy's 'whiz' kids as they were called, was his previous employment with Ford Motor Company and was head of the development team of the Ford economy car the Falcon!

The wars, and thousands of men's fate, was then greatly determined by his advisory position to President Lyndon Johnson.

At least Richard Nixon put an end to it finally………..