Competition is older than warfare itself; it is the original politics. Whether you want to go biblical or prehistoric—competition is there. Arguably, Adam and Eve’s original sin was the result of a failure to realize they were not exempt from competition—something the snake took full advantage of. Likewise, our ancient ancestors, even before they discovered fire, were likely competing over food, shelter, and mates. So why talk about competition like it is something new? The answer is quite simple. Because our broad planning framework of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) does not adequately address the current state of competition within the geostrategic environment, and we are at risk of losing the gains made over the last century.

As I wrote in a previous article, Multi-Domain Battle offers a perspective on this challenge. However, it is not the first or only recent case to offer potential solutions along similar lines. Prior to Multi-Domain Battle, the joint concepts community began work on the Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning (JCIC). The JCIC is by far the most mature effort to change the paradigm for military campaign planning. If you want to debate Multi-Domain Battle, a good place to start is in comparing these two documents and how they use competition, how they define the security environment, and what their impact means for the US military and the government as a whole. Centrally, how do the JCIC and Multi-Domain Battle each represent competition and how will that change the way we plan, execute, and assess our efforts?

What is the JCIC?

The JCIC aims to address the current inadequacies of campaign planning—especially as it relates to competition. As highlighted in part two of this series, US military planning constructs stagnated as the operating environment evolved. Framing planning and policy discussions around phasing constructs serves as an inhibitor to application of military force in the present circumstances. To resolve this, the Joint Staff developed the now published JCIC.

Published in March 2018, the JCIC encapsulates the joint community’s efforts to understand and provide a framework for effectively campaigning in the emerging operational environment. The JCIC defines the current, ongoing, and future environment by identifying two distinct but related sets of challenges. The first is the contesting of norms by adversaries who employ creative strategies, below the threshold of US military response, which embrace ambiguity and seek to exploit vulnerabilities in how the US military is employed. Second, this environment will be defined by persistent disorder from instability spreading out from weak states, which increases the likelihood of wars involving at least one non-state actor and crises that evolve more rapidly.

The JCIC responds with a framework designed to change the way we think and plan against these challenges. While there is much in the JCIC that warrants discussion, the competition continuum is one of the most important takeaways.

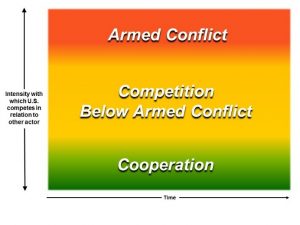

The competition continuum is represented by a spectrum going from cooperation, through competition below armed conflict, to armed conflict itself. As of publication of this article, a draft joint doctrine note on the JCIC defines cooperation as “a cooperative relationship between the United States and another strategic actor that can be general (as with a close ally) or limited to only a specific issue.” This definition implicitly makes an important point: cooperation is not limited to allies and partners, but can also include competitors and adversaries when interests align. In the context of the North Korea problem set, US cooperation with Japan and China provides an example of this notion.

In cooperation, policymakers can leverage national elements of power to engage selectively, maintain, and advance. Engaging selectively is transactional cooperation for the purpose of achieving a specific strategic objective; think of it as the United States engaging Iran on their nuclear program. Maintaining focuses on open-ended cooperation that sustains relationships and secures bilateral advantages without significant resource outlays, in the manner that the United States has sought to deepen ties with Ukraine to offset Russia-backed separatists chipping away at Ukraine’s sovereign borders. Finally, advancing provides open-ended cooperation within a close, enduring national commitment to an ally or partner. Examples of this include Afghanistan and NATO.

The next level above cooperation is competition below armed conflict—“a competitive relationship between the United Sates and another strategic actor on a specific issue in which the use of armed force is prohibited or severely restricted.” At this point along the continuum, policymakers have three possible options. US policy can seek to improve the overall US strategic position by employing all measures short of what may lead to armed conflict; with minimized risk, it can attempt to counter competitors’ actions to maintain a strategic position and prevent competitor gains; or, within policy or resource constraints, it can contest “with prudent means” against the adversary.

The final level of the continuum is armed conflict—“a competitive relationship between the United States and a strategic actor in which the Joint Force may employ armed force.” In armed conflict, the potential options include working to defeat an adversary by imposing desired US strategic objectives, deny and frustrate an adversary’s strategic objectives, or degrade the adversary’s ability and will.

The combination of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict is not new. However, this approach is a shift from the doctrine and mental models that have been used to shape policy discussions regarding the use of military power over the last two decades. Current doctrine, and even Multi-Domain Battle, refers to this as the conflict continuum. What the JCIC provides is not just new window dressing, but a new perspective. The JCIC views conflict as subordinate to and part of competition.

Until recently, despite more than a decade of counterinsurgency operations, the geopolitical consideration of utilizing military force was predicated on a process of escalation. You were either on a road to war or a road to peace. Why else would you be leveraging military force? What the JCIC posits is that the road we’ve been driving on is competition. We can head towards war, deterrence, or cooperation—but the portion of spectrum that represents peace is gone. For even with our closest allies, there will always be competition.

However, the model on which the JCIC is built has its limitations. Whereas the doctrinal conflict continuum is a relational causal pattern, as discussed in part two, the JCIC is best described as a mutual causality model. This model is based on two things impacting each other. The impact can be positive or negative for both, or positive for one and negative for the other. The causes and effects are often simultaneous, but can also be sequential, which means that this can be event-based or may be a relationship over time. In the context of mutual causality, the JCIC centers on competition, which is defined by the friction between cooperation and conflict activities (the two things impacting each other) over time.

We Have to Change If We Are Going to Compete

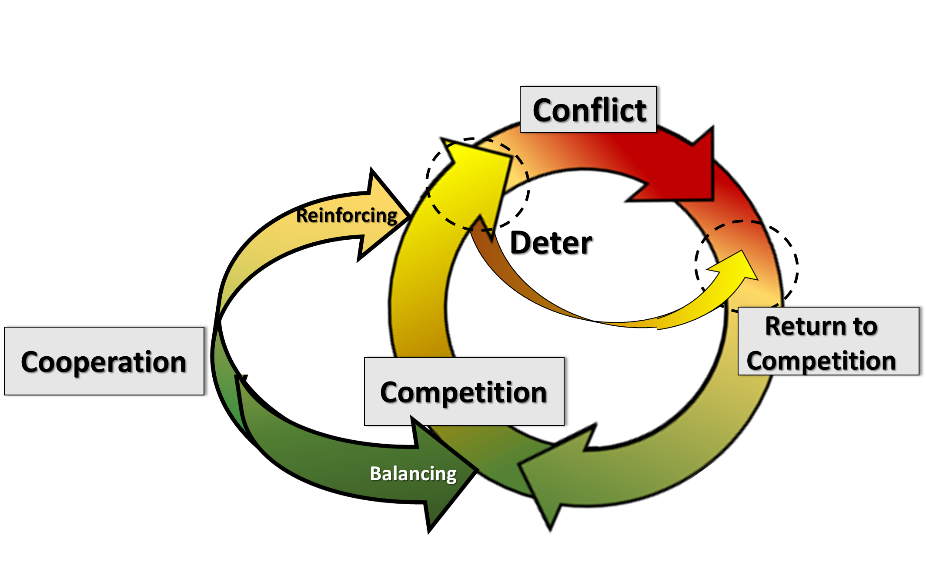

While the JCIC competition continuum provides a significant shift in mental models for how campaigns are visualized, there is still room to improve. Given the mutual causality model of the JCIC’s competition continuum, this construct enables strategists and planners to clearly identify where we are on the continuum in relation to a problem set and associated actors. That said, a mutual causality model can help you understand why things are the way they are, but lacks the ability to tell you what is to come and how you can organize and campaign towards desired ends. This is where the cyclic nature of Multi-Domain Battle’s conflict continuum comes into play, by providing the type of baseline required to successfully design effective campaigns.

To do this, however, the Multi-Domain Battle conflict continuum must learn and evolve. Multi-Domain Battle’s conceptualization of competition as a three-point cycle (competition, conflict, and return to competition) does not include the JCIC’s key element of cooperation. But fixing that is easy. In the context of Multi-Domain Battle’s conflict continuum as a cycle, cooperation can serve as a feedback loop that, depending how you employ it, either reinforces or balances the conflict continuum. By doing this, we can start to assess where we are going.

The elements of cooperation (advance, maintain, or engage selectively) and how they are applied determine the nature of the feedback loop. Advancing and maintaining cooperation would largely focus on partner nations. Engaging selectively occurs with other nations with whom we are either in direct competition or have limited shared interests, and with whom our other interests diverge. In context, advancing and maintaining cooperation activities reinforce the conflict continuum because those actions can increase deterrence and the ability to win in conflict, and are often perceived as being in direct competition with our adversaries. Selective cooperation, however, serves as a balancing feedback loop because it increases opportunities for communication, creating empathy, or developing additional shared interests.

While the Multi-Domain Battle concept does mention cooperation eight times, between the document and its annexes, it is always in terms of a reinforcing feedback loop—it is all about driving towards and winning in armed conflict. In the concept’s defense, this is exactly what it aims to do. But this leads to another concern: Multi-Domain Battle centers on a critical assumption regarding deterrence and escalation—that winning in competition requires the ability to win in conflict.

Traditional deterrence is largely dependent on the ability to shift the cost-benefit balance into one’s own favor. In terms of military power, then, the ability to dominate in armed conflict is the ultimate trump card. However, conventional deterrence hinges on escalation, with demonstration of capabilities coinciding with political will to use them. Herein lies the rub. Our current adversaries, North Korea arguably being the exception, know this and purposely design their efforts to make gains without provoking escalation. Which leads to a critical question: How do we win in competition if adversarial actions merely chip away below the threshold at which US policymakers are willing to authorize a direct military response?

While Multi-Domain Battle identifies future capabilities that will serve as a powerful deterrent through demonstrable overmatch on the battlefield (the subject of a future article in this series), demonstrating these capabilities will force policymakers to take action as means of escalation and direct application of military power—in other words, a show of force or other flexible deterrence options. Without a change in mental models, policymakers may not see the value in escalation, all of which leads to a considerable gap.

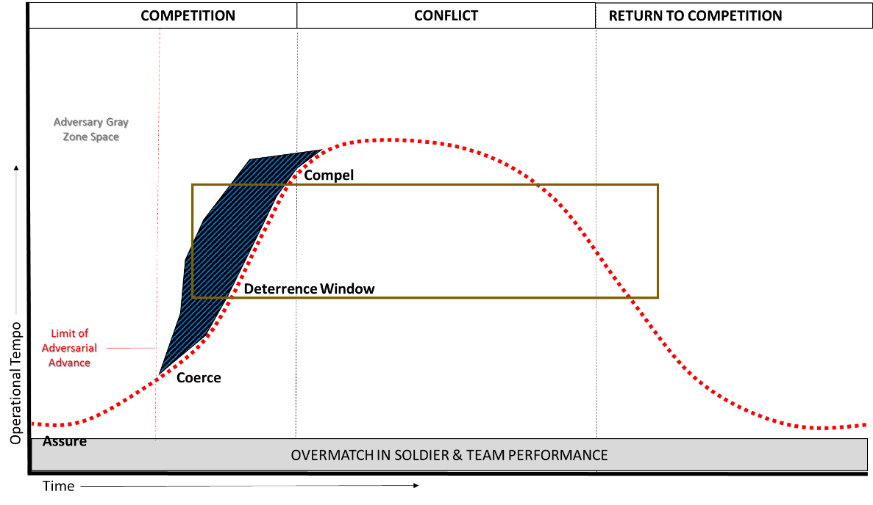

The problem, then, is our failure to effectively compete against adversarial actions and gains within the gray zone space. The US military excels when operational tempo is high, because we can drive the conflict continuum much more easily as we increase the pace by which we make and execute decisions through a synchronized effort, exceeding the capabilities of our adversaries. However, under our current idealistic models, we hamstring ourselves partly through failed mental models that inhibit increases in operational tempo. Whether it is either a perceived or a real lack of political will, time, and resources, or the fact that we are just not having the right conversation between planners, commanders, and policy makers, we need a change.

Multi-Domain Battle’s future force components provide a baseline to increase operational tempo in the competition period. This potential impact is highlighted by the shaded area in the figure above. Represented in this shaded area are the gains made by calibrating force posture, creating resilient formations, and converging capabilities in the time and place of our choosing. However, the future force components do not address the lower end of the spectrum of competition, where our adversaries have gained the most at the potential cost of our long-term national interests.

One possible solution to increasing our advantage with increased operational tempo is through cyber, space, electronic warfare, and mission command systems that compete where escalation is not politically viable. However, from a planning perspective, the key to winning in competition is changing the way in which we develop strategy, campaign plans, and contingency plans.

A new appreciation and understanding of competition will require joint force commands to articulate strategies with ends that envision how the Joint Force commander will (1) change the theater over time, (2) respond to changes in their theater, and (3) achieve an advantageous position to drive the conflict continuum cycle. Competition will require commands to build campaign plans that integrate, converge, and leverage national elements of latent, indirect, and direct powers. While major contingency plans will remain, the real value of contingency planning can only be found in a process that creates branch plans responding to a dynamic environment assessing how the conflict continuum is moving forward.

From our current vantage point, it is easy and tempting to say that war used to be simple. You were either at war or at peace. You could defeat an enemy who wore a uniform and have a V-Day followed by a ticker tape parade. However, parades have always been seldom and political, and the clear-cut victories that they mark will become even more increasingly rare in the future. If and when there is the next big war, there may be a “mission accomplished” moment, but we should not expect it to last more than one news cycle before new and different struggles arise. We must come to terms that binary notions of war and peace leave us blind to the world in which we have always lived in. Geopolitically, competition and conflict are in a continuous cycle and reshaping our environment. The way we think about not just military force, but all elements of national power, must reflect that, and the concept of Multi-Domain Battle, with adjustments, offers the right mental models to achieve just that. Moving forward, whether in version 2.0 of Multi-Domain Battle or in the joint concepts community, exploring and defining the impacts of competition will be critical to securing national aims now and into the future.

Note: The author would like to thank Col. Scott Kendrick, Lt. Col. J.P. Clark, and Col. (ret) Bob Merkl for their assistance in helping craft this article.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Opal Vaughn, US Army

Sounds like “Information Orgeratiins” aka another bureaucratic layer added to the decision cycle peopled by non-combat arms strap-hangers who sit in drum circles and discuss weighty topics like: “what message are we sending when we shoot artillery at someone”