Noncommissioned officers are the backbone of the Army. Right?

If so, that backbone is at its strongest with a robust program of leader development. Unfortunately, the Army does not do this well for its senior NCOs. Professional development is too often episodic, disjointed, based on—or disrupted by—operational requirements and assignment cycles, and lacks expert oversight. Although it isn’t necessarily intrinsic to any of the three pillars of leader development—education, training, and experience—mentorship as a vital component of development. Better mentorship, especially for NCOs, would be an important step toward addressing the Army’s development shortfalls.

The notion that periodic, or even monthly, counseling between leaders and subordinates is an effective developmental tool is problematic. Counseling packets for junior enlisted soldiers only remain at a soldier’s current duty assignment; there is no mechanism for them to travel with soldiers to their next duty assignment. Development starts over with every assignment and with every new leader. That is not development.

According to Army doctrine, mentorship is “a voluntary and developmental relationship that exists between a person with greater experience and a person with less experience, characterized by mutual trust and respect.” But if mentorship is a vital component of leader development, why is it a voluntary relationship?

A major aspect of leader development—and the essence of mentorship—involves seasoned leaders passing on their knowledge and skills to tomorrow’s emerging leaders. Effective mentorship is a means of ensuring individual leaders are achieving their potential, to the benefit of the Profession of Arms.

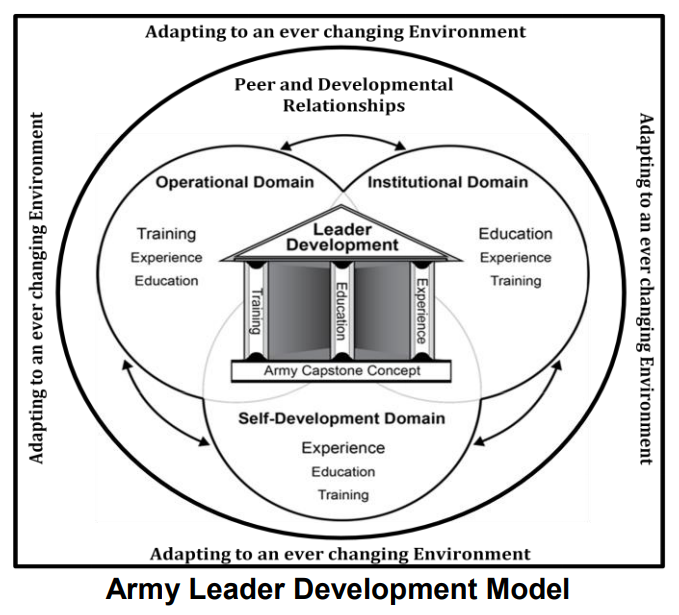

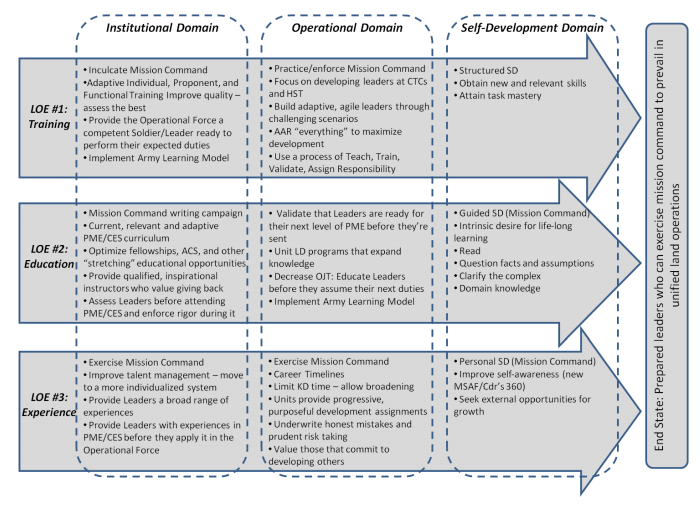

The Army needs well-written, simple, and manageable mentorship guidelines to disseminate throughout the ranks. But the guidance it does provide is rather complicated. Expecting a leader to look at the development lines of effort depicted below and immediately understand how to mentor his or subordinates is insufficient.

The Army’s officer and NCO leaders are the custodians of organizational history, culture, and values, and they are responsible for passing these to the next generation. As mentors, their role is to identify individual talents and develop those individuals into confident and competent junior leaders.

The best-known example of military mentorship is that of Maj. Gen. Fox Conner and his relationship with subordinates, including, George Patton, George Marshall, and Dwight Eisenhower. Though he retired in 1938, his mentorship would shape the Allied victory in World War II.

During his mentorship of Eisenhower, for example, Conner assigned Eisenhower mandatory readings, allowed him to attend military briefings, and instilled in him three maxims: never fight unless you have to; never fight alone; and never fight for too long.

Conner and Eisenhower’s relationship is a shining example of successful mentorship. Unfortunately, while thinking through the issue of mentorship and conducting research on it, I have not come across a similar case from within the NCO corps. Does this mean that NCO mentoring does not happen? Of course not. I have personally been mentored by great senior leaders throughout my career. Nevertheless, because of the lack of systematic training—and a consequent lack of understanding—too many enlisted soldiers miss out on the chance to have a relationship like that of Conner and Eisenhower with their own leadership. And as they move into the more senior NCO ranks, they do not have a foundational understanding of what effective noncommissioned officer mentorship looks like.

As a result, junior NCOs become predisposed to simply watch great leaders in action and mimic their examples, instead of asking those leaders to become their mentor. While learning by example is important, it cannot wholly substitute for learning through education. And without expectations for mentorship from junior leaders, more seasoned leaders might be incentivized to place their personal careers above the NCO corps and fail to give back to the Army. This is not an indictment of those leaders; such a reaction is natural if mentorship is not prioritized institutionally. This is how mentorship takes a back seat in leadership development.

It is intuitive why leadership is so critical to success in the Army, as “the process of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization.” But in a military context, leadership is often understood to revolve around particular tasks or objectives—accomplishing the mission. What happens absent a particular task or mission? What happens after it is completed?

This is where mentorship comes into play, and why it is needed in the Army. Mentoring is the vital ingredient that strengthens the foundation—and, as an ongoing practice, keeps it strong. It is through effective mentorship and leader development that leaders can influence their subordinates continually, outside the context of a specific goal or mission.

Finally, because mentorship is a long-term commitment and ongoing process, mentors have a unique opportunity to influence long-term character development.

I believe mentorship should be made a key leader developmental requirement, not a voluntary system for leaders. Leaders should be required to select a younger soldier (or soldiers, keeping in mind that mentoring too many soldiers diminishes its effects for each) who they can mentor. This should not replace the Army’s traditional counseling method, but would complement it. In practice, for the NCO corps, where a culture of mentorship is most lacking, this can be annotated on the enlisted soldiers noncommissioned officer evaluation report.

One final point: a mentorship relationship does not only enhance the development of the mentored soldier; it does the same for the mentor. Through this genuine interaction between two professionals, valuable skills and ideas are transferred, and both become more effective leaders and members of the Profession of Arms. Nowhere will this be more impactful than in the NCO corps.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Vincent Byrd