American military personnel study history as an essential component of their professional education. Military history provides the analogies by which they communicate, and the lens through which they view current military problems. Phrases such as “another Pearl Harbor” or “another Maginot Line” or “another Vietnam” convey common perceptions of the past and influence military professionals’ common thinking about the present and future.

But what if the military history they study is wrong? What if the military history they study fosters a strategic culture that is inconsistent with their strategic reality?

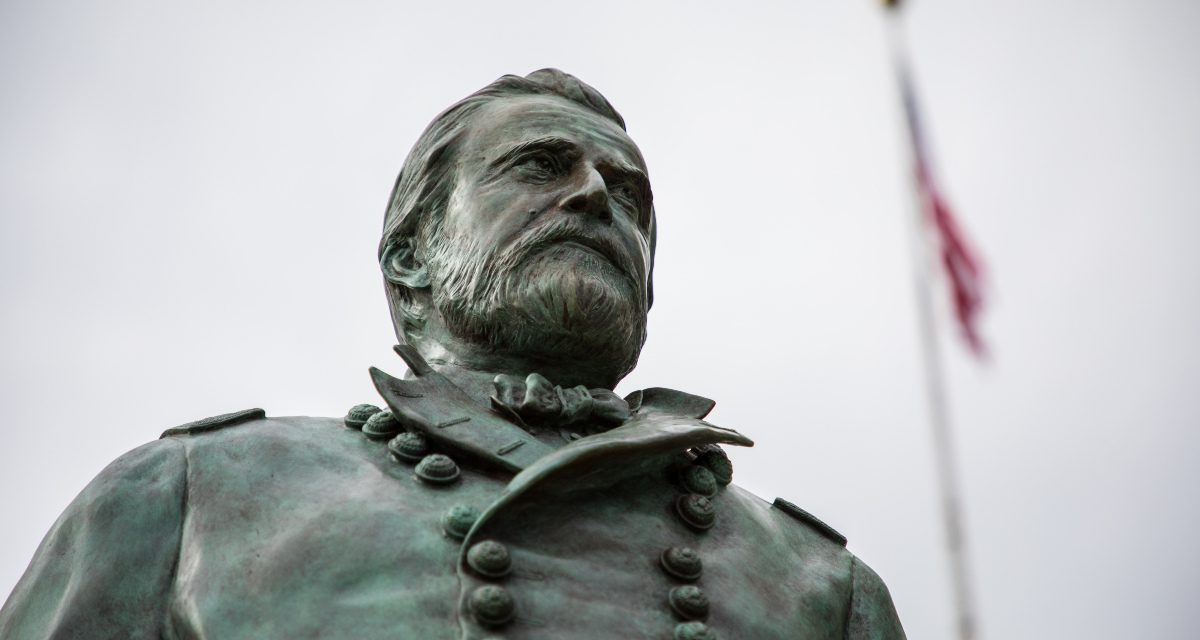

Central to the study of American military history in the last three decades of the twentieth century was The American Way of War, a history of American military strategy and policy written by Professor Russell F. Weigley. He argued that the American way of war is based on a strategy of annihilation: the aim of the US armed forces in war is to destroy the enemy’s capacity to continue the war, so that the enemy’s will collapses or becomes irrelevant. This is the war fought by Grant and Sherman in the American Civil War, when they fought campaigns of attrition fueled by the industrial capacity and larger population of the North to destroy the capacity of the South to continue the war. World War II was fought by students of the American Civil War. Among them were Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton, and Spaatz in Europe; MacArthur, Nimitz, Halsey, and Spruance in the Pacific. Our study of military history has influenced us to believe that the role of the American military is to defeat the enemy’s armed forces and destroy the enemy’s economy, at which time its mission is accomplished and it becomes a supporting player in the strategic arena. In World War I, this was actually the case. After the armistice in November 1918, the US Army participated in the Allied Powers’ occupation of Germany until the peace treaty was signed at Versailles in July 1919, and then most of the US soldiers came home to celebrate the victory (although even in this case the First Division remained part of the Allied Army of Occupation until July 1923).

The post–World War I period, however, is the exception that proves the rule. The American Civil War did not end at Appomattox, any more than the American War of Independence ended at Yorktown, World War II ended on V-E and V-J Days, or the Iraq War ended with the fall of Baghdad. After Yorktown, Washington furloughed most of the Continental Army but it remained an army in being until after the British withdrew from New York City on Evacuation Day—November 25, 1783—two years later. Twelve years of Northern occupation and counterinsurgency followed Lee’s military surrender at Appomattox, until the Northern and Southern leadership reached a political settlement in the Compromise of 1877 at the Wormley Hotel in Washington, DC. The compromise resulted in the inauguration of President Rutherford B. Hayes and the withdrawal of Northern troops from Louisiana and South Carolina. The US military occupied Japan and Germany until peace treaties were signed in 1952 and 1955, respectively. The fall of Baghdad ended major combat operations in Iraq, but martial law was not declared or established. US commanders believed their mission was complete when the Iraqi army collapsed. They ignored their legal and moral obligations to restore order and impose interim military governance over occupied territory. Despite the futile efforts of leaders like Gen. Eric Shinseki who knew better, the poorly planned and executed consolidation and stabilization effort resulted in an eight-year insurgency ending in a unilateral US withdrawal, not a peace treaty or a stable and enduring political outcome.

The “So what?” is that our study of American military history has failed our profession and our nation. American military history as taught in professional military education institutions (and more generally in our public education system) is wrong and fosters a strategic culture inconsistent with strategic reality. Here is what American military history should teach us:

1. Major combat operations are critical but not decisive. Military victories are transitory and at best establish the conditions necessary to achieve a favorable and enduring political settlement.

2. Post-combat consolidation of military gains, stabilization of the conflict-affected area, and reconciliation of the warring parties are decisive because they translate military success into a favorable and enduring strategic outcome.

3. The civil population gets the deciding vote on who wins and who loses. The struggle for legitimacy, credibility, and influence is as strategically important as the struggle to attrit and destroy the enemy’s military forces and economic warfighting capacity, and ultimately, may be more decisive.

4. The US armed forces are legally and morally responsible for the military governance of liberated or occupied territories and their populations until a legitimate and credible civil authority formally relieves them of their area responsibility. We expect privates to obey their first general order of guard duty: “I will guard everything within the limits of my post and quit my post only when properly relieved.” We should expect nothing less from our generals.

5. Leaders must plan and prepare for the worst-case scenario: a five-year stabilization campaign, including interim military governance, until conditions in the operational environment permit the transfer of area responsibility to a legitimate and credible civil authority. Why five years? Because that assumption requires planning for force rotations that can be curtailed or extended as the actual situation unfolds.

6. The US armed forces must structure a mix of active and reserve component forces adequate for protracted post-combat consolidation and stabilization campaigns commensurate with the major combat operations that precede them. Our nation cannot afford to maintain sufficient active military forces to conduct these campaigns, which will require a different mix of forces. Active forces should be relieved as soon as practicable to reconstitute and prepare for future combat operations. Reserve forces should be mobilized and trained as a consolidation and stabilization force to replace active forces.

7. Professional military education must place greater emphasis on the human aspects of military operations. The US Army planned for the military occupation of Germany and Japan years in advance, but the occupation forces did not have significant training in civil-military operations or military governance. The attrition rates in 1944–1945 resulted in units filled mostly by replacement citizen-soldiers who improvised within the guidelines established in War Department and theater army plans crafted by senior officers with superior professional military education than their successors receive today.

How should the US armed forces today apply these lessons to their thinking about our two great-power adversaries, China and Russia? First and foremost, the desired strategic outcomes should be indefinite sustainment of favorable balances of power and avoidance of direct armed conflict with either great power. Second, contingency planning should begin with the desired strategic outcome of the war, not how to fight it. Before asking How should we defeat Chinese or Russian regional aggression?, we should first ask, What strategic purpose is the war supposed to accomplish? and What does the desired strategic outcome look like? Are we fighting the war to prevent China or Russia from reversing a regional power balance in its favor? To prevent China or Russia from establishing a sphere of influence over its near-abroad? To preserve the sovereignty and territorial integrity of a treaty ally? To retain the US position as the preeminent power on earth? The answers to these questions should frame the problem of how to defeat China or Russia militarily in a long-term, globally integrated campaign. The solution to this problem must include the post-combat actions necessary to consolidate military gains, stabilize conflict-affected areas devastated by combat operations and the economic consequences of the war, and foster national reconciliation with former enemies, to restore a favorable balance of power and avoid another war. Are the associated costs and risks worth the desired strategic outcomes, or must our nation reconsider what alternative strategic outcomes are acceptable, even if undesirable or unfavorable?

Outcomes-based strategies will be critical to reversing the trend of US armed forces winning every battle, prevailing in every campaign, and losing every war it has fought since 1955. The first step: fostering a more accurate understanding of American military history, especially in professional military education.

Col. (ret) Glenn M. Harned is a retired Army infantry and Special Forces officer and Army strategist. He is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School, Army Command and Staff College, Army School of Advanced Military Studies, and Marine Corps War College. He commanded a Special Forces battalion and Special Operations Command Korea. He has worked as a defense consultant since 2000, focusing on special operations and irregular warfare policy, strategy, and force development issues.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Michelle Eberhart, US Army

This should be required reading for every officer, senior NCO, policy maker, members and staffs of the Congressional defense and intelligence oversight committees; and American voter. “Hubris goes before the fall”…our self denial about our perfect battle winning and and war losing record since 1953 (sorry Glenn but you have to account for Korea too) is a harbinger of a tremendous defeat.

I agree that the United States military has generally fought wars of attrition, appropriately or not, but how is that the fault of the history classes? Nearly ever aspect of a career in nearly every warfare community is about efficient force management and using force to achieve combat effects as requested by COCOM or national leadership. Junior- and mid-level leaders only know attrition.

I don't realistically expect junior leaders to worry too long on deeper strategy, and I don't want them to do so without proper time and resources, but senior leadership needs to fill that role. For the incredibly complex strategic problems we face, that means senior leaders need to specialize in and master a strategic problem set.

This would have complicating effects on the GOFO/SES levels of the DOD, with diverging groups focused on each geographic area and aspiring to COCOM leadership in that AOR, but they wouldn't be easily transferrable between groups and also couldn't spend much time in CONUS-focused billets. How many generals would commit to ten years overseas to become a COCOM commander?

Not sure, but those who do may be who we need.

Overall some very valid points here and I think the US military has neglected what happens after the fighting ends. Quick note on one passage above ("senior officers with superior professional military education than their successors receive today"): Many of those officers studied a lot on their own time, they focused on basics, and the institutional demands were much less than they are today (the Scales 'too busy to learn' argument) . . . And I'll bet most of us have seen examples of military leaders taking pride in their lack of intellectual curiosity.

This guy gets it!

"And I'll bet most of us have seen examples of military leaders taking pride in their lack of intellectual curiosity."

Ed, do you know any Army officers? Because your comment above makes me think you do not.

Well, Ziv, I was an Army officer for only 20 years. But I won't waste any more time on someone else's space.

An excellent article.

The questions, "Before asking How should we defeat Chinese or Russian regional aggression?, we should first ask, What strategic purpose is the war supposed to accomplish? and What does the desired strategic outcome look like?" are wise questions to ask but not sufficient.

I think the Bush administration probably considered these types of questions before launching OIF, but provided themselves unrealistic or even fantastical answers about what the war was supposed to accomplish and what the desired strategic outcome was. Namely, a reordering of the Mideast and SW Asia and the birth of a Jeffersonian democracy allied with the USA. The putative justification for the war, the threat of WMD, turned out to be vastly exaggerated and war didn't achieve any of it's strategic purposes.

Rumsfeld et al did not competently anticipate that tribal and sectarian conflict that would ensue after deposing the dictator of Iraq, and therefore wasn't able to perform a realistic cost benefit analysis of the war. It's strategic incompetence to have a "cure" that is many magnitudes of order worse than the "disease."

So perhaps a couple of additional questions should be asked: "Are we accurately perceiving the threat the opponent poses to our interests? Are we being honest with ourselves about our motivations for taking this action? And, are we being honest with ourselves about how much blood and treasure we will end up spending to take this action?"

Yep. Remember we thought we would be welcomed with open arms based on faulty analysis from corrupt expatriates. They told us what we wanted to hear.,,,,, cognitive bias.

With regard to post-war activities, which are consistent with one's desired strategic outcome, it appears that, in modern times, one of two choices has generally been made:

a. To make as few changes as possible to the defeated nation’s constitutional, political, economic, social and legal orders — i.e., those governing orders that were present, in the subject country, before the conflict began. (This appears to be the primary requirement of international law; this, given international law’s principal objectives of “stability” and “sovereignty?”) Or, in stark contrast,

b. To introduce fundamental changes in the constitutional, political, social, economic, and legal order within the conquered country — this, so as to deal with what one believes to be the “root causes” of the conflict. For the U.S./the West, examples of such believed "root causes" include the lack of a modern Western way of life, the lack of a modern Western way of governance, and the lack of modern Western values, etc. "Transformation," thus, has been the choice that has frequently been made by the United States since World War II. (A choice which, accordingly, appears to be in direct contradiction to the international law "norm" outlined at "a" above?)

Sir Adam Roberts, in his “Transformational Occupations: Applying the Laws of War and Human Rights,” addresses these matters. Here is an excerpt from the very beginning of his such paper:

“Within the existing framework of international law, is it legitimate for an occupying power, in the name of creating the conditions for a more democratic and peaceful state, to introduce fundamental changes in the constitutional, social, economic, and legal order within an occupied territory? This is the central question addressed here. To put it in other ways, is the body of treaty-based international law relating to occupations, some of which is more than a century old, appropriate to conditions sometimes faced today? Is it still relevant to cases of transformative occupation—i.e., those whose stated purpose (whether or not actually achieved) is to change states that have failed, or have been under tyrannical rule? Is the newer body of human rights law applicable to occupations, and can it provide a basis for transformative acts by the occupant? Can the United Nations Security Council modify the application of the law in particular cases? Finally, has the body of treaty-based law been modified by custom?

These questions have arisen in various conflicts and occupations since 1945 — including the tragic situation in Iraq since the United States–led invasion of March–April 2003. They have arisen because of the cautious, even restrictive assumption in the laws of war (also called international humanitarian law or, traditionally, jus in bello) that occupying powers should respect the existing laws and economic arrangements within the occupied territory, and should therefore, by implication, make as few changes as possible. This conservationist principle in the laws of war stands in potential conflict with the transformative goals of certain occupations.”

Question:

Based on the information that I have provided here, which of the two choices that I have described above (see my first paragraph) should (a) drive our planning re: (b) our post-war strategic objectives for adversaries such as Russia and China?

I think before we should ask ourselves whether we should keep a defeated and occupied China's or Russia's institutions or completely overhaul and transform them is putting the cart before the horse.

Would we ever even contemplate occupying China, or even Russia? Would we ever get into the type of war in which an occupation would be an option – a land campaign on Chinese or Russian territory? That would be a very heavy lift to project power that deep, and even more important, an existential threat which would almost certainly result in existential weapons being employed by the defender.

I think if we have a war with China or Russia it will not be primarily on their territory, but on the periphery or in proxy states.

Thought No. 1:

Do you believe that, in the periphery areas and/or in proxy states, that you have noted above re: our conflict with China or Russia above; do you believe that in these areas — both in peace and in war — consideration as to the two choices that I have identified above will:

a. Not only come into play but may, should (or indeed "must?")

b. "Drive" our planning for and execution of our operations (both pre and post "war?")?

Thought No. 2:

Although the Cold War with the Soviet Union also was not "conducted on their territory," might we agree that — in the execution of the post-war phase of this conflict — the "transformational" goals (outlined at choice "b" in my initial comment above):

a. Not only came into play but, indeed,

b. Defined "victory?" (As incomplete and fleeting as such "victory" may have been.) In this regard, consider the following re: the 1990 Charter of Paris:

"Charter of Paris for a New Europe:

The multilateral process initiated in Helsinki was further developed during the second CSCE Summit, held in Paris in November 1990, which laid the foundations of the institutionalization process and defined a common democratic foundation for all participating states in a new Europe free of dividing lines. The Charter of Paris enshrines a set of common values affirming the direct relevance to security not only of the respect for human rights but also of democratic governance and a free market economy.

Download this file (Paris summit 1990 – Charter of Paris for a New Europe.pdf) Paris summit 1990 – Charter of Paris for a New Europe.pdf [ ] 69 Kb"

(From the "International Democracy Watch" website.)

Conclusion:

In consideration of the periphery areas and/or proxy states information — provided at my "Thought No. 1" above — and in consideration of the "great power"/"Cold War" information provided at my "Thought No. 2 " above, might we agree that:

a. Re: our planning for conflicts with China and/or Russia (and/or their proxies, etc.),

b. A decision must be made whether to follow and pursue:

1. "Old" international law (requires not messing with the political, economic, social, value, etc., norms and institutions of the subject country; this, so as to honor "sovereignty," maintain "stability, or return to "stability" as quickly as possible after a conflict). Or, in stark contrast, to follow and pursue:

2. "New" "transformational" international law (as discussed by Sir Adam Roberts in the article from him that I point to in my initial comment above)?

Generals are not the ones responsible for deciding when to cede control to [foreign] civilian authority; that is decided by our civilian authority and implemented by the uniformed chain of command. Iraq was a post combat cluster because the civilian authority in this country said "we will be greeted as liberators". There is no need to assign that failure any lower than the highest ranks of that Administration and its arrogant and flawed war objectives.

We should also be very careful about taking universal lessons out of the WWII and immediate post-war era, as that was exceptional (both for this country and the rest of the world). War on the Rocks had a very good article a couple of months back on the need for a blue theory of victory, very much along the lines of the questioning in the penultimate paragraph here.

This is an inaccurate reading of Weigley's book American Way of War. Weigley argues that the US has generally pursued a military strategy of annihilation in wars since the Civil War, but argues this approach was flawed. His book is a critique of one-dimensional military strategy, He argues that implementation of annihilation strategies has been counter productive, in fact that is the fundamental argument of the book. His book is an intellectual history of American strategic thought, not a history of American wars. If you are reading AWoW for a detailed history of how the US Civil War was fought, it is the wrong book for that.

Thank you for an excellent article. One hopes that in addition to military personnel in training for the future, it will be read by politicians who, if elected, will, in directing a war, implement its good advice.

Yes Sir, excellent point. Having been in Iraq and Afghanistan long after both should have been concluded, the issue keeping our forces there was the lack of strategy for transition and defining our interests in those places. Those actions are defined by the political leaders of our nation.

I wonder where Col. (ret.) Harned gets his ideas about how military history is taught, and whether he ran this criticism by any of the people who actually teach it before he submitted this to MWI. Weigley's book is almost fifty years old, after all.

That how you here today don't forget that history without them we don't have usa today

Lessons learned is an important aspect of leadership development. Theories are not always practical in combat. Our successes in combat operations are a direct result of lessons learned.

I am not sure if you served in Iraq or Afghanistan, but I did. I can tell you that after the fall of Baghdad, we did not "ignored their legal and moral obligations to restore order and impose interim military governance over occupied territory".

Nearly every Infantry LTC was assigned sectors to establish order, work with local shieks, and develop plans to rebuild, while at a much higher level, the secretary of state coordinated national elections, developed a new national currency, laws and order, recruit and train a national police force in conjunction with national and occupying leadership.

Rather than pillage the wealth of the nation (Iraq oil) as accused, we dumped trillions of dollars into these countries economies. These wars were not fought against men in identifiable uniforms and adaptations were made from previous lessons learned.

Did Weigley serve and protect our country with any of our military branches ? Did he serve during war time ? Did he go door to door, room to room, under beds, behind chairs, couches, tables, piles of clothes… Did he fight face to face with his only weapons being his hands and teeth ? Did he ever experience what it's like to know that there are only two choices in combat, kill or be killed. That's what my father told me about his tours in Vietnam, that's what I told my son about my tours in Iraq and that's what he'll tell his son about his tours in Afghanistan. There are no rules in combat. To defeat the enemy you must kill them. To prevent future conflicts you must destroy them. To put the world at ease from any simple threat in the future, the enemy and those who support them must be annihilated. Should we train our troops to be understanding ? To be fair ? To be supportive to the people who's goal in life is to take ours ?

Right on Steve you said it all! You should write an article. And thank you and your father for your service. My father was also a Vietnam vet and told me anybody anywhere in the nam could buy it you just prayed to the good Lord it wasn't you.

The problem is not with military history, but with POLITICAL history. Our elected political leasers are NEVER elected based on their warfighting, conflict resolution or peace making skilss, only on their economic and domestic issues skills. The imbalance is that the military experts are seldom permitted to manage the wars. Those politicians who attempt are incompetent in comparison.

This article is a classic example of a "straw-man" argument, and is flawed because it projects a view of American military history that is outdated. For example, Prof. Brian Linn of Texas A&M University critiqued Weigley's argument almost 20 years ago in "The American Way of War Revisited,"Journal of Military History 66 (April 2002) – and Russell Weigley approved of the critique and welcomed it as the advancing of scholarship. There have been numerous works that have explored other ways of American warmaking since then, from John Grenier's First Way of War to Antulio Echevarria's Reconsidering the American Way of War. Moreover, the themes that Harned claims American military history "should teach us": these are being addressed in PME, and have been been for about the past 15-20 years – just ask some of the historians who work in DMH at CGSC.

Dr. Muehlbauer, I have not attended PME since I graduated from the USMC War College in 1995. But I have worked closely with active duty field grade officers for the last 20 years since I retired, and if you are teaching these ideas in PME, they aren't learning them. Grenier's book is enlightening, and i will order Echevarria's book as soon as I finish this reply. I see no evidence in the Pentagon that your other ways of American warmaking have any traction in the US officer corps or in the crafting of strategic plans.

Colonel Harned’s excellent article should be widely read and carefully considered. His assertions are applicable to developing Leaders, and the means of their development. Hence these considerations are not limited to general officers.

Yet maybe the most damning criticism of this article might be that it’s about wallpaper options in a burning building. What if there’s a much more widespread inability to face reality? Please consider:

1. The recently-concluded Nagorno-Karabakh War stated emphatically that fleets of manned armored vehicles are as obsolete now as fleets of battleships were in 1941. Is anyone paying attention? It seems not.

2. [From a headline this very day:] Both houses of Congress agree the Army isn’t facing any of the realities of heavy-lift helicopters, across the full spectrum from the vital industrial base to future requirements. In fact, the Army has no plan at all, but hopes to formulate one in 2023! How can it be the given platform has been flying for almost 60 years, and has been continually improved, but is now so thoroughly mismanaged that Congress is required to assume complete control?

3. I recently discovered that among a squad of Soldiers going to the field in a combat theatre, the female Soldier’s large, bulging rucksack weighed less than 15 pounds. One handsome male Soldier’s rucksack was more than 100 pounds. Otherwise, the rucks averaged around 50 pounds. So how hard is it to figure out what was going on? In other words, what does a female Private have to compensate a male squad member for carrying her gear over hill and dale? Is this the military experience we want for our Nation’s daughters? The point is, as I’ve often commented upon: does anyone out there have the intellectual courage to evaluate and define physical performance standards for female Soldiers? Of course not!

I’m very sorry, Colonel Harned. Your superb analysis is falling upon deaf ears.

L.K., it is not all gloom and doom. DoD takes a long time to shift course, but there is a realization among the JCS and Combatant Commanders that what we are doing is not working. Many of the career professionals in OSD agree. In February 2019 the SecDef signed the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy. You can download an October 2020 Unclassified Summary on the internet. A comprehensive implementation plan is with the Deputy SecDef for imminent final approval and signature. Unless the new Administration cancels this effort, you should see significant institutional and operational change over the next five years to address the threat of great-power competition.

The part that misses the mark, widely, is the Generals do not get to decide. As GEN Shinseki, painfully learned, the civilian leadership decides, and they often do not have the benefit of a professional military education. The author’s points are valid, but aimed at the wrong target, rendering a potentially useful article… less than..

When the national decision-making authority hears a proposal for combat operations, the response should be, “Will combat resolve the source of the conflict that has driven the resort to organized violence? Or, simply end combat only temporarily?” Temporary peace may be the only achievable desirable outcome. For instance, why has Russia driven west so often since the 16th century, despite being halted or thrown back several times? The Confederacy lost the Civil War, but the movement for white privilege still drives conflict. Combat changes the pre-war conditions, too. Napoleon was eventually deposed, but then the ideas of the French Revolution drove conflict wherever he had ruled. The permanent or temporary nature of the desired outcome should determine the military strategy and expenditures.

Clearly the article generated some excellent discussion. From a long period of participating in and observing the progression of strategic thought, application, and effects, while there have been some doctrinaire approaches and thinking, e.g., the approach to the critique of indicated study of American military history and the "American way of war," I have experienced many fellow travelers not so wedded to the ascribed "norms" of thinking.

There have been more than a few that aggressively went to school on the indicated and most likely competition and even some not so likely competitors to understand alternative points of view and approach. Their minds were open to alternatives to how a situation might play long term and short term. And of course no military application that operates outside the domestic and opponent polities acceptance will long endure, even if we might be "victorious" in the present. And any separation of the military authority from its subordinate role to the civil authority is problematic in a strategic consideration.

But the key question…where have been/are these less "doctrinaire" thinkers positioned in the planning and decision processes at any point in the process to affect the outcomes." What "Fox Connor" function operates to mentor and position such individuals?

But one area draws specific attention and thought based on article comments and some previous discussion that touched on several related points. That area and one that has caused much personal thought is if we prevail in the active military operations context, increasingly a reality in the way gray zone operations of today are evolving and applied, what have we done to study the post operational aspects to give ourselves the intellectual tools to pursue strategy that takes us to a least problematic result. My sense is that the post active operations period is not given the attention for study that the preceding planning and operations receive up to cessation of active operations. The article does address comment to this area that causes thought but from discussion it does not seem to have been focused on sufficiently as a vital strategic area pointed toward a real optimized "sustaining" beneficial outcome.

The article was a very good thought piece that will hopefully generate more discussion.

Good answer and as you said: <i>The article was a very good thought piece that will hopefully generate more discussion.</i> My heart is not in my answer yet. I would have been more harsh.

Excellent article. I disagree with one of the author's premises however. He states: "The “So what?” is that our study of American military history has failed our profession and our nation." Not so. The problem is our officers largely DO NOT study American military history so "history" could not have failed them. They never studied it. I spent 19 years on the graduate faculty of the US Army Command and General Staff College in three departments. Most of my time was as a retiree instructor. I retired out of active duty in the history department (CSI back then). The average major or lieutenant colonel student was abysmally uninformed in history. Many had not read a single book in the year prior to attendance. In a survey, 50% of attendees at the college had a high school, or lower, knowledge level of history. Now, the college has recently cut the already sparse instruction even more. My foreign students from European countries knew more about our U.S. history than half of the Americans. We cannot fix what 16 years of prior education never achieved.

I disagree with the author on his assumption the Civil War or War of Insurrection which is the more proper description (These days Americans seem to have difficulty using the word insurrection correctly.) , the Civil War did end when the Armies of the Slave States were disbanded. At the wars end a great concern was that the Confederate government would continue in exile. We recognize the end of the War with the surrender of Lee's Army. A greater concern than the dissolvement of the Confederate government and the arrest of Jefferson Davis, was the worry if Lee and Johnson among other CSA Generals would be defeated only to have their disbanded Armies turn into guerilla movements. Neither side wanted a prolonged insurrection or insurgency. With a few exceptions. (Depending on how you define the rise of the KKK within the Southern Democratic party.)

If one believes the "Civil War" did not end at Appomattox it did not begin at Fort Sumter, Harper's Ferry or even Bloody Kansas. One might even claim it began when the first slaves were brought in chains to the USA.

The problem isn't the degree to which we recognize what is war or low intensity conflict or a counterinsurgency. I believe the problem today is our perception of reality, even history which is being redefined by a sort of hypothetical alchemy that too often and for ideological purpose turns fiction into facts. Even our imperfect understanding of how other cultures understand reality is affected. Accepting the pace of progress as something that is not revolutionary or radical but by definition genuine progress is a more gradual change even evolutionary.

The war of Insurrection was begun by the Slave states to protect their property and ownership rights, in other word slaves. Slavery was ended by the War. After years of the bloodiest conflict in American history no one wanted a prolonged insurgency least of all the north. And the imperfect end of slavery that upheld the Emancipation Proclamation and resulted in the 13th and 14th Amendments also had the evil effect of bearing America's first cancel culture, the "Lost Cause ". That took a further 150 years before it began to be addressed and debunking the Lost Cause continues making progress today. It may seem like we are taking greater strides now by removing statues, taking steps to rename streets, Army Posts, schools etc. , progress is "movement forward or toward a place. : the process of improving or developing something over a period of time." Revolutions and Radicalism based on hypothetical and sometimes mistakenly referred to as progressive history too often fail because they take too many short cuts to create a façade.

Interesting to a degree. US military history pre 1898 and post 1898 are not even the same planet. Same as that history pre 1947 to post 1947. In his list of points, a discussion about the US financially building every enemy it has had since WW2 woul be appropriate. His war of annialation is not true considering Limited War was implemented by Truman and Marshall and has been our military guideline since 1953. The last time the US truely annialated an enemy was 1865. It, the US, has been on the winning side of allied forces since then, but that was a group effort. Every combat the US has conducted on its' own since 1865 has been less than an "annialation" of the enemy.

The problem is that US military operations from the Washington PoV isn't concerned with stabilizing the newly defeated enemy. It's to create the conditions for Forever War so that Raytheon and other military contractors and tertiary and beyond camp followers who financially and politically profit from these ongoing demands for expenditure in every sense of the word can improve their quarterly reports.

I believe Eisenhower, student of the civil war, warned of such an arrangement, the Military-Industrial Complex.

The US soldier is no longer really required to defend the United States, the US is geographically and strategically all but untouchable on that front, and there is no major competitor to America's hegemony…so far.

China is the closest but even then, the combat there such as it is, is within the economic arena and the USN's mission to police international sea trade lanes. Realistically speaking boots on the ground in the Pacific isn't a major concern over having big expensive, but largely deterrent tier naval toys to put China off from misbehaving too much.

As for Russia, it is a shadow of it's former, Soviet self. The proxy conflict in Ukraine is thus more of that profit-seeking, prodding an opponent for prodding's sake level of conflict.

Realistically the US only needs a relatively small, almost token tier army, grunts with guns.

You're totally correct that US soldiers are being sent to fight and die for other countries interests, and not even for World War level threats that could eventually come back to hurt America overtly, but simply spending US treasure and blood to buy the favors of petty client states far away.

One can discuss whether there's merit in US troops fighting and dying for meta-level US interests, but suffice to say there's many many steps from shootting up Yemeni or Syrian villages and any armed locals, to defending the beaches of the continental US from an existential threat.

The United States is ostensibly a introspective democracy of some flavor, despite controversies, mission creep, and stumbling into an empire of sorts. American citizens will have to sit down together over the campfire and have a long hard discussion about where they wish to draw the line on intervention abroad, and where it is, or is not, for what it is or is not appropriate to send US troops to fight and bleed and die for.

To paraphrase an American general's famous words I now recall, it's better to make some sonofabitch die for his country. before considering sending Americans to die for theirs.