Editor’s note: This is the latest article in “Rethinking Civ-Mil,” a series that endeavors to present expert commentary on diverse issues surrounding civil-military relations in the United States. Read all articles in the series here.

Special thanks to MWI’s research director, Dr. Max Margulies, and MWI research fellow Dr. Carrie A. Lee for their work as series editors.

Americans do not subscribe to consensus norms of democratic civil-military relations. When it comes to basic decisions regarding the use of force, they are often inclined to defer to the judgment of military officers. The problem has worsened over the last two decades, even as the US public has increasingly come to view civil-military relations through a partisan lens. The lack of popular support for this basic democratic principle is disturbing on its own terms. This is also worrisome because the lack of support also poses dangers for America’s capacity to design strategy and mobilize and apply military power. We recommend that leaders push back against the deeply entrenched culture of militarism in the United States, that civics education at all age levels highlight proper civil-military relations, and that military leaders resist pressure to erode the military’s apolitical standing.

What is Democratic Civil-Military Relations?

Democratic theory demands that decision-makers be accountable to the people. As a result, while military officers have a responsibility to advise civilian politicians and officials, their judgment should not replace that of elected leaders and their appointed representatives. Policymakers, military officers, pundits, and scholars have numerous legitimate disagreements over how to ensure appropriate democratic civil-military relations, but this core principle is not in dispute. Civilians’ “right to be wrong” means further that military officers should express their views to decision-makers only behind closed doors and should not seek to shape policy by going public.

While decades of polling confirm that Americans have substantial confidence in their military, this confidence does not necessarily translate into public support for democratic civil-military norms. This state of affairs might be acceptable if democratic civil-military relations were just an elite pact—as classic scholarly work often implies. But democratic civil-military relations are not sustainable as an elite game alone. Public commitment to democratic civil-military relations keeps military officers in line and elected politicians from politicizing the military or enlisting the armed forces in domestic political disputes. Threats to democratic civil-military relations abound if the public has not bought in.

Nor, we believe, is it too much to ask citizens to grasp these norms. Every schoolchild knows the folk theory of democracy to which Lincoln gave voice in the Gettysburg Address—that democracy is, and should be, government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Democratic civil-military relations derive directly from that folk theory.

A Deferential Public—and More So Over Time

The consensus tenets currently command far less adherence from Americans than they should. As we previously reported, in June 2019 and June and July 2021, we surveyed nationally representative samples of US residents, and found that the American public is remarkably out of step with these norms. About half of Americans believe that military objections to a proposed mission should always override the president’s judgment about the utility of the operation. A significant majority of Americans are also remarkably comfortable with military involvement in public debates over military operations and policies.

The problem has gotten worse over the past two decades. In 1998–1999, the Triangle Institute for Security Studies asked Americans whether “in general, high-ranking civilian officials rather than high-ranking military officers should have the final say on whether or not to use military force.” At that time, a majority—53 percent—of respondents agreed. In 2021, just 43 percent of US respondents upheld this basic principle of civilian control of the military. In short, many Americans, and sometimes a majority, do not believe that the will of the people, through their elected representatives, should reign supreme over military preferences.

Partisan Politics at the Root

Perhaps we should not be surprised. After all, Americans’ support for democracy is more fragile than many once thought. Liberal democracy rests on the premise that the process is more important than the outcome: the system’s legitimacy derives from its procedures’ intrinsic fairness. Candidates accept defeat at the polls today in exchange for the possibility of victory tomorrow. But recent events suggest that many Americans attribute or deny legitimacy to the procedures based on the results they generate. The faith of many Americans, on both sides of the political aisle, in democracy appears to depend on whether their candidate wins the White House.

It is not surprising that these same tribal politics also govern people’s attitudes toward civil-military relations. In our 2019 survey, those who strongly disapproved of then President Donald Trump, who also tended to be strong liberals and to most distrust military officers, were oddly the most deferential to the armed forces, and those who strongly approved of the president were the least deferential. Why? Because, we argue, Trump loyalists feared that the military’s policy preferences did not align with those of Trump, and they wanted him to have free rein. Trump’s detractors were skeptical of the military, but they had even less trust in the president.

As expected, when Joseph Biden entered the Oval Office in 2021, Democrats became much less deferential to the military. However, to our surprise, Republicans became only slightly more deferential—for partisan reasons. Repeated waves of attacks against military leaders by right-wing politicians and pundits, in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd protests and election fallout, left Republicans doubtful that the military was on their side. As a result, even with Biden in the Oval Office, a plurality of strong Republicans opposed policy advocacy by senior military officers. Democrats, meanwhile, became increasingly confident that senior military officers shared their policy preferences, and so they became surprisingly happy for the brass to speak out.

Ultimately, for partisans across the spectrum, the military in general, and especially the top brass, have become a central actor in domestic political strife, as an ally or adversary. Among the small minority that expressed distrust in the armed forces, a large majority of Republicans (64.6 percent) said it was because the military is political—compared with just 35.8 percent of Republicans who felt that way in 2019. Notwithstanding widespread reports that Americans’ trust in the military has recently fallen, it remains impressively high by historical standards. The greater danger is that the US military may become, in the eyes of the public, a political actor just like any other in Washington.

Implications and Dangers

Both the veneration and vilification of senior military officers harm the United States’ capacity to design strategy and mobilize and apply military power. We foresee four dangers at the intersection of growing partisanship and civil-military relations.

First, a public inclined to defer to the military impedes the nation’s capacity to devise and sustain a coherent national security policy. Public deference to the military not only undercuts democratic accountability—which is normatively valuable on its own terms—but it also bolsters the military’s capacity to drive foreign and security policy, at the expense of other policy tools and government agencies. Rosa Brooks has recorded in memorable detail how, after 9/11, “everything became war and the military became everything.” Even as the Global War on Terror waned, the uniformed military’s power and prominence did not. Secretary of Defense Bob Gates’s warning in 2007 that US statecraft had become dangerously skewed toward “the guns and steel of the military” and his clarion call for “a dramatic increase in spending on the civilian instruments of national security” stand out—not just because they were strikingly rare, but also because they were strikingly futile. From a budgetary standpoint, very little has changed—notwithstanding which party controls Congress or the White House. The FY23 US defense budget weighs in at nearly $800 billion, compared to just $66 billion in FY22 for the Department of State and other international programs. So too, public deference sustained America’s longest war, in Afghanistan. It dragged on for years, whether Democrats or Republicans were in charge, in part because, as the Washington Post‘s Afghanistan Papers highlight, military leaders presented rosy prognoses in public that often went unchallenged and in part because the top brass remained committed to the war and used its unique advantages to restrain civilians whom they saw as fickle.

Second, good policymaking rests on respect for, and critical engagement with, military officers’ expertise when it comes to the use of force. While it would be a mistake to defer to officers’ judgment, and outsource military policy to them, it would be equally foolish to design military policy without, or discounting, the input of military officers. When the military comes to be seen as just another political actor, policymakers may be inclined to welcome or dismiss officers’ professional judgment based on their perceived politics. Indeed, if the military is viewed as just another political actor in a divided and polarized Washington, candid discussion over the use of force will be a casualty. Reportedly, on various occasions, Trump belittled the military’s top brass—calling them, among other things, “losers” or “babies and dopes”—which reflected the low esteem in which he held their professional advice and which perhaps discouraged senior military officers from giving the president frank guidance. In fall 2020, Trump publicly questioned the senior military’s integrity, accusing them of corruption. It was a declaration that it was open season in right-wing circles on General Mark Milley and others, questioning not only their politics and alleged “wokeness,” but their competence.

Third, conceiving of the military as a political actor invites partisans to treat it as a valuable political resource. If this seems far-fetched, it is because the US tradition of civil-military relations has, since the late nineteenth century, allowed the military to govern itself according to its own norms. But staffing bureaucracies—military or otherwise—with partisan compatriots is tried-and-true, and across the world it is a regular occurrence. Militaries whose staffing and promotion are based on merit—rather than political considerations—perform better on the battlefield. Russia’s abysmal battlefield performance in Ukraine reflects in part how badly corrupt and politicized militaries fight. A competent military, reinforced by strong norms of meritocratic rather than political advancement, leads to more trust in the institution from those within and outside the corridors of power.

Fourth, belief that the military has been, or even may be, captured by partisan interests can harm recruitment. If partisans come to believe that the officers setting military policy are the enemy of Americans like them, they will be hesitant to send their children into that institution’s ranks. Even the fear of political intrusion at regular intervals, along with shifting power balances in Washington, would likely dissuade people from signing up for a military career. Such self-selection deprives the military of talent, and undermines the diversity of the force. Likewise, conceiving of the military as a partisan actor may damage retention, if service members doubt they will advance on their merits. So far, the evidence is meager that right-wing attacks on the officer corps’s “wokeness” has much affected enlistment. The current recruitment crisis is probably much more the result of a historically tight US labor market. But right-wing vilification of the top brass seems likely over time to depress enlistment among the most “propensed” recruits and their “influencers.” If other forces continue to pull potential recruits away from military service, politicization heaps gasoline on an already burning fire.

What Is to Be Done?

To address the problem, we must properly diagnose what ails the public’s views of the military. A national culture of militarism has long glorified the nation’s soldiers and officers as the best and the brightest, as the most noble of citizens, as heroes and as self-sacrificing patriots. Politicians have often led this veneration. Their recent turn to vilifying senior military leaders is equally dangerous. But politicians cannot bear all the blame for making the military a political football. The active duty military has, in various ways, subverted democratic control and contributed to public confusion about the military’s role, from openly disparaging presidents to threatening resignation to making public statements on policy. Retired generals have regularly traded on their military credentials and embraced an active role in politics and punditry. If the public is confused, it is partly because military officers have confused them.

There is no panacea for these deeply rooted ills, but we can make progress.

First, civil-military relations should be an essential element of Americans’ civics education, and that education needs to be lifelong. The Department of Education, in collaboration with the service academics, should develop a national curriculum for civil-military relations in high schools. Required university courses on US politics or history rarely spend any time on civil-military relations—but they should. For a mere fraction of the military’s budget, experts in civilian universities, service academies, and professional military education institutions could develop these courses. A slightly larger fraction of the budget could support building and promoting free online course content to engage American adults outside of institutions of higher education. And, of course, those Americans who serve in the military, at all levels, need more regular training in democratic civil-military relations, so that they resist the urge to overstep their bounds. They also need more detailed, scenario-driven instruction, so they are well positioned to respond appropriately when civilians do not.

Second, both civilian and military leaders need to push back against the country’s culture of militarism. Rather than reflexively thanking soldiers for serving heroically, politicians should thank them for serving democratically—that is, for obeying the will of the people and their elected representatives. Rather than reproduce the mythology of the citizen-soldier, politicians should speak more honestly about what drives soldiers and officers, about their foibles as well as their strengths, about the nature of modern soldiering as a kind of dangerous work. Today’s professional soldiers are not the citizen-soldiers of yore, but that does not make them less worthy of our respect or our skepticism. The Pentagon needs to stop actively sponsoring militarist mythmaking at our nation’s sporting events and movies. Civilian and military officials should both be encouraged to talk more frequently, and more openly, about the fragility of America’s civil-military compact. These are admittedly small steps, but culture changes gradually.

Third, politicians, as well as all active duty, reserve, former-serving, and retired service members regardless of their seniority, need to work together to restore the military’s apolitical standing. Politicians routinely make the military into a political prop. In this environment, any action officers take—whether performing their duty or resisting—can give the appearance that they are playing politics. Retired generals who claim a right to speak based on their new civilian status while simultaneously trading on their military credentials also blur the image of the military as apolitical. Informal measures bolstering norms can be critically important. Everyone—civilians and military, including junior service members—has a part to play. Intense public criticism, from both sides of the aisle, should follow when politicians give political speeches to uniformed military, or with them in the background, or when politicians choose to announce major foreign policy initiatives at military bases or academies. But there may be a place for more formal measures too. For instance, the military could develop regulations limiting how retired officers can play on their credentials—and hold their pensions hostage.

If our recommendations seem a bit hortatory, it’s with good reason. If we have learned anything in recent years, it is that institutions and laws are important, but they are no match for individuals determined to overthrow the system. What the federal judge Learned Hand said in 1944 about liberty applies equally to democratic civil-military relations: it “lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there[,] it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.”

Ronald R. Krebs is a professor of political science at the University of Minnesota. He is also the editor-in-chief of Security Studies.

Robert Ralston is a lecturer at the University of Birmingham.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

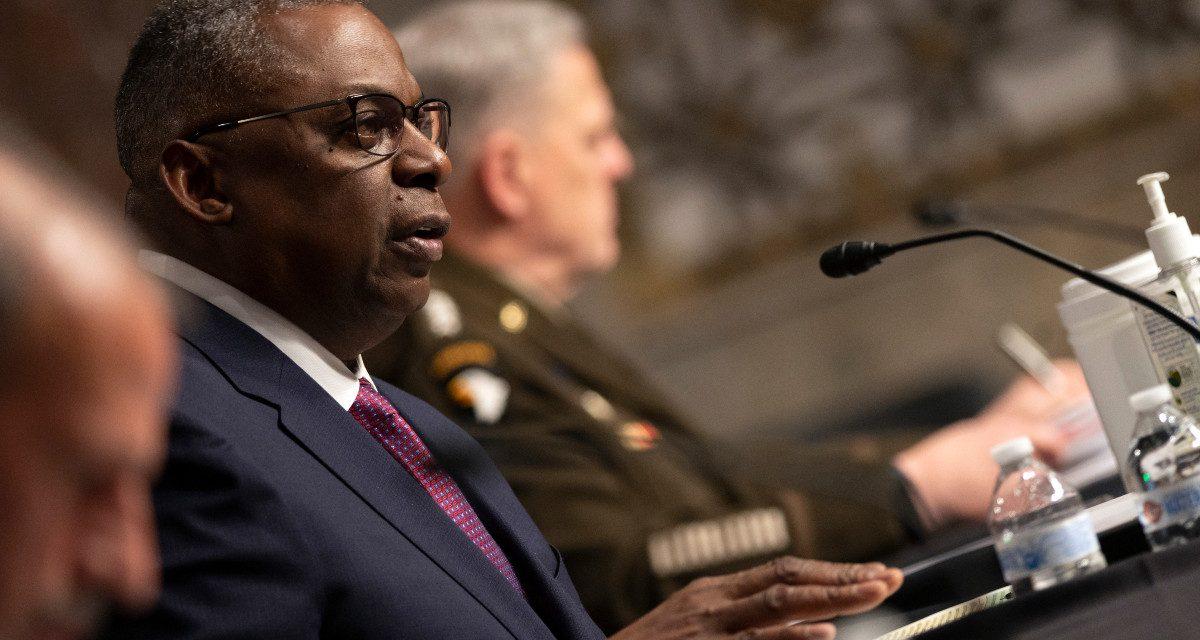

Image credit: Lisa Ferdinando, DoD

As to the article above, let's consider this quote from the major section therein entitled "Partisan Politics at the Root."

"Ultimately, for partisans across the spectrum, the military in general, and especially the top brass, have become a central actor in domestic political strife, as an ally or adversary."

Question — Based on the Above:

Should we agree with the contention above that the military in general, and especially the top brass, have become a central actor in domestic political strife, as an ally or adversary of one side or another?

Or, more correctly:

Should we say that the military in general, and especially the top brass, have become a central actor in national security matters/affairs; THIS causing them to be considered as an ally or as an adversary of various parties?

(Note that, from the latter perspective that I provide above, it is not "Partisan Politics" that is "at the Root" of these such civil-military relations problems/matters but, rather, "national security.")

Re: my initial comment above, and my suggestion therein that the military in general, and especially the top brass, have become a central actor in — not partisan politics — but, rather, national security matters/affairs; THIS causing them to be considered as an ally or as an adversary of one side or another,

As to this such suggestion, consider the following:

"Even more telling than its use of elite opinion in 'Lawrence' was the (U.S. Supreme) Court's unembarrassed reliance on elite view to determine the scope of a highly contested constitutional antidiscrimination norm in 'Grutter." Relying extensively on amicus briefs submitted by elite corporate, military, and educational authorities, Justice O'Conner, writing for the majority, asserted the following:

"Major American business have made clear that the skills needed in today's increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints. What is more, highly ranking retired officers and civilian leaders of the United States military assert that, 'based on their decades of experience, a highly qualified racially diverse officer corps … is essential to the military's ability to fulfill its principle mission to provide national security.' "

(Item in parenthesis above are mine. See the last paragraph on Page 698 of the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper "Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court's Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty.)