In February 2024, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced the creation of the Unmanned Systems Forces. It is no secret that the Ukrainian military has used drones to great effect. Its units continue to innovate with drone tactics, techniques, and procedures and effects in the air, land, and maritime domains. Both belligerents in the Russia-Ukraine War have pledged to build over a million aerial drones each year to fill the skies. Even with the extremely innovative use of the drones (mine laying, incendiary delivery) already observed in Ukraine, history will show that the most important attribute of drones has been their ability to serve as economy-of-force systems. In a grinding war of attrition, drones have allowed the Ukrainian military to protect its limited combat power and threaten a much larger combat force across multiple domains.

The Unmanned Systems Forces that Zelenskyy announced amount, effectively, to a drone corps. US policymakers have taken note of the effectiveness of drones in the conflict and a drone corps may also be coming to the US Army. A draft 2025 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) from the US Congress directed the Army to establish such a corps as a basic branch. The language did not make the US Senate’s version of the NDAA—however, it is an understatement to say that drones and their effects are here to stay on the battlefield. Drones may not be revolutionary in their impacts, but they are a creditable and enduring enabler—an enabler that continues to threaten the hegemony of traditional branches like artillery and the once dominant mass of infantry and armor. The Army and DoD more broadly are striving to innovate with drones, but standardization, training, and tactics vary. The DoD Replicator program’s primary mission is to increase the available drone inventory, but how effective is a deep magazine of drones without subject matter experts to operate and employ? This trend of drones’ growing impact will likely continue as they are paired with AI and other technologies. But in an imagined near future where the NDAA has passed with the drone corps language intact, what form should such a corps take?

The Needs Statement

It is no secret that the US Army (and other services) faces recruiting challenges. The force would certainly struggle to quickly fill and train its ranks for a mass mobilization. This problem is compounded by the increasing speed with which the character of war is changing—which means the Army would not just need a sufficient number of people in the event of a large-scale conflict, but people whose knowledge grows at a pace commensurate with battlefield evolution. A case in point is the war in Ukraine’s repeated demonstration of actions and counteractions as both sides seek to ensure drone primacy. The most recent example is fiber-optic tethered drones largely immune to electronic warfare effects.

Drones, if managed appropriately, are a quick, cheap, economy-of-force capability, but one evolving rapidly enough that it requires a focused and professional stewardship—a drone corps. As the Army closes most of its cavalry squadrons there also remains the requirement for reconnaissance and security operations. These are historically an economy-of-force mission and drones are well suited for it when supported with traditional enablers. In a cavalry squadron, the planning, collection, and dissemination of the intelligence requirements was a primary focus of the squadron staff. Now the task is spread across multiple headquarters with no real unified ownership. A drone corps would help to fill this gap.

The creation of a drone corps is the next evolutionary step in the critical management of these warfighting systems. The training, maintenance, and implementation cannot be the secondary duty of a brigade aviation officer or a proactive noncommissioned officer or officer in a battalion. A drone corps will ensure development of systems and branch professionals along avenues across the DOTMLPF spectrum (doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, and facilities). Infantry, sustainment, and fires battalions are all led by professional officers and noncommissioned officers from those branches. Drones and their employment have evolved to the point where those domain systems need the same stewardship. The Army cannot afford a disjointed implementation of drone doctrine or of tactics, techniques, and procedures. The systems need a champion to drive progress inside the Army and refine requirements for industry.

Waypoints to Follow

So, what would a professional drone corps look like? Among US special operations forces (SOF), the SOF truths provide a critical baseline understanding of purpose and a north star for the special operations community’s culture. A drone corps would be well served by replicating this model and building itself around a fundamental set of drone truths.

- Drone warfare will be an enduring capability and threat on the future battlefield. Drones are cost-efficient, simple, and quickly mass-produced. They allow individuals and states the ability to compete with larger adversaries. People will find a way to keep drones in the fight.

- Drones do not replace the warfighter. Even with drones on the battlefield, manned maneuver forces will still be needed to retain ground and fight. Humans must still be on the loop for maximum efficiency. AI is efficient, but—because it does not precisely replicate the cognition of humans—insufficient.

- Drones are a powerful economy-of-force capability and constant enabler. Drones don’t need to rest. Instead, they allow manned forces to rest, refit, and transition to the next fight. A cheap drone can always be sent forward, preserving combat power and saving lives.

- Drone professionals, effects, and synchronization are not created instantly, but require training, planning, and time. Drone systems are relatively cheap and it does not take long to train an operator. However, it does take time to achieve synchronization and effects. Additional-duty operators found in maneuver battalions vary in quality, flight time, and capability. Regardless of operators’ skill, they will eventually leave their units. Subject-matter experts and repetition are required to ensure drones are well positioned and the data they provide is appropriately analyzed.

If these truths form the basis on which to establish a drone corps, that corps should also be constructed with several foundational principles in mind. First, the drone branch is responsible for the operations, training, and testing of the systems. This includes air, ground, offensive, defensive, unattended sensor, and resupply drones.

Second, the drone branch is fundamentally a maneuver branch with a focus on targeting and synchronization. It does not replace the existing maneuver branches, but works to enable and support their traditional offensive and defensive characteristics. The lethality and agility of drones (especially in mass) dictate that drones move from the intelligence warfighting function to maneuver. It made sense only a few years ago to align drones under military intelligence when they were primarily intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms. Drones in their current multirole configurations, however, are more comparable in function to a main battle tank moving forward, engaging targets, positioning wingmen, and developing the situation. Sensing is now potentially only one aspect of a drone. Maneuvering air and ground drones and planning their effects follows along the same lines as doing so with infantry and maneuver formations. Drones require a maneuver mindset.

Third, recruiting for the branch should focus initially on maneuver and intelligence officers and noncommissioned officers. In the longer term, public awareness of—and interest in—drones means that the creation of a drone corps could increase overall recruiting and retention.

Fourth, the drone corps operates within maneuver formations or in drone-specific units.

And fifth, the drone branch is not a subset of the aviation branch, but works in concert with it to deconflict and simplify airspace management. Drones now operate across all domains, well beyond the air littoral where they were once almost exclusively found.

A Tactical Formation, Not a Niche Specialty

There are ways of meeting the letter of the draft NDAA language while stopping short of establishing a drone corps—simply creating the branch, for example, by changing the military occupational specialty of a few soldiers in maneuver formations. This would be similar to some of the Army’s lower-density military occupational specialties, like electronic warfare. The easiest path would be to rebranch soldiers in formations like the human-machine integration platoons. Individual subject-matter experts might be gathered on select headquarters staffs where other small-density specialties are consolidated. Maneuver companies would maintain organic drones to provide local situational awareness and strike capabilities. These operators could be either soldiers designated by the new drone military occupational specialty or additional-duty operators. Focusing drones only at the maneuver battalions is limiting the true potential of drones.

This simple and straightforward course of action, however, would not help with the imperatives of standardization and training. Moreover, the Army would be missing an opportunity to build a small lethal, formation that can enable other maneuver units or operate itself as a unit of action. Expanding task organization for drone use is the true spirit of the NDAA’s draft language.

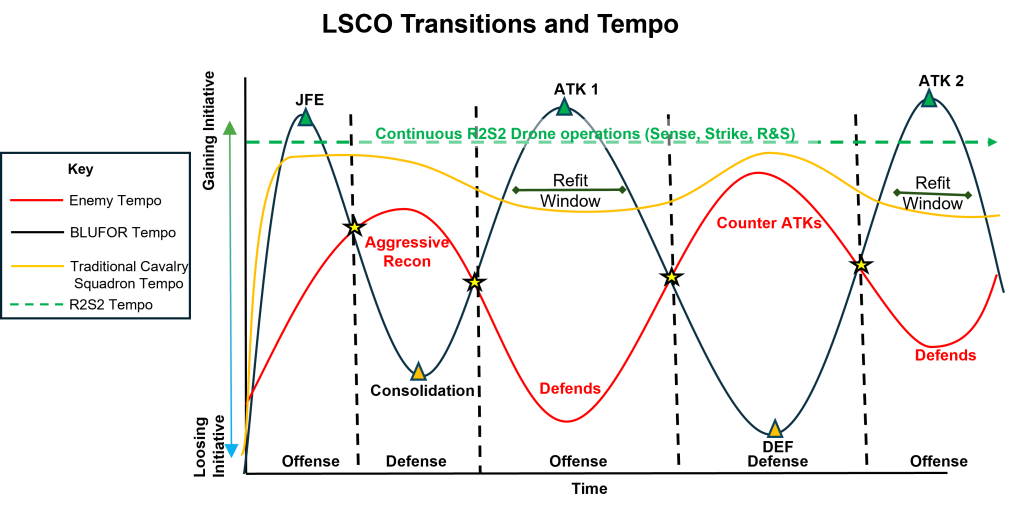

As an Army we are at a critical inflection point and have an opportunity to build a lethal enabling force. A more expansive course of action would involve creating drone units that can operate independently or augment brigade formations to fully leverage the situational awareness and strike capability of the systems. In a zero-growth environment with no major budgetary reallocations, the ready solution is the consolidation of the human-machine integration platoons across a division to build a robotics recon strike squadron (R2S2). An additional manning solution could incorporate the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance company in the intelligence and electronic warfare battalion. An R2S2 would be small formation task-organized under a division headquarters, commanded by a lieutenant colonel.

There would be two primary missions of the R2S2. The first is to standardize training, maintenance, and equipping across a division, ensuring that the additional-duty operators within maneuver formations are proficient. This would be similar to a DIVARTY (division artillery) concept, and in fact the fires enterprise more broadly is an excellent model for a drone crops. Fires professionals in maneuver battalions, brigades, and separate fires battalions ensure that the warfighting function is appropriately trained and leveraged.

The second mission is to deploy human-machine integration platoons or companies in front of or supporting maneuver battalions to conduct targeting and reconnaissance and surveillance operations for supported brigades or divisions. This provides an economy-of-force element that creates decision space for commanders at echelon.

An R2S2 assigned to a division headquarters would be uniquely positioned to sense with robots, coordinate the intelligence picture with the adjacent intelligence and electronic warfare battalion, and strike with division, corps, and joint assets. More importantly, establishing a headquarters to manage the data provided by drones in all domains ensures that critical data can be translated into intelligence requirements or strikes. This headquarters would close a critical gap created with the deactivation of traditional cavalry squadrons. US Navy senior leaders in the Indo-Pacific region have advanced a vision, which they describe as a “hellscape” and which acknowledges drones’ rapid economy-of-force potential to their ability to provide time and space for the joint force commander in the event of a Chinese incursion into Taiwan. An R2S2 would provide the Army with a deployable land- and air-based “hellscape” option at the next conflict zone.

The R2S2 does not need to be a large formation and should leverage other sustainment functions within division headquarters formations to reduce overall manning requirements. For example, the R2S2 could receive routine S-1 or S-4 support from the established headquarters battalion, intelligence and electronic warfare battalion, or DIVARTY. The R2S2 headquarters should be designed to focus primarily on sensing and striking for supported divisions or brigades. Human-machine integration platoons and companies within the RS2 would be equipped with infantry squad vehicles, multiple drones, and secure but unclassified communications systems to allow them to rapidly integrate and support maneuver battalions. A light package would ensure the platoons and the R2S2 can reposition or deploy quickly in support of economy-of-force missions and support to lodgments. Besides sense-and-strike missions, an R2S2 could also support mine emplacement and critical resupply operations for a division headquarters.

A third course of action would involve consolidating both human-machine integration platoons and battalion scouts under an R2S2 headquarters. This would further increase the reconnaissance and strike capability of the unit and ensure brigades and divisions have the best cued and mixed intelligence picture. It would provide a true all-weather sense-and-strike formation.

Completing the Kill Web

Establishment of a drone corps and R2S2 units would provide a key link in the Army’s evolving kill web. A well-positioned R2S2 with drones forward in all domains would establish a clear threat picture for a higher headquarters. While providing immediate kinetic effects with drone munitions, it would also provide strike recommendations and sensing for key shaping formations like multi-domain tasks forces and rocket battalions. Establishing subject-matter experts and utilizing the fire support model reduces cognitive load and training requirements for maneuver battalions. The training, maintenance, and use of drones within maneuver battalions are absolutely critical, but these activities come at the cost of time and distract from those battalions’ mission-essential tasks. Drone professionals and a focused R2S2 headquarters would ensure drones and operators are ready when needed. Having an R2S2 look forward while a brigade or division deploys or transitions would ensure that tempo is maintained. One can find multiple examples of Russian armored and infantry attacks being disrupted and destroyed by waves of drones with minimal or no friendly maneuver support. Pairing the use of drones with a combined arms mentality of the US Army increases overall lethality and maximizes drone effects. An R2S2 would also provide a continuous layered and joint defense, as well as a sense-and-strike capability for a division.

In short, the R2S2 would provide a small drone–focused package to tie together the Army’s kill web. Small and agile units would move and hide on the battlefield while pushing drones forward. Equipped with one-way drones and linked to the fires network, an R2S2 would punch above its weight and buy time for a higher headquarters.

The Next Evolutional Step

New weapons and platforms routinely drive change in the character of warfare. The introduction of tanks and planes came with great consternation as to how they should be used. The incorporation of drones is no different: they are a powerful asset that must be managed by dedicated professionals, similar to fires and aviation branches. The drone corps, even if established with a built-in R2S2 concept, is not the final step, but the first in a continual process of improvement and transformation. In a resource- and personnel-constrained environment, the Army cannot afford to mismanage its drone force. It must fundamentally reconceptualize what it considers maneuver branches, and how it organizes and fights maneuver formations. Drones will remain a major feature of the near-future battlefield. To be prepared for that battlefield, the Army needs a drone corps and its subject-matter expertise.

Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Suthoff recently served as the commander of 3-4 Cavalry. He resides in Colorado with his wife and five children.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Brahim Douglas, US Army