Part one of this two-part series described several ways that the National Training Center (NTC) is adapting to preliminary lessons from the war in Ukraine. From the technology-driven transparency of the modern battlefield and increased mass precision strikes to synchronization above the brigade level and the fight for the narrative, each rotational training unit is confronted with some of the most important features on display in Ukraine. This second installment offers six recommendations to unit commanders as they prepare for an NTC rotation—and for an uncertain future on the battlefield we seek to replicate. These recommendations are by no means conclusive but focus on those specific adaptations that are changing the operational environment at NTC.

1. Understand and train for the operational environment you will face.

Effective units at NTC invest considerable intellectual effort, often months ahead of time, to visualize how they will fight their organization in this operational environment. NTC welcomes unit leader visits, ride-alongs with the opposing force (OPFOR), and home-station leader professional development sessions from our observer coach-trainer teams. Best practices and lessons learned are shared by the NTC operations group staff in the form of podcasts and a new series of video “TAC Talks” now available on YouTube. The Training and Doctrine Command G2 also includes a wealth of resources and briefings on initial observations from the conflict in Ukraine. Studying and discussing these within a unit will equip that unit with an understanding of its future operational environment that will directly benefit it during an NTC rotation.

Great units take this intellectual effort one step further and build robust tactical standard operating procedures (TACSOPs) that are detailed, widely distributed, and integrated into their planning and orders process. Complex topics like command post designs, orders formats, precombat inspection checklists, and rehearsal scripts are already worked out in the unit TACSOP and clearly understood. Units that have clear standards for these complex tasks also tend to empower their noncommissioned officers much more effectively during the rotation because standards are widely known and commonly enforced.

2. Build agile command posts that can operate across the threat spectrum.

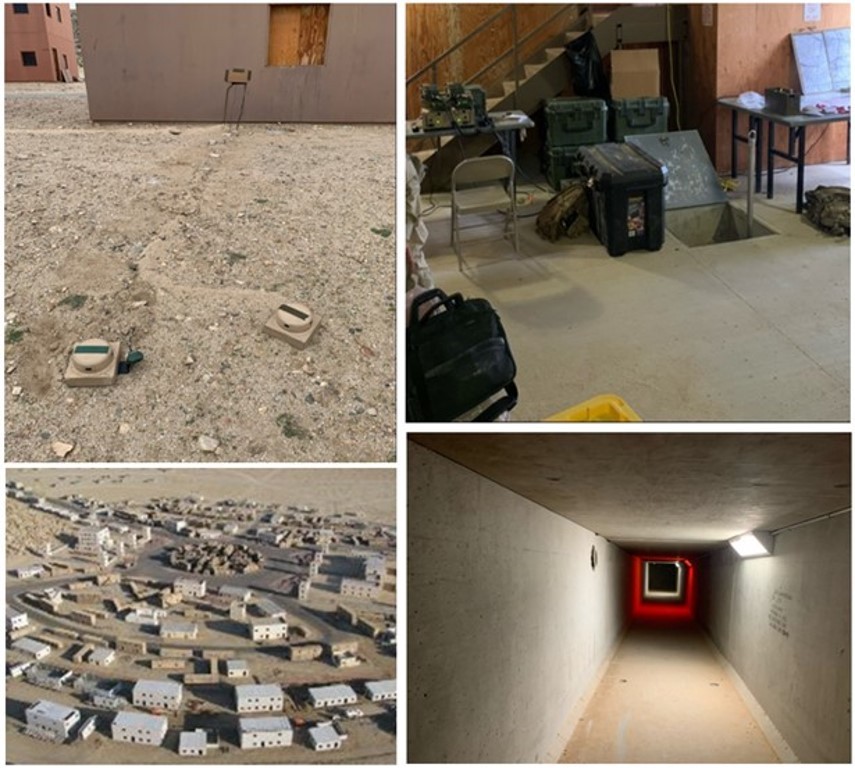

The Army is working to design and field a command post that is both effective and survivable. In the interim, today’s commanders are often left with the unenviable choice between survivability and capability. Effective units understand this dilemma and develop an agile command post structure that can adapt from a highly capable configuration that might be appropriate for a low-threat area distant from accurate enemy fires to a much more survivable and dispersed configuration when conditions warrant.

Like the mission-oriented protective posture used to regulate protection against chemical threats, the 52nd Infantry Division—the higher headquarters for each rotational training unit—publishes a daily command post threat posture that moves between permissive, low, medium, and high throughout the course of the rotation. Effective brigade combat teams can adapt to this escalating threat by offloading some command post capability at an over-the-horizon location while preserving what they need forward in a survivable footprint. This allows them to take full advantage of a stable upper tactical internet and reliable access to the large amount of national-level data from signals, imagery, and open-source intelligence that can produce real-time, actionable information for battalion and company commanders. Each unit that adopts this practice quickly finds that its rear command post has an exceptionally rich picture of the enemy situation but only a vague understanding of friendly actions and cannot distill data into information that is both timely and relevant to the unit in the fight.

Training at home station is critical to ensure a unit has both an agile command post forward in the close fight and a relevant command post postured over the horizon. Units should also rehearse occupation of suitable urban terrain in a credible way where vehicles are positioned far from occupied buildings, critical capabilities are covered from overhead view, antennas are masked, and personnel movement outdoors is tightly controlled to prevent detection.

3. Build a stable and reliable network that can maneuver with the brigade combat team.

Clausewitz reminds us that everything in warfare is simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. Nowhere is this aphorism truer than in the creation and preservation of a stable communications network across a brigade combat team on the move. Over the last twenty brigade rotations at NTC, the number one reason for a brigade commander to culminate offensive operations and transition to a defense is not a lack of fuel or ammunition or even the loss of combat power. It is the inability to communicate reliably as the brigade stretches over extended distances and intervening terrain. Upper tactical internet systems degrade quickly after the first few command post jumps, retransmission sites fail due to poor placement and limited ability to troubleshoot minor faults by isolated operators, and Joint Battle Command–Platform systems degrade quickly due to poor maintenance and improper shutdown procedures.

Effective units mitigate these risks by investing heavily in communications training prior to deployment. Division G6 personnel should conduct detailed inspections of server stacks and satellite configurations. In the most optimal cases a reliable upper tactical internet can enable the brigade commander to position significant analytical capability from the brigade combat team command post over the horizon, well outside of enemy threat, while remaining connected with the command post forward. Certified communication experts within the brigade must validate retransmission capabilities at home station using the gated training strategy in Training Circular 6-02.1 and actively support critical retransmission planning throughout course-of-action development with robust technical analysis. Finally, Joint Battle Command–Platform systems must be prioritized during unit maintenance and tracked on the unit equipment status report.

4. Develop and rehearse a fires kill chain that moves at the speed of war.

Outdated manual methods of fires processing are generally irrelevant to the future fight. Both Ukrainian and Russian forces have demonstrated artillery response times that consistently run less than three minutes. Dynamic fires slower than this are not relevant to the fight and only perpetuate outdated practices. The 52nd Infantry Division requires the brigade combat team to target and destroy enemy forces, to include artillery and mortars between it and the brigade’s forward boundary. This allows the division counter-fire headquarters to focus on the more serious division deep fight against enemy rockets, air defense, and long-range artillery. Effective units at NTC have developed and rehearsed unit tactics, techniques, and procedures that clearly assign decision authority and responsibility to find, fix, and finish enemy threats detected in accordance with the commander’s essential fire support tasks. This process is too complex to first establish in crisis and should be an integral part of unit training.

5. Train units to operate dispersed, masked, and mobile.

Home-station training must emphasize the fundamental reality that the concentration of vehicles draws enemy artillery. Distance from the enemy and distance from each other saves lives. Commanders in any static location must remain continuously conscious of their electronic signatures and seek ways to mask those signatures below the floor of ambient electromagnetic spectrum noise. Looking unimportant also saves lives. Unique features of any high-value capability should be carefully concealed, where possible, so that an adversary struggles to discern the critical from the routine. Finally, units should train to move regularly and in small groups as a part of normal practice, especially at dawn and dusk, to avoid detection.

Culturally, this is incredibly hard for an Army whose lived experience has been in dense, stationary, forward operating bases enclosed behind concrete T-walls and razor wire. A recent encounter, during battlefield circulation by the operations group leadership, with an understandingly frustrated and heavily sleep-deprived major offers an indicator of how difficult this cultural change is. His command post had just received over one hundred rounds of accurate 152-millimeter fire from the OPFOR. Recognizing that more strikes were imminent he was reluctant to jump what remained of the command post due to ongoing activity. When I asked if he ever received incoming artillery in combat, he commented that mortar strikes were a near daily occurrence during his last tour in Iraq but that he “never jumped the FOB [forward operating base].” For too many of us, our personal experience with artillery has been as a nuisance rather than an existential threat to our units and our missions. It will take significant work and leader engagement to change this view.

6. Make field sustainment a routine part of home station training.

After command and control, challenges with sustainment over distance account for the greatest limitations in unit performance at the National Training Center. Great units plan for tactical sustainment at NTC by incorporating it into every facet of home-station field training. Brigade support battalions deploy to the field with forward support companies attached so that they can rehearse field trains operations and establish a fully functional brigade support area. The brigade’s common authorized stockage list also deploys at home station to provide valuable practice in sustainment operations from a field location. Great units also conduct disciplined logistics release points twice daily for all field training exercises so that their company first sergeants and battalion S4s build practice and discipline delivering all supplies, including Class IX repair parts, on regularly scheduled logistics packages. Logistics status reports are submitted daily at home-station training exercises as well.

Each rotation, the operations group compares similar equipment fleets of similar age against each other, and we see significant difference in readiness rates between companies. Time and again, the difference comes down to unit culture and maintenance discipline. Great units operate on explicit priorities of work that place preventative maintenance at the top of the list. Crews are trained how to inspect and lubricate suspension systems or how to manage electrical power in their vehicles to prevent damage. These simple skill sets backed up by routine inspection by knowledgeable small-unit leaders make the difference and quite often are the key to a brigade’s ability to sustain continuous operations over two weeks.

The National Training Center is adapting rapidly to keep pace with emerging lessons from current conflicts. Achieving success on the complex modern battlefield is a challenging endeavor, but units that understand and implement the recommendations described in this article will enhance their readiness for this new environment. An ability to adapt to the evolving environment, however, must be layered on top of a strong foundation because, ultimately, the fundamentals of what makes a successful rotation here at NTC have not changed. Great units succeed at the National Training Center because they have a cohesive culture founded on discipline and warfighting readiness. They prioritize mastery of the fundamentals at home station and empower their noncommissioned officers through effective training management. This remains the bedrock of training excellence today and will do so as we continue to adapt in the future.

Major General Curt Taylor has commanded the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California since April 2021. This is his third assignment at a combat training center, having served as an observer coach-trainer as a captain and a lieutenant colonel. Prior to taking command of NTC, Taylor activated and deployed the 5th Security Force Assistance Brigade in training operations with allies and partners across the Indo-Pacific region. Additionally, he commanded a Stryker brigade at NTC in 2017 and deployed an Armor battalion to Afghanistan in 2012.

Special thanks to Captain Joe Davey for his assistance with and editing of this article. The secretary of the general staff for the National Training Center and Fort Irwin since May 2023, Captain Davey previously served as an observer coach-trainer on the Cobra Team as a part of Operations Group. Prior to his assignments at Fort Irwin, he served as the commander for Apache Troop and later Hatchet Troop in 2-13 CAV, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Daymeon Evans, US Army