Great power competition has become a popular topic in defense circles—and that’s putting it mildly. The National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy both address it, events are held to discuss it, and the phrase may even be so popular that it becomes a cliche. Despite this focus, very little literature about the topic addresses a closely related and pressing issue (especially given the prospect of competition between great powers becoming conflict between great powers): the United States’ ability to quickly generate trained personnel to replace field losses during high-intensity conflicts. As long as this remains unaddressed, the United States will struggle to understand the limitations of its conventional military power in protracted wars.

If the United States needed to, it could almost certainly put one million new soldiers under arms. The issue here is not the ability to draft a large number of people; it’s the draft’s inability to train and deploy soldiers quickly enough to preserve strategic and operational advantages in a peer conflict. The best way to understand this issue is through a thought experiment. What follows is not a predictive model. It is a tool to help explain the implications of the military’s force structure and the Selective Service System’s policies. For simplicity’s sake, it will only address Army personnel.

Thought Experiment: Is the Selective Service System Ready for Great Power Conflict?

Background

The most likely scenario for a draft is a great power war. Many pundits today argue that nuclear weapons, economic entanglement, and other factors mean that any great power war will be short. However, earlier this year, the Center for a New American Security published “Protracted Great-Power War: A Preliminary Assessment.” In it, Dr. Andrew Krepinevich argues that there are contingencies in which nuclear-armed combatants will impose constraints on vertical escalation even while remaining committed enough to continue fighting a high-intensity conflict for an extended period.

The United States fought two great power wars against peer adversaries in the twentieth century, World War I and World War II. Adversaries in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan did not have the same relative economic, technological, or military capabilities, and therefore do not meet the criteria for great power conflict. During World War I, 106,378 American soldiers died and 193,663 suffered non-fatal wounds over the fifty-four weeks between the start and finish of US combat operations. During World War II, 318,274 American soldiers died and 565,861 suffered non-fatal wounds during 191 weeks between the beginning and end of combat operations. If it is assumed based on trends from World War II that only 20 percent of treated, wounds were able to return to duty, the United States averaged a loss of 4,213 soldiers per week during protracted great power wars against peer rivals.

Congress authorizes the Army an end strength of 478,000 Regular Army, 189,250 Army Reserve, and 335,500 Army National Guard soldiers. This force has thirty-one active duty and National Guard brigade combat teams (BCTs) composed of 480,000 soldiers. The rest of the Army’s manpower is assigned to the institutional Army, such as schools, as well as functional and multifunctional brigades.

Scenario

Consider a scenario in which the United States is fighting a major, non-nuclear, protracted war against a great power adversary. As noted above, Dr. Krepinevich argues this to be both politically and strategically feasible. Assume the United States will lose thirty thousand soldiers before military and political leaders decide the Army will not be able to continue to meet its operational requirements with its existing force structure. Once the government has that realization, it could turn to the Selective Service System.

Timeline

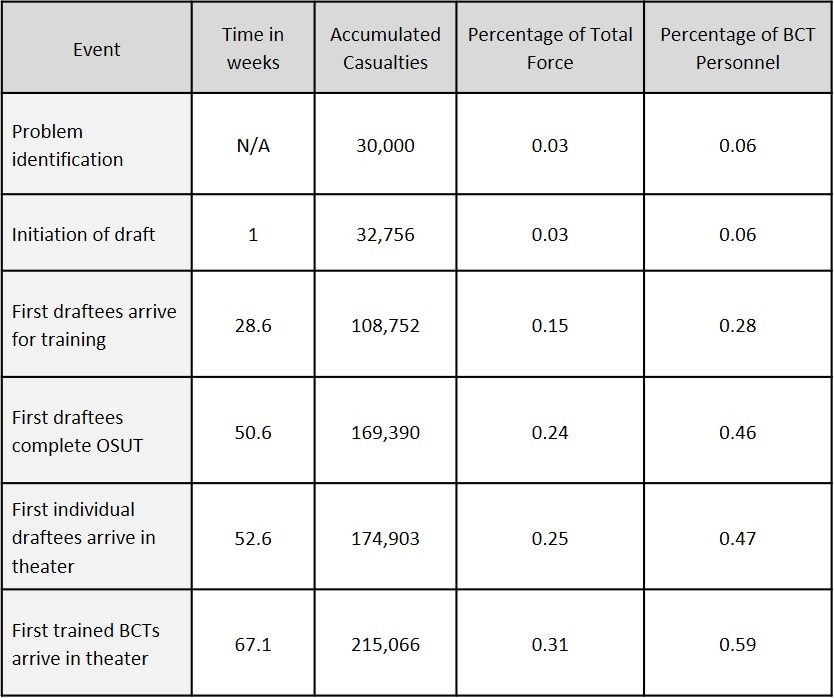

To initiate a draft, Congress needs to amend the Military Selective Service Act. It is unlikely that doing so would be popular among the American people. Richard Kohn, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who studies war and the military, has described any move to reinstate the draft as likely to be “one of the most unpopular proposals presented to the Congress in many years.” Assume it would take one week for a hypothetical Congress to authorize and a hypothetical president to initiate a draft. Once this takes place, the Selective Service System is required to deliver the first inductees to the military for training within 193 days of its activation, or 27.5 weeks.

The inductees’ next step would be basic training. Drafts have historically been used to create large numbers of infantry soldiers. Today, the US Army’s infantry training, or one-station unit training, lasts twenty-two weeks. It is reasonable to assume that it would take an additional two weeks for newly drafted soldiers to begin arriving in theater to fight. If the above timeline holds true, it would take 368 days—just over one year—from the time military and political leaders realize the US Army’s force structure is insufficient to meet a conflict’s demands for the first draftees to arrive in theater.

Moreover, that process is unlikely to create an Army as capable as our current all-volunteer force. For the last several decades, the Army has avoided using an individual replacement system. Instead, it prefers to use a unit replacement system, typically by deploying full BCTs. Soldiers need to learn to work together, both to build cohesion and to learn the intricacies of operations that cannot be learned as individuals. The unit replacement system is premised on an acknowledgement that s company’s worth of individuals is not a replacement for a company that has trained together.

The Army could mitigate this concern by taking the time to train and build units to send overseas together. Officers and NCOs serving in the institutional Army and in security force assistance brigades could be used to form the leadership of new BCTs, which could be filled in by draftees and trained as units. One approximation for the time required to train new brigades comes from a RAND study that estimates it will take 102 days to train a National Guard brigade before deploying it overseas. This would improve the combat effectiveness of replacements, but extends the timeline further, to a total of 470 days.

On top of the initial loss of thirty thousand casualties that we estimated would precede military and political leaders’ determination that the Army’s force structure was insufficient to meet its combat requirements, there are now 4,213 casualties a week that do not return to duty. The Army would have lost 251,502 soldiers by the time individual replacements would arrive in theater. If the Army decides to instead send trained brigades instead of individuals, that figure rises to 312,896. Those projections represent 25 percent and 31 percent, respectively, of the Army’s 2019 total authorized end strength of 1,002,750. If 90 percent of the casualties are from the 480,000 soldiers in BCTs—not an unrealistic assumption—the percentage changes to 47 percent and 59 percent of active- and reserve-component soldiers in BCTs lost. According to the Joint Staff’s Methodology for Combat Assessment, military units are severely attrited when they lose 30 percent of their personnel or equipment. In this thought experiment, the average BCT would be severely attrited before the first draftees complete one-station unit training, much less arrive in theater or participate in BCT training, and the entire Army would be severely attrited before the first trained BCTs would arrive in theater.

Importantly, there are other considerations that could reasonably be expected to make this situation even worse:

- The scenario assumes the casualty-producing conflict is the Army’s only commitment, allowing it to concentrate all active- and reserve-component soldiers. This carries with it a related assumption that the Army will not need to defend the homeland, continue to carry out existing overseas obligations, or fulfill new deterrence requirements to prevent other conflicts from flaring up.

- The thought experiment assumes the Selective Service System will be able to meet its 193-day timeline. The system faces a monumental task executed by an unproven team spread across the country. It relies on the military’s medical system to screen potential draftees, which may be challenging. In the case of a great power conflict, it is also probable that the homeland will be under some form of attack that will hinder a draft.

- The thought experiment focused on infantry because drafts are historically used to generate large infantry formations, and because most combat casualties are infantry soldiers. There are also servicemembers in other jobs who are likely to see a significant number of casualties in the event of a great power conflict, but who require more training. Air Force fighter pilots go through a forty-day Initial Flight Screening, twelve months at Specialized Undergraduate Pilot Training, five months at Introduction to Fighter Fundamentals, and six to eight months at a Formal Training Unit. In total, draftees who attends the Air Force’s Officer Training School and become fighter pilots experience twenty-four to twenty-six months of training before they arrive at an operational unit. Similarly, enlisted nuclear submariners go to basic training for seven to nine weeks, “A” School for three to six months, Naval Nuclear Power School for six months, and finally a Nuclear Power Training Unit for six months. In total, it takes the Navy sixteen to twenty months to create a nuclear submariner.

Reasonable people can disagree about the validity and importance of these assumptions—after all, certain steps could be taken that might adjust the timeline to some limited degree. But even so, the conclusion is unavoidable: with its current force structure, if the United States fights in a protracted, great power war that follows historical trends, the Army’s combat forces will be severely attrited before draftees arrive in theater.

Possible Solutions: Ends, Ways, and Means

Changing Means

The most interesting recommendation for changes to the Selective Service System come from Dr. Krepinevich’s colleagues at the Center for a New American Security, Elsa Kania and Emma Moore. They argue that the system should include a mechanism for individuals to register to mobilize quickly and deploy to front-line units if a draft is initiated. However, it is unclear how many people might be interested in volunteering for front-line service or how quickly it would take place compared to current timelines.

The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service makes a similar suggestion, arguing that the United States should recognize a “national mobilization continuum.” Under this proposal, rather than beginning national mobilization with a draft, the president would officially call for Americans to voluntarily join the military. While this recommendation has value, particularly in reducing the 193-day delay before draftees arrive for training, it would also delay the initiation of a draft, increasing casualties before draftees arrive.

The military might also use an abbreviated training cycle. The thought experiment assumes draftees will complete the current, twenty-two-week one-station unit training that enlisted infantry soldiers currently undergo. This training was only fourteen weeks long for forty years though, so it is feasible that infantry training could be condensed. Basic Combat Training, the common training that soldiers receive prior to attending their specialty-specific training, is roughly ten weeks long.

Political leaders might also initiate a draft earlier. The thought experiment assumes that political leaders would not decide to initiate a draft until the Army incurred 34,213 casualties that did not return to duty. Political leaders might instead, anticipating the demands of a protracted, great power war, initiate a draft at the same time as they either declare war or authorize the use of military force.

These changes would come at a cost, however. The Army increased the amount of training for its infantry soldiers because its previous fourteen-week schedule did not produce soldiers sufficiently well trained and physically fit to perform well in line units, much less in a high-intensity conflict. This problem is only likely to increase for draftees. Today, 71 percent of young people are ineligible to join the military due to health issues, education, and criminal records. If those standards are reduced or waived, at least some previously ineligible personnel are likely to need more preparation than today’s volunteers, especially when the increasing technical sophistication of current weapon systems is taken into account.

Changing Ends

If the United States cannot change the number of military personnel available for combat operations during the initial phases of a great power war, it would need to consider changing its ends. This might mean limiting objectives more than is desired, either temporarily or permanently. During World War II, this might have included more delays to the invasion of Europe with an understanding that this might allow the Soviet Union to seize more territory, or an agreement to enter into negotiations with Berlin and Tokyo rather than demanding unconditional surrender.

Changing Ways

Similarly, the United States could change its strategic- and operational-level plans to rely more on the defense, or to attack enemies sequentially rather than simultaneously. Returning to the World War II example, this might have entailed further delaying operations in the Pacific to dedicate resources to the European theater, or establishing strong forward defenses with the aim of causing the Japanese and Germans to exhaust or attrit themselves trying to retake the terrain.

Another way to rely on ways rather than means to overcome this problem would be to substitute technology for people. The United States, in recent years, has preferred to use firepower and other types of technology to reduce risk to servicemembers. One of the third offset’s core concepts was to rely on technology to produce a qualitative advantage that reduces casualties and let a relatively small number of professional soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines defeat larger forces. While this is a laudable approach, it relies on an assumption that the United States can maintain advantageous technology asymmetries. That assumption is less certain today than it was a short time ago, and may be even less certain moving forward.

Accepting Risk

Changing the draft to enhance means may be impractical, relying on technological superiority to compensate for limited means with more effective ways may be unreliable, and the United States may not want to limit its ends to avoid enabling adversaries. The remaining option is to simply accept the risk that the United States may run out of combat forces if it fights in a protracted, great power conflict.

The American people and their leaders are right to be confident in their military and its abilities. But that confidence should be tempered by an understanding that great power conflicts have, in the past, required massive personnel commitments. Accepting risk or relying on technology, may be the best choices, but during great power conflicts they may have the potential to force the United States into scenarios without good choices. Is it possible that American combat units would be so severely attrited before draftees begin arriving in theater that the United States would be forced to either adjust political objectives or to use technology in a way that requires vertical escalation, the pinnacle of which is nuclear warfare? The above thought experiment shows that may be a potential outcome.

The United States has an important role to play in the world, and fulfilling it requires the ability to project power effectively in a variety of scenarios. The most extreme cases are protracted, great power conflict. Unfortunately, those conflicts and the casualties they produce are just as possible in the twenty-first century as they were in the twentieth. That requires us to ask difficult questions about whether the United States is prepared.

Justin Lynch served as an active-duty army officer before transitioning to the Army National Guard. As a civilian, he has served in multiple roles in the national security enterprise, and has written for Joint Force Quarterly, Modern War Institute, War on the Rocks, and several other national security journals.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Philip McTaggart, US Army