The reality of American military power has long been that the United States must project its forces into the enemy’s territory. This brings with it a host of challenges, some inflicted by the adversary and others that are self-inflicted (such as lack of strategic lift or production capacity). In any future war, the US military will likely play an “away game,” and an adversary will probably not allow the United States to leisurely amass personnel and equipment on its borders, but will actively try to prevent it. As a result, the US military will suffer from an inherent asymmetry and have immense costs imposed on it, at least in the initial phases of the war. This challenge lies at the heart of what is colloquially called the “anti-access/area denial” family of military concepts.

To solve the challenges associated with this inherent asymmetry, a range of ideas have emerged—Multi-Domain Operations from the US Army, distributed lethality from the US Navy, Joint All-Domain Command and Control from the US Air Force, “mosaic warfare” from DARPA, and various “sweeping changes” from the Marine Corps.

A review of the commonalities between these concepts, however, reveals inherent challenges in them—and as such, at the heart of American military thought.

So Say We All

The first item in common between virtually all American concepts is the perception of the threat and threat actors. Even if there are some disagreements on the margins about the details, the threat is perceived as a global or regional military power, employing a long-range, layered, defensive complex, that protects long-range “strategic” offensive capabilities. The specific offensive and defensive assets may vary according to the unique environment the adversary will operate in. But despite the different details of assessments of, for example, Russia and China, the basic idea of both powers is similar. They both aim to protect land-based strike assets that will be used to strike American military capabilities, seeking to complicate the American arrival to the area of interest and operations inside it once US forces have arrived.

Second, there is also a general agreement about ways to survive this threat. Because the US military assesses the adversarial anti-access/area denial system as essentially a long-range strike complex, the ability to find targets and relay their locations back to strike assets in real time (called a “kill chain”) is essential to the adversary. Disrupting that chain can drive a stake through the heart of the entire strike complex.

The third area of consensus is the solution to the challenge. The adversary presents a system that is assumed to be both lethal and resilient. The overlapping fields of fire, reaching hundreds of kilometers from the adversary’s territory, are presented sometimes as impenetrable bubbles. The solution is to avoid detection, penetrate those bubbles, and eliminate the adversary’s strike assets themselves and their supporting command, control, and intelligence infrastructure. In a way, the American answer to the adversary’s intelligence-strike complex is the creation of a competing intelligence-strike complex, which will be able to direct distributed forces and strike assets, to operate inside the adversary’s anti-access/area denial bubbles and dismantle them from the inside. Herein lie three main challenges.

Inside Out or Outside In

In many, if not all, future conflict scenarios the US military expects to start the war numerically inferior, and quite likely surprised. The United States can try to compensate for this disadvantage with technological superiority, although that advantage is eroding. And in any case, quantity has a quality all its own. It is thus fairly safe to assume that a significant portion of American forces will have to fight their way into the area of operations, while the residual forward-positioned forces, possibly cut off from reachback support, will fight a defensive battle, or even a retrograde, against numerically superior forces.

The forces coming in will have to punch their way through the adversary’s defensive complex, possibly partially blind to what is going on inside those perimeters. Since the range of current defensive capabilities is longer than that of many American strike assets, the US military will have to use standoff munitions and small numbers of penetrating platforms. This approach is fighting “from the outside in.”

However, in the various concepts mentioned above, it is generally agreed that the best way to disintegrate the adversary’s defensive bubbles is by maneuvering inside them, obtaining real-time intelligence about defensive and offensive assets, and attacking them rapidly. This is fighting “from the inside out,” mostly with short-range weapons by what the Marine Corps calls “stand-in forces.” Since the United States will probably not have sufficient forces to perform large-scale operations with these forces in the initial phase of the war, there is a constant tension between the goal of achieving a sufficient stand-in presence to have an impact and the rather safe assumption that the war might start while the US is mostly in a standoff position. This is a gap that neither the Army’s concept nor the Marine Corps’ planning guidance elaborates on how to bridge. Both, as well as the National Defense Strategy, mention forward-positioned forces, but it is understood that those will never be enough. The answer that is presented is heavily investing in standoff fires capabilities and penetrating platform, so as to create a lethal intelligence-strike complex, or what amounts to a reverse anti-access/area denial system.

The Away Team’s Challenge

The assumption is that these reverse anti-access/area denial capabilities might be able to bring enough high explosives to enough targets to either punch a hole in opposing defenses or cause the adversary, somehow, to surrender. This assumption, however, ignores the key asymmetry between American forces and their adversaries. The Americans, as mentioned above, have to play an away game. That means they have to bring their forces and their supplies from the United States, or other remote locations, to wherever they are fighting. Despite attempts to somehow avoid the “iron mountain” of supplies, there is no way of hoping away physics. Vehicles require fuel, people require food, and munitions require replenishment. Eventually, prepositioned supplies and forces will run out, and the American war effort will require aerial and naval assets both for fighting as well as for transportation—assets that are, by definition, lucrative targets.

The adversary, on the other hand, is fighting on or from land—and critically, on or close to the adversary’s own territory. That enables the use of land platforms both for transport and for fighting. Land platforms are smaller, cheaper, simpler to produce, and far more numerous than their air and naval equivalents. Also, the land domain, with its mountains, valleys, and trees, is easier to hide in than the empty air and open seas. Furthermore, the land domain allows a defender dig in, and thus protect essential supplies, platforms, and nodes of command and control. Thus, China can fire tens of multi-million-dollar missiles at a nuclear aircraft carrier. Once this carrier is hit, it might take years to replace and will subtract substantial portion of American strike capabilities for a duration of time, especially at the outset of the war. On the other hand, mainland China has hundreds of thousands of targets. Very few of them are as strategic as an aircraft carrier. Those that China deems strategically vital are probably well dug in and thus physically hard to destroy and many of the rest are cheaper and more replaceable than even the munitions fired at them.

Even assuming away the friction of war, the United States might not have enough munitions to strike so many targets—and smart munitions, even the simple ones, require more resources to develop and produce. That means the US military can’t win a salvo war. However, its adversaries can.

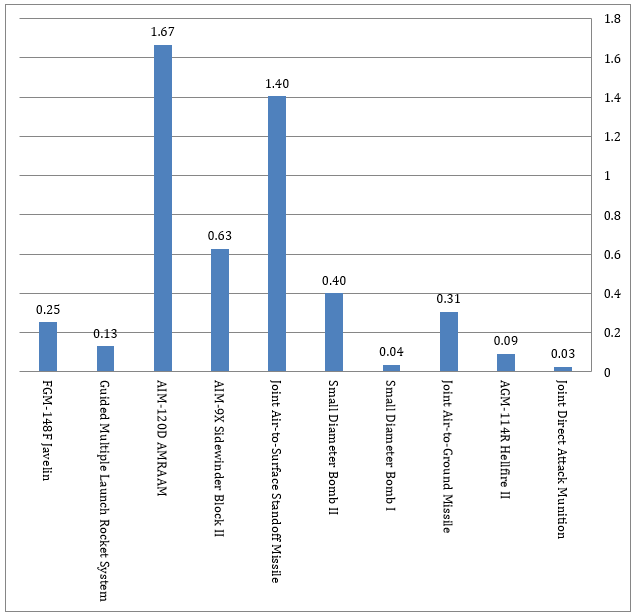

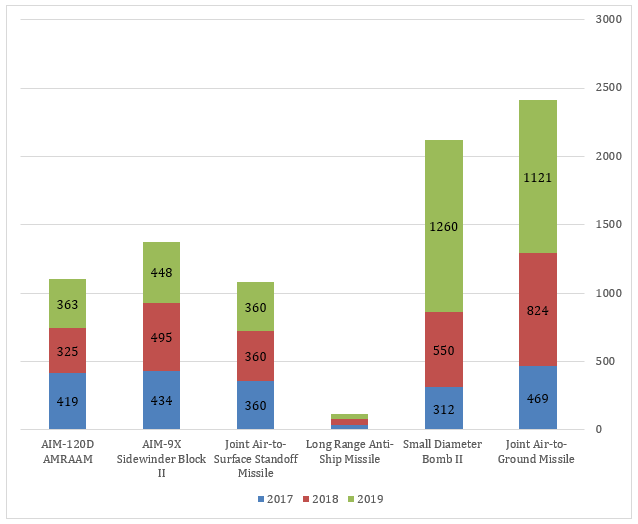

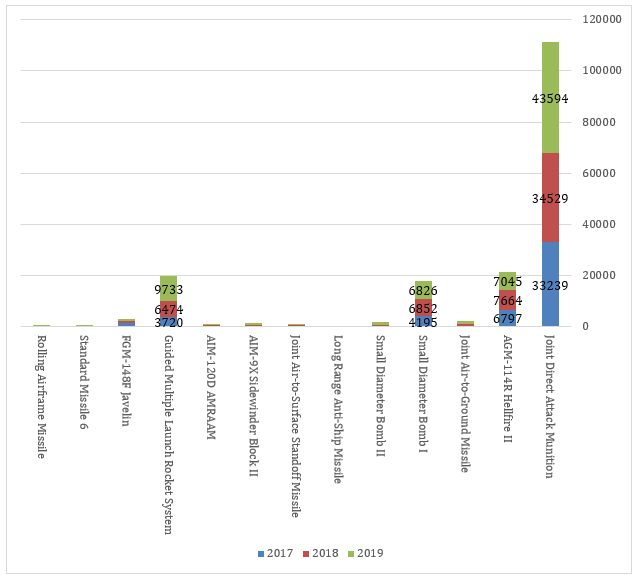

Numbers of munitions purchased, FY 2017–2019 (see next figure for further detail)

War is More than Striking Targets

This leads to another, larger, asymmetry between the United States and its adversaries. A look at current wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, as well as past wars such as Vietnam and World War II demonstrates how incredibly resilient a nation-state can be. History gives the lie to “effects-based operations” concepts that assume an enemy can be brought to its knees with a few targeted strikes on key nodes in its system. A nation-state with many millions of people can withstand years of war and hundreds of thousands of casualties and keep fighting.

However, the so-called revolution in military affairs that captured many defense thinkers’ minds in the late twentieth century did change something significant in military forces—or at least in Western military forces. It made them harder to replace. If in the past a national economy could be mobilized to produce hundreds of thousands of planes, tanks, and ships, today mobilization is far harder, and weapons are far costlier and take longer to produce.

A Western military could, theoretically, be broken by attrition—at least long enough for its adversary to establish facts on the ground. This is the other side’s concept of victory. The goal is to deny an adversary’s will or ability to fight on at least one (or more) levels of war. A concept of victory is unique to the opponent and is a function of its unique nature, environment, and circumstances. There are two important items to note about a concept of victory: one, it can be hard to imitate that of an adversary; and two, a concept of victory that is relevant against a certain foe might not be transferable to a different adversary.

A New Way of War, Inspired by the Past

The United States is not the first power to face this challenge. Before the age of American hegemony, it was Great Britain who ruled interests the sun never set on. The British faced the reality of not having a foothold on the continent where it considered its core interests to lie since the fall of the Pale of Calais. Britain had to compete globally with France, as well as on the European level with regional, smaller powers such as Austria, Russia, Spain and later, Prussia. At the height of its success, the Great Britain had a very distinct way of managing its interests. To execute its wars, Britain had replaceable European partners who conducted most of the warfighting on land. Meanwhile, Britain itself funded these wars, supported European partners with strategic lift, and secured the seas—while advancing British interests throughout the world under the cover of the war in Europe. While supporting its European partners, Britain simultaneously conducted its own global fight against its main rival, France.

The key to Britain’s power was not domination of the entire spectrum of conflict in all domains, but rather its economic might, backed by superiority in a single (naval) domain and its diplomatic ability to always find competent partners—at least militarily. Also, Britain chose to conduct limited wars. The goal, after the Hundred Years’ War, wasn’t taking over the thrones or changing the regimes or religions of any other European power, but rather to balance power in Europe and take control of colonies and other economic interests outside of Europe. Thus, war could always end with negotiations, without dire defeats and complete victories.

In a way, this represents a model. The United States doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. It just needs to rediscover it.

The ways to overcome the gaps in American military thinking mentioned above are twofold—tactical and strategic.

On the tactical level, the only way for the United States to overcome the standoff/stand-in gap is to use forces that are already inside the area of operations. These forces can never be entirely, or even mostly, American. They should overwhelmingly belong to host nations that border the powers the US military might fight against. The United States is fortunate to have a network of rich nations as allies. These nations could sustain vast militaries, at an affordable price, especially if their forces are organized for defense and operations close to their borders.

For that matter, the United States has little use of mid-sized nations that pay a premium for expeditionary, high-tech capabilities. It should encourage its allies to build forces that can withstand war in their area instead. Meanwhile, the United States should play a mostly supporting role, in the global theater—at least in the beginning of the war. It should help fund and regenerate forces, secure the global commons that support its allies’ wartime economies, and employ strategic enablers such as airpower, strategic intelligence collection, and, of course, the ultimate guarantee of the nuclear umbrella. When the United States fights outside its adversaries’ backyards, those adversaries will be forced to use expeditionary capabilities and pay the same premium Americans pay for their capabilities, but with far smaller budgets to sustain it. Thus, the concept of victory for the United States should be for partners to achieve tactical victory while the US military pursues operational victory—ultimately achieving strategic victory.

But this tactical solution will be for naught if the United States does not match it with another reform on the strategic level—abandoning the concept of total wars. The short era of fighting a great power, or even a medium power, to submission has passed. There is little chance that any combination of European countries can conquer Moscow or totally defeat China—at least without nuclear weapons. The time between the Napoleonic Wars and World War II was unique, in that societies were small and rural enough to subdue, yet large, young, rich, and productive enough to support large-scale mobilization, absorb casualties, and pursue conquests. Even assuming some kind of land maneuver in Russia or China is possible, there is the added factor of global urbanization. A modern megacity is a military nut no one knows how to crack. If the battle for Mosul is any indication, there is no military large enough to take over a single mid-sized city in China, let alone the entire state. Bombing it to submission, will probably not do either.

So what is left is to fight on the periphery—on islands, waterways, and bases far from the mainland or motherland, and often for interests far from them, as well. Incidentally, these are also interests that can later be negotiated over, as opposed to the survival of the nation or the regime.

These two suggestions are a continuation, in a way, of British military thought at the height of the island nation’s global power—fighting limited wars with partners. It seems that the world is slowly reverting to its pre-modern form—a big and fragile Russia, a strong China, and wealth that is flowing on the world’s commons, with no power willing or able to annihilate the other. In this world, concepts developed for an era of unipolar supremacy will not do.

Shmuel Shmuel is the director of the Institute for Military Studies at the Israel Defense Forces’ Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies. Follow him on Twitter @Samdavaham.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or those of the IDF or the Dado Center.

Image credit: Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kaila V. Peters, US Navy