Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”)

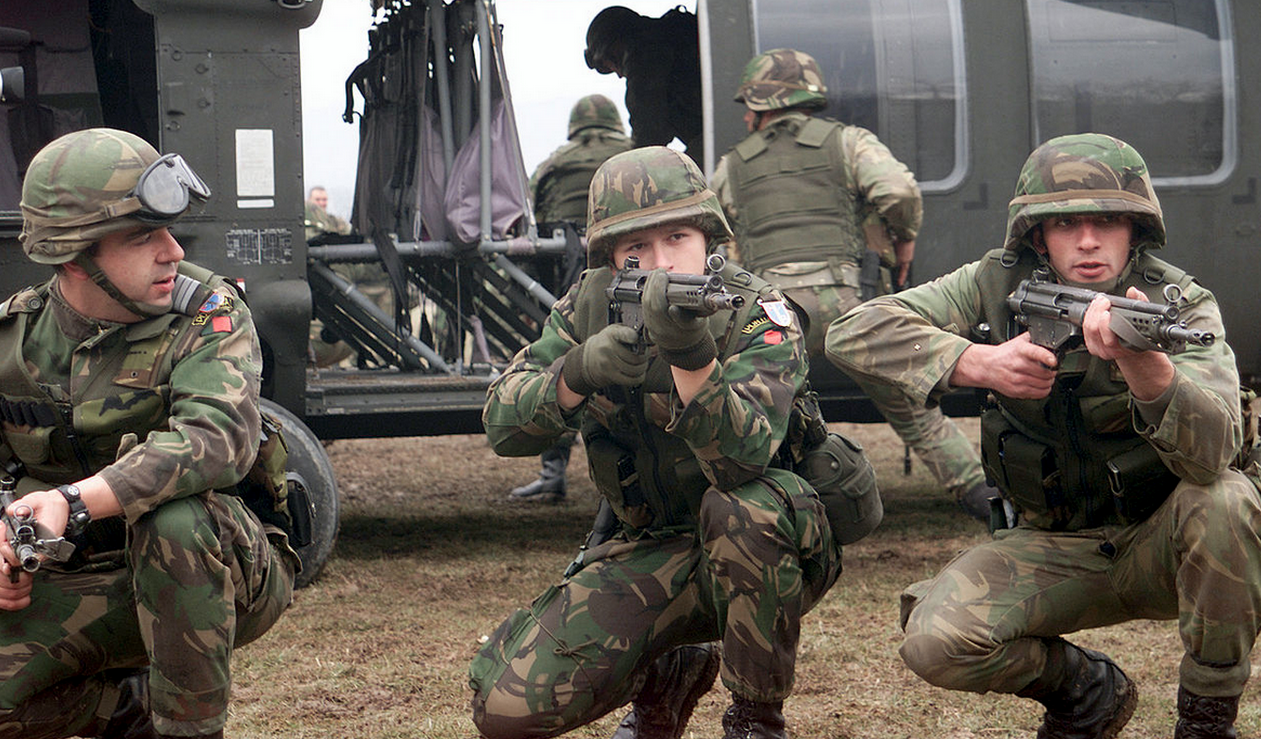

Five years ago, when I entered the Portuguese Military Academy for the first time, this verse by the Roman poet Horatio was the first thing I read, the Academy’s motto written bellow the crest near the metal gate so that everyone who enters through it remembers the true mission of the soldier: to kill and to die for one’s country, as one colleague of mine aptly puts it.

This notion of national service, of fighting and dying for one’s nation-state has been the paradigm since the first national armies appeared alongside the French and American revolutions during the 18th century. Since then, the most important mission of every army is the defense of its nation’s territory and people. I do not doubt this statement; what I have doubted lately is the ability of smaller nation-states like Portugal to defend themselves against today’s globalized threats.

Globalization has made defending one’s country a very difficult business, especially if said country happens to not have the required critical mass of people or resources to develop the required capabilities.

We can also extend this question to other small nations: some with very strong neighbors who threaten their security, like in the Baltics or some with no obvious military threats, like Portugal. Either they are very difficult to defend against likely military threats, or its security can apparently be assured without the need for armed forces. And we are only considering classic military threats. The situation becomes much more complicated once we add in terrorism, cyber, economic or information warfare. These are all global threats, affecting the security of nation-states as much, or much more than ‘classic’ military ones: Even when we begin discussing odds and probabilities, as small as they might be, they are usually larger than the probability of ‘conventional’ armed violence for most Western states. Globalization has made defending one’s country a very difficult business, especially if said country happens to not have the required critical mass of people or resources to develop the required capabilities.

And since I’ve already questioned my choice of career, it only seems logical that now I should question my own nationality. According to thinkers like the Portuguese Marcello Caetano, nation-states exist to assure two things of its citizens: their security and their welfare. While there are many levels of ambition for those two objectives, if a given state fully depends on external agents to achieve both of them, can it really be called a state? Will the globalization of threats change our notion of state?

All this questioning seems to suggest that today, only entities large enough to independently assure the security of its citizens are truly sovereign. Everyone else depends on external agents, or forms networks. And while alliances are as old as the first political entities, back then the world wasn’t so interconnected, and threats weren’t so varied that alliances and networks were a necessity, and not a mere commodity.

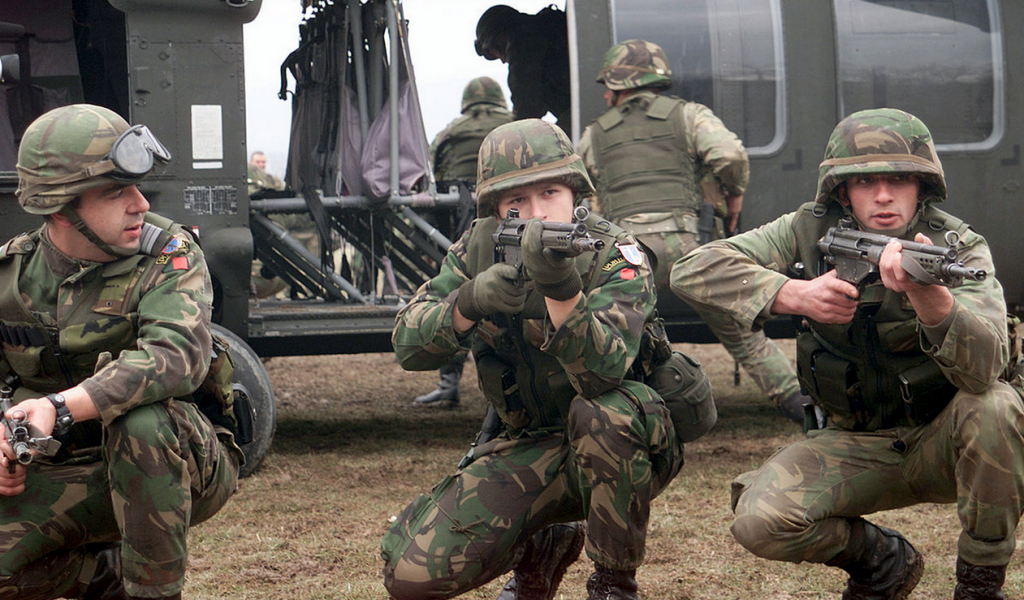

The answer I propose is this: we cannot do defense on our own any more. Globalization has made national security an international concern, so as questionable as the choice of howitzers may be, while my battery cannot hope to defend Portugal on its own it just might help to defend NATO alongside other forces. The same applies even more to information and cyber threats, terrorism, and to everything that affects state security in a non-conventional way. The system is now more important that its parts, but everyone has to understand this to be able to defend it. Especially in Europe, armed forces and other security agents from every state must begin to converge under one structure, and act as one entity: Cooperation must be replaced with coordination.

In the end, I still believe in fighting and dying for the patria in the verse by Horatio; what we, soldiers of the twenty-first century, have to understand is that the patria has changed.