On October 6, 1973 the Israel Defense Forces were surprised when the Egyptian and Syrian armed forces commenced what would become known to Israelis as the Yom Kippur War and to Arabs as the October War. The true surprise, though, was not when and how the war commenced. The Israelis had had some indications that war was coming soon. They had seen the buildup of Egyptian and Syrian forces and capabilities, the increasingly warlike rhetoric of the senior leaders of both Arab countries, and the pattern of activity indicating that war was imminent.

The true surprise came a few hours after the war began, when the Egyptian and Israeli forces made contact. After decisive victories in 1948, 1956, and 1967, the IDF leaders and units were confident that they could rapidly overcome the Egyptians in the air and on the ground and defeat their forces. They maintained that confidence even when initiation of the conflict on a Jewish holy day slowed reactions and mobilization. But reality turned out to be far different from their expectations. In previous wars, in particular the Six-Day War only six years earlier, the Israeli Air Force had dominated the skies and Israeli armored forces had destroyed and humiliated the Egyptian Army on the ground.

But, instead of a quick and decisive victory, the IDF was subjected to a battlefield surprise the like of which they had never encountered. Egyptian investment in mobile surface-to-air missiles, coupled with a dense and layered surface-to-air missile and gun defense denied the air over the Egyptian Army to attack from Israeli aircraft. In fact, Israeli attempts to attack by air were swept from the skies for the first few days of the war. The Israeli doctrine of employing airpower and close air support in lieu of artillery was negated with significant adverse consequences.

At the same time the Egyptians employed an innovative approach to crossing the Suez Canal with ground forces and were able to very rapidly overwhelm the Israeli Bar Lev Line defenses. The Egyptians poured over the canal at a rate totally unexpected by the Israelis and quickly established a layered, antitank guided missile (ATGM), infantry-based defense in depth. Israeli counterattacks were decimated, as the Israelis had expected a tank-on-tank fight they knew they could win and were instead confronted by dug-in, determined Egyptian infantry forces, armed with the latest ATGMs for which the Israeli tank forces had no counter. Tactically in the air and on the ground the IDF was completely surprised and suffered heavy losses during the first few days of the war. That the Israelis were able to overcome this battlefield surprise is a tribute to the adaptability they repeatedly demonstrated in terms of doctrine, organization, command and control, and their ability to rapidly figure out what did work against the new Egyptian capabilities and tactics and to get the word out to the other units within the Israeli Defense forces.

Obviously the IDF experience in the Yom Kippur War is by no means the only battlefield surprise in history; it is not even the only instance that Israeli forces have encountered. The IDF also experienced surprise at the hands of Hezbollah during their attack into Lebanon in 2006. The Israeli Army expected to fight a few disorganized, untrained, poorly led, and poorly equipped terrorists. They were surprised when they were engaged by Hezbollah units that were well-led, disciplined, organized, fighting forces. Those Hezbollah forces were equipped with the most modern small arms and antitank weapons, and fought deliberately from a plan that was designed to defeat the very capabilities the Israeli Army was employing.

An example from beyond the Israelis’ experience is the campaign of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that surprised US and coalition forces during Operation Iraqi Freedom after the initial invasion of Iraq. The United States was expecting to conduct stability operations against a few remaining insurgents and elements still loyal to Saddam Hussein, primarily in small, direct-fire engagements. Instead they were confronted by an organized, systematic, and increasingly more technological campaign employing IEDs to limit US and coalition freedom of action and to create casualties in increasingly large numbers. This was an operational method for which the initial invasion force into Iraq was completely unprepared.

Yet another example of battlefield surprise was the Russian operations in support of separatists in eastern Ukraine in 2014. There, the Russians combined strategic, operational, and tactical cyber operations and information warfare with tactical electronic warfare, unmanned aerial systems, and indirect fires to create cyber- and kinetic-fires strike complexes. Those complexes enabled the Russians to find, fix, and destroy Ukrainian defending forces in a matter of minutes or disintegrate the cohesion and mission command of Ukrainian units and governmental organizations.

These examples confirm what most of us already know: that in almost every conflict some sort of battlefield surprise emerges. In these cases battlefield surprise refers to the surprise generated by new technologies or unexpected doctrine. This is particularly true in twenty-first century warfare, when the pace of technological change is so great and therefore the opportunities to employ combinations of new technologies to create surprise is greater than in the past. Understanding this fact requires us to prepare to encounter battlefield surprise in our future conflicts. Leaders at every echelon have a requirement to prepare their soldiers, subordinate leaders, and organizations to anticipate that surprise will occur, and adapt to and overcome such surprise when it does.

Effectively adapting to and overcoming surprise is not something that can be done spontaneously when it appears. As the four examples noted above illustrate, it is very difficult to adapt to and overcome battlefield surprise in the midst of combat. The fact that it is a surprise means the organization did not prepare for emerging technologies or doctrines ahead of time, had not trained against emerging enemy capabilities, and had not prepared counters to those capabilities. But even absent that preparation, a force can equip itself by developing more flexible and adaptive soldiers, leaders, and organizations, and inculcating in those organizations a culture that is comfortable with battlefield surprise.

Step One: Changing our Mindset

If the US Army is going to be able to adapt to and overcome surprise, we must first admit that we will be surprised and that often we ourselves will be the cause of surprise.

Why are military organizations surprised by new tactics and technologies? There are a number of reasons. First, of course, is uncertainty about the enemy and the operational environment. Second is our expectations and biases, which affect how we see, understand, and visualize future conflict. Third is the fact of co-evolution; as we evolve and improve our capabilities the enemy is co-evolving, trying to field capabilities and tactics that will defeat our own. Fourth is our own hubris, as illustrated by the Israeli and US examples above. These four reasons add up to a simple fact: Battlefield surprise results from a gap between what our mindset suggests is about to occur and what is actually occurring. The significance or adverse impact of that gap is measured by how relevant our mindset is to actual reality. The less relevant our mindset, the greater the adversity caused by the surprise.

To close that gap, we have to address each of those four reasons. The first is related to the intelligence function. In all of the historical cases above the challenge was not one of perception; those surprised knew that mobile air-defense systems, ATGM, IEDs, rockets and unmanned aerial systems existed and moreover could often see them being employed. The intelligence gap grew through unimaginative analysis that only reported the what and where, and not the how and why. One way to address the intelligence gap is through dedicated, school-trained Red Teamers who are constantly looking at how our opponent might combine and innovatively employ their capabilities. Key staff leaders should be sent to the two-week Red Team critical-thinking course, and a dedicated Red Team built within organizations by sending two or three of each organization’s best people to the six-, nine- or eighteen-week Red Team courses. Or, better yet, a mobile training team can be brought to an organization’s location to run as many leaders and staff personnel as possible through an introductory version of the course. Then, most importantly, when analyzing, planning, or deciding, we must listen to these Red Teams to anticipate battlefield surprise.

The second challenge is overcoming our expectations and biases. Certainly developing a Red Team–enabled, critical-thinking mindset will help correct this flaw, which all humans and organizations exhibit. But, that is not enough. What we can do procedurally is to deliberately and actively recognize and account for our individual and organizational biases during MDMP—the military decision-making process. One approach would be to formally add “Account for Bias” into step two of MDMP along with the development of “assumptions.” Too often the assumptions we develop in this MDMP step are unconsciously driven by our own biases. Formally admitting and accounting for them can help to mitigate this problem and its contribution to battlefield surprise. A good start is for commanders and staffs, not just intelligence personnel, to read and discuss Richards Heuer’s Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, with its thorough and practical approach to overcoming bias in analysis and decision making.

Failing to recognize and account for co-evolution is the third challenge to overcoming battlefield surprise. In almost every case, technological or doctrinal surprise is a result of an enemy adapting in response to problems presented to them by the surprised force previous evolution. For example, in the early Arab-Israeli wars of 1948 and 1956, the IDF had limited air force capabilities. By the 1967 Six-Day War the Israeli Air Force had evolved into one of the decisive factors in the war, significantly defeating both Egyptian air forces and air defense. As a consequence the Egyptians “co-evolved,” maturing their air defenses into a complex, layered system integrating fixed and mobile platforms and gun and missile capability. The IDF’s failure to see and adapt to this evolution led to their battlefield surprise in the air domain.

The fourth major challenge is our own hubris. The US Army after its lightning victory during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the IDF after the overwhelming victory in the Six-Day War, and the IDF again in approaching the 2006 war in Lebanon: these all are examples of hubris setting the conditions for a future battlefield surprise. The IED campaign in Iraq, the ATGM and air defense surprise of the Yom Kippur War, and Hezbollah’s hybrid success against the IDF all resulted in large measure from excessive self-confidence on the part of the US and Israeli militaries. Military commanders, staffs and organizations who are less convinced of their invincibility are far less likely to suffer a major battlefield surprise. This requires sustained effort by leaders at all levels to communicate a clear message to their subordinates: “Yes, you are a very good soldier in a very good Army, but our future enemies are working just as hard as you are and are dedicated to defeating us next time around, in part by turning your confidence in your abilities into a weakness and in part by exploiting their own advantages. We are not perfect, we can be surprised, and we can be beat.”

Step Two: Leader Development

Leader development for adapting to and overcoming battlefield surprise should be based on a solid knowledge of the associated theory and doctrine. A good start is a reading and discussion program. Leaders, officers and noncommissioned officers alike, should read to prepare to overcome surprise and then discuss to reinforce what they read and consider its application to their own units and circumstances. One approach is to read a book a month and then have a “brown-bag lunch” leaders’ discussion of the implications of the book. A starter set of books includes: Mier Finkel’s On Flexibility, Zvi Lanir’s Fundamental Surprises, Barton Whaley’s Strategem: Deception and Surprise In War, and current doctrine. Each of these works lends itself to breaking the reading into bite-size chunks that can be assigned to different leaders to lead group discussions.

Wargames

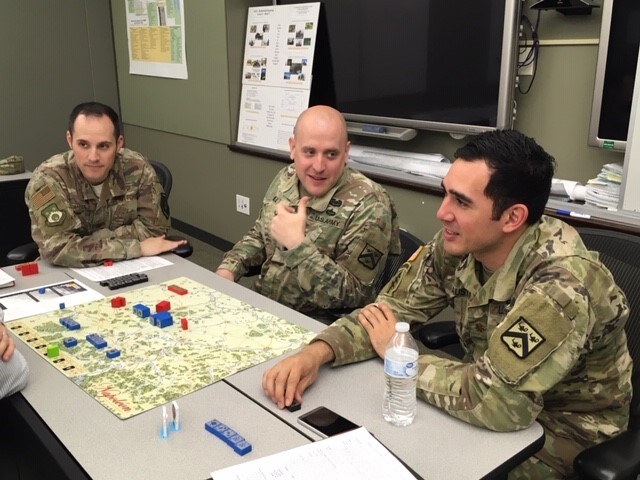

One way to introduce and reinforce the concept of battlefield surprise and adapting to that surprise is through the use of wargames for leader development. A wargame can be set up, played to confront the leaders with battlefield surprise, and then discussed in an after-action review in a relatively short period of time. Prep in the form of reading the rules and watching one of the many online videos that illustrate the game play should take no more than a half hour. Actual play can be accomplished in two hours if a moderately difficult game is selected. That play would include injection of a battlefield surprise halfway through the game. During an elective course on battlefield surprise at the Command and General Staff College, in two hours field-grade leaders set up and played the boardgame Napoleon: The Waterloo Campaign 1815, and then conducted an after-action review of their response to surprise in the game.

Halfway through the game the French were allowed to employ hot-air balloons (invented by the French Montgolfier brothers in 1783) to vertically envelop infantry battalions and for indirect fire observation, giving them a range advantage. In the after-action review, the players opposing the French analyzed their emotional and cognitive response to the technological and doctrinal surprise and the French players analyzed the integration of the surprise into their operations in terms of maximizing effectiveness. The training event proved simple, yet effective in generating discussion and thought about training and developing leaders and units to overcome battlefield surprise.

Sand Tables and Table-Top Exercises

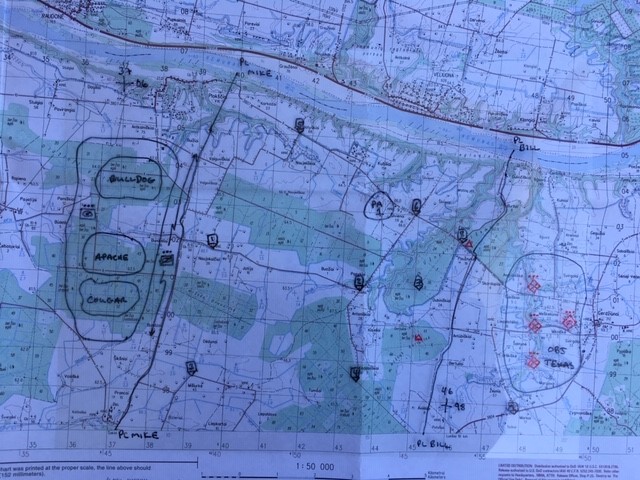

Simple sand-table or table-top exercises are equally effective at introducing leaders and staffs to the concepts of battlefield surprise and adapting to and overcoming such surprise. A sand-table exercise can re-create a historical example or a current scenario to demonstrate the concepts inherent in technological or doctrinal surprise and then either illustrate the actual adaptations by the surprised force or provide an opportunity for the participants to think through how they would adapt to and seek to overcome such a surprise. These exercises are inexpensive, quick, and powerful tools for educating leaders and staffs about confronting and responding to battlefield surprise.

The example in the photo above shows a table-top exercise that re-creates the IDF’s ATGM and mobile air-defense surprise by the Egyptians in the Yom Kippur War. The simplicity of the table-top format focuses the learning and discussion on surprise and not the myriad of other considerations.

Mini-STAFFEX

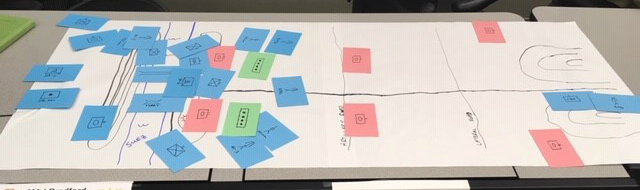

It is important to remember that battlefield surprise occurs in real time. Whether it is ATGMs, IEDs, or hybrid tactics, the surprised force must begin to adapt immediately—or suffer increasing casualties, loss of systems, and defeat. Therefore, training and leader development should require both surprise and adaptations in real time. For example, one way to train a staff to overcome battlefield surprise is to present them with a map, a situation (e.g., a US battalion attacking a defending enemy company), and a surprise (e.g., the defending enemy possessing a swarm of unmanned ground vehicles), and then have the staff produce a solution.

A better way is to conduct a mini-STAFFEX (staff exercise). This can be accomplished in the staff’s conference room with just a map, an overlay, and a script. After assembling the staff and orienting them to the situation and the map, start the STAFFEX as if the staff were in a tactical operations center. The script can situate the unit in its assembly area as it is preparing for an attack. Then, suddenly the staff starts receiving calls in real time from subordinate elements that they are being swarmed by unmanned ground vehicles. The calls can simply be from the unit commander or a tasked subordinate in the room reading from the script. There is no need to add mock realism by using real radios; simplicity focuses the learning on the surprise event. As the situation unfolds, repeated calls over time from different subordinates develop the surprise for the staff. Meanwhile, the clock ticks down toward the appointed time to conduct an attack that still must take place, which keeps the pressure on the staff and forces them to adapt in real time. An example of such a STAFFEX that can be conducted start to finish in less than an hour, including an after-action review and using only a map, overlay, table, and chairs is provided below. Needless to say, during the preparation for the STAFFEX the script and the surprise must be kept from the participants so they are truly “surprised” during the actual event.

Planning to Anticipate

Another training event that can help units to be able to adapt to and overcome battlefield surprise is in the planning process. As the cases discussed at the beginning of this article suggest, much of the technologies that create surprise are already known to the surprised organization. The IDF knew before the Yom Kippur war that the Egyptians had mobile surface-to-air missiles and ATGMs. The United States military knew about IEDs, had observed them being employed throughout the Middle East, and had significant experience with them in the form of booby traps in Vietnam. Thus, planning must include anticipation of battlefield surprise or innovative combinations of existing or emerging technologies.

The Army Design Methodology (ADM) can serve as the catalyst for anticipating battlefield surprise and developing adaptation strategies. In the initial effort of applying ADM the organization assesses the operational environment. The people involved in ADM then derive the problems that will have to be overcome in that environment in order to accomplish their mission. The appreciation of the operational environment and attendant emergent problems enables the staff to envision opportunities for enemies to generate battlefield surprise. This is not to suggest that every possible surprise can be identified ahead of time through ADM, nor that ADM will produce solutions to future surprises. But, there is the opportunity to identify some potential surprises and prepare for those. Additionally, the mere act of considering emergent technologies and battlefield surprise while executing ADM, and later the military decision-making process, develops in the staff an inclination to be aware of and anticipate that they will be surprised and will have to adapt.

Step Three: Individual Training

Training leaders is important, but it is not sufficient. As the battlefield becomes more distributed, urban terrain more cluttered, and operations less contiguous, individual soldiers must also recognize, adapt to, and overcome battlefield surprise. Thus, individual training must incorporate battlefield surprise and enable soldiers to develop the physical, mental, and moral skills and attributes necessary to adapt when they are confronted by something new on the battlefield.

Adaptive Soldier Leader Training and Education

An approach to accomplishing this training and development objective is to employ Adaptive Soldier Leader Training and Education. This is outcome-based training, in which the soldier or leader learns both by doing and by achieving the desired outcome. The focus is on critical and creative thinking, innovation, determination, and adaptation in order to accomplish a particular task in a situation that is structured to deliberately be ambiguous, time-compressed, and complex. The use of outcome-based training promotes the knowledge, skills, attributes, and characteristics that adaptive soldiers, leaders, and units must have in order to adapt to and overcome battlefield surprise.

For example, a soldier or group of soldiers might be given a situation in which they are conducting a reconnaissance patrol and are engaged by kamikaze drones. They must then figure out how to accomplish their mission in the face of this new, unforeseen threat. After the mission is complete, the focus of the after-action review is not on a set of processes or procedures but rather on how the soldiers and leaders adapted to and overcame the challenges while accomplishing the mission. Characteristics such as flexibility and innovation are rewarded, while application of rote memorized tactics or procedures that fail, or continued adherence to a plan that is clearly not working, are pointed out as negative learning.

Sergeant’s Time Training: “What If . . .”

Developing in individual soldiers a mindset that they will have to recognize and adapt to battlefield surprise cannot be done with a single training event. It will require repeated repetitions exposing them to surprise over time to change their thinking and reactions. A technique is to use the last five minutes of each “sergeant’s time” session to reinforce the importance of adapting to battlefield surprise. This can be accomplished by a single exercise in which the sergeant asks his or her soldiers a “what if” question that encourages them to imagine being confronted by some technological or doctrinal surprise. For example, after a squad trains on executing the four-man stack, the squad leader might ask, “What if the enemy suddenly starts using flame weapons in an urban area?” Or, “We have the Black Hornet micro-UAS. What if all of a sudden you saw a swarm of those moving through the building to your front?” The question is followed by a short discussion in which the goal is to emphasize the individual soldier’s role in recognizing the surprise as new capabilities or tactics emerge, personally adapting to the new situation, overcoming the immediate effects, and then reporting up the chain of command so the organization can begin to adapt to battlefield surprise.

Step Four: Collective Training

Ultimately adapting to and overcoming battlefield surprise is an organizational effort that spans multiple echelons. Thinking back to the IDF experience confronting ATGMs in 1973, individual tanks had to immediately adapt their tactics to survive the ATGMs. But, companies, battalions, and brigades had to reorganize to create combined-arms organizations from pure units, so they could defeat the infantry-heavy Egyptian forces. Staffs had to develop new tactics to overcome the lack of artillery, since their air force was initially driven from the skies by the mobile surface-to-air missiles. Thus, organizational collective training must place units in surprise situations, so they learn in training to adapt.

Battlefield Surprise in Situational Training Exercises

The key training effort should focus on injecting battlefield surprise into situational training exercises (STX). Today our typical STX lane is focused on execution of selected collective tasks in simulated battlefield conditions against a live opposing force (OPFOR). Yet, with a slight modification that STX lane could include a battlefield surprise that forces the training unit to adapt in order to accomplish its mission. For example, we could modify a company offensive STX to include a battlefield surprise. The STX lane could be run initially without the battlefield surprise, focusing on the tasks that need to be trained. After an after-action review, the company would conduct a second run, during which everything will be the same as the first iteration until the company crosses a designated phase line. At that point a simulator goes off and the company is informed that an electromagnetic-pulse weapon just went off and all vehicles must immediately halt, all radios are turned off, and no electronics can be used. The company must then figure out how to accomplish the mission in the new situation. Once the mission is accomplished, the after-action review can focus on how the unit adapted not just to accomplish the mission (perhaps dismounted), but also to report to higher (perhaps using runners), employ indirect fire (perhaps using pyrotechnic signals), etc. The same STX can be conducted using simulations with the Virtual Battlespace 3 training system without going to the field. The key is being exposed to an unanticipated surprise and focusing on innovative solutions to new problems.

Command Post Exercises

Using the mini-STAFFEX discussed above as a “walk” phase of training, the “run” phase can be the injection of technological or doctrinal surprise into the master scenario events list for a command post exercise (CPX). For example, the staff might receive reports that certain enemy units are employing an active protection system that is defeating friendly direct-fire systems. Or, if the CPX is being driven by a simulation, the same effect could be replicated by increasing the defensive strength of the enemy units. This forces the staff to adapt in real time to the surprise. Another option might be a cyberattack that affects certain command-and-control systems.

Battlefield Surprise at Combat Training Centers

Our Combat Training Centers (CTCs) are the pinnacle of collective training. For that reason units who have trained to confront battlefield surprise and commanders who desire that their units be more adaptive if surprised in battle should integrate battlefield surprise into CTC rotations. In coordination with the CTC, senior trainers can request that their units be exposed to battlefield surprise during force-on-force or live-fire events. Technological surprise might take the form of extended ranges, lethality, or protection of laser engagement systems, or might include new forms of obstacles or deception. A doctrinal surprise might be similar to the IDF experiences in 1973 and 2006: in both cases the tactics the IDF expected to confront were the exact opposite of what they did experience. For example, a unit might go to the National Training Center expecting to fight a primarily mechanized OPFOR and instead fight a primarily air-mobile OPFOR or a smaller than normal light infantry OPFOR with significantly greater indirect-fire support. The combination doesn’t matter as much as the surprise being sufficiently great that all elements of the unit, from the staff down through subordinate units to the team/crew/section level, are forced to adapt and overcome an unexpected technology or tactic.

Some Quick Training Calendar Math

Adding more to the training calendar is always hard and there are always competing priorities and tradeoffs. Time is the enemy, because there are so few training days and training hours in a year. So, to help leaders in making the decision of whether to incorporate training and leader development in battlefield surprise, here is the time associated with the training described above:

Time Required for Leader/Individual Training

Reading Brown-Bag Lunches (1 per month) — 10 hours

Adaptive Soldier Leader Training and Education (1 per quarter) — 8 hours

Time Required for Staff Training

Wargame (1st Qtr) — 3 hours

Sand Table (2nd Qtr) — 2 hours

Table Top (3rd Qtr) — 2 hours

Mini-STAFFEX (4th Qtr) — 2 hours

For the remainder of the suggested training events (planning, sergeant’s time, CPX, and CTC rotations), the battlefield surprise aspects are integrated into the training event, so no extra time is required. What this means is that for about four hours per quarter commanders can prepare their organizations to adapt to and overcome battlefield surprise.

Conclusion

There is a reason surprise is one of the doctrinally recognized nine principles of war. That reason is that gaining surprise over an adversary can significantly shift the odds, as it did in the Yom Kippur War and Operation Iraqi Freedom, or translate into successful battles, as it did in Lebanon in 2006 and eastern Ukraine in 2014. It took the United States several years and several billions of dollars to marginally adapt to and overcome the IED campaign in Iraq, while losing thousands of lives and suffering tens of thousands of wounded.

It is the responsibility of leaders at every echelon to prepare their organizations to adapt to and overcome technical and doctrinal surprise in the next conflict. That starts with each organization realizing and admitting that being surprised results directly from our failure to anticipate, our bias, our failure to see how the enemy evolves, and our hubris. It continues with changing our organizational mindset from one that expects predictability and enemy conformity to our vision of the fight to one that expects to be surprised. And, it continues further with a deliberate and sustained program of training and leader development to develop the individual and organizational adaptability to overcome battlefield surprise in future conflicts. As the Army and the joint force prepare for large-scale, multi-domain combat operations, our future success and survival may very well depend on our preparation to adapt to and overcome battlefield surprise.

Continue reading below for mini-STAFFEX example.

Dr James Greer is currently an Assistant Professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Featured image credit: Maj. Joseph Payton, US Army

A321 MINI-STAFFEX

Positions

XO

S2

S3

FSO

ENGR

AMD

ALO

IW/CYBER

Call Signs

LION – Brigade

TIGER – Task Force

APACHE – Tank CO

BULLDOG – Mech CO

COUGAR – Mech CO

SABER – Scout PLT

SMOKE – Mortar PLT

BREACHER – Engineer CO

SCORPION – Air/Missile Defense PLT

TRUCKER – Support

HACKER – HHC

FRAGO 1

SITUATION: TIME 0845… TF TIGER is in hasty atk pos titans

obj texas is defended by an ethnic Russian separatist dismounted infantry company with a platoon of T-72 tanks. After an initial offensive, over the last several days the separatists have been pushed back and are trying to defend the ground they had seized. the dismounted company is estimated as at 80% personnel, but low on ammunition and with probably only a few rpg-18 as anti-tank weapons. the three t-72 tanks are estimated to be fully operational, but with poorly trained crews. separatists have some mortars in support. russian 152mm artillery and 240mm rockets are in range, but russia has not yet engaged nato forces and appears to be reluctant to do so out of fear of escalation of the conflict.

mission: tf tiger attacks 0930 to secure obj texas to pass follow-on forces east.

concept of operations: tf tiger attacks with tm bulldog (2 x mech/1 x tk) as main effort along axis of checkpoints 5, 6, 8 into northern flank of obj texas. cougar attacks as supporting effort along axis of checkpoints 3, 4, 9 into southern flank of obj texas. tm apache (2 x tk/1 x mech) in reserve follows tm bulldog and prepares to assume main effort or support by fire from checkpoint 8 or checkpoint 7. saber initially screens along ld (PL mike); o/o establishes TCP at checkpoints to pass follow-on units. smoke supports initial attack from ATK POS titans; o/o jumps to PA 1 and supports assault of obj texas with priority of fires initially to saber; after ld in order bulldog, cougar, apache.

service support: TF tiger is at 100% for major systems; 95% personnel; and is green on all classes of supply. the tf personnel are tired after almost two months of continuous deployment and operations, but moral is high as they are on the offensive and are clearly better trained and led than the separatists.

command and signal: tiger 6 co-located and moves with tm apache. toc co-located with mortar platoon. remains in place when mortars jump forward to pa 1. toc displaces forward to obj texas after objective is secured.

tiger 5 this is apache 6 over.

tiger 5 this is apache 6. tiger 6’s tank is completely destroyed. explosion 5 minutes ago. sent a31 over to investigate. all 4 crew kia. tank looks like it hit an efp ied in the left rear. except it couldn’t be an ied. tiger 6’s tank hasn’t moved for over an hour.

tiger 5 this is saber 6 over.

tiger 5, saber 6. about ten minutes before tiger 6’s tank blew up we saw four things go by us slowly. At the time we thought they were just boars. they were about that size, but maybe they were something else. maybe ugv.

TIGER 5 THIS is apache 6. think saber 6 is correct. there is some sort of small destroyed vehicle in the debris next to tiger 6’s tank. there are a number of tracks that look like small tank treads. tracks continue past our position toward bulldog.

tiger 5 this is lion 6. i’ve lost contact with tiger 6. can you give me a quick sitrep and get him up on the net so i can talk to him? want to check signals with him before you ld in…x minutes.

tiger 5, scorpion 6. engaging small uas over bulldog’s position. single uas hovering – looks like a scout

tiger 5, saber 6. engaged approx. ten small vehicles, appear to be UGV moving southwest vic FG383007. ugv moving very fast, 15-20 kph.

tiger 5, saber 6. destroyed two ugv. one armed with AN EFP and one armed with 30mm cannon. looks like telescopic sight with antenna for communications.

tiger 6, bulldog 6. being engaged by multiple cannon from vic the fg4004 grid square. more than 7 weapons firing, possibly ugv saber is reporting. weapons engage and then move laterally and reengage. am returning fire and repositioning to hull down positions.

tiger 6, bulldog 6. b13 rammed by ugv armed with efp. b13 mobility kill, driver wounded, not critical.