John Spencer and Jayson Geroux | 02.26.22

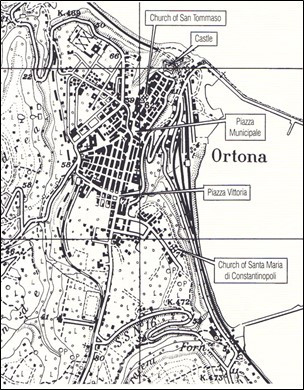

The battle of Ortona occurred between German and Canadian forces from December 20 to December 27, 1943, during World War II (1939–1945). A coastal town in central Italy, Ortona sits on a plateau overlooking the Adriatic Sea. The newer, southern part of Ortona had larger structures that were separated from each other while the buildings in the older, northern portion were more tightly packed, often with no space between them. There is one main thoroughfare through the center of the town, Highway 16. The many secondary streets are extremely narrow, some only wide enough for oxcarts and pedestrians. Ortona had a prewar population of ten thousand residents.

Ortona was the first prolonged urban battle of the Italian campaign, which began in Sicily in the summer of 1943 and continued with the invasion of the mainland in the fall. The battle came at a critical moment for the German military, which remained as an occupying force in Italy after the Fascist government fell and effectively controlled the parts of Italy not yet liberated by Allied forces on their northward campaign up the peninsula. Strategically, Rome was important. If it fell to the Allies there would have been extreme political, military, economic, social, and psychological ramifications for both sides. To prevent this, the German forces at the operational level took advantage of Italy’s mountainous geography and combined it with manmade obstacles to favor their defense along a series of defensive lines centered on a series of deep valleys and wide rivers. In October 1943, Adolf Hitler instructed his Mediterranean theater commander, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, to establish the Gustav Line, a cross-country defensive position across the narrowest part of Italy.

The Germans had established Ortona as the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line because if Allied forces were to advance north from Ortona they would reach Pescara, from where they could take advantage of roads and mountain passes that gave access to Rome from the northeast. Unfortunately, the Canadians, on the Allies’ northeastern flank, did not know that Ortona was the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line. British 8th Army intelligence believed that this line was just north of the town along the Arielli River valley; until that point German forces had typically established defensive lines along deep valleys throughout the campaign, with urban areas only ever being held for very brief periods of time to allow for these defensive lines to be constructed.

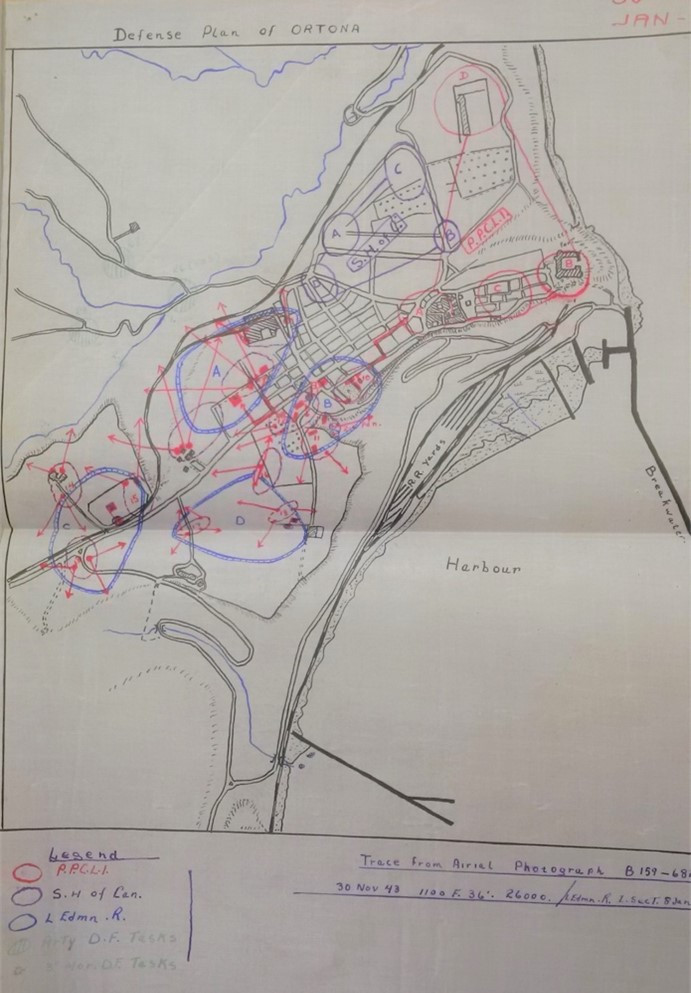

The battle involved the 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade (2 CIB), with an infantry battalion from the Loyal Edmonton Regiment (the “Loyal Eddies”), an infantry battalion from the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada (the “Seaforths”), and an infantry battalion from the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (the “Patricias”). In support were the 12th Canadian Armoured (“Three Rivers”) Regiment, the Royal Canadian Engineers’ (RCE) 4th Field Company, and the Royal Canadian Artillery’s 90th Anti-Tank Battery’s six- and seventeen-pounder guns. The German defenders were the 2nd Battalions of the German 3rd and 4th Regiments of the 1st Parachute Division.

Ortona was a defender’s dream. It sat on a steep-sided plateau perched above the Adriatic Sea, which largely removed German concerns about an attack on either flank, allowing the defenders to concentrate their forces on the southern approach. German Wehrmacht units initially deployed in and around Ortona in September 1943. In December, the town and the area west of it became the responsibility of the 1st Parachute Division. The 2nd Battalion, 3rd Parachute Regiment’s mission was to halt 2 CIB’s advance up the coastal Highway 16, which cut through the center of Ortona, by making a carefully planned defensive stand in the town. The Germans also took full advantages of the inherent complexities of the urban geography itself. They destroyed many buildings so the rubble fell into the secondary streets, creating piles ten to fifteen feet high, which were then sown with booby traps and mines to block any advance up any street that was not through the center of town. The defensive scheme of maneuver inside Ortona was to hold a line of forward positions in the town’s southern outskirts, after which the defenders would withdraw into the heart of the town, enticing the Canadians up Highway 16—invitingly left clear of rubble, unlike the secondary streets—and into their main defensive area, the various piazze (squares), where the Canadians were to be destroyed. The buildings around the squares had several machine gun positions protected by marksmen and antitank guns on several floors of every structure. Doors, windows, and furniture—even toilets—were booby-trapped with explosive devices. The Germans had also destroyed the walls on one side of each of several buildings so that the Canadians, thinking they were walking into a room that would give them shelter as they approached the far side of a building, could be observed and then gunned down by the Germans positioned across the street. German artillery was planned to blanket Canadian positions as they advanced through the town. The obstacle and defense plan gave the Germans the advantages of an interconnected network of well-protected, three-dimensional mini-fortresses with sub- and supersurface capabilities. All of these defenses were meant to stop the Canadian advance toward the northern end of the town, thus assisting the overall German strategic and operational intent of stopping the Canadians from advancing from Ortona north to Pescara.

The Battle

On December 20, 2 CIB established itself a few hundred meters south of Ortona. However, because they did not realize that the town was the Gustav Line’s eastern anchor, only the Loyal Eddies were initially committed to the urban fight, although they had the Three Rivers Regiment’s C Squadron of tanks and the Royal Canadian Engineers’ 4th Field Company in support. The Seaforths’ only task at this point was to approach the town’s southeastern limits to act as flank protection, while the Patricias remained the brigade’s reserve.

On the morning of December 21, the Loyal Eddies confronted initial challenges gaining lodgment but fought their way into the town’s southern outskirts, where they observed the large, booby-trapped rubble piles. To remove the obstacles the Three Rivers’ tanks and the 90th Antitank Battery’s six-pounder guns were moved up to fire at the piles. This reduced the piles enough to allow the accompanying infantry and engineers to overcome them and work their way further into the town’s southern outskirts. On the afternoon of December 21, these combined arms units fought up Highway 16 and used it as the axis of advance to fight to the southern limits of Piazza della Vittoria. It was not possible to advance up the secondary streets because the tanks and antitank guns could not be used to support the infantry and engineers. The Loyal Eddies and their engineers also had to enter buildings through doors and windows on the main floors and fight from the bottom up, which give the German defenders inside the buildings the initiative. With the doors and windows booby-trapped, the Germans positioned inside were able to fire at the Canadians when they came in through the obvious entry points. Concurrently, the Seaforths’ infantry battalion continued to protect the eastern flank by fighting toward the southeastern portion of the town and clearing the church of Santa Maria di Constantinopoli after a sharp and bitter battle. Every night until the end of the battle, the Germans would attempt to infiltrate into the Canadians lines, resulting in bitter close-quarters and hand-to-hand combat. From the evening of December 21 onward, both sides attempted to demoralize and destroy one another by raining artillery down on the town.

On December 22, C Squadron’s tanks and the 90th Antitank Battery’s six-pounder guns blasted away at German positions around Piazza della Vittoria, allowing the Loyal Eddies and their accompanying engineers to slowly fight their way around to clear the square. D Company’s Major James Stone then moved out of the square and conducted a penetration up Highway 16 with the tanks and engineers supporting. Stone took the risk of not clearing the buildings en route. This surprising move was initially successful, but the element was subsequently stopped by a large rubble pile and surface-laid mines at the northern end of the road at Piazza Municipale. B Company kept pace just to the east on Corso Garibaldi. The Seaforths, still not fully committed to the battle, destroyed a German mortar crew that battered the Santa Maria di Constantinopoli church and then advanced to the now-cleared Piazza della Vittoria with the task of protecting the Loyal Eddies’ left flank.

On December 23, 2 CIB’s commander, Brigadier Bert Hoffmeister, decided to commit more resources to the battle after realizing that Ortona was the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line and that they were in for a lengthy urban battle. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s commander, Major General Christopher Vokes, also directed 1 CIB and then 3 CIB to move up the steep north-south ridge west of Ortona to cut off and isolate it at its northern end. Brigadier Hoffmeister directed the Seaforths to enter the fight by moving to the western side of the town and then turning northeast to link up with the Loyal Eddies at Ortona’s northern end, however just moving to the town’s western side had the Seaforths facing determined resistance. Hoffmeister also directed eight more tanks to be given to each infantry battalion. Three seventeen-pounder antitank guns with three tanks also established a position on high ground 1,500 yards southeast of Ortona to batter German defenses in the northeast corner of the town. Since the Canadians had never fought such a protracted urban battle before, they did not have the proper equipment. They adapted quickly and improvised with the tools they had on hand. They also maintained a combined arms approach throughout the battle.

Canadian forces also evolved their tactics during the battle. When the Canadians had fought their way to the older part of the town, they encountered buildings that were much more densely situated than those in the south, with many of them sharing adjoining walls. Recognizing this, and after clearing a building of the enemy, Captain Bill Longhurst of the Loyal Eddies’ A Company directed his infantry pioneers and engineers to use explosives to blow holes on the top floors of the connected buildings to move from one to another via the upper levels. This helped to address the problem of heavy casualties they were taking when soldiers were exposed on the streets and entering through booby-trapped doors and windows to clear structures from the bottom up. After the holes in the top floors were created, the Canadians utilized grenades and small arms to enter and clear the rooms. From that point forward, they began clearing buildings from the top down, killing the surprised Germans with explosive charges or showering them with grenades and automatic fire while moving downward. After clearing the building, the Loyal Eddies would just return to the top floor of the now clear building to repeat the process into the next one. Soon, the Seaforths were copying this technique, called “mouseholing.”

The Canadians demonstrated great adaptability as they now entered into the heart of the German defense. The Three Rivers Regiment tank personnel began using different types of ammunition—the first round to strike a building was an antitank shell to make the hole and initially kill whoever was inside, and the second was a frangible round that would be fired through the newly created hole to finish off the remaining Germans inside. The tanks rapidly became a vital part of the infantry and engineer assaults of enemy-held buildings. The tanks were also used as sustainment platforms during lulls in attacks, bringing ammunition and supplies up to the front lines and ferrying the wounded back to casualty collection points.

December 24 saw little forward movement for the Canadians for several reasons. In response to the increase in resources the Canadians dedicated to the battle, the Germans did the same, reinforcing the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Parachute Regiment with the 2nd Battalion, 4th Parachute Regiment. Adolf Hitler had also declared that the town was to be held at all costs. The Canadians had now reached several squares that represented the town’s main defensive area. This was where the Germans wanted to make their determined stand. The Loyal Eddies, engineers, tanks, and antitank guns had to reduce the rubble pile at the southern entrance of Piazza Municipale first. They then started a slow fight clearing the buildings around the square. On the western side of the town the Seaforths, after overcoming heavy resistance and German artillery fire, finally arrived at Piazza San Francesco—nicknamed “Dead Horse Square” by the Seaforths due to a corpse of that animal in the middle of it. After a failed counterattack that had to be beaten back by the Seaforths and their supporting engineers and tanks, the Germans put up a weak demonstration of resistance at a school and lured a squad of eight to ten Seaforths into it. The defenders then withdrew from the building and blew preplanted demolitions inside the structure to make it implode. Only one Seaforth, found three days later, survived the blast.

The stalled advance continued the next day, December 25. Although the level of violence between the two sides did not abate, short tactical pauses of thirty minutes to two hours occurred as Canadian companies or smaller groups of soldiers broke away from the front lines to have Christmas dinners before returning to the increasingly violent fighting. For the remainder of the day, the Canadians were content to let their tanks, antitank guns, and artillery wreak havoc on German positions in and around the central squares.

Fierce combat continued into December 26. After finally clearing Piazza Municipale, the Loyal Eddies and their supporting units had to conduct a three-way advance due to the multiple roads that exited north from this square. Although combined arms cooperation had been quite good throughout the battle, it suffered a setback when the Three Rivers lost two tanks in Piazza Plebiscito that were struck by two German antitank guns housed on the second floors of two separate buildings. These were the only tank losses throughout the entirety of the battle. The loss of the tanks forced the Canadians to supply more tanks, antitank guns, engineer-created explosive devices, and artillery to clear Piazza Plebiscito by the end of the day. Concurrently, the Seaforths continued to apply an incredible amount of violence in Dead Horse Square, using eight tanks and attached antitank guns to blast away at German positions in the buildings around the square, which included a hospital and a church. After employing this firepower and seeing hand-to-hand combat over the course of three days, the Seaforths finally got past the square and begin the advance northeast up the Via Monte Maiella to reach the Loyal Eddies in Piazza Plebiscito by the end of the day.

December 27 was the last day of fighting inside the town. With the soldiers of 2 CIB inching their way to the northern end of Ortona, those of 1 CIB and 3 CIB fought their way northwards to the west of the town. As these forces closed in and Ortona’s northern portion faced isolation, the Germans decided to withdraw completely. However, they created an extremely violent deception plan to make it appear that they were staying for good. They destroyed additional buildings to create more rubble and, repeating what they had done to the Seaforths, they demolished a building at Piazza San Tomasso that was temporarily sheltering a Loyal Eddie platoon; only one soldier survived the demolition, also found three days later. This particular event was communicated throughout 2 CIB quickly and—combined with heavy casualties suffered and intense combat endured—led the Canadians to let overwhelming firepower and violence decide the battle once and for all. Canadian tanks, antitank guns, small arms, explosives, mortars, and artillery broke the silence every few seconds throughout the day, pounding the northern end of the town. The Loyal Eddies blew up two buildings full of Germans. The Seaforths, temporarily stalled at a large mill on Via Monte Maiella due to stubborn enemy resistance, destroyed the building with a number of demolition charges planted in its basement. The Loyal Eddies cleared Piazza Plebiscito and advanced far enough into Piazza San Tomasso’s west side and up Corso Umberto and Piazza San Tomasso’s east side to effectively control that square. By the end of the day the Seaforths had linked up with the Loyal Eddies at the northern end of the town. The next day, December 28, both Loyal Eddies and Seaforth soldiers discovered that the Germans had withdrawn from Ortona. 2 CIB’s third battalion, the Patricias, with its supporting Three Rivers tanks, conducted a forward passage of lines and advanced out of Ortona’s northern end. The remainder of 2 CIB immediately transitioned into preparing to defend Ortona from any counterattack as well as beginning a weeks-long process of cleaning up the town to turn it into a rest and recreation center for the British 8th Army.

Although the liberation of Ortona was a success, the month of the battle became known as “Bloody December” by Canadian forces because of the high casualty levels in and around the town. Over the course of the battle almost 4,800 members of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division had to be evacuated as casualties or because of battle exhaustion and illness. Those who fought the battle remembered it as “Little Stalingrad” due to the brutality of its close-quarters combat and the high amount of violence, only worsened by the rubble of the town and the extensive use of tanks, antitank guns, explosives, mortars, and artillery.

The sheer amount of ammunition used by Canadian forces illustrates the intensity of this battle. Soon after the battle began individual infantry soldiers from both the Loyal Eddies and Seaforths were each given a daily issue of twelve to fifteen grenades, and Canadian engineers eagerly used an abundance of abandoned German munitions and mines on top of their supply of explosives to create mouseholes or bring down houses. In just eight days of fighting, the Loyal Eddies used 918 antitank shells, 4,050 three-inch mortar rounds, two thousand two-inch mortar rounds, fifty-seven thousand .303-caliber rounds, 4,800 submachine gun bullets, six hundred No. 36 “Mills bomb” hand grenades, and seven hundred No. 77 smoke grenades.

For the fighting from December 20 to December 27, the Canadians suffered 108 killed in action and 191 wounded in action. Sixty-three Loyal Eddies were killed and 109 wounded; the Seaforths suffered forty-one killed and sixty-two wounded; and in the Three Rivers Regiment, four were killed and twenty wounded. While 1st Parachute Division records were never recovered, casualty reports of the LXXVI Panzer Corps, which the division was part of, stated that during a nine-day period spanning the battle of Ortona the division suffered sixty-eight soldiers killed, 159 wounded, 205 missing, and twenty-three that fell sick, amounting to a total of 455 casualties. The Canadians counted over one hundred unburied dead Germans in the buildings and streets, confirming that many of the missing Germans were killed and that their recorded losses were conservative. A majority of the town was destroyed, and although 90 percent of Ortona’s civilian population had been forced to leave or had fled before the battle, those who stayed and tried to hide suffered greatly, with records showing that 1,314 were killed.

Lessons Learned

Any analysis of the lessons from the Battle of Ortona must be put into perspective. It occurred at a point during a world war when rural rather than urban warfare was the norm, and the Italian campaign had settled into a pattern: the Allies would advance, encounter a defensive line made up of natural obstacles, expend a great deal of resources breaching those obstacles, destroy the enemy positions there, and then advance once again to repeat the process. However, given Rome’s political and symbolic value, the Germans increased their defensive efforts when the risk that the city would fall to the Allies grew. Compared to the other defensive lines in southern Italy this meant making the Gustav Line’s defenses stronger and more challenging to overcome, including by anchoring it in urban areas.

At the strategic and theater levels, the Allies recognized that the Gustav Line was going to be stronger than previous defensive lines, but at the operational level British 8th Army intelligence—accustomed to rural or mountainous warfare—never recognized how the Germans would use a city to make it so. They assumed that the Arielli River just north of Ortona was part of the Gustav Line while Ortona and Villa Grande, another town just five kilometers to the southwest, never factored into the military intelligence analysis. The indicators may have been obscured by the pattern that had developed over the course of the Italian campaign, yet all of them were there. The enemy situation included a German parachute division being reinserted into the campaign. This was a unit that had no armor assets, but which had been put into a portion of the line where a complex urban town rested on a plateau. Therefore, in retrospect it is not a surprise that the Germans chose to stand and fight in Ortona. Thus, it is important that at the operational level patterns do not lead to dogmatic assumptions even though new factors have been introduced into the environment. Such operational intelligence assumptions should not be made today given the ubiquitous nature of urban warfare.

Most lessons learned from Ortona can be found at the tactical level. A clear lesson is the inherent advantages the urban environment gives the defender. If paratroopers, who were typically dismounted and did not have any tanks, were to defend against the Canadian advance, then it was logical for German military leaders to choose Ortona as the eastern anchor point of the Gustav Line rather than the Arielli River valley. Their four months of creative planning and preparation, combined with their tactics within the town, made it a strong defense against their attackers. Their use of rubbling—including destroying building faces to establish ambushes from the other side street, obstacle plans, engagement area development, and improvised building bombs—transformed a small urban area into a complex juggernaut that cost the Canadians time, resources, and soldiers to break through.

Conversely, the actions of the Canadians provide valuable lessons when approaching the difficult mission of attacking an urban area where defenders have had time to prepare their defenses. First, the Canadians demonstrated the value of combined arms formations in urban environments. Fortunately, much like the other Allied nations, the Canadians up to this point in the war had been practicing combined arms maneuver warfare throughout the rural environments in which they advanced. It is difficult to discern if the Canadians went into Ortona with infantry, tanks, engineers, and artillery working together because that was what they had become accustomed to doing up to that point or if they had made a conscious decision to ensure this occurred, but in the end, it was the correct employment of combined arms and proved that that is how urban battles are won. The close cooperation and symbiotic relationship between the dismounted infantry, engineers, armor, and fires from artillery and antitank guns—all supporting each other as they advanced through Ortona—was a model of combined arms teamwork in urban terrain.

Another tactical lesson, with operational-level planning implications, is highlighted by the large amount of ammunition used during the fighting. Operations in urban areas consume at least four times the amount of ammunition required in other environments. At Ortona, this high expenditure was due to the prepared defenses, buildings’ construction (which allowed them to act as naturally fortified strongpoints), and the close-quarters combat between both forces. Canadian soldiers, tanks, and antitank guns, and both Canadian and German artillery, required large amounts of ammunition, especially high-explosive rounds, to destroy strengthened buildings that housed enemy positions. Given these urban warfare requirements, operational headquarters must be prepared to forecast, move, supply, and resupply large quantities of ammunition.

The Canadians’ improvisation of weapons systems and explosives was another critical tactical lesson. Given that this was the first prolonged urban battle of the Italian campaign, nobody within the Allied camp had the tools and equipment that modern militaries can carry into urban combat today. Thus, the Canadians improvised with what they had: the equipment on their backs and the weapons systems they possessed. The Royal Canadian Artillery’s use of six-pounder and seventeen-pounder antitank guns to blow away and reduce the rubble piles and destroy German positions was one of the critical factors contributing to the Canadians’ success. The use of tanks in direct-fire support to breach building walls with a mixture of ammunition, to provide mobility and protection to advancing infantry and engineers, and to serve as sustainment vehicles highlights the essential requirement of tanks in high-intensity urban warfare.

Finally, the use of the mouseholing method was another tactic that heavily influenced the battle’s outcome. It enabled the Canadians to avoid having soldiers cut down on the open streets by remaining and moving inside buildings and allowed them to fight from the top down instead of from the bottom up. Although it was not invented by the Canadians—the method was actually already formalized in British doctrine and called “the vertical technique”—mouseholing was a common-sense tactic to apply to avoid casualties, advance under protective cover, and surprise the Germans by attacking from above.

Conclusion

Ortona was one of the first prolonged urban operations battles to be conducted by the Allies on the southern front of World War II. The battle provides an important example of large-scale combat operations between peer military forces that meet in urban terrain. Many of the tactics, techniques, and procedures applied by both the Germans and the Canadians and the lessons learned can still be applied today in urban operations.

Colonel (CA) John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He previously served as a fellow with the chief of staff of the Army’s Strategic Studies Group. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq.

Major Jayson Geroux is an infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment and currently with 1st Canadian Infantry Division Headquarters. He has been involved in urban operations training for two decades and is a passionate student of urban operations and urban warfare historian, having participated in, planned, executed, and intensively instructed on urban operations for the past seven years. He has served twenty-six years in the Canadian Armed Forces, which included operational tours to the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and Afghanistan.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization with which the authors are affiliated, including 1st Canadian Division Headquarters, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Canadian Department of National Defence.

Dear Professor Spencer,

My name is John Harrison I am with Rabdan Academy in the UAE where I am part of the Homeland Security and Intelligence program and helping with the new Zayed Military Univeristy. I would like to get some guidance on course development if I may.